Configuring IP Intervlan Routing on an External Cisco Router

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cisco Etherchannel Technology

White Paper Cisco EtherChannel Technology Introduction The increasing deployment of switched Ethernet to the desktop can be attributed to the proliferation of bandwidth-intensive intranet applications. Any-to-any communications of new intranet applications such as video to the desktop, interactive messaging, and collaborative white-boarding are increasing the need for scalable bandwidth within the core and at the edge of campus networks. At the same time, mission-critical applications call for resilient network designs. With the wide deployment of faster switched Ethernet links in the campus, users need to either aggregate their existing resources or upgrade the speed in their uplinks and core to scale performance across the network backbone. Cisco EtherChannel® technology builds Cisco EtherChannel technology provides upon standards-based 802.3 full-duplex incremental scalable bandwidth and the Fast Ethernet to provide network managers following benefits: with a reliable, high-speed solution for the • Standards-based—Cisco EtherChannel campus network backbone. EtherChannel technology builds upon IEEE technology provides bandwidth scalability 802.3-compliant Ethernet by grouping within the campus by providing up to 800 multiple, full-duplex point-to-point Mbps, 8 Gbps, or 80 Gbps of aggregate links together.EtherChannel technology bandwidth for a Fast EtherChannel, uses IEEE 802.3 mechanisms for Gigabit EtherChannel, or 10 Gigabit full-duplex autonegotiation and EtherChannel connection, respectively. autosensing, when applicable. Each of these connection speeds can vary in • Multiple platforms—Cisco amounts equal to the speed of the links used EtherChannel technology is flexible and (100 Mbps, 1 Gbps, or 10 Gbps). Even in can be used anywhere in the network the most bandwidth-demanding situations, that bottlenecks are likely to occur. -

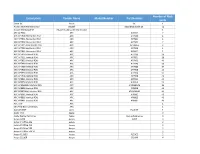

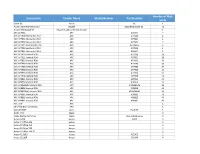

Smartzone 7.1 Device Catalog

Number of Rack Description Vendor Name Model Number Part Number Units 3com 8C 3com 8C 1 Alcatel 3600 Mainstreet 23 Alcatel 3600 Mainstreet 23_ 11 Alcatel Omnistack-24 Alcatel Sistemas de Informacion 1 APC ACF002 APC ACF002 2 APC AP7900 Horizontal PDU APC AP7900 1 APC AP7901 Horizontal PDU APC AP7901 1 APC AP7902 Horizontal PDU APC AP7902 2 APC AP7911A Horizontal PDU APC AP7911A 2 APC AP7920 Horizontal PDU APC AP7920 1 APC AP7921 Horizontal PDU APC AP8921 1 APC AP7930 Vertical PDU APC AP7930 36 APC AP7931 Vertical PDU APC AP7931 28 APC AP7932 Vertical PDU APC AP7932 40 APC AP7940 Vertical PDU APC AP7940 36 APC AP7960 Vertical PDU APC AP7960 37 APC AP7968 Vertical PDU APC AP7968 40 APC AP7990 Vertical PDU APC AP7990 37 APC AP7998 Vertical PDU APC AP7998 40 APC AP8941 Vertical PDU APC AP8941 42 APC AP8958 Vertical PDU APC AP8958 23 APC AP8958NA3 Vertical PDU APC AP8958NA3 23 APC AP8959 Vertical PDU APC AP8959 40 APC AP8959NA3 Vertical PDU APC AP8959NA3 40 APC AP8961 Vertical PDU APC AP8961 40 APC AP8965 Vertical PDU APC AP8965 40 APC AP8981 Vertical PDU APC AP8981 41 APC PDU APC 1 APC PDU Environmentals APC 1 Apex El 40DT Apex El_40DT 1 Apple iPad Apple 0 Apple Xserve Raid array Apple Xserve Raid array 3 Avaya G350 Avaya G350 3 Avaya IP Office 406 Avaya 2 Avaya IP Office 412 Avaya 2 Avaya IP Office 500 Avaya 2 Avaya IP Office 500 V2 Avaya 2 Avaya P133G2 Avaya P133G2 2 Avaya S3210R Avaya S3210R 4 Number of Rack Description Vendor Name Model Number Part Number Units Avaya S8500C Avaya S8500C 1 Avaya S8720 Avaya S8720 2 Nortel 8610 Avaya (Rapid -

