Split Seconds of Magnificence Lydia Schouten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sean Landers

SEAN LANDERS 1962 Born in Palmer, MA, USA 1984 BFA, Philadelphia College of Art, Philadelphia, PA, USA 1986 MFA, Yale University School of Art, New Haven, CT, USA Lives and works in New York, NY, USA SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 2020 Vision, Petzel Gallery, New York, NY, USA (online presentation) Northeaster, greengrassi, London, UK Consortium Museum, Dijon, France (curated by Eric Troncy) 2019 Ben Brown Fine Arts, Hong Kong Galerie Rodolphe Janssen, Brussels, Belgium [Cat.] Curated by . Featuring Sean Landers, Petzel Bookstore, New York, NY, USA Sean Landers: Studio Films 90/95, Freehouse, London, UK (curated by Daren Flook) 2018 Petzel Gallery, New York, NY, USA [Cat.] 2016 Sean Landers: Small Brass Raffle Drum, Capitain Petzel, Berlin, Germany 2015 Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, Japan Galerie Rodolphe Janssen, Brussels, Belgium [Cat.] China Art Objects, Los Angeles, CA, USA 2014 Sean Landers: North American Mammals, Petzel Gallery, New York, NY, USA [Cat.] 2012 Galerie Rodolphe Janssen, Brussels, Belgium [Cat.] Longmore, Sorry We’re Closed, Brussels, Belgium greengrassi, London, UK 2011 Sean Landers: Around the World Alone, Friedrich Petzel Gallery, New York, NY, USA Sean Landers: A Midnight Modern Conversation, Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, NY [CAT.] 2010 Sean Landers: 1991-1994, Improbable History, Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, USA (curated by Laura Fried and Paul Ha) [Cat.] 2009 Sean Landers: Art, Life and God, Glenn Horowitz Bookseller, East Hampton, NY, USA (curated by Jeremy Sanders) greengrassi, London, UK Sean -

EWVA 4Th Full Proofxx.Pdf (9.446Mb)

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk Faculty of Arts and Humanities School of Art, Design and Architecture 2019-04 Ewva European Women's Video Art in The 70sand 80s http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/16391 JOHN LIBBEY PUBLISHING All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. EWVA EuropeanPROOF Women’s Video Art in the 70s and 80s do not distribute PROOF do not distribute Cover image: Lydia Schouten, The lone ranger, lost in the jungle of erotic desire, 1981, still from video. Courtesy of the artist. EWVA European Women’s PROOF Video Art in the 70s and 80s Edited by do Laura Leuzzi, Elaine Shemiltnot and Stephen Partridge Proofreading and copyediting by Laura Leuzzi and Alexandra Ross Photo editing by Laura Leuzzi anddistribute Adam Lockhart EWVA | European Women's Video Art in the 70s and 80s iv British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data EWVA European Women’s Video Art in the 70s and 80s A catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 9780 86196 734 6 (Hardback) PROOF do not distribute Published by John Libbey Publishing Ltd, 205 Crescent Road, East Barnet, Herts EN4 8SB, United Kingdom e-mail: [email protected]; web site: www.johnlibbey.com Distributed worldwide by Indiana University Press, Herman B Wells Library – 350, 1320 E. -

From Squatting to Tactical Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2019 Between the Cracks: From Squatting to Tactical Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993 Amanda S. Wasielewski The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3125 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] BETWEEN THE CRACKS: FROM SQUATTING TO TACTICAL MEDIA ART IN THE NETHERLANDS, 1979–1993 by AMANDA WASIELEWSKI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partiaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 AMANDA WASIELEWSKI ALL Rights Reserved ii Between the Cracks: From Squatting to TacticaL Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993 by Amanda WasieLewski This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy. Date David JoseLit Chair of Examining Committee Date RacheL Kousser Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Marta Gutman Lev Manovich Marga van MecheLen THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Between the Cracks: From Squatting to TacticaL Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993 by Amanda WasieLewski Advisor: David JoseLit In the early 1980s, Amsterdam was a battLeground. During this time, conflicts between squatters, property owners, and the police frequentLy escaLated into fulL-scaLe riots. -

