A Comparative Analysis of Free Trade Between the US and the EU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 ITTF EVENTS CALENDAR Updated 2015.06.21

2015 ITTF EVENTS CALENDAR updated 2015.06.21 DATE DAYS EVENT LOCATION 2015 ITTF EVENTS JANUARY 8 to 11 Thu - Sun World Team Cup Dubai / UAE 23 to 29 Fri-Thu ITTF-African Senior Championships Cairo / EGY 28 to 1 Febr Wed-Sun GAC Group World Tour, Hungarian Open - Challenge Series Budapest / HUN 29 to 31 Thu-Sat 2014 Global Junior Circuit Finals Asuncion / PAR FEBRUARY 3 to 7 Tue-Sat Bahrain Junior & Cadet Open, ITTF Premium Junior Circuit Manama / BRN 6 to 8 Fri-Sun ITTF-European TOP 16 Cup Baku / AZE 11 to 15 Wed-Sun Czech Junior & Cadet Open, ITTF Premium Junior Circuit Hodonin / CZE 11 to 15 Wed-Sun GAC Group World Tour, Kuwait Open - Super Series Kuwait City / KUW 17 to 22 Tue-Sun GAC Group World Tour, Qatar Open - Super Series Doha / QAT 18 to 22 Wed-Sun Swedish Junior & Cadet Open, ITTF Junior Circuit Orebro / SWE 28 to 3 March Sat-Tue Paraguay Junior & Cadet Open, ITTF Junior Circuit Asuncion / Paraguay MARCH 4 to 8 Wed-Sun Italian Junior & Cadet Open, ITTF Premium Junior Circuit Lignano / ITA 10 to 14 Tue-Sat GAC Group World Tour, Nigeria Open - Challenge Series Lagos / NGR 16 to 24 Mon-Tue ITTF-Latin American Championships/Panam Games Qualification Buenos Aires / ARG 18 to 22 Wed-Sun GAC Group World Tour, German Open - Super Series Bremen / GER 22 to 26 Sun-Thu Tunisia Junior & Cadet Open, ITTF Junior Circuit Monastir / TUN 25 to 29 Wed-Sun GAC Group World Tour, Spanish Open - Major Series Almeria / ESP APRIL 1 to 5 Wed-Sun Belgium Junior & Cadet Open, ITTF Junior Circuit Spa / BEL 3 to 6 Fri-Mon Australian Junior & Cadet Open, -

Pgasrs2.Chp:Corel VENTURA

Senior PGA Championship RecordBernhard Langer BERNHARD LANGER Year Place Score To Par 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Money 2008 2 288 +8 71 71 70 76 $216,000.00 ELIGIBILITY CODE: 3, 8, 10, 20 2009 T-17 284 +4 68 70 73 73 $24,000.00 Totals: Strokes Avg To Par 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Money ê Birth Date: Aug. 27, 1957 572 71.50 +12 69.5 70.5 71.5 74.5 $240,000.00 ê Birthplace: Anhausen, Germany êLanger has participated in two championships, playing eight rounds of golf. He has finished in the Top-3 one time, the Top-5 one time, the ê Age: 52 Ht.: 5’ 9" Wt.: 155 Top-10 one time, and the Top-25 two times, making two cuts. Rounds ê Home: Boca Raton, Fla. in 60s: one; Rounds under par: one; Rounds at par: two; Rounds over par: five. ê Turned Professional: 1972 êLowest Championship Score: 68 Highest Championship Score: 76 ê Joined PGA Tour: 1984 ê PGA Tour Playoff Record: 1-2 ê Joined Champions Tour: 2007 2010 Champions Tour RecordBernhard Langer ê Champions Tour Playoff Record: 2-0 Tournament Place To Par Score 1st 2nd 3rd Money ê Mitsubishi Elec. T-9 -12 204 68 68 68 $58,500.00 Joined PGA European Tour: 1976 ACE Group Classic T-4 -8 208 73 66 69 $86,400.00 PGA European Tour Playoff Record:8-6-2 Allianz Champ. Win -17 199 67 65 67 $255,000.00 Playoff: Beat John Cook with a eagle on first extra hole PGA Tour Victories: 3 - 1985 Sea Pines Heritage Classic, Masters, Toshiba Classic T-17 -6 207 70 72 65 $22,057.50 1993 Masters Cap Cana Champ. -

