Technical Report Number 41 Western Gulf of Alaska Petroleum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries Atlas of Whether used as a scholarly introduction into Eastern Christian monasticism or researcher’s directory or a travel guide, Alexei Krindatch brings together a fascinating collection of articles, facts, and statistics to comprehensively describe Orthodox Christian Monasteries in the United States. The careful examina- Atlas of American Orthodox tion of the key features of Orthodox monasteries provides solid academic frame for this book. With enticing verbal and photographic renderings, twenty-three Orthodox monastic communities scattered throughout the United States are brought to life for the reader. This is an essential book for anyone seeking to sample, explore or just better understand Orthodox Christian monastic life. Christian Monasteries Scott Thumma, Ph.D. Director Hartford Institute for Religion Research A truly delightful insight into Orthodox monasticism in the United States. The chapters on the history and tradition of Orthodox monasticism are carefully written to provide the reader with a solid theological understanding. They are then followed by a very human and personal description of the individual US Orthodox monasteries. A good resource for scholars, but also an excellent ‘tour guide’ for those seeking a more personal and intimate experience of monasticism. Thomas Gaunt, S.J., Ph.D. Executive Director Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) This is a fascinating and comprehensive guide to a small but important sector of American religious life. Whether you want to know about the history and theology of Orthodox monasticism or you just want to know what to expect if you visit, the stories, maps, and directories here are invaluable. -

Patterns in the Adoption of Russian National Traditions by Alaskan

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 360 European Multilingualism: Shaping Sustainable Educational and Social Environment (EMSSESE 2019) Patterns in the Adoption of Russian Linguistic and National Traditions by Alaskan Natives Ivan Savelev Department of international law and comparative jurisprudence Northern (Arctic) Federal University Arkhangelsk, Russia [email protected] Research supported by Russian Scientific Fund (project № 17–18–01567) Abstract: During the past two and a half centuries adopt Russian traditions and integrate them into their own the traditions and culture of the native people of Alaska unique cultures. have been affected first by the Russian and then by the Anglo-American culture. The traces of the Russian II. METHOD AND THEORETICAL BACKGROUND influence can be observed even 150 years after the Critical analysis of regulatory, narrative, and other cession of this territory to the US, as verified by the historical sources was implemented to meet the study expeditions of Russian America Heritage Project objective. The Russian cultural borrowings were documenting sustained the Russian influence, the identified during the Russian America Heritage Project religious one in the first place. At the initial stage of with the help of semi-structured interviews with exploration of Russian America, influence was representatives of the native groups of Alaska, based on a predominantly exercised through taking amanats pre-generated questionnaire followed by the reviews of (hostages) resulting in close contacts between the the data acquired. Russian fur hunters and the representatives of native population. In contrast to Siberia, where this practice Between the 1860s and the present day, the European originated from, Alaskan amanats were treated quite civilization in its Anglo-American form began affecting kindly and passed the Russian customs and traditions to regional populations. -

An Ethnography of Old Harbor and Ouzinkie, Alaska

BLACK DUCKS AND SALMON BELLIES An Ethnography of Old Harbor and Ouzinkie, Alaska by Craig Mishler Technical Memorandum No. 7 A Report Produced for the U.S. Minerals Management Service Cooperative Agreement 14-35-0001-30788 March 2001 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Subsistence 333 Raspberry Road Anchorage, Alaska 99518 This report has been reviewed by the Minerals Management Service and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. ADA PUBLICATIONS STATEMENT The Alaska Department of Fish and Game operates all of its public programs and activities free from discrimination on the basis of sex, color, race, religion, national origin, age, marital status, pregnancy, parenthood, or disability. For information on alternative formats available for this and other department publications, please contact the department ADA Coordinator at (voice) 907- 465-4120, (TDD) 1-800-478-3548 or (fax) 907-586-6595. Any person who believes she or he has been discriminated against should write to: Alaska Department of Fish and Game PO Box 25526 Juneau, AK 99802-5526 or O.E.O. U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ...............................................................................................................................iii List of Figures ...............................................................................................................................iii -