EWVA European Women's Video

EWVA European Women’s Video Art Interview with Lydia Schouten Interview by Dr Laura Leuzzi, November 2015 LL: When did you first start using video? What equipment did you use at the time? LS: I started using video the first time in 1977 as part of the performance: Love is every girl’s dream. LL: In 1977 you started incorporating video and video installations in your performances. Could you talk to us about how you developed the performance Love is every girls dream? LS: I wanted to make a performance about dreaming, where I would lie in a circle of flour, broken mirrors and brick stones. On both sides would be a monitor. On one monitor I was putting make-up on my face whilst looking in a broken mirror. On the other monitor I was building the circle with flour, stones and mirrors. For me it had to do with dreaming about a career without being able to brake through the conventions of life at that time. I did the performance at the Stedelijk Museum Gouda during the opening of an exhibition about ‘Dreams’. During the whole opening I was asleep in my circle with the two videos playing. LL: Why was video as a medium particularly attractive for you at the time? LS: I loved using video because it was still so experimental. Not many people had used it at the time and I felt free to do whatever I wanted to do with it. LL: In several early videos you addressed relevant feminist themes. For example in Rome is bleeding (1982) and Covered in cold sweat (1983) you undermine the stereotypes in the relationship and role of men and women and challenge women to rebel again the dominance of men over women imposed by patriarchal culture and society. -

New Media Art. Uva Contemporary Art Conservation Student Symposium

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Re: New Media Art. Technology-based Art Conservation 2018-2019 Contemporary Art Conservation Student Symposium : 7 October 2019, Ateliergebouw, Amsterdam Stigter, S.; Snijders, E.; Jansen, E. DOI 10.21942/uva.9917207.v1 Publication date 2019 Document Version Final published version License CC BY Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Stigter, S., Snijders, E., & Jansen, E. (Eds.) (2019). Re: New Media Art. Technology-based Art Conservation: 2018-2019 Contemporary Art Conservation Student Symposium : 7 October 2019, Ateliergebouw, Amsterdam. University of Amsterdam, Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage. https://doi.org/10.21942/uva.9917207.v1 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided -

FEMINIST AVANT-GARDE of the 1970S

FEMINIST AVANT-GARDE OF THE 1970s Works from the Verbund Collection 7 Oct 2016—15 Jan 2017 Feminist Avant–Garde of the 1970s: Works from the SAMMLUNG VERBUND Collection, Vienna, comprises over 200 major works by forty-eight international artists. Focusing on photography, collage, performance, film and video work produced throughout the 1970s, the exhibition reflects a moment when protests related to emancipation, gender equality and civil rights became part of public discourse. Through radical, poetic, ironic and often provocative investigations, women artists were galvanised to use their work as a further means of engagement – questioning feminine identities, gender roles and sexual politics through new modes of expression. This exhibition highlights the groundbreaking practices that shaped the feminist art movement and provides a timely reminder of the wider impact of a generation of artists. Curated by Gabriele Schor, Director of the SAMMLUNG VERBUND, and Anna Dannemann, Curator at The Photographers’ Gallery. Elephants in the Room, a day of discussion and events inspired by the exhibition, will take place on Saturday 19 November, 10.00–20.00. Tickets £15/£12 available from www.tpg.org.uk HELENA ALMEIDA ELEANOR ANTIN b. 1934 in Lisbon, Portugal | lives and works in Lisbon, b. 1935 in New York, USA | lives and works in California, Portugal USA Helena Almeida’s work has always challenged traditional I am interested in defining the limits of myself. I consider the values in art. Her earliest work subverted classical usual aids to self-definition—sex, age, talent, time, and space— painting through its ambiguous compositions, combining as tyrannical limitations upon my freedom of choice. -

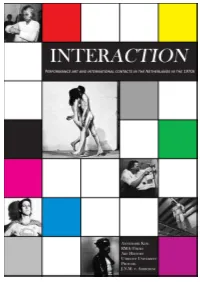

INTERACTION Thesis Annemarie Kok.Pdf

INTERACTION PERFORMANCE ART AND INTERNATIONAL CONTACTS IN THE NETHERLANDS IN THE 1970S Research Master Thesis Art History of the Low Countries in its European Context Utrecht University Student: Annemarie Kok Number: 0210137 Supervisor: Prof.dr. J.N.M. van Adrichem Date: November 2009 Table of contents Preface 5 Introduction 7 1. Performance art in the Netherlands 13 1.1.Performance art. An international ‘definition’ 13 1.2.Rise and scope of performance art in the Netherlands 17 1.3.Performance artists in the Netherlands 19 1.4.Places to perform 26 2. A characterization of performance art in the Netherlands in the 1970s 33 2.1.Covering tendencies with relation to content 33 2.2.Covering tendencies with relation to form 39 2.2.1. Formal elements 39 2.2.2. Formal arrangement 43 2.3.Covering tendencies with relation to the attitude of the performance artist 46 2.4.Final observations 48 3. Performance art in the Netherlands in an international context 51 3.1.Interfaces with European performance art 51 3.2.Interfaces with American performance art 57 3.3.Final observations 62 4. Structural relation networks 65 4.1.The circle around Ben d’Armagnac 65 4.2.The circle around the Latin American artists in the Netherlands 68 4.3.Two circles, two categories 70 4.4.The circle around De Appel and Wies Smals 71 4.5.The circle around Agora Studio 72 4.6.The circle around Corps de Garde and Leendert van Lagestein 73 4.7.Structural relation networks: interaction and intermixture 75 5. -