Chile-Indonesia Joint Study Group on the Feasibility of a Free Trade Agreement: Final Report

CHILE-INDONESIA JOINT STUDY GROUP ON THE FEASIBILITY OF A FREE TRADE AGREEMENT: FINAL REPORT This study was prepared by the General Directorate of International Economic Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Chile and Ministry of Trade, Republic of Indonesia Bali, Indonesia, November 11-12, 2009 Chile-Indonesia Joint Study Group on the Feasibility of a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) Chile-Indonesia Joint Study Group on the Feasibility of a Free Trade Agreement CHILE-INDONESIA JOINT STUDY GROUP ON THE FEASIBILITY OF A FREE TRADE AGREEMENT: FINAL REPORT Bali, Indonesia, November 11-12, 2009 2 Chile-Indonesia Joint Study Group on the Feasibility of a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) Executive Summary Indonesia and Chile had agreed in November 2008 to conduct a joint study group on the merits of a bilateral free trade agreement. Both countries agreed that the study would be completed by early 2010, with recommendations for their political authorities. The bilateral relationship has developed considerably in recent years, such as the establishment of a Joint Commission reflecting the shared commitment of the two countries to advance cooperation on a wide range of bilateral and regional interests. Indonesia and Chile have worked closely and they are willing to expand further its relationship given the importance of the two nations in the Southeast Asia and Latin America region. Indonesia the largest economy in ASEAN and the world’s fourth most populous nation, and Chile one of the most developed economies in the Latin America region. Despite of trade potentials, trading relationship between two countries is still very limited. -

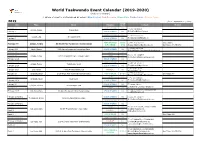

World Taekwondo Event Calendar (2019-2020)

World Taekwondo Event Calendar (2019-2020) (subject to change) ※ Grade of event is distinguished by colour: Blue-Kyorugi, Red-Poomsae, Green-Para, Purple-Junior, Orange-Team 2019 (as of September 17, 2019) Event Date Place Event Discpline Contacts Remark Grade February 1-2 CADET & JUNIOR N/A (T) +357 99 443551 Larnaka, Cyprus Cyprus Open February 3 SENIOR KYORUGI G-1 (E) [email protected] February 1-2 CADET & JUNIOR N/A (T) +971 556022230 Fujairah, UAE 7th Fujairah Open February 3 SENIOR KYORUGI G-1 (E) [email protected] PARA KYORUGI G-10/ (T) +41 21 601 50 13 (PSS: Daedo) February 5-6 Antalya, Turkey 8th World Para-Taekwondo Championships & POOMSAE G-10 (E) [email protected] Sport Class: K40/P30/P20 (T) +2348059001864 February 8-10 Abuja, Nigeria 2019 Nigeria Taekwondo International Open SENIOR KYORUGI G-1 (E) [email protected] February 7-8 CADET N/A (T) +30 211 214 4717 February 9-10 Antalya, Turkey 4th WT President's Cup - European region JUNIOR N/A (E) [email protected] February 11-12 SENIOR KYORUGI G-2 February 13-14 CADET & JUNIOR N/A (T) +90 530 575 27 00 Antalya, Turkey Turkish Open 2019 February 15-16 SENIOR KYORUGI G-1 (E) [email protected] (T) +7 62 62 73 27 February 16-17 Lille, France French Poomsae Open 2019 POOMSAE G-1 (E) [email protected] (T) +41 21 601 50 13 February 20 Hurghada, Egypt 2019 African Para Taekwondo Championships PARA KYORUGI G-4/G-2 Sport Class: K40 (E) [email protected] February 21-22 CADET N/A (T) +2 122 3113155 Hurghada, Egypt Egypt Open -

ITTF Calendar Dates – 2016 (As of 5 July 2015)

