Signatures, Spring/ Summer 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hotel Intercontinental V Praze Historie | Urbanismus | Architektura | Architektura Historie |Urbanismus V Praze Intercontinental Hotel Kateřina Houšková Akol

HOTEL INTERCONTINENTAL Historie | urbanismus architektura Historie V PRAZE Historie | urbanismus | architektura Kateřina Houšková a kol. ISBN 978-80-7480-129-7 HOTEL INTERCONTINENTAL V PRAZE INTERCONTINENTAL HOTEL HOTEL INTERCONTINENTAL V PRAZE Historie | urbanismus | architektura Kateřina Houšková a kol. HOTEL INTERCONTINENTAL V PRAZE Historie | urbanismus | architektura Publikace vznikla v rámci výzkumného projektu „Analýza a prezentace hodnot moderní architektury 60. a 70. let 20. století jako součásti národní a kulturní identity ČR“, číslo DG16P02R007, který je realizován díky finanční podpoře Ministerstva kultury v rámci Programu aplikovaného výzkumu a vývoje národní a kulturní identity (NAKI). Poděkování autorů Velké poděkování a úctu si bezvýhradně zaslouží všichni lidé, s nimiž jsme jednali, konzultovali či od nich nebo díky nim získávali veškeré archivní a soukromé materiály i ústní svědectví. Přednostně bychom chtěli zmínit zaměstnance IHC, zejména Kristýnu Hájkovou (PR & Marketing Manager), dále spoluautory, pamětníky a dědice, se kterými jsme byli opakovaně v kontaktu a kteří nás nezištně a ochotně zásobili materiály i pomocí, Zdenku Novákovou, Magdalenu Cubrovou, Oldřicha Novotného, Zdeňka Rothbauera, Kryštofa Hejného a Tomáše Hlavičku. Na tomto místě bychom chtěli zdůraznit vstřícnost zaměstnanců Institutu plánování a rozvoje hlavního města Prahy, zejména Martiny Koukalové z archivu IPR, a dále Kláry Jeništové, kurátorky sbírky architektury Městského muzea Olomouc. Rovněž děkujeme zaměstnancům Národního archivu, Archivu hl. m. Prahy a stavebního archivu MČ Prahy 1. Náš velký dík náleží i dalším lidem, kteří nám poskytli svůj čas a otevřeli vlastní archivy: jmenovitě to byli Jiří Gebert, Václav Hacmac, Vladimíra Leníčková a David Leníček (Len + K architekti), Natálie Mojžíšová, Adéla Procházková a Eva Kosáková a Karel Filsak ml. Za pomoc a rady děkujeme také Anně Kusákové z NPÚ a Jakubu Potůčkovi. -

Sketching Grounds

THE LIBRARY THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Digitized by tine Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of British Columbia Library http://www.archive.org/details/sketchinggroundsOOholm j. C M. KDTH bPECIAL 5UnnEK OR HOLIDAY NUM5EK TME 5TUDIO" 5KETCHING GROUNDS WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS IN COIDUKS 6 MONO TINT BY EMINENT LIVING • AKTI5T5 • WALLPAPCR /WIUT'^II^ Artists' on Colours^ Cni.5WICK A PRACTICAL PALETTE OF ONLY PURE& PERMANENT COLOURS M Colour cards and full particuiaraf as also of Selicail Water Colours, on application to I^rM/^ T\ S ^OJ^ WALL jLJL^i IvJpAPLn::) GUNTHER WAGNER, -RlLZr:3D^3nOULD5L 80 MILTON ST., LONDON, E.G. ?03Tf:i}100R3UC)/A]TTEDAT cniswicK DESIGNERS AND MAKERS OF ARTISTIC EMBROIDERIESofallKINOS LIBERTYc*cCO DRAWIMCS semt on approval POST FREE EMBROIDERY SILKS AND EVERY EM BROIDERY -WORK REQUISITE SUPPLIED. A BOOK COMTAININC lOO ORIGINAL DESIGNS FOR TRANSFER POST FREE ON APPLICATION LIBERTY Bt CO NEEDLEWORK DEPARTMENT EAST INDIA MOUSE RECEMT ST. W KODAK K CAMERAS KODAK CAMERAS and Kodak methods make photography easy and fascinating. With a Kodak, some Kodak Fihns and the Kodak Developing Machine, which make a complete and unique dayhght system of picture-making, you can produce portraits of relatives and friends, records of holiday travel and adventures, pictures of your sports and pastimes. NO DARKROOM NEEDED. THE KODAK BOOK, POST FREE, TELLS ALL ABOUT IT. OF ALL KODAK DEALERS and KODAK, Ltd., 57-61 Clerkenwell Road, London, E.G. q6 Bold Street, Liverpool ; 8g Grafton Street, Dublin ; 2 St. Nicholas Buildings. Newcastle ; Street, Buchanan Glasgow ; 59 Hrompton K!-74oad, S.W. ; 60 Cheapside, E.G. -