Sean Landers

SEAN LANDERS 1962 Born in Palmer, MA, USA 1986 MFA, Yale University School of Art, New Haven, CT, USA 1984 BFA, Philadelphia College of Art, Philadelphia, PA, USA Lives and works in New York, NY, USA SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Petzel Gallery, New York, NY, USA [Cat.] 2016 Sean Landers: Small Brass Raffle Drum, Capitain Petzel, Berlin, Germany 2015 Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, Japan Galerie Rodolphe Janssen, Brussels, Belgium [Cat.] China Art Objects, Los Angeles, CA, USA 2014 Sean Landers: North American Mammals, Petzel Gallery, New York, NY, USA [Cat.] 2012 Galerie Rodolphe Janssen, Brussels, Belgium [Cat.] Longmore, Sorry We’re Closed, Brussels, Belgium greengrassi, London, UK 2011 Sean Landers: Around the World Alone, Friedrich Petzel Gallery, New York, NY, USA Sean Landers: A Midnight Modern Conversation, Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, NY [CAT.] 2010 Sean Landers: 1991–1994, Improbable History, Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, USA (curated by Laura Fried and Paul Ha) [Cat.] 2009 Sean Landers: Art, Life and God, Glenn Horowitz Bookseller, East Hampton, NY, USA (curated by Jeremy Sanders) [publication] greengrassi, London, UK Sean Landers: Sadness Racket, Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, Japan 2008 Sean Landers: Set of Twelve, Friedrich Petzel Gallery, New York, NY, USA Sean Landers: Chagrins of the New Episteme, Galerie Giti Nourbakhsch, Berlin, Germany 2007 China Art Objects, Los Angeles, CA, USA Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York, NY, USA 2006 Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, Japan greengrassi, London, UK 2005 Galerie Giti Nourbakhsch, -

Sean Landers

SEAN LANDERS Born 1962, Palmer, MA EDUCATION 1986 MFA, Yale University School of Art, New Haven, CT 1984 BFA, Philadelphia College of Art, Philadelphia, PA Lives and works in New York, NY SOLO AND TWO-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2020 Le Consortium, Dijon, France Northeaster, greengrassi, London, UK Sean Landers and Alessandro Pessoli, greengrassi, London, UK 2019 Sean Landers: Studio Films 90/95, Freehouse, London, United Kingdom 2018 Petzel Gallery, New York, NY 2016 Small Brass Raffle Drum, Capitain Petzel, Berlin, Germany 2015 Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, Japan Galerie Rodolphe Janssen, Brussels, Belgium China Art Objects, Los Angeles, CA 2014 Sean Landers: North American Mammals, Petzel Gallery, New York, NY, 2012 Galerie Rodolphe Janssen, Brussels, Belgium Longmore, Sorry We’re Closed, Brussels, Belgium greengrassi, London, UK 2011 Sean Landers: Around the World Alone, Friedrich Petzel Gallery, New York, NY Sean Landers: A Midnight Modern Conversation, Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, NY 2010 Sean Landers: 1991–1994, Improbable History, Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, (curated by Laura Fried and Paul Ha) 2009 Sean Landers: Art, Life and God, Glenn Horowitz Bookseller, East Hampton, NY (curated by Jeremy Sanders) greengrassi, London, UK Sean Landers: Sadness Racket, Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, Japan 2008 Sean Landers: “Set of Twelve”, Friedrich Petzel Gallery, New York, NY Sean Landers: Chagrins of the New Episteme, Galerie Giti Nourbakhsch, Berlin, Germany 2007 China Art Objects, Los Angeles, CA Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York, -