ITTF Calendar Dates – 2016 (as of 5 July 2015) January 20 - 24 ITTF World Tour, Hungarian Open, Budapest (HUN) 22 - 24 2015 World Junior Circuit Finals (TBD) 27 - 31 ITTF World Tour, German Open, Berlin (GER) February 1 -7 ITTF-Latin American Championships, San Juan (PUR) 5 - 7 ITTF-Europe Cup, TOP 16, Gondomar (POR) 10 - 14 ITTF World Tour, Philippines Open, Manila (PHI) 14 - 15 ITTF-African Top 16 Cup, Khartoum (SUD) 16 - 18 ITTF-African Olympic Qualification, Khartoum (SUD) 28 - March 6 World Team Table Tennis Championships, Kuala Lumpur (MAS) March 16 - 20 ITTF World Tour, Kuwait Open, Kuwait City (KUW) 20 - 24 ITTF-Oceania Championships, Bendigo (AUS) 22 - 25 ITTF-Oceania Olympic Qualification, Bendigo (AUS) 23 - 27 ITTF World Tour, Qatar Open, Doha (QAT) April 1 - 3 ITTF-Latin American Olympic Qualification, Santiago de Chile (CHI) 6 - 12 ITTF-African Junior & Cadet Championships, Tiziozou (ALG) 6 - 10 ITTF-European Olympic Qualification, Istanbul (TUR) 8 - 10 ITTF-North American Olympic Qualification, Toronto-Markham (CAN) 13 - 17 ITTF-Asian Olympic Qualification, Hong Kong (HKG) 20-24 ITTF World Tour, Polish Open, Warsaw (POL) 28-30 ITTF-Asian Cup, Dubai (UAE) May 11 - 15 ITTF World Tour, Chile Open, Santiago (CHI) 18 - 22 ITTF World Tour, Nigeria Open, Lagos (NGR) 25 - 29 ITTF World Tour, Croatia (Zagreb) Open, Zagreb (CRO) June 1 - 5 ITTF World Tour, Slovenia Open, Otocec (SLO) 8 - 12 ITTF World Tour, Australian Open, Sydney (AUS) 15 - 19 ITTF World Tour, Japan Open, Tokyo (JPN) 22 - 26 ITTF World Tour, Korea Open, Incheon (KOR) -

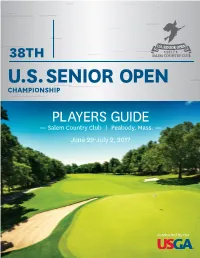

PLAYERS GUIDE — Salem Country Club | Peabody, Mass

38TH U.S. SENIOR OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP PLAYERS GUIDE — Salem Country Club | Peabody, Mass. — June 29-July 2, 2017 conducted by the 2017 U.S. SENIOR OPEN PLAYERS' GUIDE — 1 2017 U.S. Senior Open MICHAELhttp://www.golfstats.com/gs_scripts/golfstats/golfstats.php?guide=2017sopen&style=&tour=Champions&name=Michael+Allen&year=&tour ALLEN nament=&in=Search Exemption List (as of June 19) Birth Date: January 31, 1959 Michael Allen 9, 11, 18, 19 Tom Kite 19 Birthplace: San Mateo, Calif. Stephen Ames 19, 21, 22 Barry Lane 23 Billy Andrade 18, 19, 21, 22 Bernhard Langer 1, 2, 10, 11, 18, Age: 58 Ht.: 6’0" Wt.: 195 T. Armour III 18, 21 19, 21, 22 Magnus Atlevi 23 Tom Lehman 9, 11, 18, 19, 21, 22 Home: Scottsdale, Ariz. Woody Austin 17, 18, 19, 22, 25 Steve Lowery 19 College: Nevada Andre Bossert 23 a-Chip Lutz 13 Paul Broadhurst 10, 18, 22, 23 Jeff Maggert 1, 2, 18, 19, 22 Turned Professional: 1984 Olin Browne 1, 2, 18, 22 Prayad Marksaeng 24 Bart Bryant 18 Billy Mayfair 11, 19 Joined PGA Tour: 1990 Brad Bryant 1, 3 Scott McCarron 18, 21, 22 Tom Byrum 18 a-Mike McCoy 16 Joined Champions Tour: 2009 M. Calcavecchia 19, 22 Rocco Mediate 9, 18, 19, 22 Championshttp://www.golfstats.com/gs_scripts/golfstats/golfstats.php?guide=2017sopen&stat=31&name=Michael+Allen&tour=Champions Tour Playoff Record: 2-2 Roger Chapman 1, 2, 9 C. Montgomerie 1, 2, 9, 11, 18, 22 Fred Couples 19, 21, 22 Gil Morgan 19 Champions Tour Victories: 8 - 2009 Senior PGA John Cook 19 Mark O’Meara 19 Championship; 2012 Encompass Insurance Pro-Am, Liberty John Daly 21 Jesper Parnevik 18, 19, 22 Mutual Legends of Golf; 2013 Mississippi Gulf Resort Classic, Marco Dawson 10, 22 Corey Pavin 19, 26 Allen Doyle 3 Tom Pernice Jr. -

