044-Santa Maria in Cosmedin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spirit of Rome, by Vernon Lee 1

The Spirit of Rome, by Vernon Lee 1 The Spirit of Rome, by Vernon Lee The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Spirit of Rome, by Vernon Lee This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Spirit of Rome Author: Vernon Lee Release Date: January 22, 2009 [EBook #27873] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 The Spirit of Rome, by Vernon Lee 2 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SPIRIT OF ROME *** Produced by Delphine Lettau & the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries. THE SPIRIT OF ROME BY VERNON LEE. CONTENTS. Explanatory and Apologetic I. First Return to Rome II. A Pontifical Mass at the Sixtine Chapel III. Second Return to Rome IV. Ara Coeli V. Villa Cæsia VI. The Pantheon VII. By the Cemetery SPRING 1895. I. Villa Livia II. Colonna Gallery III. San Saba IV. S. Paolo Fuori V. Pineta Torlonia SPRING 1897. I. Return at Midnight II. Villa Madama III. From Valmontone to Olevano IV. From Olevano to Subiaco V. Acqua Marcia VI. The Sacra Speco VII. The Valley of the Anio VIII. Vicovaro IX. Tor Pignattara X. Villa Adriana XI. S. Lorenzo Fuori XII. On the Alban Hills XIII. Maundy Thursday XIV. Good Friday XV. -

The Spolia Churches of Rome

The Spolia Churches of Rome Recycling Antiquity in the Middle Ages ISBN: 9788771242102 (pb) by Maria Fabricius Hansen PRICE: DESCRIPTION: $29.95 (pb) A particularly robust approach to Rome's antique past was taken in the Middle Ages, spanning from the Late Antiquity in the fourth century, until roughly the thirteenth century AD. The Spolia Churches PUBLICATION DATE: of Rome looks at how the church-builders treated the architecture of ancient Rome like a quarry full 30 June 2015 (pb) of prefabricated material and examines the cultural, economic and political structure of the church and how this influenced the building's design. It is this trend of putting old buildings to new uses BINDING: which presents an array of different forms of architecture and design within modern day Rome. Paperback This book is both an introduction to the spolia churches of medieval Rome, and a guide to eleven selected churches. SIZE: 4 x8 TABLE OF CONTENTS: Recycling Antiquity Introduction Historical background Spolia in the Early Christian basilica PAGES: Principles for the distribution of spolia Building on the past Materials and meaning Old and new side 255 by side Selected spolia churches The Lateran Baptistery Sant'Agnese San Clemente Santa Costanza San Giorgio in Velabro San Lorenzo fuori le Mura Santa Maria in Cosmedin Santa Maria in ILLUSTRATIONS: Trastevere San Nicola in Carcere Santa Sabina Santo Stefano Rotondo Practical Information Other 120 illus. noteworthy spolia churches Timeline Popes Glossary Materials Bibliography Index PUBLISHER: CONTRIBUTORS BIOGRAPHIES: Aarhus University Press Maria Fabricius Hansen is an art historian and associate professor at the University of Copenhagen. -

The Life of Saint Bernard De Clairvaux

The Life of Saint Bernard de Clairvaux Born in 1090, at Fontaines, near Dijon, France; died at Clairvaux, 21 August, 1153. His parents were Tescelin, lord of Fontaines, and Aleth of Montbard, both belonging to the highest nobility of Burgundy. Bernard, the third of a family of seven children, six of whom were sons, was educated with particular care, because, while yet unborn, a devout man had foretold his great destiny. At the age of nine years, Bernard was sent to a much renowned school at Chatillon-sur-Seine, kept by the secular canons of Saint-Vorles. He had a great taste for literature and devoted himself for some time to poetry. His success in his studies won the admiration of his masters, and his growth in virtue was no less marked. Bernard's great desire was to excel in literature in order to take up the study of Sacred Scripture, which later on became, as it were, his own tongue. "Piety was his all," says Bossuet. He had a special devotion to the Blessed Virgin, and there is no one who speaks more sublimely of the Queen of Heaven. Bernard was scarcely nineteen years of age when his mother died. During his youth, he did not escape trying temptations, but his virtue triumphed over them, in many instances in a heroic manner, and from this time he thought of retiring from the world and living a life of solitude and prayer. St. Robert, Abbot of Molesmes, had founded, in 1098, the monastery of Cîteaux, about four leagues from Dijon, with the purpose of restoring the Rule of St. -

