ED290864.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lakshadweep Action Plan on Climate Change 2012 2012 333333333333333333333333

Lakshadweep Action Plan on Climate Change 2012 2012 333333333333333333333333 LAKSHADWEEP ACTION PLAN ON CLIMATE CHANGE (LAPCC) UNION TERRITORY OF LAKSHADWEEP i SUPPORTED BY UNDP Lakshadweep Action Plan on Climate Change 2012 LAKSHADWEEP ACTION PLAN ON CLIMATE CHANGE (LAPCC) Department of Environment and Forestry Union Territory of Lakshadweep Supported by UNDP ii Lakshadweep Action Plan on Climate Change 2012 Foreword 2012 Climate Change (LAPCC) iii Lakshadweep Action Plan on Lakshadweep Action Plan on Climate Change 2012 Acknowledgements 2012 Climate Change (LAPCC) iv Lakshadweep Action Plan on Lakshadweep Action Plan on Climate Change 2012 CONTENTS FOREWORD .......................................................................................................................................... III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................... IV EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. XIII PART A: CLIMATE PROFILE .............................................................................................................. 1 1 LAKSHADWEEP - AN OVERVIEW ............................................................................................. 2 1.1 Development Issues and Priorities .............................................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Baseline Scenario of Lakshadweep ............................................................................................................................ -

N RT ~Nnua Rt 1979-80

. N RT ~nnua rt 1979-80 T.2,gN6:1 L0- 192236 ANNUAL REPORT 1979-80 ANNUAL REPORT 1979-80 (! ;{ fft ~ 3Hi c;!t NC:i:£RT ~~~~ ~f~ afl~T<t afT~ srf~&1'Uf qf~~~ NATIONAL COUNCIL OF EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH AND TRAINING December 1980 Pausa 1~Q~. PD 1.5 T SD @ National Council of Educational Research and Training, 1980 Published by Shri V.K. Pandit, Secretary, National Council ol Educa· tiona! Research and Training, Sri Aurobindo Marg, New Delhl-110016, and printed at Ajanta Book Binders and Printers, Laxmi Nagar, Delhi-110092 CONTENTS Pages Acknowledgemeats vii 1. NCERT: Role and Functions 1 2. Main Directions and Future Outlook 13 3. Early Childhood Education 18 4. Universalization of Elementary Education 24 5. Education of the Disadvantaged 32 6. Curriculum and Textbook Development 36 - 7. Population Education 49 8. Education of Teachers and other Personnel 53 9. Educational Technology 67 10. Measurement and Evaluation 76 11. Survey, Data Processing and Documentation 80 12. Research and Innovations 84 13. Extension and Working with .States 127 14. Search for Talent 143 15. Publications 150 16. ·International Assistance and International Relations 164 17. Receipts and Payments 184 Appendices 187 A. Grants given by the Council to Professional Educational Organisations during 1979-80. 189 B. Field Advisers of the Council 190 c. Composition of Committees 192 D. Major Decisions 1aken by the Committees during 1979-80 226 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS THE National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) is indebted to the Union Minister of Education and Culture for his keen interest in its affairs. -

Education Booklet 2018.Cdr

Quality Education for All INITIATIVES & INNOVATIONS Transforming Delhi Education Deputy Chief Minister Govenment of NCT of Delhi Delhi's school education reforms have been recognised across the country and the world as a benchmark for policymakers. The dramatic turnaround in the condition of Delhi's government schools has brought us closer to our goal of providing quality and accessible education to every child in Delhi. Education is a leveller in an unequal society like ours. The only way to build a more just society is by ensuring equal opportunity for all. The remarkable improvement in government schools has led to a narrowing of the acute class divide between children studying in private and government schools. We have operated on the principle of “No Child Left Behind” with a focus on ensuring every single child’s interests are looked after. Whether it is through large scale upgrade of building infrastructure and capacity expansion, or through advanced teacher training focused on improving learning outcomes, the government's interventions have been thoughtfully designed to create maximum impact. Delhi government schemes like Chunauti 2018, strengthening of SMCs and the Mentor Teacher Program have attracted academic researchers from across the world. In fact, Harvard University is conducting a study assessing the impact of our work on SMCs. The last three years have been spectacular for Delhi's government schools. As Education Minister, I can only be proud of the progress we have made. Warm regards,. Manish Sisodia Chief Secretary Government of NCT of Delhi Education of students, whether at school level or for higher and technical education, must be both comprehensive and holistic. -