Education City Stadium Set to Host First Match

SPORT SPORT | 06 SPORT | 07 PL teams prepare Will saliva ban for restart with threaten practice games at Cricket's kings stadiums of swing? MONDAY 8 JUNE 2020 New Qatar 2022 venue to welcome teams for QSL action on July 24 Education City Stadium set to host first match RIZWAN REHMAT The completion of the state-of-the-art take on Umm Salal (4:45pm) THE PENINSULA stadium, which overlooks the picturesque while Al Shahaniya will battle Education City Golf Course, will be marked Al Ahli at Al Janoub Stadium Brand new Education City during a ceremony on June 15. and in the day’s final fixture, Al Stadium, a venue that will host Wakrah will play Al Sailiyah at the Qatar 2022 FIFA World Cup Jassim Bin Hamad Stadium matches, has been listed to (7:00pm). stage the first Qatar Stars The battle for points will League (QSL) match after resume next month with football activity was stalled in leaders Al Duhail (42 points the country to prevent the after 17 rounds), Al Rayyan (38), spread coronavirus pandemic Al Sadd (32) and Al Gharafa (28) in the middle of March. holding on to the top four slots According to the fixtures list in the 12-team league. announced by QSL yesterday, It may be noted that the Qatar SC will play their ‘home’ kick-off timings and venues of match against Al Rayyan on July matches in the last two weeks 24 at Education City Stadium (21 and 22) will be finalised later based on the results and QSL ROUND 17 FIXTURES standings of teams in the table, The venue has cooling technology that will allow as the QSL is keen to provide July 24 the match to be conducted in near-perfect playing all clubs with equal 4:45pm: Qatar SC vs Al Rayyan at conditions. -

View Document

INTERNATIONAL TABLE TENNIS FEDERATION AGM & BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING DOCUMENTS INDEX Annual General Meeting Agenda .......................................................................................... 3-4 Annual reports from the Executive Committee ................................................................. 5-26 President: Thomas Weikert ........................................................................................................... 5 Deputy President: Khalil Al-Mohannadi ....................................................................................... 8 Executive Vice President (Finance): Petra Sörling .................................................................... 10 Executive Vice President: Bruce Burton ................................................................................... 12 Executive Vice President: Patrick Gillmann ............................................................................... 15 Executive Vice President: Chérif Hajem .................................................................................... 17 Executive Vice President: Masahiro Maehara ........................................................................... 20 Executive Vice President: Melecio Eduardo Rivera ................................................................... 23 Executive Vice President: Shi Zhihao ........................................................................................ 25 Annual reports from the Continental Federations ......................................................... -