Programme 2Nd European Expert Conference Hamburg, Germany - September 1999

"PYRAMID OR PILLARS” UNVEILING THE STATUS OF WOMEN IN ARTS AND MEDIA PROFESSIONS IN EUROPE" CONFERENCE PROGRAMME 2ND EUROPEAN EXPERT CONFERENCE HAMBURG, GERMANY - SEPTEMBER 1999 ERICARTS Dahlmannstr. 26, D - 53113 Bonn Tel. (+49-228) 2420996/7 * Fax 241318 e-mail: [email protected] Pyramid or Pillars 2nd European Expert Conference: Women in Arts and Media Professions – European Comparisons 30 September to 2 October 1999 Hochschule für Musik und Theatre/Literaturhaus, Hamburg Conference Programme Thursday 30th September: Literaturhaus, Hamburg 19h30-21h45: Welcome and Opening Statements Ursula Keller, Director Literaturhaus, Hamburg Andreas Wiesand, ERICarts/ZfKf, Bonn *Christine Bergmann, Federal Minister for Youth, Seniors and Women Opening Performances/Lecture Reading/Lecture by Elisabeth Bronfen, Zurich Sound Poetry by Isabella Beumer, Hamburg Felicja Bozyszkowska, Warsaw 21h45: Reception Friday 1 October: Hochschule für Musik und Theater, Hamburg 9h30 to 13h30: Women in Arts and Media Professions: European Comparisons Opening Statement: Ritva Mitchell – Head of Research, Arts Council of Finland/ERICarts Many scholars including Germaine Greer and Pierre Bordieu have observed that for all the legal, political and social progress made in the last century, not much has changed in the area of equality and in some cases has worked against women. Some results from the ERICarts study for the European Commission go beyond these observations and indicate that parts of the cultural sector are being "feminised" during a period when the public -

The Academy of the Senses

The Academy of the Senses SYNESTHETICS IN SCIENCE, ART, AND EDUCATION FRANS EVERS The Academy of the Senses SYNESTHETICS IN SCIENCE, ART, AND EDUCATION FRANS EVERS Compiled and edited by VINCENT W.J. VAN GERVEN OEI ArtScience Interfaculty Press SYN·ES·THET·ICS n. 1. (used with a sing. verb) a. The branch of esthetics (Eng. aesthetics) dealing with joint esthetics, the artistic effects resulting from bringing together esthetics from different disciplines in one work of art, often as a consequence of the use of new technologies b. In Kantian philosophy esthetics is the branch of metaphysics concerned with the laws of perception. Synesthesia “is a term that refers to the transposition of sensory images or sensory attributes from one modality to the other”(Marks). The word synesthesia is composed of two elements: syn (with, together, alike, similarity) and aesthesia (to feel, per- ceive). In analogy we may describe synesthetics as “joint esthetics” c. Synesthetics, synesthetic art, verbal synesthesia, and sensory synesthesia are all manifestations of a guiding perceptual principle: “the unity of the senses.” According to ethnomusicologist Erich M. von Hornbostel this interrelatedness of the senses can be observed in daily life situations, in new media such as film as well as in the unity of the arts which was given from the origin (masked dance) 2. (used with a sing. verb) The study of the esthetics of visual music (Castel), Gesamtkunst (Wagner, Kandinsky), the art of relationships (Mondrian, Moholy-Nagy), synaesthetics and kinaesthetics: the way of all experience (Youngblood) as well as more recent forms of genera- tive art, interactive art and mediated environments 3. -

The SAMMLUNG VERBUND Collection, Vienna

The SAMMLUNG VERBUND Collection, Vienna The SAMMLUNG VERBUND collection was founded in 2004 by VERBUND. It aspires to uniquely position itself, both nationally and internationally, in the area of contemporary art and to create an unmistakable identity. Maxim: The collection’s maxim is „Depth rather than breadth“. Spotlighting whole groups of works allows a deeper level of engagement with an artist‘s particular period of artistic creativity. Artists: By 2017, the collection had acquired 1.000 works by a total of 138 artists. Director: Gabriele Schor, The SAMMLUNG VERBUND Collection, Vienna International Board of Trustess: Jessica Morgan, Dia Art Foundation, New York Camille Morineau, Monnaie de Paris, Paris Current exhibition abroad Feminist Avant-Garde of the 1970s from the SAMMLUNG VERBUND Collection, Vienna Stavanger Art Museum 16. June - 14. October 2018 curated by Gabriele Schor With an exhibition of over 200 works from the SAMMLUNG VERBUND collection, the Kunstmuseum Stavanger presents one of the most important phenomena of art history in the 1970s - the emancipation of women artists who redefined their own collectively self-determined image of women in a male-dominated art world. True to the slogan „the private is political“, these artists reflected stereotypical social expectations in their work. The exhibition is divided into five sections: reduction to mother, housewife and wife, role-plays, normativity of beauty, female sexuality and the breaking out of social constraints. Many of the artists represented here moved away from the male-dominated genre of painting and turned to the media of photography, video, film and performance. Founding director Gabriele Schor coined the term feminist avant-garde to underscore its importance for this movement.