LIST of PLATES 1. Aula Palatina, Trier, External and Internal View

vii LIST OF PLATES 1. Aula Palatina, Trier, external and internal view. Photo: J. Hawkes. 2. Basilica Nova, Rome, present view and reconstruction. Photo: author; reconstruction: J. Hawkes. 3. Fragments of the monumental statue of Constantine, Rome. Photo: J. Hawkes. 4. Constantine Arch, Rome. Photo: author. 5. Septimius Severus Arch, Rome. Photo: from Wikimedia Commons. 6. Constantine Arch, re-used Hadrianic tondoes. Photo: author. 7. Map of Constantinian foundations. Photo: from LEHMANN, edited by the author. 8. Plan of St Peter’s Basilica and of Lateran Basilica. Photo: from BRANDENBURG. 9. Plan of Circus Basilicas. Photo: from BRANDENBURG. 10. Santa Costanza, Rome, plan and aerial view. Photo: plan from BRANDENBURG; aerial view: J. Hawkes. 11. Examples of Roman Mausolea. a) Mausoleum of Cecilia Metella, Rome. Photo: author. b) mausoleum of Diocletian, Split. Photo: J. Hawkes. c) Mausoleum of Hadrian, Rome. Photo: author. 12. Santa Costanza, Rome, vault mosaics, cross and lozenges. Photo: author. 13. Santa Costanza, Rome, vault mosaic, vintage scene. Photo: author. 14. Santa Costanza, Rome, vault mosaics, Traditio Legis. Photo: author. 15. Santa Costanza, Rome, vault mosaics, Traditio Pacis. Photo: author. 16. St Peter’s Basilica, Rome, reconstruction of apse mosaic. Photo: from Christiana Loca. 17. San Paolo fuori le mura, Rome, apse mosaic. Photo: from BRANDENBURG. 18. Lateran Basilica, Rome, apse mosaic. Photo: from Wikimedia Commons. 19. Santa Pudenziana, Rome, apse mosaic. Photo: author. 20. Reconstruction of the fastigium at the Lateran Basilica. Photo: from TEASDALE SMITH. 21. Santa Sabina, Rome. Photo: author. 22. Plan of titulus Pammachii (SS Giovanni e Paolo), Rome. Photo: from DI GIACOMO. -

(Michelle-Erhardts-Imac's Conflicted Copy 2014-06-24).Pages

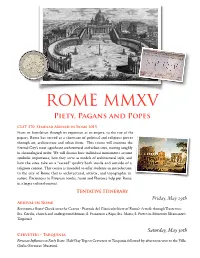

ROME MMXV Piety, Pagans and Popes CLST 370: Seminar Abroad in Rome 2015 From its foundation through its expansion as an empire, to the rise of the papacy, Rome has served as a showcase of political and religious power through art, architecture and urban form. This course will examine the Eternal City’s most significant architectural and urban sites, moving roughly in chronological order. We will discuss how individual monuments assume symbolic importance, how they serve as models of architectural style, and how the sites take on a “sacred” quality both inside and outside of a religious context. This course is intended to offer students an introduction to the city of Rome that is architectural, artistic, and topographic in nature. Excursions to Etruscan tombs, Assisi and Florence help put Rome in a larger cultural context. " Tentative Itinerary" Friday, May 29th! Arrival in Rome Benvenuto a Roma! Check into the Centro - Piazzale del Gianicolo (view of Rome) -A walk through Trastevere: Sta. Cecilia, church and underground domus; S. Francesco a Ripa; Sta. Maria; S. Pietro in Montorio (Bramante’s Tempietto)." Saturday, May 30th! Cerveteri - Tarquinia Etruscan Influences on Early Rome. Half-Day Trip to Cerveteri or Tarquinia followed by afternoon visit to the Villa " Giulia (Etruscan Museum). ! Sunday, May 31st! Circus Flaminius Foundations of Early Rome, Military Conquest and Urban Development. Isola Tiberina (cult of Asclepius/Aesculapius) - Santa Maria in Cosmedin: Ara Maxima Herculis - Forum Boarium: Temple of Hercules Victor and Temple of Portunus - San Omobono: Temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta - San Nicola in Carcere - Triumphal Way Arcades, Temple of Apollo Sosianus, Porticus Octaviae, Theatre of Marcellus. -

