Interview with Mr John Moreland: Audio Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consigue Que Todos Tus Clientes Quieran Postre

Consigue que todos tus clientes quieran postre. Te ayudamos a preparar y vender mejor tus postres de carta, menú y delivery & take away, aumentando tu tiquet medio. Descubre nuestros productos y compra online en ufs.com Pablo García Chef Unilever Food Solutions [email protected] CARTA Una solución dulce para cada negocio. Hoy, sabemos de primera mano que tienes el foco puesto en salir adelante y poder adaptar tu oferta a las nuevos canales como el delivery & take away, sin desatender las necesidades en sala. MENÚ Replantear tus postres, de forma ágil y efectiva, será la forma de aumentar el tique medio y asegurar que cumples con los objetivos de tu restaurante en tiempo récord. Por eso te presentamos una amplia gama de postres, recetas e inspiración, en clave control de costes y fáciles de preparar, que sorprenderán a tus clientes tanto en el menú diario, como en la carta o a domicilio. 2 3 DELIVERY Los postres, la parte más 6 rentable de tu oferta La importancia de los postres en la rentabilidad de tu negocio.................................7 La rentabilidad de los postres en el menú ...................................................................................8 La rentabilidad de los postres en la carta ....................................................................................9 Postres de menú 10 La decoración, tu aliado para seducir .............................................................................................11 ¡Multiplica tu oferta de postres de forma fácil! .........................................................................12 -

Useandcare&' Cookin~ Guid&;

UseandCare&’ Cookin~ Guid&; Countertop Microwave Oven Contents Adapter Plugs 32 Hold Time 8 Add 30 Seconds 9 Important Phone Numbers 35 Appliance Registration 2 Instigation 32 Auto Defrost 14, 15 Light Bulb Replacement 31 Auto Roast 12, 13 Microwaving Tips 3 Auto Simmer 13 Minute/Second Timer 8 Care and Cleaning 31 Model and Serial Numbers 2,6 Consumer Services 35 Popcorn 16 Control Panel 6,7 Power Levels 8-10 Cooking by Time 9 Precautions 2 Cooking Complete Reminder 6 Problem Solver 33 Cooking Guide 23-29 ProWarn Cooking 5,7 Defrosting by Time 10 Quick Reheat 16 Detiosting Guide 21,22 Safety Instructions 3-5 Delayed Cooting Temperature Cook 11 Double Duty Shelf 5,6,17,30, 3? Temperature Probe 4,6, 11–13, 31 Express Cook Feature 9 WaKdnty Back Cover Extension Cords 32 Features 6 CooHng Gtide 23-29 Glossary of Microwave Terms 17 Grounding Instructions 32 GE Answer Center@ Heating or Reheating Guide 19,20 800.626.2000 ModelJE1456L Microwave power output of this oven is 900 watts. IEC-705 Test Procedure GE Appliances Help us help you... Before using your oven, This appliance must be registered. NEXT, if you are still not pleased, read this book carefully. Please be certtin that it is. write all the details—including your phone number—to: It is intended to help you operate Write to: and maintain your new microwave GE Appliances Manager, Consumer Relations oven properly. Range Product Service GE Appliances Appliance Park Appliance Park Keep it handy for answers to your Louisville, KY 40225 questions. Louisville, KY 40225 FINALLY, if your problem is still If you don’t understand something If you received a not resolved, write: or need more help, write (include your phone number): damaged oven.. -