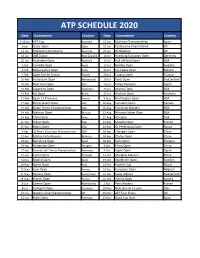

Atp Schedule 2020

ATP SCHEDULE 2020 Date Tournament Country Date Tournament Country 3-12-Jan ATP Cup Australia 22-Jun Mallorca Championships Spain 6-Jan Qatar Open Qatar 22-Jun Eastbourne International UK 13-Jan Adelaide International Australia 29-Jun Wimbledon UK 13-Jan ASB Classic New Zealand 13-Jul Hamburg European Open Germany 20-Jan Australian Open Australia 13-Jul Hall of Fame Open USA 3-Feb Cordoba Open Spain 13-Jul Nordea Open Sweden 3-Feb Maharashtra Open India 20-Jul Los Cabos Open Mexico 3-Feb Open Sud de France France 20-Jul Croatia Open Croatia 10-Feb Rotterdam Open Netherlands 20-Jul Swiss Open Switzerland 10-Feb New York Open USA 25-Jul Tokyo Olympics Japan 10-Feb Argentina Open Argentina 27-Jul Atlanta Open USA 16-Feb Rio Open Brazil 27-Jul Austrian Open Australia 17-Feb Open 13 Provence France 2-Aug Washington Open USA 17-Feb Delray Beach Open USA 10-Aug Canadian Open Canada 24-Feb Dubai Tennis Championships UAE 16-Aug Cincinnati Masters USA 24-Feb Mexican Open Mexico 23-Aug Winston-Salem Open USA 24-Feb Chile Open Chile 31-Aug US Open USA 12-Mar Indian Wells USA 21-Sep Moselle Open France 25-Mar Miami Open USA 21-Sep St. Petersburg Open Russia 6-Apr US Men's Clay Court Championships USA 28-Sep Chengdu Open China 12-Apr Monte Carlo Masters Monaco 28-Sep Zhuhai Open China 20-Apr Barcelona Open Spain 28-Sep Sofia Open Bulgaria 20-Apr Hungarian Open Hungary 5-Oct China Open China 27-Apr Bavarian Int'l Tennis Championships Germany 5-Oct Japan Open Japan 27-Apr Estoril Open Portugal 11-Oct Shanghai Masters China 3-May Madrid Open Spain 19-Oct Stockholm Open Sweden 10-May Italian Open Italy 19-Oct Kremlin Cup Russia 17-May Lyon Open France 19-Oct European Open Belgium 17-May Geneva Open Switzerland 26-Oct Swiss Indoors Switzerland 24-May French Open France 26-Oct Vienna Open Austria 8-Jun Libema Open Netherlands 2-Nov Paris Masters France 8-Jun Stuttgart Open Germany 10-Nov Next Gen ATP Finals Italy 15-Jun Queen's Club Championships UK 15-Nov ATP Tour Finals UK 15-Jun Halle Open Germany 23-Nov Davis Cup final Spain. -

Atp Tour2020 Season

ATP TOUR 2020 SEASON As of 2 December 2019 WEEK START DATE CITY TOURNAMENT NAME SURFACE DRAW 1 3 JAN BRISBANE, PERTH, SYDNEY 6 ATP Cup H 24 Teams 6 JAN DOHA 8 Qatar ExxonMobil Open H 28 2 13 JAN ADELAIDE 1, 8 Adelaide International H 28 13 JAN AUCKLAND 8 ASB Classic H 28 3 20 JAN MELBOURNE Australian Open* H 128 4 5 3 FEB CORDOBA Cordoba Open CL 28 3 FEB MONTPELLIER Open Sud de France IH 28 3 FEB PUNE Tata Open Maharashtra H 28 6 10 FEB ROTTERDAM ABN AMRO World Tennis Tournament IH 32 CALENDAR 2020 10 FEB BUENOS AIRES Argentina Open CL 28 10 FEB NEW YORK New York Open IH 28 7 17 FEB RIO DE JANEIRO Rio Open presented by Claro CL 32 17 FEB DELRAY BEACH Delray Beach Open by VITACOST.com H 32 17 FEB MARSEILLE Open 13 Provence IH 28 8 24 FEB ACAPULCO 8 Abierto Mexicano Telcel presentado por HSBC H 32 24 FEB DUBAI 8 Dubai Duty Free Tennis Championships H 32 24 FEB SANTIAGO Chile Open CL 28 9 6 MAR Davis Cup Qualifiers* 10 12 MAR INDIAN WELLS 5 BNP Paribas Open H 96 11 12 25 MAR MIAMI 4 Miami Open presented by Itau H 96 13 14 6 APR HOUSTON Fayez Sarofim & Co. U.S. Men’s Clay Court Championship CL 28 6 APR MARRAKECH Grand Prix Hassan II CL 32 15 12 APR MONTE CARLO 1 Rolex Monte-Carlo Masters CL 56 16 20 APR BARCELONA Barcelona Open Banc Sabadell CL 48 20 APR BUDAPEST Hungarian Open CL 28 17 27 APR ESTORIL Millennium Estoril Open CL 28 27 APR MUNICH BMW Open by FWU CL 28 18 3 MAY MADRID 1 Mutua Madrid Open CL 56 19 10 MAY ROME 1 Internazionali BNL d’Italia CL 56 20 17 MAY GENEVA 1, 8 Banque Eric Sturdza Geneva Open CL 28 17 MAY LYON 1, 8 Open -