Carrier Ethernet Ciena’S Essential Series: Be in the Know

Essentials Carrier Ethernet Ciena’s Essential Series: Be in the know. by John Hawkins with Earl Follis Carrier Ethernet Networks Published by Ciena 7035 Ridge Rd. Hanover, MD 21076 Copyright © 2016 by Ciena Corporation. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Ciena Corporation. For information regarding permission, write to: Ciena Experts Books 7035 Ridge Rd Hanover, MD 21076. Trademarks: Ciena, all Ciena logos, and other associated marks and logos are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Ciena Corporation both within and outside the United States of America, and may not be used without written permission. LIMITATION OF LIABILITY/DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTY: THE PUBLISHER AND THE AUTHOR MAKE NO REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES WITH RESPECT TO THE ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS OF THE CONTENTS OF THIS WORK AND SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION WARRANTIES OF FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. NO WARRANTY MAY BE CREATED OR EXTENDED BY SALES OR PROMOTIONAL MATERIALS. THE ADVICE AND STRATEGIES CONTAINED HEREIN MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR EVERY SITUATION. THIS WORK IS SOLD WITH THE UNDERSTANDING THAT THE PUBLISHER IS NOT ENGAGED IN RENDERING LEGAL, ACCOUNTING, OR OTHER PROFESSIONAL SERVICES. IF PROFESSIONAL ASSISTANCE IS REQUIRED, THE SERVICES OF A COMPETENT PROFESSIONAL PERSON SHOULD BE SOUGHT. NEITHER THE PUBLISHER NOR THE AUTHOR SHALL BE LIABLE FOR DAMAGES ARISING HEREFROM. THE FACT THAT AN ORGANIZATION OR WEBSITE IS REFERRED TO IN THIS WORK AS A CITATION AND/OR A POTENTIAL SOURCE OF FURTHER INFORMATION DOES NOT MEAN THAT THE AUTHOR OR THE PUBLISHER ENDORSES THE INFORMATION THE ORGANIZATION OR WEBSITE MAY PROVIDE OR RECOMMENDATIONS IT MAY MAKE. -

Top-Down Network Design Third Edition

Top-Down Network Design Third Edition Priscilla Oppenheimer Priscilla Oppenheimer Cisco Press 800 East 96th Street Indianapolis, IN 46240 ii Top-Down Network Design Top-Down Network Design, Third Edition Priscilla Oppenheimer Copyright© 2011 Cisco Systems, Inc. Published by: Cisco Press 800 East 96th Street Indianapolis, IN 46240 USA All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review. Printed in the United States of America First Printing August 2010 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file. ISBN-13: 978-1-58720-283-4 ISBN-10: 1-58720-283-2 Warning and Disclaimer This book is designed to provide information about top-down network design. Every effort has been made to make this book as complete and as accurate as possible, but no warranty or fitness is implied. The information is provided on an “as is” basis. The author, Cisco Press, and Cisco Systems, Inc. shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damages arising from the information contained in this book or from the use of the discs or programs that may accompany it. The opinions expressed in this book belong to the author and are not necessarily those of Cisco Systems, Inc. Trademark Acknowledgments All terms mentioned in this book that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. -

Network Switch from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia for Other Uses, See Switch (Disambiguation)

Network switch From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For other uses, see Switch (disambiguation). Avaya ERS 2550T-PWR 50-port network switch A network switch (sometimes known as a switching hub) is a computer networking device that is used to connect devices together on acomputer network by performing a form of packet switching. A switch is considered more advanced than a hub because a switch will only send a message to the device that needs or requests it, rather than broadcasting the same message out of each of its ports.[1] A switch is a multi-port network bridge that processes and forwards data at the data link layer (layer 2) of the OSI model. Some switches have additional features, including the ability to route packets. These switches are commonly known as layer-3 or multilayer switches.Switches exist for various types of networks including Fibre Channel, Asynchronous Transfer Mode, InfiniBand, Ethernet and others. The first Ethernet switch was introduced by Kalpana in 1990.[2] Contents [hide] 1 Overview o 1.1 Network design o 1.2 Applications o 1.3 Microsegmentation 2 Role of switches in a network 3 Layer-specific functionality o 3.1 Layer 1 (Hubs versus higher-layer switches) o 3.2 Layer 2 o 3.3 Layer 3 o 3.4 Layer 4 o 3.5 Layer 7 4 Types of switches o 4.1 Form factor o 4.2 Configuration options . 4.2.1 Typical switch management features 5 Traffic monitoring on a switched network 6 See also 7 References 8 External links Overview[edit] Cisco small business SG300-28 28-port Gigabit Ethernet rackmount switch and its internals A switch is a device used on a computer network to physically connect devices together. -