Guardian and Observer Editorial

guardian.co.uk/guides Welcome | 3 Dan Lepard 12 • Before you start 8 Yes, it’s true, baking is back. And • Meet the baker 12 whether you’re a novice pastry • Bread recipes 13 • Cake 41 roller or an expert icer, our • Pastry 69 scrumptious 100-page guide will • Baking supplies 96 take your enjoyment of this relaxing and (mostly) healthy pursuit to a whole new level. We’ve included the most mouthwatering bread, cake and pastry recipes, courtesy of our Tom Jaine 14 baking maestro Dan Lepard and a supporting cast of passionate home bakers and chefs from Rick Stein and Marguerite Patten to Ronnie Corbett and Neneh Cherry. And if Andi and Neneh 42 you’re hungry for more, don’t miss tomorrow’s Observer supplement on baking with kids, and G2’s exclusive series of gourmet cake recipes all next week. Now get Ian Jack 70 KATINKA HERBERT, TALKBACK TV, NOEL MURPHY your pinny on! Editor Emily Mann Executive editor Becky Gardiner All recipes by Dan Lepard © 2007 Additional editing David Whitehouse Recipe testing Carol Brough Art director Gavin Brammall Designer Keith Baker Photography Jill Mead Picture editor Marissa Keating Production editor Pas Paschali Subeditor Patrick Keneally Staff writer Carlene Thomas-Bailey Production Steve Coady Series editor Mike Herd Project manager Darren Gavigan Imaging GNM Imaging Printer Quebecor World Testers Kate Abbott, Keith Baker, Diana Brown, Nell Card, Jill Chisholm, Charlotte Clark, Margaret Gardner, Sarah Gardner, Barbara Griggs, Liz Johns, Marissa Keating, Patrick Keneally, Adam Newey, Helen Ochyra, Joanna Rodell, John Timmins, Ian Whiteley Cover photograph Alexander Kent Woodcut illustration janeillustration.co.uk If you have any comments about this guide, please email [email protected] To order additional copies of this Guardian Guide To.. -

Bakery & Café Hours

March Menu begins Monday, March 1, 2021 Bakery & Café Hours Monday — Saturday 10am-4pm Closed Sundays 513-321-3399 • 2030 Madison Road, Cincinnati, OH 45208 Party Cakes & Tortes 6” serves 6-10, 9” serves 14-20 Opera Cream Our signature cake for over thirty years. This double chocolate chip cake is filled and iced with our rich vanilla Opera Cream filling, then enrobed with a rich chocolate marquis glaze and decorated with Belgian dark chocolate, buttercream rosettes, and white chocolate diamonds. $4.75 a slice · $28 for 6” · $52 for 9” Carrot Cake Our carrot cake adheres to what we think is the best version of a classic. Pure and simple, the cake itself is made with fresh carrots. We fill and frost it with our cream cheese frosting while we generously coat the sides with fresh walnuts and finish it with a pinch of cinnamon. $4.75 a slice · $26 for 6” · $44 for 9” Raspberry Chantilly Torte Nothing says “special party” like berries and cream. Each layer of our deli- cate chiffon cake is filled with a whipped cream and white chocolate filling combined with bright raspberry puree. The torte is covered in white choco- late buttercream and decorated in sugar flowers. $4.75 a slice · $28 for 6” · $52 for 9” Heavenly Mint Torte Delicate, freshly whipped mint cream fills and surrounds three layers of our moist chocolate cake. We coat the outside with chocolate cookie crumbs, cover the top with dark chocolate glaze, and decorate it with handmade pieces. It’s like biting your favorite chocolate mint cookie. -

The Little French Bakery Cookbook Sweet & Savory Recipes and Tales from a Pastry Chef and Her Cooking School