Chiese Cattoliche Data Di Aggiornamento: 30/09/21 22:27

Chiese cattoliche Data di aggiornamento: 30/09/21 22:27 1. Abbazia delle Tre Fontane 14. Basilica di San Sebastiano fuori le Mura Indirizzo: Via Acque Salvie, 1 Indirizzo: Via Appia Antica, 136 Telefono: 06 5401655 Telefono: 06 7808847 Sito web: www.abbaziatrefontane.it Sito web: www.sansebastianofuorilemura.org/la-parrocchia 2. Basilica dei Santi XII Apostoli 15. Basilica di Sant'Antonio al Laterano Indirizzo: Piazza dei Santi Apostoli, 51 Indirizzo: Via Merulana, 124 Telefono: 06 699571 Telefono: 06 70373416 - 06 70373420 Sito web: www.basilica-santantonio-roma.org/ 3. Basilica dei Ss. Giovanni e Paolo al Celio Indirizzo: Piazza dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo, 13 16. Basilica di Santa Cecilia in Trastevere Telefono: 06 7005745 - 06 772711 Indirizzo: Piazza di Santa Cecilia, 22 Telefono: 06 5899289 4. Basilica dei Ss. Pietro e Paolo all'EUR Sito web: www.benedettinesantacecilia.it Indirizzo: Piazzale Santi Pietro e Paolo, 8 Telefono: 06 5926166 17. Basilica di Santa Croce in Gerusalemme Sito web: www.santipietroepaoloroma.it Indirizzo: Piazza di Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, 12 Telefono: 06 70613053 5. Basilica di San Crisogono Sito web: www.santacroceroma.it Indirizzo: Piazza Sidney Sonnino, 44 Telefono: 06 5810076 - 06 5818225 18. Basilica di Santa Maria in Aracoeli Indirizzo: Scala dell'Arce Capitolina, 14 - Piazza del Campidoglio 6. Basilica di San Giovanni a Porta Latina Telefono: 06 69763837 - 39 Indirizzo: Via di Porta Latina, 17 Telefono: 06 70475938 19. Basilica di Santa Maria in Cosmedin Sito web: www.sangiovanniaportalatina.it/Index.htm Indirizzo: Piazza della Bocca della Verità, 18 Telefono: 06 6787759 7. Basilica di San Giovanni Bosco Sito web: www.cosmedin.org Indirizzo: Viale dei Salesiani, 9 Telefono: 06 710401235 20. -

Santa Maria in Trastevere

A Building’s Images: Santa Maria in Trastevere Dale Kinney Images If only because it has an inside and an outside, a building cannot be grasped in a single view. To see it as a whole one must assemble images: the sensory impressions of a beholder moving through or around it (perceptual images), the objectified views of painters and photographers (pictorial images), the analytical graphics of architects (analytical images), and now, virtual simulacra derived from laser scans, photogrammetry, and other means of digital measurement and representation. These empirical images can be overlaid by abstract or symbolic ones: themes or metaphors imagined by the architect or patron (intended images); the image projected by contingent factors such as age, condition, and location (projected images); the collective image generated by the interaction of the building’s appearance with the norms and expectations of its users and beholders; the individual (but also collectively conditioned) “phenomenological” images posited by Gaston Bachelard (psychological images), and many more.1 In short, the topic of a building’s images is one of almost unlimited complexity, not to be encompassed in a brief essay. By way of confining it I will restrict my treatment to a single example: Santa Maria in Trastevere, a twelfth-century church basilica on the right bank of the Tiber River in Rome. I will focus on its intended, projected, and collective images in two key eras of its existence. Pictorial images, including those surviving inside the basilica and the representations of it by artist- architects in the 19th century, are considered in relation to the ephemeral images that are my principal subject and their role in constituting communal identities. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