Kodiak Island Is a Part of an Archipelago of Islands Including Afognak, Shuyak, and 20 Smaller Islands

Southcentral Region Southcentral Alaska Alaska Department of Fish and Game Recreational Fishing Series Division of Sport Fish Kodiak About Kodiak Kodiak Island is a part of an archipelago of islands including Afognak, Shuyak, and 20 smaller islands. Kodiak Island is the second-largest in the United States; only the big island of Hawaii is larger. The Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge covers two-thirds of Kodiak Island. The State of Alaska, various Alaska Native corporations, and private individuals own the remainder. The city of Kodiak is 250 air miles southwest of Anchorage. Two airlines, Alaska Airlines (1-800-252-7522) and ERA Airlines (1-800-866-8394), have daily flights from Anchorage. The Alaska Marine Highway system offers a passenger and vehicle ferry from Homer and Seward to Kodiak four times a week during the fishing season (1-800-642- 0066). About 11,000 people live along the Kodiak Island’s streams and lakes offer easily accessible and remote fishing Kodiak road system, and 14,000 opportunities for salmon, steelhead, Dolly Varden (above) and more. (ADF&G) visitors arrive every year. Available services include approximately 70 Regulations on the Road System differ slightly from charter operators, 33 remote lodges, six air taxi services, the Remote Area, so check the regulations book carefully. 12 state and federal public-use cabins, 10 private remote There are 75 miles of paved and hard-packed gravel roads cabins for rent, five hotels and motels, 30 bed-and- that cross 10 significant streams and provide access to 18 breakfasts, three sporting goods stores, and other amenities stocked lakes. -

Exploring Kodiak Alutiiq Literature Through Core Values

LIITUKUT SUGPIAT’STUN (WE ARE LEARNING HOW TO BE REAL PEOPLE): EXPLORING KODIAK ALUTIIQ LITERATURE THROUGH CORE VALUES A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Alisha Susana Drabek, BA., M.F.A. Fairbanks, Alaska December 2012 UMI Number: 3537832 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3537832 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 LIITUKUT SUGPIAT’ STUN (WE ARE LEARNING HOW TO BE REAL PEOPLE): EXPLORING KODIAK ALUTIIQ LITERATURE THROUGH CORE VALUES By Alisha Susana Drabek Abstract The decline of Kodiak Alutiiq oral tradition practices and limited awareness or understanding of archived stories has kept them from being integrated into school curriculum. This study catalogs an anthology of archived Alutiiq literature documented since 1804, and provides an historical and values-based analysis of Alutiiq literature, focused on the educational significance of stories as tools for individual and community wellbeing. The study offers an exploration of values, worldview and knowledge embedded in Alutiiq stories. -

Surname Distributions, Origins, and Their Association with Y-Chromosome Markers in the Aleutian Archipelago

Surname Distributions, Origins, and their Association with Y-chromosome Markers in the Aleutian Archipelago By Copyright 2010 Orion Mark Graf Submitted to the Graduate Program in Anthropology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts Dr. Michael H. Crawford (Chairperson) Dr. James H. Mielke Committee members Dr. Bartholomew C. Dean Date defended: July 12th, 2010 The Thesis Committee for Orion Mark Graf certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Surname Distributions, Origins, and their Association with Y-chromosome Markers in the Aleutian Archipelago Committee: Dr. Michael H. Crawford (Chairperson) Dr. James H. Mielke Dr. Bartholomew C. Dean Date accepted: July 12th, 2010 ii Abstract This study is an examination of the geographic distribution and ethnic origins of surnames as well as their association with Y-chromosome haplogroups found in Native communities from the Aleutian Archipelago. The project’s underlying hypothesis is that surnames and Y-chromosome haplogroups are correlated in the Aleutian Islands because both are paternally inherited markers. Using 732 surnames, Lasker’s Coefficient of relationship through isonymy (Rib) was used to identify correlations between each community based on of surnames. A subsample of 143 surnames previously characterized using Y-chromosome markers were used to directly contrast the two markers using frequency distributions and tests. Overall, it was observed that the distribution of surnames in the Aleutian Archipelago is culturally driven, rather than one of paternal inheritance. Surnames follow a gradient from east to west, with high frequencies of Russian surnames found in western Aleut communities and high levels of non- Russian surnames found in eastern Aleut communities. -

