Open 1-Liu Shirley Thesisfinal.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

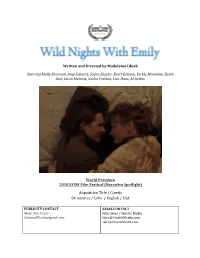

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek Starring Molly Shannon, Amy Seimetz, Susan Ziegler, Brett Gelman, Jackie Monahan, Kevin Seal, Dana Melanie, Sasha Frolova, Lisa Haas, Al Sutton World Premiere 2018 SXSW Film Festival (Narrative Spotlight) Acquisition Title / Cinetic 84 minutes / Color / English / USA PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES CONTACT Mary Ann Curto John Sloss / Cinetic Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FILM PRESS MATERIALS CONTACT and FILM CONTACT: Email: [email protected] DOWNLOAD FILM STILLS ON DROPBOX/GOOGLE DRIVE: For hi-res press stills, contact [email protected] and you will be added to the Dropbox/Google folder. Put “Wild Nights with Emily Still Request” in the subject line. The OFFICIAL WEBSITE: http://wildnightswithemily.com/ For news and updates, click 'LIKE' on our FACEBOOK page: https://www.facebook.com/wildnightswithemily/ "Hilarious...an undeniably compelling romance. " —INDIEWIRE "As entertaining and thought-provoking as Dickinson’s poetry.” —THE AUSTIN CHRONICLE SYNOPSIS THE STORY SHORT SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in " Wild Nights With Emily," a dramatic comedy. The film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman. LONG SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in the dramatic comedy " Wild Nights with Emily." The poet’s persona, popularized since her death, became that of a reclusive spinster – a delicate wallflower, too sensitive for this world. This film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (Susan Ziegler). After Emily died, a rivalry emerged when her brother's mistress (Amy Seimetz) along with editor T.W. -

Nysba Spring 2020 | Vol

NYSBA SPRING 2020 | VOL. 31 | NO. 2 Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal A publication of the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section of the New York State Bar Association In This Issue n A Case of “Creative Destruction”: Takeaways from the 5Pointz Graffiti Dispute n The American Actress, the English Duchess, and the Privacy Litigation n The Battle Against the Bots: The Legislative Fight Against Ticket Bots ....and more www.nysba.org/EASL NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION In The Arena: A Sports Law Handbook Co-sponsored by the New York State Bar Association and the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section As the world of professional athletics has become more competitive and the issues more complex, so has the need for more reliable representation in the field of sports law. Written by dozens of sports law attorneys and medical professionals, In the Arena: A Sports Law Handbook is a reflection of the multiple issues that face athletes and the attorneys who represent them. Included in this book are chapters on representing professional athletes, NCAA enforcement, advertising, sponsorship, intellectual property rights, doping, concussion-related issues, Title IX and dozens of useful appendices. Table of Contents Intellectual Property Rights and Endorsement Agreements How Trademark Protection Intersects with the Athlete’s EDITORS Right of Publicity Elissa D. Hecker, Esq. Collective Bargaining in the Big Three David Krell, Esq. Agency Law Sports, Torts and Criminal Law PRODUCT INFO AND PRICES 2013 | 539 pages Role of Advertising and Sponsorship in the Business of Sports PN: 4002 (Print) Doping in Sport: A Historical and Current Perspective PN: 4002E (E-Book) Athlete Concussion-Related Issues Non-Members $80 Concussions—From a Neuropsychological and Medical Perspective NYSBA Members $65 In-Arena Giveaways: Sweepstakes Law Basics and Compliance Issues Order multiple titles to take advantage of our low flat Navigating the NCAA Enforcement Process rate shipping charge of $5.95 per order, regardless of the number of items shipped. -