2020 Annual Report for Tennis Scotland

ANNUALTENNIS SCOTLAND ANNUALREPORT REPORT 2020 1 Chair’s Welcome Graham Watson | Chair, Tennis Scotland Thanks to the excellent work of my predecessor Scott Martin, and the continued endeavours and commitment of our CEO Blane Dodds, I have been able to join Tennis Scotland at an exciting time for the organisation and the sport. With a very positive platform from which to deliver continued growth now in place , I look to continue the ambition that is clearly present in the organisation for developing all aspects of the sport for everyone to benefit from. Board of Directors The last year proved to be a particularly and Jonny O’Mara who continue to progress in Substantial hurdles stood in our way as the challenging one but one that was aided by the Grand Slams. Maia Lumsden also made an country adapted to changing environments all involved within the tennis community with impression in competitions, winning the British and a new way of life. However our new events their positivity and solution orientated approach. Tour at Roehampton before competing in the proved popular and allowed participants to We were all delighted that the Tennis Scotland Battle of the Brits alongside Jamie and Andy return to competition. The vast turnout to these Honorary President Guidelines were adopted by the Scottish Murray, Cameron Norrie, Jonny O’Mara events highlighted that the appetite for playing Dennis D Carmichael OBE Government and sportscotland early on to allow and Aidan McHugh. is most certainly still intact. I know that the tennis as one of the first sports back to activity executive and the Board have ambitious plans in June 2020 following a period of lockdown. -

Nanjing 2014 Youth Olympic Games Table Tennis Media Guide

Nanjing 2014 Youth Olympic Games Table Tennis Media Guide Table Tennis Events: 17 - 23 Aug 2014 Wutaishan Sports Gymnasium “Fan Zhendong is a genius for me; he doesn’t have a secret but he’s simply a genius; If his opponent hits six balls on the table, he finds a way to put the seventh back on; if his opponent hits seven balls on the table, he will hit the eighth!” - Xiao Zhan Personal coach of Olympic & World Champion Zhang Jike Fan Zhendong (CHN) Currently No. 3 in the world in the senior world rankings, Fan was part of the Chinese team that became senior World Champions earlier this year in Tokyo, Japan. He was also the youngest ever ITTF World Tour winner when he won the 2013 Polish Open at just 16 years and 292 days old. Fan Zhendong and Liu Gaoyang won the Mixed Doubles title at 2012 World Junior Championships in Hyderabad; they will join forces again in Nanjing. CONTENTS ITTF Overview 4 History of Table Tennis 4 YOG Table Tennis Event Schedule 5 YOG Table Tennis Event Location 6 YOG Playing System* 7 Qualification Process* 10 Table Tennis Key Facts* 12 YOG Athlete Role Model Profiles 14 Seeding 16 Mixed Teams Composition 17 Player Profile - Male 18 Player Profile - Female 34 YOG RAINBOW 50 Basic Table Tennis Rules 51 ITTF Global Junior Programme 52 2010 YOG Medallists 54 Current World Junior Champions 55 2014 Global Junior Circuit Event Winners 56 Upcoming ITTF Major Events 58 Media Tools 59 ITTF Media Contacts 59 * 内附中文版本 17 - 23 August 2014, Nanjing, China | 3 ITTF OVERVIEW The International Table Tennis Federation (ITTF) is the international governing body of Table Tennis and has 220 affiliated member associations; it is the equal first out of any International Sports Federation.