Michael Z. Vinokouroff: a Profile and Inventory of His Papers And

MICHAEL Z. VINOKOUROFF: A PROFILE AND INVENTORY OF HIS PAPERS (Ms 81) AND PHOTOGRAPHS (PCA 243) in the Alaska Historical Library Louise Martin, Ph.D. Project coordinator and editor Alaska Department of Education Division ofState Libraries P.O. Box G Juneau Alaska 99811 1986 Martin, Louise. Michael Z. Vinokouroff: a profile and inventory of his papers (MS 81) and photographs (PCA 243) in the Alaska Historical Library / Louise Martin, Ph.D., project coordinator and editor. -- Juneau, Alaska (P.O. Box G. Juneau 99811): Alaska Department of Education, Division of State Libraries, 1986. 137, 26 p. : ill.; 28 cm. Includes index and references to photographs, church and Siberian material available on microfiche from the publisher. Partial contents: M.Z. Vinokouroff: profile of a Russian emigre scholar and bibliophile/ Richard A. Pierce -- It must be done / M.Z.., Vinokouroff; trans- lation by Richard A. Pierce. 1. Orthodox Eastern Church, Russian. 2. Siberia (R.S.F.S.R.) 3. Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church of America--Diocese of Alaska--Archives-- Catalogs. 4. Vinokour6ff, Michael Z., 1894-1983-- Library--Catalogs. 5. Soviet Union--Emigrationand immigration. 6. Authors, Russian--20th Century. 7. Alaska Historical Library-- Catalogs. I. Alaska. Division of State Libraries. II. Pierce, Richard A. M.Z. Vinokouroff: profile of a Russian emigre scholar and bibliophile. III. Vinokouroff, Michael Z., 1894- 1983. It must be done. IV. Title. DK246 .M37 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................. 1 “M.Z. Vinokouroff: Profile of a Russian Émigré Scholar and Bibliophile,” by Richard A. Pierce................... 5 Appendix: “IT MUST BE DONE!” by M.Z. Vinokouroff; translation by Richard A. -

Kodiak About Kodiak Kodiak Island Is a Part of an Archipelago of Islands That Includes Afognak Island, Shuyak Island, and 20 Smaller Islands

Southcentral Region Alaska Department of Fish and Game Southcentral Alaska Division of Sport Fish Recreational Fishing Series Kodiak About Kodiak Kodiak Island is a part of an archipelago of islands that includes Afognak Island, Shuyak Island, and 20 smaller islands. The island is the second-largest in the United States, with the big island of Hawaii the only larger island. The Ko- diak National Wildlife Refuge covers 2/3 of Kodiak Island. The State of Alaska, various Alaska Native corporations, and private individuals own the remainder. The City of Kodiak is 250 air miles southwest of Anchor- age. Two airlines, Alaska Airlines (1-800-252-7522) and ERA Airlines (1-800-866-8394), have daily fl ights from Anchorage (depending on weather). The Alaska Marine Highway system offers a passenger and vehicle ferry from Homer and Seward to Kodiak four times a week during the A Kodiak Island king salmon. fi shing season (1-800-642-0066). About 11,000 people live along the Kodiak Road System, also includes all salt waters bordering the Road System and 14,000 visitors arrive every year. Available services within one mile of Spruce and Kodiak islands. include 70 charter operators, 33 remote lodges, 6 air taxis, Regulations on the Road System differ slightly from 12 state and federal public use cabins, 10 private remote the Remote Area, so check the Kodiak regulation book cabins for rent, 5 hotels and motels, 30 bed and breakfasts, carefully. 4 sporting good stores, as well as all the other amenities There are 70 miles of paved and hard-packed gravel usually found in a community this size. -