The Little French Bakery Cookbook SWEET & SAVORY RECIPES AND TALES FROM A PASTRY CHEF AND HER COOKING SCHOOL Susan Holding Skyhorse Publishing CONTENTS Chapter One – Let’s Get Started Meet Susan xx Story: My First Days in Paris xx Equipment for Your Kitchen xx Kitchen Set-up xx Story: Using a scale at School xx Weights and Temperature Conversion Chart xx Chapter Two – Must Have Recipes and Techniques How and Why to Caramelize Onions xx Slicing for Caramelized Perfection xx Why do you need them? xx Tart Crust xx Story: Basic Pastry Final Exam xx Perfect Cheese Course xx How to Make Great Stock xx Crème Fraîche xx Oven Roasted Cherry Tomatoes xx Poached Pears and Tinned Fruits xx Vanilla Beans xx Nutmeg – That certain “Je ne sais quoi” xx Chapter Three – Appetizers and Starter Courses Baked Goat Cheese Salad xx Caramelized French Onion Dip xx Summer Mango Salsa xx Quick Cheese Crackers xx Goat Cheese Butter and Radishes xx Sun Dried Tomato Torta xx Puff Pastry Salmon Puffs xx Warm Olives xx Sacristain (Puff Pastry Sticks) xx Story: My Dad’s Favorite Dessert xx Spicy in the Pan Shrimp xx Strawberry Mousse Cake (Charlotte) xx Story: My First Big Dinner Party xx Tiramisu xx Mussels with Garlic and White Wine xx English Trifle xx Story: Let’s Forget Dinner and Eat Mussels xx Desert Sand Sponge Cake (Victoria) xx Story: Every Christmas Eve xx Chapter Four – Breads Lemon Cheesecake with Fresh Berries xx Farmhouse White xx Story: My Very First Cheesecake and Fancy Mixer xx Story: My First Bread xx Profiteroles xx Baguettes xx Tart Tatin xx Story: -

Italian Family Style Service

ClubTRADITIONAL ItalianLucky FOOD Family Style Service COCKTAIL LOUNGE ! Thank you for considering Club Lucky for your special event. Enclosed you will find some samples of our Family Style menus or our management staff can help you choose from our extensive main menu. There are many options available to suit your palate as well as your budget. We suggest a meal consisting of an Appetizer, Salad, Pasta Entrée, House Specialty Entree and Dessert. However we will make every effort to honor any request you may have or customize a menu for your special event. Club Lucky is Bucktown/Wicker Park’s most popular restaurant specializing in Traditional Italian food served family style. The design is that of a 1940’s supper club, a unique cocktail lounge, two outdoor patios, and a private dining room on the verge of the 1950’s. From the antique martini shaker collection to the oversized tables and booths and the warm lighting you and your guests will feel right at home. The atmosphere is casual, portions are generous and the prices are reasonable. We can accommodate parties up to 20-45 in our private room (The Club Room), from 130-250 in our main dining room, and up to 70 in our unique cocktail lounge. If you are planning your next event at your home or business office, let us cater your special occasion with party sized pans that can accommodate any amount of guests. If you are planning a lunch or dinner event in the Chicago area, Club Lucky is the perfect place. Our easy access off the Kennedy Expressway (only 5 blocks west on North Ave.) is just minutes from the Loop & Downtown Hotels. -