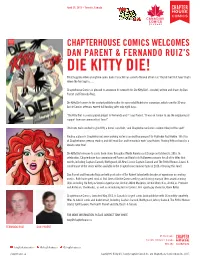

DIE KITTY DIE! What Happens When a Longtime Comic Book Character Has Come to the End of Her Run? You Kill Her! but How? That’S Where the Fun Begins…

April 25, 2015 – Toronto, Canada CHAPTERHOUSE COMICS WELCOMES DAN PARENT & FERNANDO RUIZ’S DIE KITTY DIE! What happens when a longtime comic book character has come to the end of her run? You kill her! But how? That’s where the fun begins….. Chapterhouse Comics is pleased to announce its newest title: Die Kitty Die! - created, written and drawn by Dan Parent and Fernando Ruiz. Die Kitty Die! comes to the upstart publisher after its successful Kickstarter campaign, which saw the 30-year Archie Comics veterans exceed full funding after only eight days. “Die Kitty Die! is a very special project for Fernando and I” says Parent, “It was an honour to see the outpouring of support from our community of fans!” ‘And now, we’re excited to give Kitty a home’ says Ruiz, ‘and Chapterhouse Comics seemed like just the spot!’ Finding a place in Chapterhouse’s ever-growing roster is an exciting prospect for Publisher Fadi Hakim. ’All of us at Chapterhouse grew up reading and still read Dan and Fernando’s work’ says Hakim. ‘Having Kitty on board is a dream come true!’ Die Kitty Die! releases to comic book stores throughout North America and Europe on October 26, 2016. In celebration, Chapterhouse has commissioned Parent and Ruiz to do Halloween variants for all of its titles that month, including Captain Canuck, Northguard, All-New Classic Captain Canuck and The Pitiful Human-Lizard. A small teaser of the series will be available in the Chapterhouse Summer Special 2016, releasing this June! Dan Parent and Fernando Ruiz are both graduates of The Kubert School with decades of experience in creating comics. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Truth, Justice, and the Canadian Way: the War-Time Comics of Bell Features Publications Ivan Kocmarek Hamilton, Ontario

Truth, Justice, and the Canadian Way: The War-Time Comics of Bell Features Publications Ivan Kocmarek Hamilton, Ontario 148 What might be called the “First Age of Canadian Comics”1 began on a consum- mately Canadian political and historical foundation. Canada had entered the Second World War on September 10, 1939, nine days after Hitler invaded the Sudetenland and a week after England declared war on Germany. Just over a year after this, on December 6, 1940, William Lyon MacKenzie King led parliament in declaring the War Exchange Conservation Act (WECA) as a protectionist measure to bolster the Canadian dollar and the war economy in general. Among the paper products now labeled as restricted imports were pulp magazines and comic books.2 Those precious, four-colour, ten-cent treasure chests of American culture that had widened the eyes of youngsters from Prince Edward to Vancouver Islands immedi- ately disappeared from the corner newsstands. Within three months—indicia dates give March 1941, but these books were probably on the stands by mid-January— Anglo-American Publications in Toronto and Maple Leaf Publications in Vancouver opportunistically filled this vacuum by putting out the first issues of Robin Hood Comics and Better Comics, respectively. Of these two, the latter is widely considered by collectors to be the first true Canadian comic book becauseRobin Hood Comics Vol. 1 No. 1 seems to have been a tabloid-sized collection of reprints of daily strips from the Toronto Telegram written by Ted McCall and drawn by Charles Snelgrove. Still in Toronto, Adrian Dingle and the Kulbach twins combined forces to release the first issue of Triumph-Adventure Comics six months later (August 1941), and then publisher Cyril Bell and his artist employee Edmund T. -