Download Press Release As PDF File

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS - PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: JULIEN’S AUCTIONS ANNOUNCES PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN Emmy, Grammy and Academy Award Winning Hollywood Legend’s Trademark White Suit Costume, Iconic Arrow through the Head Piece, 1976 Gibson Flying V “Toot Uncommons” Electric Guitar, Props and Costumes from Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, Little Shop of Horrors and More to Dazzle the Auction Stage at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills All of Steve Martin’s Proceeds of the Auction to be Donated to BenefitThe Motion Picture Home in Honor of Roddy McDowall SATURDAY, JULY 18, 2020 Los Angeles, California – (June 23rd, 2020) – Julien’s Auctions, the world-record breaking auction house to the stars, has announced PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN, an exclusive auction event celebrating the distinguished career of the legendary American actor, comedian, writer, playwright, producer, musician, and composer, taking place Saturday, July 18th, 2020 at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills and live online at juliensauctions.com. It was also announced today that all of Steve Martin’s proceeds he receives from the auction will be donated by him to benefit The Motion Picture Home in honor of Roddy McDowall, the late legendary stage, film and television actor and philanthropist for the Motion Picture & Television Fund’s Country House and Hospital. MPTF supports working and retired members of the entertainment community with a safety net of health and social -

Postfeminism and Urban Space Oddities in Broad City." Space Oddities: Difference and Identity in the American City

Lahm, Sarah. "'Yas Queen': Postfeminism and Urban Space Oddities in Broad City." Space Oddities: Difference and Identity in the American City. Ed. Stefan L. Brandt and Michael Fuchs. Vienna: LIT Verlag, 2018. 161-177. ISBN 978-3-643-50797-6 (pb). "VAS QUEEN": POSTFEMINISM AND URBAN SPACE ODDITIES IN BROAD CITY SARAH LAHM Broad City's (Comedy Central, since 2014) season one episode "Working Girls" opens with one of the show's most iconic scenes: In the show's typical fashion, the main characters' daily routines are displayed in a split screen, as the scene underline the differ ences between the characters of Abbi and Ilana and the differ ent ways in which they interact with their urban environment. Abbi first bonds with an older man on the subway because they are reading the same book. However, when he tries to make ad vances, she rejects them and gets flipped off. In clear contrast to Abbi's experience during her commute to work, Ilana intrudes on someone else's personal space, as she has fallen asleep on the subway and is leaning (and drooling) on a woman sitting next to her (who does not seem to care). Later in the day, Abbi ends up giving her lunch to a homeless person who sits down next to her on a park bench, thus fitting into her role as the less assertive, more passive of the two main characters. Meanwhile, Ilana does not have lunch at all, but chooses to continue sleeping in the of ficebathroom, in which she smoked a joint earlier in the day. -

'COMEDY CENTRAL's Hot List' Debuting Sunday, December 5 at 10:00 P.M.*

What Winter Cold? These Comedians are Bringing the Heat! Check Out the World Premiere of 'COMEDY CENTRAL's Hot List' Debuting Sunday, December 5 at 10:00 p.m.* NEW YORK, Nov. 16, 2010 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ -- COMEDY CENTRAL is unleashing a new "Hot List" of its star comics upon the world! See who makes the cut in the World Premiere of "COMEDY CENTRAL's Hot List," debuting Sunday, December 5 at 10:00 p.m. With the success of 2009's "Hot List," which included white-hot comedians Aziz Ansari, Donald Glover, Nick Kroll and Whitney Cummings, COMEDY CENTRAL is proving its prophetic prowess yet again by rolling out a bevy of break-through talent that audiences will soon have to reckon with. COMEDY CENTRAL has picked seven of the hottest comedians who have been on a hot streak in the clubs, on the Internet, in films and on television. This year's cream of the comedic crop includes Pete Holmes ("John Oliver's New York Stand-Up Show," "COMEDY CENTRAL Presents"), Reggie Watts ("Michael & Michael Have Issues"), Chelsea Peretti ("COMEDY CENTRAL Presents," "The Sarah Silverman Program"), Kurt Metzger ("Ugly Americans," "COMEDY CENTRAL Presents"), Kyle Kinane ("COMEDY CENTRAL Presents," "Last Call with Carson Daly"), Natasha Leggero ("COMEDY CENTRAL Presents," "Ugly Americans," "Last Comic Standing") and Owen Benjamin ("The House Bunny," "COMEDY CENTRAL Presents"). "COMEDY CENTRAL's Hot List" includes interviews with the comedians as well as clips from their various performances and day-in-the-life footage captured with a self-recorded flipcam. Tune in Sunday, December 5 at 10:00 p.m. -

Infant Sorrow and Friends Perform Songs from the Film 'GET HIM to the GREEK' Live One Night Only!

May 12, 2010 Infant Sorrow and Friends Perform Songs From the Film 'GET HIM TO THE GREEK' Live one Night Only! Featuring Special Appearances by: Infant Sorrow, Russell Brand, Jonah Hill, Carl Barat from The Libertines and Special Guests LOS ANGELES, May 12 /PRNewswire/ -- Infant Sorrow and Friends is a live one-night- only concert by performers from the upcoming comedy GET HIM TO THE GREEK at The Roxy on Monday, May 24. The evening features songs from the film and forthcoming album as performed by Infant Sorrow, Russell Brand, Carl Barat of the hugely popular U.K. band The Libertines, with special appearances by Jonah Hill and other surprise guests. The events begin at 8:00 PM, and the first 100 people to arrive at The Roxy will receive a limited edition Infant Sorrow T-shirt. Tickets go on sale Friday, May 14, at 10 AM. The album INFANT SORROW – GET HIM TO THE GREEK is available June 1 through Universal Republic. ABOUT GET HIM TO THE GREEK: GET HIM TO THE GREEK reunites Jonah Hill and Russell Brand with Forgetting Sarah Marshall director Nicholas Stoller in the story of a record company executive with three days to drag an uncooperative rock legend to Hollywood for a comeback concert. The comedy is the latest film from producer Judd Apatow (The 40-Year-Old Virgin, Knocked Up, Funny People) and arrives in theaters on June 4. www.gethimtothegreek.com MONDAY, MAY 24 THE ROXY 8:00 PM 9009 Sunset Boulevard, West Hollywood, CA 90069 ON SALE FRIDAY, MAY 14, AT 10 AM TICKETS AVAILABLE ONLINE AT WWW.LIVENATION.COM OR BY PHONE AT (877) 598-6671. -

Liberty City Guidebook

Liberty City Guidebook YOUR GUIDE TO: PLACES ENTERTAINMENT RESTAURANTS TABLE OF CONTENTS A very small percentage of individuals may experience epileptic seizures or blackouts when exposed to certain light patterns or flashing lights. Exposure to certain patterns or backgrounds on a television screen or when playing video games may trigger epileptic seizures or blackouts in these individuals. These conditions may trigger previously undetected epileptic symptoms or seizures in persons who have no history of prior seizures or epilepsy. If you, or anyone in your family, has an epileptic condition or has had seizures of any kind, consult your physician before playing. IMMEDIATELY DISCONTINUE use and consult your physician before resuming gameplay if you or your child experience any of the following health problems or symptoms: • dizziness • eye or muscle twitches • disorientation • any involuntary movement • altered vision • loss of awareness • seizures or convulsion. RESUME GAMEPLAY ONLY ON APPROVAL OF YOUR PHYSICIAN. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Use and handling of video games to reduce the likelihood of a seizure • Use in a well-lit area and keep as far away as possible from the television screen. • Avoid large screen televisions. Use the smallest television screen available. • Avoid prolonged use of the PLAYSTATION®3 system. Take a 15-minute break during each hour of play. • Avoid playing when you are tired or need sleep. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Stop using the system immediately if you experience any of the following symptoms: lightheadedness, nausea, or a sensation similar to motion sickness; discomfort or pain in the eyes, ears, hands, arms, or any other part of the body. If the condition persists, consult a doctor. -

America's Closet Door: an Investigation of Television and Its Effects on Perceptions of Homosexuality

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga UTC Scholar Student Research, Creative Works, and Honors Theses Publications 12-2014 America's closet door: an investigation of television and its effects on perceptions of homosexuality Sara Moroni University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Moroni, Sara, "America's closet door: an investigation of television and its effects on perceptions of homosexuality" (2014). Honors Theses. This Theses is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. America’s Closet Door An Investigation of Television and Its Effects on Perceptions of Homosexuality Sara Moroni Departmental Thesis The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga English Project Director: Rebecca Jones, PhD. 31 October 2014 Christopher Stuart, PhD. Heather Palmer, PhD. Joanie Sompayrac, J.D., M. Acc. Signatures: ______________________________________________ Project Director ______________________________________________ Department Examiner ____________________________________________ Department Examiner ____________________________________________ Liaison, Departmental Honors Committee ____________________________________________ Chair, Departmental Honors Committee 2 Preface The 2013 “American Time Use Survey” conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics calculated that, “watching TV was the leisure activity that occupied the most time…, accounting for more than half of leisure time” for Americans 15 years old and over. Of the 647 actors that are series regulars on the five television broadcast networks (ABC, CBS, The CW, Fox, and NBC) 2.9% were LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender) in the 2011-2012 season (GLAAD). -

The Garry Effect

MR. META Shandling in a press photo for his first groundbreaking sitcom, It’s Garry Shandling’s Show, which ran on Showtime from 1986 to 1990, and notably broke the fourth wall. now-familiar tropes of showing the studio audience and directly address- ing viewers. And then there’s that winking theme song: “This is the theme to Garry’s show/The theme to Garry’s show/Garry called me up and asked if I would write his theme song.” Incredibly, the show found a huge audience, powered in part by Shan- dling’s status as a stand-up comic whose nasal delivery, blown-out bouf- fant and sardonic observations (rou- tinely centered on his sexual prowess, or lack thereof) earned him frequent appearances on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show and a spot as one of its regular guest hosts. It also turned TELEVISION him into a role model for multiple generations of comedians. “He’s like the Replacements,” says Judd Apatow. The Garry Effect “A rock band that inspired a lot of peo- Judd Apatow’s HBO documentary aims to capture ple to start their own bands.” Garry Shandling’s lifetime of influence—as a Apatow included. For 25 years, the comedian, yes, but also as a human being. At comedy guru counted Shandling— who died of a heart attack in 2016 at more than four hours, it feels too short age 66—as a close friend and mentor. Apatow’s first contact was as a high school student, interviewing Shan- Try To imagine Television comedy works. Fly-on-the-wall camera dling for his school’s radio station. -

United States Court of Appeals for the West Ames Circuit ______MICHAEL GARY SCOTT, Plaintiff – Appellant, V

No. 16-345 _____________________________ United States Court of Appeals for the West Ames Circuit _____________________________ MICHAEL GARY SCOTT, Plaintiff – Appellant, v. SCRANTON GREETING CARDS CO., Defendant – Appellee. ____________________________ On Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of West Ames Civil Action No. 16-CV-3388 JOINT APPENDIX By Jason Harrow, HLS ‘11 In the United States Court of Appeals for the West Ames Circuit Michael G. Scott v. Scranton Greeting Cards, Co., No. 16-345 CONTENTS Order of the Court of Appeals (September 14, 2016) ...................................... 1 Notice of Appeal (August 13, 2016) ................................................................. 2 Judgment (August 12, 2016) ........................................................................... 3 Order and Opinion (August 12, 2016) ............................................................. 4 Notice of Motion to Dismiss (June 24, 2016).................................................. 18 Complaint (June 2, 2016) ................................................................................ 20 Exhibit A (article of December 2, 2015) ........................................................ 30 Exhibit B (greeting card) ............................................................................... 33 In the United States Court of Appeals for the West Ames Circuit Michael G. Scott v. Scranton Greeting Cards, Co., No. 16-345 ORDER Plaintiff-Appellant’s Motion for Appointment of Counsel is GRANTED. New counsel -

SECOND GROUP of PRESENTERS ANNOUNCED for 70Th EMMY® AWARDS SEPTEMBER 17

, FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SECOND GROUP OF PRESENTERS ANNOUNCED FOR 70th EMMY® AWARDS SEPTEMBER 17 Recent 70th Emmy Award Winner RuPaul Charles To Join Samantha Bee, Connie Britton, Benicio Del Toro and Television’s Top Talent To Present During Television Industry’s Most Celebrated Night (NoHo Arts District, Calif. – Sept. 12, 2018) — The Television Academy and Executive Producer Lorne Michaels today announced the second group of talent set to present the iconic Emmy statuette at the 70th Emmy® Awards on Monday, September 17. The presenters include: • Patricia Arquette (Escape at Dannemora) • Angela Bassett (9-1-1) • Eric Bana (Dirty John) • Samantha Bee (Full Frontal with Samantha Bee) – Outstanding Variety Talk Series, Outstanding Writing For A Variety Special • Connie Britton (Dirty John) • RuPaul Charles (RuPaul’s Drag Race) – 70th Emmy Award Winner for Outstanding Host For A Reality Or Reality-Competition Program • Benicio Del Toro (Escape at Dannemora) • Claire Foy (The Crown) – Outstanding Lead Actress In A Drama Series • Hannah Gadsby (Hannah Gadsby: Nanette) • Ilana Glazer (Broad City) • Abbi Jacobson (Broad City) • Jimmy Kimmel (Jimmy Kimmel Live!) – Outstanding Variety Talk Series • Elisabeth Moss (The Handmaid’s Tale) – Outstanding Lead Actress In A Drama Series, Outstanding Drama Series • Sarah Paulson (American Horror Story: Cult) – Outstanding Lead Actress In A Limited Series Or Movie • The Cast of Queer Eye, 70th Emmy Award Winner for Outstanding Structured Reality Program • Issa Rae (Insecure) – Outstanding Lead Actress In A Comedy Series • Andy Samberg (Brooklyn Nine-Nine, Saturday Night Live) • Matt Smith (The Crown) – Outstanding Supporting Actor In A Drama Series • Ben Stiller (Escape at Dannemora) The 70th Emmy Awards will telecast live from the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles on Monday, September 17, (8:00-11:00 PM ET/5:00-8:00 PM PT) on NBC. -

It's Not About the Sex Ization and Queerness in Ellen and the Ellen Degeneres Show

It's Not About the Sex ization and Queerness in Ellen and The Ellen Degeneres Show MARUSYA BOClURKlW Cette auteure examine les analogies raciales et les juxtaposi- star, whose latest television incarnation is as host ofNBC tions employkes dans la reprhsentation de Eden Degeneres daytime talk show, The EhnDegeneres Show. I will discuss comme uedette de tklkuision lesbienne. Ily eut au dkbut une the ways in which, throughout the history of lesbian sortie du placard hyper rkaliste du personnage Ellen Morgan representation, excessively racialized images mark narra- b La tklkuision en 1977 et comme conclusion elle analyse les tive junctures where normalcy has been put into question. gestes qui sont la marque de Degeneres, quand elle anime son Further, the projection of sexuality onto racialized figures kmission * The Ellen Defeneres- Show a. L huteure uoit h is a way forwhiteness to represent, yet also dissociate itself, trauers l'bistoire de la reprksentation des lesbiennes, des from its (abnormal?)desires. Indeed, as the opening quote images trks racistes quand h normalitk est inuoquhe. to this paper implies, aleitmotifof Degeneres' and Heche's (her then new love interest) media interviews during- the 0prah: Okay, soyou saw Ellen across a crowdedroom... coming-out period was a bizarre denial of the sexual nature oftheir relationship. Historically,white femininity Anne Heche: Ifell in love with aperson. has frequently been represented as that which transcends the sexual "fallibility" of the body itself (Dyer). Richard Oprah: And felt, what, some kind of sexual attrac- Dyer writes that white women's "very whiteness, their tion, you felt sexually attracted to her.