Case: 20-56156, 06/21/2021, ID: 12149429, DktEntry: 33, Page 1 of 35 No. 20-56156 United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit JOANNA MAXON et al., Plaintiffs/Appellants, v. FULLER THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, et al., Defendants/Appellees. Appeal from the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California | No. 2:19-cv-09969 (Hon. Consuelo B. Marshall) ____________________________________________ BRIEF OF PROFESSORS ELIZABETH A. CLARK, ROBERT F. COCHRAN, TERESA S. COLLETT, CARL H. ESBECK, DAVID F. FORTE, RICHARD W. GARNETT, DOUGLAS LAYCOCK, MICHAEL P. MORELAND, AND ROBERT J. PUSHAW AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES ____________________________________________ C. Boyden Gray Jonathan Berry Michael Buschbacher* T. Elliot Gaiser BOYDEN GRAY & ASSOCIATES 801 17th Street NW, Suite 350 Washington, DC 20006 202-955-0620 [email protected] * Counsel of Record (application for admission pending) Case: 20-56156, 06/21/2021, ID: 12149429, DktEntry: 33, Page 2 of 35 CERTIFICATE OF INTEREST Pursuant to Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 26.1, counsel for amici hereby certifies that amici are not corporations, and that no disclosure statement is therefore required. See Fed. R. App. P. 29(a)(4)(A). Dated: June 21, 2021 s/ Michael Buschbacher i Case: 20-56156, 06/21/2021, ID: 12149429, DktEntry: 33, Page 3 of 35 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................ ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ..................................................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ............................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ................... 2 ARGUMENT ............................................................................................... 6 I. THE PRINCIPLE OF CHURCH AUTONOMY IS DEEPLY ROOTED IN THE ANGLO-AMERICAN LEGAL TRADITION. ................................................ 6 II. THE FIRST AMENDMENT PROHIBITS GOVERNMENT INTRUSION INTO THE TRAINING OF SEMINARY STUDENTS. -

The Małopolska Way of St James (Sandomierz–Więcławice Stare– Cracow–Szczyrk) Guide Book

THE BROTHERHOOD OF ST JAMES IN WIĘCŁAWICE STARE THE MAŁOPOLSKA WAY OF ST JAMES (SANDOMIERZ–WIĘCŁAWICE STARE– CRACOW–SZCZYRK) GUIDE BOOK Kazimiera Orzechowska-Kowalska Franciszek Mróz Cracow 2016 1 The founding of the pilgrimage centre in Santiago de Compostela ‘The Lord had said to Abram, “Go from your country, your people and your father’s household to the land I will show you”’ (Gen 12:1). And just like Abraham, every Christian who is a guest in this land journeys throughout his life towards God in ‘Heavenly Jerusalem’. The tradition of going on pilgrimages is part of a European cultural heritage inseparably connected with the Christian religion and particular holy places: Jerusalem, Rome, and Santiago de Compostela, where the relics of St James the Greater are worshipped. The Way of St James began almost two thousand years ago on the banks of the Sea of Galilee (Lake Tiberias). As Jesus was walking beside the Sea of Galilee, he saw two brothers, Simon called Peter and his brother Andrew. They were casting a net into the lake, for they were fishermen. ‘Come, follow me,’ Jesus said, ‘and I will send you out to fish for people’. At once they left their nets and followed him. Going on from there, he saw two other brothers, James son of Zebedee and his brother John. They were in a boat with their father Zebedee, preparing their nets. Jesus called them, and immediately they left the boat and their father and followed him. (Matthew 4:18‒22) Mortal St James The painting in Basilica in Pelplin 2 The path of James the Apostle with Jesus began at that point. -