WARP Cathy Palmer-Lister the Outer Limits, Presentation and Discussion Led by Sylvain [email protected] St-Pierre, Followed by Screening of an Episode

MonSFFA’ s Executive MonSFFA CALENDAR OF EVENTS President Except where noted, all MonSFFA meetings are held Cathy Palmer-Lister SATURDAYS from 1:00 P.M. to 5:00 P.M. [email protected] Espresso Hotel, Salle St-François, 1005 Guy Street, corner René Lévesque. Vice-President Keith Braithwaite NB: If you do not find us in St François, please ask at the front desk. We are sometimes [email protected] moved to other rooms. Programming subject to change. Treasurer Check our website for latest developments. Sylvain St-Pierre [email protected] April 13 Appointed Positions Theme: Dimensions of the Imagination PR, Membership, editor of Impulse Keith Braithwaite NOON: Screening of an episode of Twilight Zone [email protected] Rod Serling’s Twilight Zone, presentation and discussion led by Keith Braithwaite Web Master & Editor of WARP Cathy Palmer-Lister The Outer Limits, presentation and discussion led by Sylvain [email protected] St-Pierre, followed by screening of an episode. [email protected] NOTE: Start bringing in junk for next month’s workshop! Keeper of the Lists Josée Bellemare May 11 On the Cover THEME: Spaceships! Vic Ballantine, art by Marquisew A-Hunting-We-Will-Go: Griffintown recently appeared on an Vic is largely made of various prosthetic parts and computer episode of “World’s Scariest Hauntings”, a program which electronics. Learn more about Vic and the artist on page 14. features ghostly hauntings from around the world! The spirit realm is rich in history which is both fascinating and incredible, and Lindsay Brown is going to tell us all about it! The Utopia Planitia Shipyards Competition: We will begin Contact us with a demonstration of 3D printing by Mark Burakoff, then while the machine runs, we’ll start building our spaceships! MonSFFA c/o Sylvain St-Pierre Sunday, June 9 4456 Boul. -

Global Worship Service: Celebrating the Power and Presence of God Tuesday, July 14, 2020, 9 A.M

Global Worship Service: Celebrating the Power and Presence of God Tuesday, July 14, 2020, 9 a.m. ET [:09] Multiple Singers: When peace like a river attendeth my way, when sorrows like sea billows roll, whatever my lot thou hast taught me to say, "It is well, it is well with my soul!" It is well, it is well, with my soul, with my soul. It is well, it is well with my soul! Though Satan should buffet, though trials should come, let this blest assurance control: that Christ has regarded my helpless estate and hath shed his own blood for my soul. It is well, it is well, with my soul, with my soul. It is well, it is well with my soul! My sin, oh, the bliss of this glorious thought, my sin, not in part but the whole is nailed to the cross and I bear it no more. Praise the Lord, praise the Lord, oh, my soul. It is well, it is well, with my soul, with my soul. It is well, it is well with my soul! [3:40] Rebecca Ochong: Greetings to each of you. For those of you who got up very early or those who are joining us at the end of a long day, thank you for making time to come together in worship. We are really glad you’re here. During this service, at several points you will be invited to enter responses in the chat box. Please note that we may experience a bit of a delay, but Paul Hamalian, our steward of cultural and spiritual services, will voice as many of those as possible. -