0470869828.Bindex.Pdf

INDEX 951 INDEX 952 INDEX A 1000-CX, 448, 452 AAL, 793 1000Base-LX, 448, 451 AAL1, 794 1000Base-SX, 448, 451 AAL3/4, 794 100Base-FX, 439, 440, 444 ABM, 808, 812 100Base-T4, 439, 442, 444 ABR, 799 100Base-TX, 439, 440, 441, Abramson, Norman, 389 442, 444 Accelerated MPLS full-duplex, 442 switching, 832 100VG-AnyLAN, 389, 410, Access: 436, 437, 442, 446, 448 lists, 728 10Base-2, 413, 416, 417, 752 methods, 392 10Base-5, 413, 414, 417 network, 150, 151, 164 10Base-F, 413, 438 point, 328, 468, 474 10Base-FB, 413, 421, 428 router, 755 10Base-FL, 413, 421, 428 token, 92 10Base-T, 117, 413, 420, 421, 427, 428, ACK, 195, 684 437, 438, 441, 752 frame, 476 full-duplex, 441 ACR, 261, 268 ports, 491 Active concentrator, 461 10G Ethernet, 388, 397, 436, 540, Ad-hoc networks, 474 753, 812 Adapter, 30 10GBase-LX4, 540 Adaptive Load Balancing, 557 10GBase-R, 540 Adaptive routing, 692 10GBase-W, 540 ADC, 292, 293 10GBase-X, 540 Add-Drop Multiplexer, 355 16-QAM, 289 Add/drop ports, 351, 354 Address: 2G mobile cellular anycast, 41, 45 networks, 471 broadcast, 45 3Com, 400, 436 hardware, 46 3G mobile cellular MAC, 46 networks, 468, 471, 893 multicast, 45, 588 4B/5B code 294, 300, 464 numeric, 45 5-4-3 rule, 416 symbolic, 45 802.11a, 468, 473 table, 513 802.11b, 473 unicast, 45, 588 802.16 standard, 861 Address Resolution 802.1p/Q, 568 Protocol (ARP), 48, 597 802.2, 409 Address space, 46 802.3/LLC frame, 408 flat, 46 802.3z, 451 hierarchical, 41, 46 INDEX 953 Addressing, 45 ARP, 597, 817 Administrative unit, 353 cache, 601 ADSL, 168, 170, 860, 864, 886 server, -

CCDA Exam Certification Guide

CH01.book Page i Friday, January 7, 2000 5:35 PM CCDA Exam Certification Guide A. Anthony Bruno, CCIE #2738 Jacqueline Kim, CCDA Cisco Press 201 W 103rd Street Indianapolis, IN 46290 CH01.book Page ii Friday, January 7, 2000 5:35 PM ii CCDA Exam Certification Guide A. Anthony Bruno Jacqueline Kim Copyright© 2000 Cisco Press Cisco Press logo is a trademark of Cisco Systems, Inc. Published by: Cisco Press 201 West 103rd Street Indianapolis, IN 46290 USA All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written per- mission from the publisher, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review. Printed in the United States of America 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Number: 99-64086 ISBN: 0-7357-0074-5 Warning and Disclaimer This book is designed to provide information about the CCDA examination. Every effort has been made to make this book as complete and as accurate as possible, but no warranty or fitness is implied. The information is provided on an “as is” basis. The author, Cisco Press, and Cisco Systems, Inc., shall have neither lia- bility nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damages arising from the information con- tained in this book or from the use of the discs or programs that may accompany it. The opinions expressed in this book belong to the authors and are not necessarily those of Cisco Systems, Inc. -

Cisco Catalyst 2950 Series Switches with Cisco Standard Image and Enhanced Image Software