Islands, Coral Reefs, Mangroves & Wetlands In

Report of the Task Force on ISLANDS, CORAL REEFS, MANGROVES & WETLANDS IN ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS For the Eleventh Five Year Plan 2007-2012 Government of India PLANNING COMMISSION New Delhi (March, 2007) Report of the Task Force on ISLANDS, CORAL REEFS, MANGROVES & WETLANDS IN ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS For the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-2012) CONTENTS Constitution order for Task Force on Islands, Corals, Mangroves and Wetlands 1-6 Chapter 1: Islands 5-24 1.1 Andaman & Nicobar Islands 5-17 1.2 Lakshwadeep Islands 18-24 Chapter 2: Coral reefs 25-50 Chapter 3: Mangroves 51-73 Chapter 4: Wetlands 73-87 Chapter 5: Recommendations 86-93 Chapter 6: References 92-103 M-13033/1/2006-E&F Planning Commission (Environment & Forests Unit) Yojana Bhavan, Sansad Marg, New Delhi, Dated 21st August, 2006 Subject: Constitution of the Task Force on Islands, Corals, Mangroves & Wetlands for the Environment & Forests Sector for the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (2007- 2012). It has been decided to set up a Task Force on Islands, corals, mangroves & wetlands for the Environment & Forests Sector for the Eleventh Five-Year Plan. The composition of the Task Force will be as under: 1. Shri J.R.B.Alfred, Director, ZSI Chairman 2. Shri Pankaj Shekhsaria, Kalpavriksh, Pune Member 3. Mr. Harry Andrews, Madras Crocodile Bank Trust , Tamil Nadu Member 4. Dr. V. Selvam, Programme Director, MSSRF, Chennai Member Terms of Reference of the Task Force will be as follows: • Review the current laws, policies, procedures and practices related to conservation and sustainable use of island, coral, mangrove and wetland ecosystems and recommend correctives. -

Agatti Island, UT of Lakshadweep

Socioeconomic Monitoring for Coastal Managers of South Asia: Field Trials and Baseline Surveys Agatti Island, UT of Lakshadweep Project completion Report: NA10NOS4630055 Project Supervisor : Vineeta Hoon Site Coordinators: Idrees Babu and Noushad Mohammed Agatti team: Amina.K, Abida.FM, Bushra M.I, Busthanudheen P.K, Hajarabeebi MC, Hassan K, Kadeeshoma C.P, Koyamon K.G, Namsir Babu.MS, Noorul Ameen T.K, Mohammed Abdul Raheem D A, Shahnas beegam.k, Shahnas.K.P, Sikandar Hussain, Zakeer Husain, C.K, March 2012 This volume contains the results of the Socioeconomic Assessment and monitoring project supported by IUCN/ NOAA Prepared by: 1. The Centre for Action Research on Environment Science and Society, Chennai 600 094 2. Lakshadweep Marine Research and Conservation Centre, Kavaratti island, U.T of Lakshadweep. Citation: Vineeta Hoon and Idrees Babu, 2012, Socioeconomic Monitoring and Assessment for Coral Reef Management at Agatti Island, UT of Lakshadweep, CARESS/ LMRCC, India Cover Photo: A reef fisherman selling his catch Photo credit: Idrees Babu 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 7 Acknowledgements 8 Glossary of Native Terms 9 List of Acronyms 10 1. Introduction 11 1.1 Settlement History 11 1.2 Dependence on Marine Resources 13 1.3 Project Goals 15 1.4 Report Chapters 15 2. Methodology of Project Execution 17 2.1 SocMon Workshop 17 2.2 Data Collection 18 2.3 Data Validation 20 3. Site Description and Island Infrastructure 21 3.1 Site description 23 3.2. Community Infrastructure 25 4. Community Level Demographics 29 4.1 Socio cultural status 29 4.2 Land Ownership 29 4.3 Demographic characteristics 30 4.4 Household size 30 4.5. -

The Union Territories (Direct Election to the House of the People) Act, 1965 Arrangement of Sections ___