Dundee City Archives: Subject Index

Dundee City Archives: Subject Index This subject index provides a brief overview of the collections held at Dundee City Archives. The index is sorted by topic, and in some cases sub-topics. The page index on the next page gives a brief overview of the subjects included. The document only lists the collections that have been deposited at Dundee City Archives. Therefore it does not list records that are part of the Dundee City Council Archive or any of its predecessors, including: School Records Licensing Records Burial Records Minutes Planning Records Reports Poorhouse Records Other council Records If you are interested in records that would have been created by the council or one of its predecessors, please get in contact with us to find out what we hold. This list is update regularly, but new accessions may not be included. For up to date information please contact us. In most cases the description that appears in the list is a general description of the collection. It does not list individual items in the collections. We may hold further related items in collections that have not been catalogued. For further information please contact us. Please note that some records may be closed due to restrictions such as data protection. Other records may not be accessible as they are too fragile or damaged. Please contact us for further information or check access restrictions. How do I use this index? The page index on the next page gives a list of subjects covered. Click on the subject in the page index to be taken to main body of the subject index. -

MUNDANE INTIMACIES and EVERYDAY VIOLENCE in CONTEMPORARY CANADIAN COMICS by Kaarina Louise Mikalson Submitted in Partial Fulfilm

MUNDANE INTIMACIES AND EVERYDAY VIOLENCE IN CONTEMPORARY CANADIAN COMICS by Kaarina Louise Mikalson Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia April 2020 © Copyright by Kaarina Louise Mikalson, 2020 Table of Contents List of Figures ..................................................................................................................... v Abstract ............................................................................................................................. vii Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... viii Chapter 1: Introduction ....................................................................................................... 1 Comics in Canada: A Brief History ................................................................................. 7 For Better or For Worse................................................................................................. 17 The Mundane and the Everyday .................................................................................... 24 Chapter outlines ............................................................................................................. 30 Chapter 2: .......................................................................................................................... 37 Mundane Intimacy and Slow Violence: ........................................................................... -

REM E. Bow the Letter Nelly E.I Katy Perry E.T Cam Zoller Earl Didn't Die

REM E. Bow The Letter Nelly E.I Katy Perry E.T Cam Zoller Earl Didn't Die Weeknd Earned It Penguins Earth Angel UB40 Earth dies screaming Michael Jackson Earth Song Ricochet Ease My Troubled Mind Michael Jackson and Diana Ross Ease On Down The Road Jerry Reed East Bound and Down Commodores Easy Rascal Flatts & Natasha Bedingfield Easy Kiss Easy as it Seems George Strait Easy Come Easy Go Clint Black and Lisa Hartman Easy For Me To Say Terri Clark Easy From Now On Uriah Heep Easy Livin' Charlie Rich Easy Look Three Dog Night Easy To Be Hard Five For Fighting Easy Tonight Weird Al Yankovic Eat It Krokus Eat The rich Aerosmith Eat The Rich Wheeler Walker Jr Eatin Pussy/Kickin Ass Stevie Wonder & Paul McCartney Ebony And Ivory Everyly Brothers Ebony Eyes Trapt Echo Martha & The Muffins Echo Beach Pink Floyd Eclipse Sound of Music Edelweis Vince Hill Edelweiss Lady Gaga Edge of Glory Stevie Nicks Edge of Seventeen TED GÄRDESTAD Egen måne Beyonce Ego Beatles Eight Days a Week Alanis Morissette Eight Easy Steps Byrds Eight Miles High Kathy Mattea Eighteen Wheels And A Dozen Roses Marty Robbins El Paso City Amy Grant El Shaddai Sia Elastic Heart Pearl Jam Elderly woman Behind a Counter In A Small Town Low Millions Eleanor Alice Cooper Elected Eddie Grant Electric Avenue Lady Gaga Electric Chapel Marcia Griffiths Electric Slide REM Electrolite INXS Elegantly Wasted Tears for Fears Elemental Moulin Rouge Elephant Love Medley U2 Elevation Three Dog Night Eli's Coming Billy Gilman Elizabeth Bob Lind Elusive Butterfly Oak Ridge Boys Elvira Confederate -