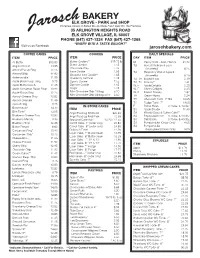

Jarosch Menu Oct 2020

BAKERY ELK GROVE - PARK and SHOP Complete Variety of Baked Goods Made Fresh Daily On The Premises 35 ARLINGTON HEIGHTS ROAD ELK GROVE VILLAGE, IL 60007 PHONE (847) 437-1234 FAX (847) 437-1268 “EVERY BITE A TASTE DELIGHT” Visit us on Facebook jaroschbakery.com COFFEE CAKES COOKIES DAILY SPECIALS ITEM PRICE ITEM PRICE DAY ITEM PRICE All Butter $10.90 Butter Cookies** $19.75 lb M Pastry Stick - Asst. Flavors $1.72 Alligator Pecan 14.55 Butter Jumble 1.15 TU Apricot Graham 6 pack Chocolate Chip 1.15 Almond Pecan Ring 12.25 (bi-weekly) 8.25 Face Cookie 1.65 TU Raspberry Walnut 6 pack Almond Strip 11.90 Seasonal Iced Cookie** 1.65 (bi-weekly) 8.25 Andersonville* 11.95 Cranberry Oatmeal 1.15 TU, TH Elephant Ear 2.19 Apple Black Rasp. Ring 9.75 Sports Cookie* 2.55 TU, TH Kolacky** 1.31 Apple Butterscotch 11.45 Sprinkle Cookie 1.15 W, F Apple Delights 2.25 Apple Cinnamon Raisin Ring* 10.90 Sugar 1.15 W, F Cherry Delights 2.25 Apple-Raisin Strip 12.25 Mini Chocolate Chip 24/bag 5.20 W, F French Donuts 1.82 Mini Chocolate Chip 24/bag w/cc 2.60 Apricot-Cheese Strip 10.80 TH Cream Horns 2.24 Apricot Crescent 11.45 TH Chocolate Torte- 7” BC 19.65 TH Fudge Torte- 7” 19.65 Apricot Ring 9.75 IN-STORE CAKES F Donut Holes 0.45/ea 5.40/doz Bienenstuck* 14.10 ITEM PRICE SA Apple Strudel 10.40 Blitz Torte* 13.05 Angel Food Lg Rnd Iced $20.30 SA Weekly Special Coffee Cake** Blueberry-Cheese Strip 10.80 Angel Food Lg Rnd Plain 12.65 SA Poppyseed Horn 0.70/ea, 8.40/doz Blueberry Melody 9.95 Seasonal Cake Roll** 10.20 / 12.50 SA Salt Sticks 0.70/ea, 8.40/doz Blueberry -

Jarosch-Bakery-Price-List-2017-3

sch BAKERY aro ELK GROVE - PARK and SHOP J Complete Variety of Baked Goods Made Fresh Daily On The Premises 35 ARLINGTON HEIGHTS ROAD ELK GROVE VILLAGE, IL 60007 PHONE (847) 437-1234 FAX (847) 437-1268 Visit us on Facebook “EVERY BITE A TASTE DELIGHT” jaroschbakery.com COFFEE CAKES COOKIES DAILY SPECIALS ITEM PRICE DAY ITEM PRICE ITEM PRICE Butter Cookies $18.95 lb All Butter $9.75 M Pastry Stick - Asst. Flavors $1.50 Butter Jumble 1.00 TU Apricot Graham (bi-weekly) 1.39 Alligator Pecan 13.20 Chocolate Chip 1.00 Almond Pecan Ring 11.00 TU, TH Elephant Ear 1.82 Face Cookie 1.50 TU, TH Kolacky 1.20 Almond Strip 10.65 Flower Power Cookie* 2.30 Apple Black Rasp. Ring 8.90 W, F Apple Delights 1.93 Oatmeal Raisin 1.00 W, F Cherry Delights 1.93 Apple Butterscotch 10.30 Sports Cookie* 2.30 Apple Cinnamon Raisin Ring* 9.75 W, F French Donuts 1.62 Sprinkle Cookie 1.00 TH Cream Horns 1.92 Apple-Raisin Strip 11.00 Sugar 1.00 TH Chocolate Torte- 7” 17.60 Apricot-Cheese Strip 9.70 Mini Chocolate Chip 24/bag 4.68 TH Fudge Torte- 7” 17.60 Apricot Crescent 9.75 Mini Chocolate Chip 24/bag w/cc 2.34 TH White Choc. Mousse Torte- 7” 17.60 Apricot Ring 8.90 Mini Oatmeal 24/bag 4.68 TH Raspberry Walnut 1.39 Bienenstuck* 12.70 Mini Oatmeal 24/bag w/cc 2.34 Blitz Torte* 11.65 F Donut Holes 0.40ea 4.80doz Blueberry Melody 8.95 SA Apple Strudel 9.30 Blueberry-Cheese Strip 9.70 SA Weekly Special Coffee Cake** Blueberry Strip 11.00 IN-STORE CAKES SA Poppyseed Horns 0.62ea 7.44doz Butter Pretzel 7.70 ITEM PRICE SA Salt Sticks 0.62ea 7.44doz Caramel Pecan Loaf 12.70 -

