Skyfall: the "Aliens Sequence" in Monty Python's Life of Brian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Critical Companion to Terry Gilliam

H-Film A Critical Companion to Terry Gilliam Discussion published by Elif Sendur on Thursday, March 5, 2020 original authorship: [email protected] A Critical Companion to Terry Gilliam Edited by Ian Bekker, Sabine Planka and Philip van der Merwe Terry Gilliam is not only popular for being part of the Monty Python-troup but also for the movies he has directed in his own style, such as Time Bandits (1981), Brazil (1985), The Fisher King (1991), 12 Monkeys (1995) and The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus (2009). From dystopian to fantastic and magical settings, and worlds often populated by bizarre figures, Gilliam’s movies are united by their bizarreness in various ways. In this regard his oeuvre offers an incredibly fertile ground for critical examination, analysis and discussion. This anthology is designed to honour the year of Terry Gilliam’s eightieth birthday and is expected to be part of the A Critical Companion to Popular Directors series edited by Adam Barkman and Antonio Sanna. The goal is to showcase previously-unpublished essays that explore Gilliam’soeuvre from multidisciplinary perspectives. Contributions should focus on movies directed by Gilliam, starting with his debut (together with Terry Jones) Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), followed by his first solo debut Jabberwocky (1977), right up until his latest movie, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote (2018). We are particularly interested in interdisciplinary approaches to the subject which can illuminate the diverse facets of this director’s work as well as his visual style. There are several themes worth exploring when analyzing Gilliam’s works, utilizing any number of theoretical frameworks of one’s choosing. -

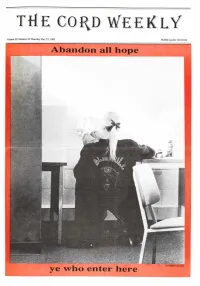

The Cord Weekly

THE CORD WEEKLY Volume 29, Number 25 Thursday Mar. 23,1989 Wilfrid Laurier University Abandon all hope ye who enter here Cord Photo: Liza Sardi The Cord Weekly 2 Thursday, March 23,1989 THE CORD WEEKLY |1 keliv/f!rent-a-car ; SAVE $5.00 ! March 23,1989 Volume 29, Number 25 ■ ON ANY CAR RENTAL ■ I Editor-in-Chief Cori Ferguson ■ NEWS Editor Bryan C. Leblanc Associate Jonathan Stover Contributors Tim Sullivan Frances McAneney COMMENT ■ ■ Contributors 205 WEBER ST. N. Steve Giustizia l 886-9190 l FEATURES Free Customer Pick-up Delivery ■ Editor vacant and Contributors Elizabeth Chen ENTERTAINMENT Editor Neville J. Blair Contributors Dave Lackie Cori Cusak Jonathan Stover Kathy O'Grady Brad Driver Todd Bird SPORTS Editor Brad Lyon Contributors Brian Owen Sam Syfie Serge Grenier Lucien Boivin Raoul Treadway Wayne Riley Oscar Madison Fidel Treadway Kenneth J. Whytock Janet Smith DESIGN AND ASSEMBLY Production Manager Kat Rios Assistants Sandy Buchanan Sarah Welstead Bill Casey Systems Technician Paul Dawson Copy Editors Shannon Mcllwain Keri Downs Contributors \ Jana Watson Tony Burke CAREERS Andre Widmer 112 PHOTOGRAPHY Manager Vicki Williams Technician Jon Rohr gfCHALLENGE Graphic Arts Paul Tallon Contributors Liza Sardi Brian Craig gfSECURITY Chris Starkey Tony Burke J. Jonah Jameson Marc Leblanc — ADVERTISING INFLEXIBILITY Manager Bill Rockwood Classifieds Mark Hand gfPRESTIGE Production Manager Scott Vandenberg National Advertising Campus Plus gf (416)481-7283 SATISFACTION CIRCULATION AND FILING Manager John Doherty Ifyou want theserewards Eight month, 24-issue CORD subscription rates are: $20.00 for addresses within Canada inacareer... and $25.00 outside the country. Co-op students may subscribe at the rate of $9.00 per four month work term. -