Q&A Cisco Catalyst 2950 Series Switches with Cisco Standard Image and Enhanced Image Software PRODUCT OVERVIEW Q. What devices comprise the Cisco® Catalyst® 2950 Series Switches? A. The Cisco Catalyst 2950G 12 EI, Catalyst 2950G 24 EI, Catalyst 2950G 24 EI DC, and Catalyst 2950G 48 EI Switches are stackable switches that offer wire-speed connectivity to the desktop and gigabit uplink connectivity using several optional gigabit interface converter (GBIC) uplinks. These products, as well as the Cisco Catalyst 2950T 24 and Catalyst 2950C 24 Switches, deliver intelligent services such as availability, network security, and quality of service (QoS) to the network edge—using the simple Cisco Network Assistant software with a GUI-based interface. These switches come with Cisco Enhanced Image software installed to provide intelligent services. The Cisco Catalyst 2950C 24 and Catalyst 2950T 24 Switches belong to the Cisco Catalyst 2950 series of high-performance, standalone, 10/100 autosensing Fast Ethernet and Gigabit Ethernet switches. Both products bring intelligent services to the network edge to accommodate the needs of growing workgroups and server connectivity. The Cisco Catalyst 2950C 24 provides 24 10/100 ports plus 2 fixed 100BASE-FX ports. The Cisco Catalyst 2950T 24 offers medium-sized enterprises an easy migration path to Gigabit Ethernet by using existing copper cabling infrastructure with 24 10/100 ports plus 2 fixed 10/100/1000BASE-T uplinks. Embedded in the Cisco Catalyst 2950 Series is Cisco Device Manager software, which allows users to configure and troubleshoot a Cisco Catalyst fixed-configuration switch using a standard Web browser. The Cisco Catalyst 2950SX 48 SI and Catalyst 2950T 48 SI Switches are fixed-configuration, managed 10/100 switches that provide basic workgroup connectivity for small to medium-sized companies. -

Ethernet - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Página 1 De 12

Ethernet - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Página 1 de 12 Ethernet From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The five-layer TCP/IP model Ethernet is a family of frame-based computer 5. Application layer networking technologies for local area networks (LANs). The name comes from the physical concept of DHCP · DNS · FTP · Gopher · HTTP · the ether. It defines a number of wiring and signaling IMAP4 · IRC · NNTP · XMPP · POP3 · standards for the physical layer, through means of SIP · SMTP · SNMP · SSH · TELNET · network access at the Media Access Control RPC · RTCP · RTSP · TLS · SDP · (MAC)/Data Link Layer, and a common addressing SOAP · GTP · STUN · NTP · (more) format. 4. Transport layer Ethernet is standardized as IEEE 802.3. The TCP · UDP · DCCP · SCTP · RTP · combination of the twisted pair versions of Ethernet for RSVP · IGMP · (more) connecting end systems to the network, along with the 3. Network/Internet layer fiber optic versions for site backbones, is the most IP (IPv4 · IPv6) · OSPF · IS-IS · BGP · widespread wired LAN technology. It has been in use IPsec · ARP · RARP · RIP · ICMP · from the 1990s to the present, largely replacing ICMPv6 · (more) competing LAN standards such as token ring, FDDI, 2. Data link layer and ARCNET. In recent years, Wi-Fi, the wireless LAN 802.11 · 802.16 · Wi-Fi · WiMAX · standardized by IEEE 802.11, is prevalent in home and ATM · DTM · Token ring · Ethernet · small office networks and augmenting Ethernet in FDDI · Frame Relay · GPRS · EVDO · larger installations. HSPA · HDLC · PPP · PPTP · L2TP · ISDN -

Cisco Prime Network Supported Technologies and Topologies, 4-3.2

Cisco Prime Network 4.3.2 Supported Technologies and Topologies July, 2017 Americas Headquarters Cisco Systems, Inc. 170 West Tasman Drive San Jose, CA 95134-1706 USA http://www.cisco.com Tel: 408 526-4000 800 553-NETS (6387) Fax: 408 527-0883 [Type text] Abstract Abstract THE SPECIFICATIONS AND INFORMATION REGARDING THE PRODUCTS IN THIS MANUAL ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE. ALL STATEMENTS, INFORMATION, AND RECOMMENDATIONS IN THIS MANUAL ARE BELIEVED TO BE ACCURATE BUT ARE PRESENTED WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED. USERS MUST TAKE FULL RESPONSIBILITY FOR THEIR APPLICATION OF ANY PRODUCTS. THE SOFTWARE LICENSE AND LIMITED WARRANTY FOR THE ACCOMPANYING PRODUCT ARE SET FORTH IN THE INFORMATION PACKET THAT SHIPPED WITH THE PRODUCT AND ARE INCORPORATED HEREIN BY THIS REFERENCE. IF YOU ARE UNABLE TO LOCATE THE SOFTWARE LICENSE OR LIMITED WARRANTY, CONTACT YOUR CISCO REPRESENTATIVE FOR A COPY. The Cisco implementation of TCP header compression is an adaptation of a program developed by the University of California, Berkeley (UCB) as part of UCB’s public domain version of the UNIX operating system. All rights reserved. Copyright © 1981, Regents of the University of California. NOTWITHSTANDING ANY OTHER WARRANTY HEREIN, ALL DOCUMENT FILES AND SOFTWARE OF THESE SUPPLIERS ARE PROVIDED “AS IS” WITH ALL FAULTS. CISCO AND THE ABOVE-NAMED SUPPLIERS DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, THOSE OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NON INFRINGEMENT OR ARISING FROM A COURSE OF DEALING, USAGE, OR TRADE PRACTICE. IN NO EVENT SHALL CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY INDIRECT, SPECIAL, CONSEQUENTIAL, OR INCIDENTAL DAMAGES, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, LOST PROFITS OR LOSS OR DAMAGE TO DATA ARISING OUT OF THE USE OR INABILITY TO USE THIS MANUAL, EVEN IF CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS HAVE BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES. -