THE UNION TERRITORIES (DIRECT ELECTION TO THE HOUSE OF THE PEOPLE) ACT, 1965 _______________ ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS ___________ SECTIONS 1. Short title. 2. Definitions. 3. Direct election to fill the seats in the House of the People allotted to certain Union territories. 4. [Repealed.] 5. [Repealed.] 6. Provision as to sitting member. 1 THE UNION TERRITORIES (DIRECT ELECTION TO THE HOUSE OF THE PEOPLE) ACT, 1965 ACT NO. 49 OF 1965 [22nd December, 1965.] An Act to provide for direct election in certain Union territories for filling the seats allotted to them in the House of the People and for matters connected therewith. BE it enacted by Parliament in the Sixteenth Year of the Republic of India as follows:— 1. Short title.—This Act may be called the Union Territories (Direct Election to the House of the People) Act, 1965. 2. Definitions.—In this Act— (a) “parliamentary constituency” has the same meaning as in the Representation of the People Act, 1950 (43 of 1950); (b) “sitting member” means a person who immediately before the commencement of this Act is a member of the House of the People; (c) “Union territory” means any of the Union territories of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, 1[Lakshadweep] and Dadra and Nagar Haveli. 3. Direct election to fill the seats in the House of the People allotted to certain Union territories.—At the next general election to the House of the People and thereafter, the seats allotted under section 3 of the Representation of the People Act, 1950 (43 of 1950) to the Union territories in the House of the People shall be seats to be filled by persons chosen by direct election and for that purpose each Union territory shall form one parliamentary constituency. -

Ii. Delhi College of Engineering

-661- XVI. Technical Education 1. Directorate of Technical Education A well-planned system of technical education is a pre-requisite to sustain the rapid pace of development required in our country. Such a system will be called upon to translate the imperatives of modern manufacturing process, state-of-art technology, diversified technological changes and complex training requirements resulting from these changes, into the educational planning process. The future goals and objectives of the technical education system are to produce manpower needed to meet these diversified requirements of the user system. Directorate of Training and Technical Education coordinates its training programme to match with the policy of Government of Delhi to encourage the development and establishment of non- polluting, higher value-added and service-oriented industries. Following are the major thrust areas requiring attention: • Removal of obsolescence and modernisation of laboratories and workshops. • Frequent updation of curricula to include latest development in technologies. • Introduction of programmes in emerging areas like Computer Engineering, Microprocessors, Manufacturing Technology, Printing and Packing, Plastic, Chemical, Environmental Engineering and Technology, Fashion Technology and Public Health. • Initiation of Continuing Education programmes to train and retrain working technicians to acquire new trends and developments. • Concentration on development of managerial and entrepreneurial skills and innovative abilities. • Consolidation of existing facilities and optimize utilisation of available resources. • Improvement of quality and standard of Technician Education. • Interaction with Industry and the Community. -662- For imparting technical education at undergraduate and postgraduate level, there are 5 institutions namely Delhi College of Engineering, Netaji Subhas Institute of Technology, College of Art, College of Pharmacy and Mahila Institute of Technology. -

Diversity and Inclusion in Higher Education: a Study of Selected Institutions in Delhi

CPRHE Research Report Series 1.2 Diversity and Inclusion in Higher Education: A Study of Selected Institutions in Delhi C. V. Babu Satyendra Thakur Nitin Kumar July, 2019 Disclaimer: The views in the publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Centre for Policy Research in Higher Education (CPRHE), National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration (NIEPA) , New Delhi National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration, 17-B, Sri Aurobindo Marg, New Delhi-110016 Research Study Co-ordinated by Nidhi S. Sabharwal and Malish C. M. Diversity and Inclusion in Higher Education: A Study of Selected Institutions in Delhi C. V. Babu Satyendra Thakur Nitin Kumar Centre for Policy Research in Higher Education National University of Educational Planning and Administration 17B Sri Aurobindo Marg New Delhi: 110016 July, 2019 Preface The Centre for Policy Research in Higher Education (CPRHE) is a specialised Centre established in the National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration (NIEPA). It is an autonomous centre funded by the UGC and its activities are guided by an Executive Committee which approves its programmes and annual budgets. The Centre promotes and carries out research in the area of higher education policy and planning. Ever since the Centre became fully operational in July 2014, it has been carrying out research studies in the thrust areas identified in the perspective plan and the programme framework of the Centre. The thrust areas for research include access and equity, quality, teaching and learning, governance and management, financing, graduate employability and internationalization of higher education. At present the Centre is implementing research studies in selected institutions in all major states of India. -