John Cleese & Eric Idle

JOHN CLEESE & ERIC IDLE TOGETHER AGAIN AT LAST…FOR THE VERY FIRST TIME Mesa, AZ • November 21 Tickets On-Sale Friday, June 17 at 10 a.m. June 15, 2016 (Mesa, AZ) – Still together again, Britain’s living legends of comedy, John Cleese and Eric Idle, announce their must see show John Cleese & Eric Idle: Together Again At Last…For The Very First Time in Mesa at Mesa Arts Center on November 21 at 7:30 p.m.! Tickets go on-sale to the public Friday, June 17 at 10 a.m. In Together Again At Last…For The Very First Time, Cleese and Idle will blend scripted and improvised bits with storytelling, musical numbers, exclusive footage and aquatic juggling to create a unique comedic experience with every performance. No two shows will be quite the same, thus ensuring that every audience feels like they’re seeing Together Again At Last… For The Very First Time, for the very first time. And now you know why the show is called that, don’t you? Following a successful run last fall in the Eastern US as well as a sold-out run in Australia and New Zealand this past February, their tour, John Cleese & Eric Idle: Together Again At Last…For The Very First Time will once again embark on some of the warmest (and driest) territories the US (and Canada) has to offer. The tour will take place from October 16 to November 26 and will see the British icons perform unforgettable sit-down comedy at premier venues in Victoria, Vancouver, Seattle, Spokane, Salem, Santa Rosa, San Francisco, San Jose, Thousand Oaks, Santa Barbara, Escondido, San Diego, Las Vegas, Mesa, Tucson, Albuquerque, El Paso with additional markets to be announced soon. -

The Rutles: All You Need Is Cash

SPOOFS The Rutles: All You Need Is Cash In the 1970s, Eric Idle, a former member of the legendary British com- edy team Monty Python, featured a Beatles parody song called “It Must Be Love” on Rutland Weekend Television, his own television show on BBC-2. The song had been written by Neil Innes, who had previously worked with Monty Python and the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band. The song was performed by ‘The Rutles’, a Beatles look-alike band featuring Neil Innes as the John Lennon character, and Eric Idle as the Paul McCartney character (vgl. Harry 1985: 69). In October 1976, the parody was shown on America’s NBC TV’s show Saturday Night Live as a se- quel to the running gag of a Beatles reunion for $3,000. The parody went down so well that Eric Idle and Neil Innes decided to produce a feature program about The Rutles for television. Idle, who was a close friend of George Harrison, was allowed to watch Neil Aspinall’s unreleased do- cumentary about The Beatles, called The Long and Winding Road. Aspi- nall’s film featured a bulk of famous footage of The Beatles, from their first televised performance at the Cavern Club in Liverpool to their last group performance on the roof of their Apple business building. Idle u- sed The Long and Winding Road as a model for his fake-documentary about The Rutles and basically re-told the history of The Beatles pro- jected upon this imaginary rock band, adding essential elements of par- ody and the Pythonesque sense of surreal humor. -

Monty Python's SPAMALOT

Monty Python’s Spamalot CHARACTERS Please note that the ages listed just serve as a guide. All roles are available and casting is open, and newcomers are welcome and encouraged. Also, character doublings are only suggested here and may be changed based on audition results and production needs. KING ARTHUR (Baritone, Late 30s-60s) – The King of England, who sets out on a quest to form the Knights of the Round Table and find the Holy Grail. Great humor. Good singer. THE LADY OF THE LAKE (Alto with large range, 20s-40s) – A Diva. Strong, beautiful, possesses mystical powers. The leading lady of the show. Great singing voice is essential, as she must be able to sing effortlessly in many styles and vocal registers. Sings everything from opera to pop to scatting. Gets angry easily. SIR ROBIN (Tenor/Baritone, 30s-40s) – A Knight of the Round Table. Ironically called "Sir Robin the Brave," though he couldn't be more cowardly. Joins the Knights for the singing and dancing. Also plays GUARD 1 and BROTHER MAYNARD, a long-winded monk. A good mover. SIR LANCELOT (Tenor/Baritone, 30s-40s) – A Knight of the Round Table. He is fearless to a bloody fault but through a twist of fate discovers his "softer side." This actor MUST be great with character voices and accents, as he also plays THE FRENCH TAUNTER, an arrogant, condescending, over-the-top Frenchman; the KNIGHT OF NI, an absurd, cartoonish leader of a peculiar group of Knights; and TIM THE ENCHANTER, a ghostly being with a Scottish accent. -