Smartzone 7.1 Device Catalog

Number of Rack Description Vendor Name Model Number Part Number Units 3com 8C 3com 8C 1 Alcatel 3600 Mainstreet 23 Alcatel 3600 Mainstreet 23_ 11 Alcatel Omnistack-24 Alcatel Sistemas de Informacion 1 APC ACF002 APC ACF002 2 APC AP7900 Horizontal PDU APC AP7900 1 APC AP7901 Horizontal PDU APC AP7901 1 APC AP7902 Horizontal PDU APC AP7902 2 APC AP7911A Horizontal PDU APC AP7911A 2 APC AP7920 Horizontal PDU APC AP7920 1 APC AP7921 Horizontal PDU APC AP8921 1 APC AP7930 Vertical PDU APC AP7930 36 APC AP7931 Vertical PDU APC AP7931 28 APC AP7932 Vertical PDU APC AP7932 40 APC AP7940 Vertical PDU APC AP7940 36 APC AP7960 Vertical PDU APC AP7960 37 APC AP7968 Vertical PDU APC AP7968 40 APC AP7990 Vertical PDU APC AP7990 37 APC AP7998 Vertical PDU APC AP7998 40 APC AP8941 Vertical PDU APC AP8941 42 APC AP8958 Vertical PDU APC AP8958 23 APC AP8958NA3 Vertical PDU APC AP8958NA3 23 APC AP8959 Vertical PDU APC AP8959 40 APC AP8959NA3 Vertical PDU APC AP8959NA3 40 APC AP8961 Vertical PDU APC AP8961 40 APC AP8965 Vertical PDU APC AP8965 40 APC AP8981 Vertical PDU APC AP8981 41 APC PDU APC 1 APC PDU Environmentals APC 1 Apex El 40DT Apex El_40DT 1 Apple iPad Apple 0 Apple Xserve Raid array Apple Xserve Raid array 3 Avaya G350 Avaya G350 3 Avaya IP Office 406 Avaya 2 Avaya IP Office 412 Avaya 2 Avaya IP Office 500 Avaya 2 Avaya IP Office 500 V2 Avaya 2 Avaya P133G2 Avaya P133G2 2 Avaya S3210R Avaya S3210R 4 Number of Rack Description Vendor Name Model Number Part Number Units Avaya S8500C Avaya S8500C 1 Avaya S8720 Avaya S8720 2 Nortel 8610 Avaya (Rapid -

Troubleshooting LAN Switching Environments

CHAPTER23 Troubleshooting LAN Switching Environments The sections in this chapter describe common LAN switch features and offer solutions to some of the most common LAN switching problems. The following items will be covered: • LAN Switching Introduction • General Switch Troubleshooting Suggestions • Troubleshooting Port Connectivity Problems • Troubleshooting Ethernet 10/100-Mb Half-/Full-Duplex Autonegotiation • ISL Trunking on Catalyst 5000 and 6000 Family Switches • Example of Configuring and Troubleshooting Ethernet 10/100-Mb Autonegotiation • Configuring EtherChannel Switch-to-Switch on Catalyst 4000/5000/6000 Switches • Using PortFast and Other Commands to Fix End-Station Startup Connectivity Problems • Configuring and Troubleshooting IP Multilayer Switching • Troubleshooting Spanning Tree Protocol and Related Design Considerations LAN Switching Introduction If you are new to LAN switching, then the following sections will take you through some of the main concepts related to switches. One of the prerequisites to troubleshooting any device is to know the rules under which it operates. Switches have become much more complex over the last few years as they have gained popularity and sophistication. The next few paragraphs describe some of the key concepts to know about switches. Hubs and Switches Because of the great demand placed on local-area networks, we have seen a shift from a shared-bandwidth network, using hubs and coaxial cable, to a dedicated bandwidth network, using switches. A hub allows multiple devices to be connected to the same network segment. The devices on that segment share the bandwidth with each other. If it is a 10-Mb hub and six devices are connected to six different ports on the hub, all six devices would share the 10 Mb of bandwidth with each other.