Menú Niños Desserts

Dinner - Cena 2 Kids Menu - Menú Niños 7 Desserts - Postres 8 Drinks - Bebidas 9 Wine List - Lista de Vinos 11 A little something to munch on Algo para picar... Enjoy an array of traditional appetizers hailing all the way from the northern regions of Mexico to the south. This is the beginning of a culinary journey through the time-honored recipes of Mexican cuisine Disfruta de una amplia selección de entrantes, cuya variedad pertenece a regiones del norte al sur del país. Este es el inicio de un viaje culinario a través de la cocina ancestral mexicana GUACAMOLE ARTESANAL Fresh mint scented guacamole, chili, green tomato and grasshoppers Guacamole aromatizado con hierbabuena, chile piquín, tomate y chapulín CEVICHE DEL MAR DE CORTEZ TATEMADO Chili crust catch of the day, avocado, tomatoes, coriander and grilled onions, sprinkle with chili oil and lime Pesca del día en costra de chiles, aguacate, tomates, cilantro, cebollas tatemadas en aceite de chile de árbol y limón LA COLORADITA Beet and ricotta cheese salad topped with crispy corn Ensalada de remolacha y requesón con crujiente de maíz Mild · Poco picante Spicy · Picante Hot · Muy Picante Vegan · Vegano 2 And now something a bit warmer Y ahora algo calientito CRUJIENTE DE COTIJA Pulled beef with blue corn, sweet peas and crispy cheese Carne mechada de res con maíz azul, chícharos y queso crujiente FRITOS DE CHIAPAS Deep fried plantain stuffed with fresh spicy cheese and cumin sauce Plátano macho frito relleno de queso fresco picante con salsa de comino Traditional Mexican broths Caldos -

Summer-2019-Canada-Spreads.Pdf

SUMMER 2019 Rise and Dine BURGERS+ WITHOUT BOUNDARIES /P.20 DECADENT SUMMER DESSERTS /P.2 4 A FRESH LOOK AT FOOD WASTE /P.11 HOLIDAY PREP CHECKLIST /P.27 Hatch Chile Crab Cake Wafflewich With Green Tomato Fries Page 12 IN THIS ISSUE Summer Haze Burger With Lemon-Thyme Fries; FROM OCEAN TO PLATE article on page 20. Message From the IN RECORD TIME. Executive Editor Dear Valued Sysco Customer, Welcome to our Big Breakfast Issue! We are excited to dive into both the culinary and operations sides of this delicious and profitable daypart. To see what’s hot in breakfast service across Canada and the U.S., go to our regional trend map on page 16. For tips, insights and inspiration on how to grow your breakfast operation, see our feature story on page 12. And DEPARTMENTS get the latest on Sysco’s versatile packaging for 2 WORLD OF SYSCO on-the-go breakfast (or any meal) on page 18. Learn how Sysco’s fresh dairy maintains the highest safety standards See what’s big with in the industry and why Cargill has been our primary ground beef premium burgers, from supplier for more than 15 years. Discover Citavo premium coffees and grass-fed patties to read about a restaurant with top seafood and a pristine view. distinctive buns (page 9 CULINARY TRENDS 20). And don’t forget Get expert tips on how to measure and manage food waste, and learn the sides: See our how to add profit to your french fry plate. suggestions for adding interesting spices, 27 OPERATIONS sauces and dips to Find the tools and inspiration you need to do grab-and-go breakfast Dominic Iezzi french fries as a way to right. -