Sabina Stumberger

Divided God Sabina Stumberger Sabina Štumberger, visual anthropologist and video maker / researcher in the field of minority group issues; university lecturer in the field of visual art. Creative director and owner of an interactive media and video production company vmedia, Soho - London, UK, dealing with interactive media, DVD creation, screen design, graphic design and content production. She is actively managing the company since 2000, while remaining in the role of the designer and video content producer/maker. Some notable projects include Ghost in the Shell (Manga), Withnail and I (Handmade), Time Bandits (Handmade) inclusive of the documentary featuring work of Terry Gilliam and Michael Palin (Monty Python). Some notable clients include British Film Institute, Universal Films, Fox, Granada Television, Sony Pictures and Paramount. Some private projects: ‘We Have No Word for War’, 1995, featuring the culture of travelers; shown on festivals in Europe and overseas, NL; script and field collaboration; editor for the documentary ‘Bosnian Muslims – The Fate of World’, 1995, featuring the history of war in Bosnia; documentary projects of the Romani gatherings in Camargue, France; direction, script and edit, between 1990 and 1995. Part of the foundation group of the field project in the Romani settlements in Krsko, Slovenia in the capacity of anthropologist, researcher and video maker targeting the stereotypes between the settlers' and the Romani communities. By living within the community she became a cultural/social mediator between the two cultures and initiated the interactive creative projects in Romani settlements by using photographic and video camera as objects of communication and research.She is a visiting lecturer at the Communications for Illustrations department at the School of Art and Design, Derby since 2006 and a practicing visual artist focusing on site-specific and public art, exhibiting in the UK and overseas since 1990. -

He Dreams of Giants

From the makers of Lost In La Mancha comes A Tale of Obsession… He Dreams of Giants A film by Keith Fulton and Lou Pepe RUNNING TIME: 84 minutes United Kingdom, 2019, DCP, 5.1 Dolby Digital Surround, Aspect Ratio16:9 PRESS CONTACT: Cinetic Media Ryan Werner and Charlie Olsky 1 SYNOPSIS “Why does anyone create? It’s hard. Life is hard. Art is hard. Doing anything worthwhile is hard.” – Terry Gilliam From the team behind Lost in La Mancha and The Hamster Factor, HE DREAMS OF GIANTS is the culmination of a trilogy of documentaries that have followed film director Terry Gilliam over a twenty-five-year period. Charting Gilliam’s final, beleaguered quest to adapt Don Quixote, this documentary is a potent study of creative obsession. For over thirty years, Terry Gilliam has dreamed of creating a screen adaptation of Cervantes’ masterpiece. When he first attempted the production in 2000, Gilliam already had the reputation of being a bit of a Quixote himself: a filmmaker whose stories of visionary dreamers raging against gigantic forces mirrored his own artistic battles with the Hollywood machine. The collapse of that infamous and ill-fated production – as documented in Lost in La Mancha – only further cemented Gilliam’s reputation as an idealist chasing an impossible dream. HE DREAMS OF GIANTS picks up Gilliam’s story seventeen years later as he finally mounts the production once again and struggles to finish it. Facing him are a host of new obstacles: budget constraints, a history of compromise and heightened expectations, all compounded by self-doubt, the toll of aging, and the nagging existential question: What is left for an artist when he completes the quest that has defined a large part of his career? 2 Combining immersive verité footage of Gilliam’s production with intimate interviews and archival footage from the director’s entire career, HE DREAMS OF GIANTS is a revealing character study of a late-career artist, and a meditation on the value of creativity in the face of mortality. -

The Beatles on Film

Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 885.p 170758668456 Roland Reiter (Dr. phil.) works at the Center for the Study of the Americas at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests include various social and aesthetic aspects of popular culture. 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 885.p 170758668496 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 885.p 170758668560 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Graz, des Landes Steiermark und des Zentrums für Amerikastudien. Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de © 2008 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Layout by: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Edited by: Roland Reiter Typeset by: Roland Reiter Printed by: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-89942-885-8 2008-12-11 13-18-49 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02a2196899938240|(S. 4 ) T00_04 impressum - 885.p 196899938248 CONTENTS Introduction 7 Beatles History – Part One: 1956-1964 -