Parcel Post Compendium Online Pakistan Post PKA PK

Parcel Post Compendium Online PK - Pakistan Pakistan Post PKA Basic Services CARDIT Carrier documents international Yes transport – origin post 1 Maximum weight limit admitted RESDIT Response to a CARDIT – destination Yes 1.1 Surface parcels (kg) 50 post 1.2 Air (or priority) parcels (kg) 50 6 Home delivery 2 Maximum size admitted 6.1 Initial delivery attempt at physical Yes delivery of parcels to addressee 2.1 Surface parcels 6.2 If initial delivery attempt unsuccessful, Yes 2.1.1 2m x 2m x 2m No card left for addressee (or 3m length & greatest circumference) 6.3 Addressee has option of paying taxes or Yes 2.1.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Yes duties and taking physical delivery of the (or 3m length & greatest circumference) item 2.1.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m No 6.4 There are governmental or legally (or 2m length & greatest circumference) binding restrictions mean that there are certain limitations in implementing home 2.2 Air parcels delivery. 2.2.1 2m x 2m x 2m No 6.5 Nature of this governmental or legally (or 3m length & greatest circumference) binding restriction. 2.2.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Yes (or 3m length & greatest circumference) 2.2.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m No 7 Signature of acceptance (or 2m length & greatest circumference) 7.1 When a parcel is delivered or handed over Supplementary services 7.1.1 a signature of acceptance is obtained Yes 3 Cumbersome parcels admitted No 7.1.2 captured data from an identity card are Yes registered 7.1.3 another form of evidence of receipt is No Parcels service features obtained 5 Electronic exchange of information -

CV of Prof. Mohammad Akhtar Siddiqui

C. V. of Prof. Mohammad Akhtar Siddiqui 1. Name Dr. Mohammad Akhtar Siddiqui 2. Position Professor of Education (Retd.), IASE, Faculty of Education, Jamia Millia IslamiaUniversity, Jamia Nagar, New Delhi-110025 Former Chairperson, National Council for Teacher Education, a Statutory Body under the Ministry of Human Resource Development, Govt of India, New Delhi, 2008-11. Former Chairman, NCTE Review Committee - A High Powered committee appointed by MHRD, 2015-16. 3. Address for Correspondence 174/15, Ghaffar Manzil, Jamia Nagar, New Delhi – 110025, India Phones: (R): +91-11-26833700 E-mail: [email protected] 4. Academic & Professional - DES (University of Leeds, U.K.) Qualifications - Ph.D. (Education) Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi - M.Com.(University of Delhi) -M.Ed. (Himachal University) 5. Areas of Specialization Educational Management and Administration, Teacher Education, Comparative Education, Education of Disadvantaged groups and Minorities 6. Professional Experience 40 years of Teaching & Research in the field of Education 1 7. Administrative Experience 20 years 8. Publications & Related Research Work More than 60 publications including books, research papers, articles, chapters and research reports in the areas of specialization. 9. Academic & Administrative Positions held : S.N Positions held Period Served 1. Professor of Education, IASE, July 11, 2011 to February 28,2018. Faculty of Education, (Professor of Education since Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. August ,1993) 2. Chairperson, National Council for Teacher June 12, 2008 to July 10,2011 Education under Ministry of Human Resource Development, Govt. of India, New Delhi. 3. Professor and Dean, Faculty of Education, December 15, 2006 to Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. June 11, 2008 4. -

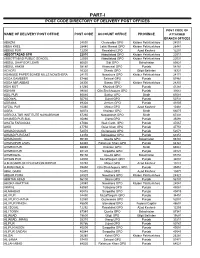

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

State of Public (School) Education in Delhi

WHITE PAPER State of Public (School) Education in Delhi March 2019 State of Public (School) Education in Delhi 1 Contents I. Foreword ............................................................................................................................................ 5 II. Acknowledgement .............................................................................................................................. 7 III. Status of Public School Education in Delhi .......................................................................................... 8 A. Outcome Indicators ................................................................................................................................ 8 Figure 1: Total number of schools and students in Delhi for 2013-14 to 2017-18 ...................................... 8 Figure 2: Fall in Enrolments from 2013-14 to 2017-18 in MCD, State Government and Central Government (K.V) Schools. ......................................................................................................................... 9 Table 1: Total Student Enrolments in Delhi Schools from 2013-14 to 2017-18 and estimated enrolment from 2018-19 to 2020-21. ......................................................................................................................... 10 Table 2: Total Dropouts in MCD & State Government Schools from 2014-15 to 2017-18. ....................... 11 Table 3: Change in Class I Enrolments from 2010-11 to 2017-18.............................................................