Historical Note1 Version LS 180109

Curling in the Footsteps of History INTRODUCTION – SOURCES AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The pioneering Canadian tour took place in January and February 1909. This important tour set the tone for future tours of Scotland from Canada. Like all tours, true stamina was required of the party – especially at the start of the twentieth century when planes and email were but dreams! I do hope that you enjoy reading of their exploits while here in Scotland. A fuller version of the whole story is available in the 1910 RCCC Annual and that was my primary source for information. There is a list below of all my sources. • Season 1909 – 1910 Royal Caledonian Curling Club Annual for tour details • www.clydebuiltships.co.uk for the picture of the Empress of Ireland on page 4 and for ship’s dimensions and launch date • 2009 Canadian Tour to Scotland website www.strathconacup100.ca/ for the picture of Lord Strathcona on page 2 and the picture and details of Alexander Logan on page 8 • Malcolm Patrick, member of Watsonian Curling Club and fellow member of the East Team on the 2003 Centenary Scottish Tour to Canada for details of the informal outdoor game at Watsonian CC on page 10 • Ahoy – Mac’s Web Log for details of the sinking of the Empress of Ireland • Ian Mackay for the picture of the tour badge on page 12 • Ainslie Smith, Captain of the West Team and team mate on the 2003 Centenary Scottish Tour to Canada for the copy of the Banquet Menu on pages 16, 17 and 18 • Lindsay Scotland, webmaster of the Centenary Tour to Canada, 2003 www.ccct2003.fsnet.co.uk/ for photographs of the Strathcona Cup on pages 21, 22 and 23 • David Smith, for his ‘Curling Places of Scotland’, version June 2008, which is available on the Royal Caledonian Curling Club website: www.royalcaledoniancurlingclub.org under ‘About RCCC > Origin & History’ Robin Copland Balerno January 2009 1 Curling in the Footsteps of History TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE – PLANNING AND PREPARATION ................................................. -

Netflix & Chill Women in Punk Be a Mermaid Bygone Boozers

Winter 2016 Women in Punk Fighting for musical fairness Netflix & Chill Hookups through time Be a Mermaid How to earn your fins Bygone Boozers Old Ottawa’s drinking class WEEKEND WARRIORS An inside look at students in the military Ottawa MORE HITS. LESS COMMERCIALS. YOUR CAREER. ADVANCED. School Of Media and Design :LWKDJUDGXDWHFHUWLÀFDWH\RXFDQWDNH\RXUTXDOLÀFDWLRQVWRWKHQH[WOHYHO %RRVW\RXUFDUHHUZLWKKLJKGHPDQGVSHFLDOL]DWLRQVIRU\RXUFKRVHQÀHOG Interactive Media Management Scriptwriting Brand Management Kitchen and Bath Design Learn more about these exciting programs: DOJRQTXLQFROOHJHFRPPHGLDDQGGHVLJQ 6 inter 201 inter W LOUNGE 8 Zamboni Man 10 Finding Buddha 12 Sweet Emotions 14 Politically Plaster 15 Inspiring Minds 16 Buttin’ Out 17 Jocks Strapped 18 He Shoots, He Po 19 Three’s Company 20 Dragon Slayers Pg 40 Pg 15 Pg 36 22 A Stand-Up Time FEATURES 24 Full Metal Textbook An inside look at students in the military 28 Defying Diagnosis Overcoming learning disabilities Pg 42 32 The Art of Risk People who pursue their dream careers 36 Women Can Rock Females take back the punk scene CHEATSHEET 40 Not Child’s Play 42 Part of Their World 45 What’s Your Sign? BACK OF BOOK 46 Netflix& Chill Pg 28 Photos clockwise from left: Chelsea Lau, Aidan Cullis, Allison Larocque, Ilana Reimer, Amely Coulombe. Illustration: Katrin Emery winter 2016 GLUEottawa.com 05 Contributors Chris Lowrey: Writer Chris Lowrey has consistently stepped up to the plate whenever we’ve needed him while producing this issue of Glue. His ability to be THE TALENT handed a task and quickly turn around with a finely polished product wascrucial for our success.