Environmental Ofthe Alaskan Continental Sheif

-------~.-.- - - \ Environmental Assessment ofthe Alaskan Continental SheIf Interim Synthesis Report: Kodiak February 1978 ~"O"'TMOS""'~-9/(, ~ .. <Y~ I •• \ us. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE ~ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration i-,)z '" c.O' ".6' Environmental Research Laboratories 0<",0.. ...~'" -9r"'flVT Of CO OUTER CONTINENTAL SHELF ENVIRONtv1ENTAL ASSESSMENT PROGRAM INTER 1M SYNTHES IS REPORT: I4JD IAK Prepared Under Contract By Science Applications, Inc. March 1978 ('I''''OATMO~<,?/C' -s' ~ 1 g • \ ~ ' National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration ':d.1-.~ " "e-", &~ Environmental Research Laboratories 0<"",.</ ""~,,,'Ii' 1/~"'ENTOftO Boulder, Colorado 80303 ;j NOTICE The Environmental Research Laboratories do not approve, recommend, or endorse any proprietary product or proprietary material mentioned in this publication. No reference shall be made to the Environmental Research Laboratories or to this publication furnished by the Environmental Research Laboratories in any advertising or sales promotion which would indicate or imply that the Environmental Research Laboratories approve, recommend, or endorse any proprietary product or proprietary material mentioned herein, or which has as its purpose an intent to cause directly or indirectly the advertised product to be used or purchased because of this Environmental Research Laboratories publication. i i --_ .. _---- - ---~--------_._- --- CONTENTS Chapter Page I.' INTRODUCTION . 1 OBJECTIVES AND HISTORY OF THE SYNTHESIS REPORT 1 CONTENTS OF THE REPORT . 2 LIMITATIONS . 3 PREVIOUS PUBLICATIONS . 3 I I.' REGIONS OF POSSIBLE IMPINGEMENT 5 INTRODUCTION . 5 REGION I: CHIRIKOF AND TRINITY ISLANDS. 6 REGION ·II:ALITAK BAY TO DANGEROUS CAPE . '9 REGION III: DANGEROUS CAPE TO SHUYAK ISLAND, INCLUDING OFFSHORE BANKS . .. 12 III. STATE OF KNOWLEDGE OVERVIEW . 18 BACKGROUND LEVELS OF PETROLEUM-RELATED CONTAMINANTS 18 GEOLOGIC HAZARDS . -

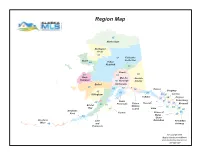

Alaska MLS Statewide Maps

Region Map 3E North Slope Northwest Arctic 3D 3F Fairbanks Nome North Star 4G Yukon Koyukuk 3C Denali 4H 3A 3B Wade Mat-Su Eastern Hampton 1D Borough Interior Bethel Anchorage 4C 1A 1B 1E Haines Skagway 4E 1B 2H Dillingham 2A 2F Juneau Yakutat Angoon 2F 2B Kenai 2F Petersburg 4D 2F Peninsula Prince Hoonah 2F Wrangell Bristol 4F 1C William 2E 2G Bay 2G 1C Sound Sitka 2D Aleutians Prince of 2C East Kodiak 2D 4A Wales - Outer Aleutians Lake Ketchikan Ketchikan West 4B and Gateway Peninsula (C)Copyright 2005 Map by Alaska Street Master www.alaskastreetmaster.com 907-243-0477 Eklutna Chugiak Peters Creek 100 Little Peters Creek Birchwood Loop Rd Fire Creek Old Glenn90 Hwy Carol Creek Meadow Creek Knik Arm Clunie Creek Eagle River Alaska Railroad 50 Eagle River Rd Mat-Su Fort Richardson Borough Eagle River Loop Rd Region 1D Fossil Creek Hiland Rd Eagle River Glenn Hwy Elmendorf AFB Point McKenzie Ship Creek 5 S Fork Eagle River Post Rd Glenn Hwy Ship Creek W 5TH Ave Debarr Rd Point Woronzof 15th Ave Northern Lights Blvd Muldoon Rd 45 Boniface Pkwy S Fork Chester Creek C St 40 Minnesota Dr 10 Tudor Rd Anchorage International Airport Rd Dowling Rd N Fork Campbell Creek Raspberry Rd 35 15 S Fork Campbell Creek Area# Area Description New Seward hwy 5 Downtown Anchorage Abbott Rd Abbott Loop Rd Jewel Lake Rd Sand Lake Rd 10 Spenard Dimond Blvd 20 15 West Tudor Rd - Dimond Blvd Lake Otis Pkwy Little Campbell Creek 20 Dimond South O'Malley Rd 30 25 Dearmoun Rd - Potter Marsh Southport Dr Birch Rd Hillside Dr Klatt Rd Elmore Rd 30 Abbott Rd - Dearmoun Rd Huffman Rd 35 East Tudor Rd - Abbott Rd 40 Seward Hwy to Boniface Pkwy DeArmoun Rd 45 Boniface Pkwy to Muldoon Rd Cook Inlet 50 Post Road - Glenn Hwy 90 Eagle River (Hiland Rd - S. -

Southwest Alaska Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy 2009-2014

Southwest Alaska Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy 2009-2014 Southwest Alaska Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy prepared for the United States Department of Commerce Economic Development Administration by Southwest Alaska Municipal Conference May 2010 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction .................................. 1 5.0 Population Trends & Future ..................................... 88 Characteristics .................... 36 Renewable Energy........................... 86 2.0 Southwest Alaska Municipal Population Trends ................................ 36 Hydroelectric ......................... 88 Conference ............................ 2 Gender ................................................. 42 Wind ....................................... 88 Mission ......................................... 2 Age ....................................................... 42 Biomas .................................... 89 Organization ................................. 2 Ethnicity ............................................... 42 Geothermal ............................. 89 Board of Directors & Educational Attainment ........................ 53 Solar ....................................... 89 CEDS Committee ........................ 3 Population Density .............................. 53 Hydrokinetic/Tidal.................. 90 SWAMC Staff .............................. 3 Population Projections ........................ 55 Alternative Energy ......................... 90 SWAMC Membership .................. 3 Fish Oil .................................. -

Legal Notice Kodiak Island Borough 710 Mill Bay Road Kodiak Ak 99615

LEGAL NOTICE KODIAK ISLAND BOROUGH 710 MILL BAY ROAD KODIAK AK 99615 NOTICE OF FORECLOSURE Take notice that on February 12, 2021 the Kodiak Island Borough has filed in the Superior Court, Third Judicial District, State of Alaska, a certified copy of the Foreclosure List for the Kodiak Island Borough for the year 2020 and prior years with a Petition for Judgment of Foreclosure. Pursuant to AS 29.45.330, the Foreclosure List is available for public inspec- tion at the Borough Clerk’s Office. Take further notice that in accordance with law, notice of foreclosure proceedings will be given by four weekly publi- cations of the following foreclosure list in the Kodiak Daily Mirror beginning February 12, 2021. Said foreclosure list shows the names of the persons appearing in the latest tax roll as the respective owner of the delinquent properties, the years for which the taxes are delinquent, the amount of the delinquent tax for the year, and penalty and interest thereon. Any person(s) owing or having a legal or equitable interest in, or lien upon any tract listed in said foreclosure, may no later than thirty (30) days after the last publication of this notice, file an answer with the Court in defense to the Petition for Judgment of Foreclosure. Such answer shall be in writing and specify the grounds or objection to the assessment of tax on the particular tract described in such answer and the Court in summary proceedings will hear and determine such objection and render such decision thereon as may be legal and just.