17 Century Maison

Tel London: +44 208 961 6770 www.parisrentalconnections.com Email: [email protected] 14/02/2019 17 Century Maison 36 rue Vieille du Temple 75004 Entrance Code: 13698 then bell button Through glass door on the left 5th floor left door marked Friedman Telephone: 01 77 18 30 85 Metro: Hotel de Ville or St Paul 17th Century Maison is ideally located in the Marais, an area considered as one of Paris’ “quartiers branchés”-hip neighbourhoods with its many trendy boutiques, cafés and restaurants and home to the Musée Carnavalet (Paris history museum) and the Place Vosges the beautiful royal square constructed under Henri IV in 1605. The street owes it’s name to the knights of the round temple (the Templiers) who first gathered in what is now called the Rue Vieille du Temple which is filled with great boutiques and great food shops. Here you’ll find everything from bread & pastries and chocolate to the funky and refined in home furnishings. From the apartment walk towards rue de Rivoli to view the majestic Hotel de Ville (Town hall) and Notre Dame on the Ile de la Cité and explore the neighbourhoods of the Latin Quarter and St Germain. Walking North you arrive at the Centre George Pompidou, one of Paris’ most controversial architectural projects and home to the museum of modern art and many avant-garde temporary exhibitions. Cross the blvd Sébastopol, for les Halles, once the location of Paris’ main food markets from the 12th century to the 1960’s when the market and the merchants were moved out and the site converted into a large pedestrian area with a huge underground shopping mall, the Forum des Halles. -

Nuestros Postres

NUESTROS POSTRES PAN DULCE MINIATURA ∙ PIES CHEESECAKES ∙ PASTELES OTROS POSTRES PIES PASTEL DE ZANAHORIA $3.75 PIE DE MANZANA $2.75 Triple torta, doble relleno Entero (8 porciones) $18.00 Entero (12 porciones) $38.00 PIE DE HIGO $2.75 BROWNIE AFFOGATO $3.75 Entero (8 porciones) $18.00 Dos porciones de brownie clásico con una bola de sorbete de vainilla, bañado en PIE DE CEREZAS CON QUESO $3.00 Bailey’s Espresso Creme. (contiene licor) Entero (8 porciones) $20.00 BROWNIE CON NUECES $2.50 PIE DE GUAYABA CON QUESO $3.00 Entero (8 porciones) $18.00 Entero (8 porciones) $20.00 TIRAMISÚ IN A CUP $2.75 PIE DE NUTELLA CON QUESO $3.50 Entero (8 porciones) $26.00 TRES LECHES IN A CUP $2.75 TRES LECHES CON BAILEY’S $3.25 PIE DE LIMÓN $3.00 Tres leches in a cup bañado en Entero (8 porciones) $20.00 Bailey’s Irish Cream. (contiene licor) TARTA DE NUECES $3.50 Mezcla de cuatro semillas: pecanas, almendras, macadamias y walnuts. BIZCOCHOS Entero (8 porciones) $26.00 BIZCOCHO DE ZANAHORIA $8.50 BIZCOCHO DE BANANO $8.50 CHEESECAKES BIZCOCHO ROLL BETÚN DE QUESO Y PECANAS $. CHEESECAKE DE LA CHITA CON FRESAS $3.50 Entero (12 porciones) $35.00 BIZCOCHO ROLL CARAMELO SALADO Y PECANAS $. OREO CHEESECAKE $3.75 Entero (12 porciones) $38.00 BIZCOCHO ROLL TRIPLE CHOCOLATE $. BROWNIE CHEESECAKE $3.75 Entero (12 porciones) $38.00 DE TEMPORADA SALTED CARAMEL & PECAN CHEESECAKE $3.75 BUDÍN DE CIRUELA Y CREMA $2.75 Entero (12 porciones) $40.00 Entero (10 porciones) $22.00 (Consulte disponibilidad) BACON CARAMEL CHEESECAKE $3.75 Entero (12 porciones) $38.00 PIE DE MANGO $3.00 Entero (8 porciones) $20.00 CHEESECAKE CON SEMILLA DE MARAÑÓN (Disponible solo en temporada) Y BAILEY’S $4.00 BIZCOCHO DE CALABAZA $3.50 Bañado con Bailey’s Irish Cream Original.