Daily Saints – 1 March St. David of Wales Born: 500 AD, Caerfai Bay

Daily Saints – 1 March St. David of Wales Born: 500 AD, Caerfai Bay, United Kingdom, Died: March 1, 589 AD, St David’s, United Kingdom, Feast: 1 March, Canonized: 1123, Rome, Holy Roman Empire (officially recognized) by Pope Callixtus II, Venerated in Roman Catholic Church; Eastern Orthodox Church; Anglican Communion, Attributes: Bishop with a dove, usually on his shoulder, sometimes standing; on a raised hillock Among Welsh Catholics, as well as those in England, March 1 is the liturgical celebration of Saint David of Wales. St. David is the patron of the Welsh people, remembered as a missionary bishop and the founder of many monasteries during the sixth century. David was a popular namesake for churches in Wales before the Anglican schism, and his feast day is still an important religious and civic observance. Although Pope Benedict XVI did not visit Wales during his 2010 trip to the U.K., he blessed a mosaic icon of its patron, and delivered remarks praising St. David as “one of the great saints of the sixth century, that golden age of saints and missionaries in these isles, and...thus a founder of the Christian culture which lies at the root of modern Europe.” In his comments, Pope Benedict recalled the saint's dying words to his monastic brethren: "Be joyful, keep the faith, and do the little things." He urged that St. David's message, "in all its simplicity and richness, continue to resound in Wales today, drawing the hearts of its people to a renewed love for Christ and his Church." From a purely historical standpoint, little is known of David’s life, with the earliest biography dating from centuries after his time. -

Summer-Fall Newsletter

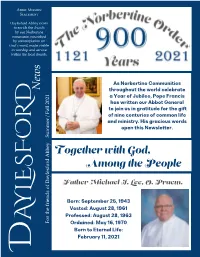

Abbey Mission Statement Daylesford Abbey exists to enrich the church by our Norbertine communio, nourished by contemplation on God’s word, made visible in worship and service within the local church. As Norbertine Communities News throughout the world celebrate a Year of Jubilee, Pope Francis D has written our Abbot General to join us in gratitude for the gift of nine centuries of common life and ministry. His gracious words open this Newsletter. Together with God, Among the People Father Michael J. Lee, O. Praem. Born: September 25, 1943 Vested: August 28, 1961 Professed: August 28, 1963 AYLESFOR For the friends of Daylesford Abbey Summer / Fall 2021 Ordained: May 16, 1970 Born to Eternal Life: February 11, 2021 D Contents 1. A Letter from the Abbot A Letter From the Abbot by Abbot Domenic A. Rossi, O. Praem. Words from Pope Francis 2. Words from Pope Francis For a number of years now, the Abbey has had two fig trees nestled in an 4. In Memoriam: outside area of one of our gardens, Fr. Michael Lee, O. Praem. well protected from winter winds. by Joseph McLaughlin, O. Praem. We would typically get at most, a few 5. Norbertine Farewell dozen figs and only at the very end to Saint Gabriel Parish of the summer. This year, however, was very different. by Francis X. Cortese, O. Praem. On just one of the fig trees, as soon as the leaves were starting to appear this spring, there also appeared dozens 7. Development Corner and dozens of figs(I counted 72). Moreover, the fruit were by John J. -

Santa Maria in Cosmedin

La basilica di Santa Maria in Cosmedin è un luogo di culto cattolico di Roma, situato in piazza della Bocca della Verità, nel rione Ripa; officiata dalla Chiesa cattolica greco-melchita, ha la dignità di basilica minore e su di essa insiste l'omonima diaconia. La basilica, frutto dell'ampliamento sotto papa Adriano I (772-790) di un precedente luogo di culto cristiano attestato fin dal VI secolo, fu oggetto di un importante rifacimento nel 1123 ed è attualmente uno dei rari esempi di architet- tura sacra del XII secolo a Roma; è nota per la presenza nel nartece della Bocca della Verità. Un po’di storia Il sito su cui sorge la basilica di Santa Maria in Cosmedin, in epoca romana si trovava al margine sud-orientale del Foro Boario, prossimo al fium Tevere e a Circo Massimo. In quest'area trovava luogo l'Ara massima di Ercole invitto, edificata secondo la tradizione da Evandro dopo che Ercole ebbe ucciso il gigante Caco, e che assunse la sua conformazione definitiva con una ricostruzione nel II secolo a.C. Alla metà del IV secolo d.C. venne edificata immediatamente ad ovest dell'Ara massima e ad essa adiacente un'aula porticata, posta su un podio e delimitata da arcate poggianti su colonne; essa era molto probabilmente priva di copertura in quanto sarebbe risultata molto costosa a causa della notevole altezza delle pareti (18 metri), nonché soggetta agli incendi che avrebbe potuto appiccare il fuoco dei sacrifici del santuario attiguo; secondo altri studi, invece, la presenza di stucchi al suo interno avrebbe necessariamente richiesto la presenza di un tetto.