King Mob Echo: from Gordon Riots to Situationists & Sex Pistols

KING MOB ECHO FROM 1780 GORDON RIOTS TO SITUATIONISTS SEX PISTOLS AND BEYOND BY TOM VAGUE INCOMPLETE WORKS OF KING MOB WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES DARK STAR LONDON ·- - � --- Printed by Polestar AUP Aberdeen Limited, Rareness Rd., Altens Industrial Estate, Aberdeen AB12 3LE § 11JJJDJJDILIEJMIIENf1r 1f(Q) KIINCGr JMI(Q)IB3 JECCIHI(Q) ENGLISH SECTION OF THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL IF([J)IF ffiIE V ([J) IL lUilII ([J) W §IFIEIEIIJ) IHIII§il([J) ffiY ADDITIONAL RESEARCH BY DEREK HARRIS AND MALCOLM HOPKINS Illustrations: 'The Riots in Moorfields' (cover), 'The London Riots', 'at Langdale's' by 'Phiz' Hablot K. Browne, Horwood's 1792-9 'Plan of London', 'The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle', 'Oliver Twist Manifesto' by Malcolm McLaren. Vagrants and historical shout outs: Sandra Belgrave, Stewart Home, Mark Jackson, Mark Saunders, Joe D. Stevens at NDTC, Boz & Phiz, J. Paul de Castro, Blue Bredren, Cockney Visionaries, Dempsey, Boss Goodman, Lord George Gordon, Chris Gray, Jonathon Green, Jefferson Hack, Christopher Hibbert, Hoppy, Ian Gilmour, Ish, Dzifa & Simone at The Grape, Barry Jennings, Joe Jones, Shaun Kerr, Layla, Lucas, Malcolm McLaren, John Mead, Simon Morrissey, Don Nicholson-Smith, Michel Prigent (pre-publicity), Charlie Radcliffe, Jamie Reid, George Robertson & Melinda Mash, Dragan Rad, George Rude, Naveen Saleh, Jon Savage, Valerie Solanas, Carolyn Starren & co at Kensington Library, Mark Stewart, Toko, Alex Trocchi, Fred & Judy Vermorel, Warren, Dr. Watson, Viv Westwood, Jack Wilkes, Dave & Stuart Wise Soundtrack: 'It's a London Thing' Scott Garcia, 'Going Mobile' The Who, 'Living for the City' Stevie Wonder, 'Boston Tea Party' Alex Harvey, 'Catholic Day' Adam and the Ants, 'Do the Strand' Roxy Music', 'Rev. -

MONTY PYTHON at 50 , a Month-Long Season Celebra

Tuesday 16 July 2019, London. The BFI today announces full details of IT’S… MONTY PYTHON AT 50, a month-long season celebrating Monty Python – their roots, influences and subsequent work both as a group, and as individuals. The season, which takes place from 1 September – 1 October at BFI Southbank, forms part of the 50th anniversary celebrations of the beloved comedy group, whose seminal series Monty Python’s Flying Circus first aired on 5th October 1969. The season will include all the Monty Python feature films; oddities and unseen curios from the depths of the BFI National Archive and from Michael Palin’s personal collection of super 8mm films; back-to-back screenings of the entire series of Monty Python’s Flying Circus in a unique big-screen outing; and screenings of post-Python TV (Fawlty Towers, Out of the Trees, Ripping Yarns) and films (Jabberwocky, A Fish Called Wanda, Time Bandits, Wind in the Willows and more). There will also be rare screenings of pre-Python shows At Last the 1948 Show and Do Not Adjust Your Set, both of which will be released on BFI DVD on Monday 16 September, and a free exhibition of Python-related material from the BFI National Archive and The Monty Python Archive, and a Python takeover in the BFI Shop. Reflecting on the legacy and approaching celebrations, the Pythons commented: “Python has survived because we live in an increasingly Pythonesque world. Extreme silliness seems more relevant now than it ever was.” IT’S… MONTY PYTHON AT 50 programmers Justin Johnson and Dick Fiddy said: “We are delighted to share what is undoubtedly one of the most absurd seasons ever presented by the BFI, but even more delighted that it has been put together with help from the Pythons themselves and marked with their golden stamp of silliness. -

American Stage in the Park Bring Outdoors the Musical Comedy, SPAMALOT

For Immediate Release March 30, 2016 Contact: Zachary Hines Audience Development Associate (727) 823-1600 x 209 [email protected] American Stage in the Park Bring Outdoors the Musical Comedy, SPAMALOT. The Wait is Over with Monty Python’s Hilarious Musical opening April 15. St. Petersburg, FL – American Stage in the Park is excited to celebrate over 30 years outdoors with the musical, SPAMALOT which won the 2005 Tony Award for "Best Musical”, the 2005 Drama Desk Award for “Outstanding Musical” and the 2006 Grammy Award for “Best Musical Show Album”. The book and lyrics are by Eric Idle and music by John Du Prez and Eric Idle. The park title sponsor of American Stage in the Park is Bank of America. This outdoor production will be directed by Jonathan Williams and will feature eight lead actors and ten in the chorus. This large cast will feature six familiar faces from previous American Stage productions and twelve new faces to perform on stage in this hilarious musical. SPAMALOT’s Director, Jonathan Williams, is from the San Francisco Bay Area, a graduate of California Institute of the Arts, and co-founder of Capital Stage in Sacramento, CA. Williams said, “I could not be more excited to be directing SPAMALOT for American Stage. The script is such a great homage to Monty Python while standing on its own as a piece of musical theatre. I look forward to helming this project with the support of a great artistic team and a tremendously talented group of actors. I'm really hoping we hit this one out of the park (nudge nudge wink wink).” “SPAMALOT is a perfect fit for the celebratory, fun environment of American Stage in the Park. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter.