Samuel Ernest Vandiver, Jr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Granite Mansion: Georgia's Governor's Mansion 1924-1967

The Granite Mansion: Georgia’s Governor’s Mansion 1924-1967 Documentation for the proposed Georgia Historical Marker to be installed on the north side of the road by the site of the former 205 The Prado, Ansley Park, Atlanta, Georgia June 2, 2016 Atlanta Preservation & Planning Services, LLC Georgia Historical Marker Documentation Page 1. Proposed marker text 3 2. History 4 3. Appendices 10 4. Bibliography 25 5. Supporting images 29 6. Atlanta map section and photos of proposed marker site 31 2 Proposed marker text: The Granite Governor’s Mansion The Granite Mansion served as Georgia’s third Executive Mansion from 1924-1967. Designed by architect A. Ten Eyck Brown, the house at 205 The Prado was built in 1910 from locally- quarried granite in the Italian Renaissance Revival style. It was first home to real estate developer Edwin P. Ansley, founder of Ansley Park, Atlanta’s first automobile suburb. Ellis Arnall, one of the state’s most progressive governors, resided there (1943-47). He was a disputant in the infamous “three governors controversy.” For forty-three years, the mansion was home to twelve governors, until poor maintenance made it nearly uninhabitable. A new governor’s mansion was constructed on West Paces Ferry Road. The granite mansion was razed in 1969, but its garage was converted to a residence. 3 Historical Documentation of the Granite Mansion Edwin P. Ansley Edwin Percival Ansley (see Appendix 1) was born in Augusta, GA, on March 30, 1866. In 1871, the family moved to the Atlanta area. Edwin studied law at the University of Georgia, and was an attorney in the Atlanta law firm Calhoun, King & Spalding. -

Samuel Ernest Vandiver, Jr

OH Vandiver 01C Samuel Ernest Vandiver, Jr. interviewed by Mel Steeley and Ted Fitzsimmons Date: 6/25/86 Cassettes #439 (56 minutes) COPY OF ORIGINAL INTERVIEW ORIGINAL AT WEST GEORGIA UNIVERSITY Side One Fitzsimmons: Governor, we were talking about the integration of the university, and you said in making a decision you talked to a number of people, and among them Senator [Richard Brevard, Jr.] Russell. What was his advice? Vandiver: Well, I think you probably know what his situation was. He had fought these battles in the Senate for many, many years. And, of course, he knew from his practice of law and his familiarity with the law that I had no choice except to follow the law. That I couldn't, if I had defied the court, then I had no choice except to try to get the state of Georgia to secede again from the Union. And we'd tried that once and hadn't done too well that time. And so he knew that I had no choice. One thing that Betty [Sybil Elizabeth] Vandiver and I have talked about a great deal was her father was a federal judge; he was a judge of the northern district of Georgia. And he never had to deal with this situation. He knew it was probably coming, but he became ill with cancer, and he died in 1955 before this situation ever came before his court. And we've thought about it many times, that the Lord was kind to him. He would have had to rule in such a way that it would have been extremely difficult for him. -

Harold Paulk Henderson, Sr

Harold Paulk Henderson, Sr. Oral History Collection OH Vandiver 23 George Dekle Busbee Interviewed by Dr. Harold Paulk Henderson Date: 03-17-94 Cassette # 474 (26 Minutes, Side One Only) EDITED BY DR. HENDERSON Side One Henderson: This is an interview with former Governor George D. [Dekle] Busbee in his law office in Atlanta. The date is March 17, 1994. I am Dr. Hal Henderson. Good afternoon, Governor Busbee. Busbee: Good day. Henderson: Thank you very much for granting me this interview. Busbee: I'm delighted. Henderson: You served in the state House of Representatives the last two years of the [Samuel] Marvin Griffin [Sr.] administration and you served all four years of [Samuel] Ernest Vandiver's [Jr.] administration. Let me begin by asking you: what was your impression of the Marvin Griffin administration? Busbee: Well, of course, if you had to choose sides Marvin wouldn't have said that I was in his camp. I will say, however, that I was reminiscing with some people that served in the legislature with me back then and have served since I was governor, and we don't think it's as much fun as it used to be. I think he was a very colorful character and we had a great time, but I think that was former days for Georgia; that's not the era that we're in now. Henderson: Okay. How would you describe the relationship between Lieutenant Governor Vandiver and Governor Marvin Griffin? 2 Busbee: Well, the first real bitter fight that I became engaged in as a legislator was during the time that I was there [and] Marvin Griffin was governor, and we had the rural roads fight. -

Richard Russell, Jr

77//33//1133 RRiicchhaarrdRR uusssseellll,JJ rr.- WW iikkiippeeddiiaa,tt hheff rreeeee nnccyyccllooppeeddiiaa Richard Russell, Jr. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Richard Brevard Russsseell, Jr. (November 2, 1897 – January 21, 1971) was an American politician from Georgia. Richard Brevard Russell, Jr. A member of the Democratic Party, he briefly served as speaker of the Georgia house, and as Governor of Georgia (1931–33) before serving in the United States Senate for almost 40 years, from 1933 until his death in 1971. As a Senator, he was a candidate for President of the United States in the 1948 Democratic National Convention, and the 1952 Democratic National Convnvention. Russell was a founder and leader of the conservative coaoalilition that dominated Congress from 1937 to 1963, and at his death was the most senior member of the Senate. He was for decades a leader of Southern opposition to the civil rights movement. PrPresesidident prpro tempore of the UUnited States Senate In office Contents January 3, 1969 – January 21, 1971 Leader Mike Mansfield 1 Early life Carl Hayden 2 2 Governor of Georgigiaa Preceded by 3 Senate career Succeeded by Allen J. Ellender 4 Personal life Chairman of the Senate Committee on 5 Legacy Appropriations 6 References InIn office 7 Further sources January 3, 1969 – January 21, 1971 7.1 Primary sources 7.2 Scholarly secondary sources Leader Mike Mansfield 8 External links Preceded by Carl Hayden Succeeded by Allen Ellender Chairman of the Senate Committee on Armed Early life Services In office January 3, 1955 – January 3, 1969 Leader Lyndon B. Johnson Mike Mansfield Preceded by Leverett Saltonstall Succeeded by John C. -

S. Ernest Vandiver Interviewer: John F

S. Ernest Vandiver Oral History Interview –JFK #1, 5/22/1967 Administrative Information Creator: S. Ernest Vandiver Interviewer: John F. Stewart Date of Interview: May 22, 1967 Place of Interview: Atlanta, Georgia Length: 71 pp. Biographical Note Vandiver, S. Ernest; Governor of Georgia (1959-1963). Vandiver discusses his role in John F. Kennedy’s [JFK] presidential campaign in Georgia (1960), JFK’s push to gain southern support during this campaign, JFK’s policies regarding civil rights, and events that occurred during his presidency, among other issues. Access Restrictions No restrictions. Usage Restrictions Copyright of these materials has been passed to the United States Government upon the death of the interviewee. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. -

Georgia Lawyer Legacies

GBJ Feature GeorgiaGeorgia LawyerLawyer LegaciesLegacies by Sarah I. Coole, Jennifer R. Mason and Johanna B. Merrill Illustration by Marc Cardwell ith a Bar membership as diverse as (admitted to the Bar in 1982) knows what it means to honor the profession. She follows in the footsteps of Georgia’s—where people relocate to members of the Abbot-Hardeman family, dating back to the 1800s. On the Hardeman side, her mater- our cities from the other 49 states and nal great-great-great-grandfather Robert Vines W Hardeman served as lawyer, state representative countries as far away as China—it may be easy to for- and Superior Court judge in the Ocmulgee Circuit. Other Hardeman family lawyers include Abbot’s get that for a number of Georgia lawyers, the roots of great-grandfather, Robert Northington “R.N.” Hardeman (1894) and her grandfather, Robert their legal careers run deep. For some, they are but the Northington Hardeman Jr. (1915). Two paternal great-great uncles, Judge William Little Phillips and second generation: the beginning of a legal legacy that John Robert Phillips both practiced in Jefferson County. According to Judge Abbot, “If you were to may stretch for generations to come. Others, however, take a look at the cases on appeal out of the courts in Jefferson County, you would see that many are con- can find their last names in Georgia Bar Association nected with an Abbot, Phillips or Hardeman.” Judge Abbot’s view of lawyers and the legal profes- rosters from before the Civil War. sion was integrally shaped by how her father, James Carswell “Jim” Abbot (1951), and grandfather, William We asked the Bar’s membership to let us know if they Wright Abbot Jr. -

Carl Sanders: a Conversation Closed Captioning Script

CARL SANDERS: A CONVERSATION CLOSED CAPTIONING SCRIPT MUSIC Hoffman: He was Georgia’s new south governor and he guided the state through an era of great change. Carl Edward Sanders, Senior was born in Augusta in 1925. Smart and athletic he won a football scholarship to UGA. When World War II interrupted his studies, Sanders enlisted in the Army Air Force and he trained as a B-17 bomber pilot. After the War he returned to UGA and while in law school there he met Betty Bird Foy of Statesboro. They married in 1947 and settled in Augusta where Sanders entered politics. He was elected to the State House in 1954 and the State Senate in 1956. Only 6 years later at just 37 years old, the charismatic Sanders was elected Governor. A strong and progressive leader, Sanders focused first on education and reforming state government. He also supported civil rights. Sanders political career looked very promising, but a reelection defeat in 1970 turned him from public office to the law and other ventures. He established his own law practice, now a prestigious international law firm and threw himself into business and civil endeavors. Now in his 80’s, Sanders is still active and engaged in the law and business, enjoying life in a modern Georgia, he helped create. MUSIC Hoffman: Governor Sanders I’m so happy you’re here for this Conversation. Please know how much I appreciate your time. You have had a very distinguished career as a politician and as a lawyer and as a business man. -

Civil Rights Teacher Notes

One Stop Shop For Educators Arnall was born in Newnan, Georgia and received a law degree from the University of Georgia in 1931. Arnall’s career in politics began with his 1932 election to the Georgia General Assembly. Six years later he was appointed as the nation’s youngest attorney general at 31 years of age. In 1942, he defeated Eugene Talmadge, for governor. Arnall’s victory was largely due to the state’s university system losing its accreditation because of Talmadge’s interference (see Teacher Note SS8H9). As governor, Arnall is credited for restoring accreditation to the state’s institutions of higher learning, abolishing the poll tax, lowering the voting age, and establishing a teacher’s retirement system. However, Arnall lost support based on his support of liberal causes and leaders. One example was his acceptance of the Supreme Courts rulings against the white primary. He also lost popularity when he wrote two books that many southerners felt disparaged the South. Due to Georgia law, Arnall could not run for another term in 1947. He played a key role in the “three governor’s controversy” by refusing to give up the governor’s office until the issue was worked out (see Teacher Note SS8H11). Though a strong candidate for Governor in 1966, Arnall lost to segregationist Lester Maddox. He never ran for office again. After this election, Arnall was a successful business man and lawyer until his death. For more information about Ellis Arnall and his impact on the state see: The New Georgia Encyclopedia: “Ellis Arnall” http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-597&hl=y Sample Question for H10a (OAS Database) Sample Question for H10c After World War II in the United States, which of these trends Which Georgia governor receives credit for these accomplishments contributed to the growth of Georgia? • Restoring accreditation to Georgia’s university system A. -

'64 Graduating Class to Hear Ernest Vandiver, Rev. Carruth

SUPPORT EAGLES IN AREA 7 TOURNEY Published by the Students of Georgia Southern College Volume 37 STATESBORO, GEORGIA, FRIDAY, MAY 22, 1964 NUMBER 28 ’64 Graduating Class To Hear Ernest Vandiver, Rev. Carruth SPRING QUARTER Baccalaureate, Commencement Examination Schedule May 30 - June 4 The place of the examina- Programs Scheduled June 7 tion is the regular meeting place of the class unless other- The Rev. Edward H. Carruth, pastor of the Porterfield Me- wise announced by the instruc- morial Methodist Church of Albany, and former Gov. Ernest tor. Vandiver will address Georgia Southern graduates at the Bacca- Saturday, May 30—8 a.m., laureate and Commencement exercises on Sunday, June 7. All 1st period classes; 1 p.m., Dr. Zach S. Henderson, presi-1 Emory University following work All 9th period casses. dent of GSC, announced this in the School of Architecture at Monday, June 1—8 a.m., All week that the Rev. Carruth the Georgia Institute of Tech- 2nd period classes; 1 p.m., All will speak at the Baccalaureate nology. 8th period casses. program which will take place at Reverend Carruth was ordain- Tuesday, June 2—8 a.m., All 11 a.m. Vandiver will speak at ed as a Methodist Minister in 3rd period classes; 1 p.m., All the Commencement program 1942 and served in the United 7th period classes. which will get under way at States Naval Chaplain Corps Wednesday, June 3—8 a.m., 3:30 p.m. during World War II. All 4th period classes; 1 p.m., Prior to his appointment as All 6th period classes. -

State and Territorial Officers

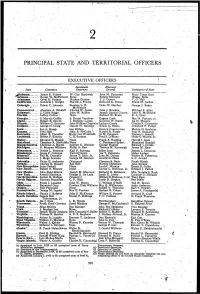

r Mf-.. 2 PRINCIPAL STATE AND TERRITORIAL OFFICERS EXECUTIVE- OFFICERS • . \. Lieutenant Attorneys - Siaie Governors Governors General Secretaries of State ^labama James E. Folsom W. Guy Hardwick John M. Patterson Mary Texas Hurt /Tu-izona. •. Ernest W. McFarland None Robert Morrison Wesley Bolin Arkansas •. Orval E. Faubus Nathan Gordon T.J.Gentry C.G.Hall .California Goodwin J. Knight Harold J. Powers Edmund G. Brown Frank M. Jordan Colorajlo Edwin C. Johnson Stephen L. R. Duke W. Dunbar George J. Baker * McNichols Connecticut... Abraham A. Ribidoff Charles W. Jewett John J. Bracken Mildred P. Allen Delaware J. Caleb Boggs John W. Rollins Joseph Donald Craven John N. McDowell Florida LeRoy Collins <'• - None Richaid W. Ervin R.A.Gray Georgia S, Marvin Griffin S. Ernest Vandiver Eugene Cook Ben W. Fortson, Jr. Idaho Robert E. Smylie J. Berkeley Larseri • Graydon W. Smith Ira H. Masters Illlnoia ). William G. Stratton John William Chapman Latham Castle Charles F. Carpentier Indiana George N. Craig Harold W. Handlpy Edwin K. Steers Crawford F.Parker Iowa Leo A. Hoegh Leo Elthon i, . Dayton Countryman Melvin D. Synhorst Kansas. Fred Hall • John B. McCuish ^\ Harold R. Fatzer Paul R. Shanahan Kentucky Albert B. Chandler Harry Lee Waterfield Jo M. Ferguson Thelma L. Stovall Louisiana., i... Robert F. Kennon C. E. Barham FredS. LeBlanc Wade 0. Martin, Jr. Maine.. Edmund S. Muskie None Frank Fi Harding Harold I. Goss Maryland...;.. Theodore R. McKeldinNone C. Ferdinand Siybert Blanchard Randall Massachusetts. Christian A. Herter Sumner G. Whittier George Fingold Edward J. Cronin'/ JVflchiitan G. Mennen Williams Pliilip A. Hart Thomas M. -

Activity : Responses to the Civil Rights Movement Possible Responses Include

0 1 / / E d u c a t o r R e s o u r c e A C T I V I T Y : R E S P O N S E S TO T H E C I V I L R I G H T S A C T INSTRUCTIONS Below are four different responses from Georgians to the passage of the Civil Rights Acts of 1964. This activity asks students to paraphrase and condense the main arguments in each of the responses down to one sentence. When completed students should get into small groups of 2-4 and compare their paraphrased sentences.Did they agree upon the main points of each of the original responses? If not, they should work together to further condense their individual sentences into a single group sentence for each response. The activity can conclude with a general classroom discussion about the main arguments in each of the responses and what explains the different ways Georgians responded to the Civil Rights Act. Letter from Anne Penn to Rose Levin, n.d. [c. 1964] Anne Penn was a 31-year-old African American woman from Rome, Georgia. In this letter to her former employer Rose Levin, she discusses the situation in Rome following the passage of the Civil Rights Act. Since the Civil Rights Bill have been signed this place have been in a mess and I am not ashamed to say I am scared. Maybe not for me so much but for my children, its not even safe for them to walk along the streets. -

Turning the Tide in the Civil Rights Revolution: Elbert Tuttle and the Desegregation of the University of Georgia

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 5 1999 Turning the Tide in the Civil Rights Revolution: Elbert Tuttle and the Desegregation of the University of Georgia Anne S. Emanuel Georgia State University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Education Law Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Legal Biography Commons Recommended Citation Anne S. Emanuel, Turning the Tide in the Civil Rights Revolution: Elbert Tuttle and the Desegregation of the University of Georgia, 5 MICH. J. RACE & L. 1 (1999). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol5/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TURNING THE TIDE IN THE CIVIL RIGHTS REVOLUTION: ELBERT TUTTLE AND THE DESEGREGATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA Anne S. Emanuel* Truth is sometimes stranger than fiction. So it was in 1960 when Elbert Tuttle became the Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, the federal appellate court with jurisdiction over most of the Deep South. Part of the genius of the Republic lies in the carefully calibrated structure of the federal courts of appeal. One assumption underlying the structure is that judges from a particular state might bear an allegiance to the interests of that state, which would be reflected in their opinions.