Outback Nevada: Public Domain and Environmental Challenge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HISTORY of the TOIYABE NATIONAL FOREST a Compilation

HISTORY OF THE TOIYABE NATIONAL FOREST A Compilation Posting the Toiyabe National Forest Boundary, 1924 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Chronology ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Bridgeport and Carson Ranger District Centennial .................................................................... 126 Forest Histories ........................................................................................................................... 127 Toiyabe National Reserve: March 1, 1907 to Present ............................................................ 127 Toquima National Forest: April 15, 1907 – July 2, 1908 ....................................................... 128 Monitor National Forest: April 15, 1907 – July 2, 1908 ........................................................ 128 Vegas National Forest: December 12, 1907 – July 2, 1908 .................................................... 128 Mount Charleston Forest Reserve: November 5, 1906 – July 2, 1908 ................................... 128 Moapa National Forest: July 2, 1908 – 1915 .......................................................................... 128 Nevada National Forest: February 10, 1909 – August 9, 1957 .............................................. 128 Ruby Mountain Forest Reserve: March 3, 1908 – June 19, 1916 .......................................... -

Download Download

10/23/2014 The Historical Roots of The Nature Conservancy in the Northwest Indiana/Chicagoland Region: From Science to Preservation Category: Vol. 3, 2009 The Historical Roots of The Nature Conservancy in the Northwest Indiana/Chicagoland Region: From Science to Preservation Written by Stephanie Smith and Steve Mark Hits: 10184 The South Shore Journal, Vol. 3, 2009, pp.1-10. Stephanie Smith - Indiana University Northwest Steve Mark - Chicago, Illinois Abstract The present article highlights the impact that scientists, educators, and activists of the Northwest Indiana/Chicagoland area had on the conservation of land. The habitat and ecosystems of the Indiana Dunes were deemed to be of scientific interest by Henry Cowles, who led an international group of ecologists to visit the area in 1913. This meeting resulted in the formation of the Ecological Society of America, an offshoot of which eventually became The Nature Conservancy. It was only when preservation efforts expanded their focus from scientists attempting to prove that habitats were worthy of preservation to include contributions by people from all walks of life, did conservation take off. Keywords: The Nature Conservancy, Ecologists Union, Volo Bog The Historical Roots of The Nature Conservancy in the Northwest Indiana/Chicagoland Region: From Science to Preservation …There is not a sufficient number of scientific people as voters to enthuse the politicians… …. (Garland, 1954). In the late 1890’s and early 1900’s, Henry Chandler Cowles, a botanist at the University of Chicago, published a number of scientific papers on ecological succession from research conducted in the sand dunes of northwestern Indiana (e.g., Cowles, 1899; Cowles, 1901). -

Thesis Polygamy on the Web: an Online Community for An

THESIS POLYGAMY ON THE WEB: AN ONLINE COMMUNITY FOR AN UNCONVENTIONAL PRACTICE Submitted by Kristen Sweet-McFarling Department of Anthropology In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2014 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Lynn Kwiatkowski Cindy Griffin Barbara Hawthorne Copyright by Kristen Sweet-McFarling 2014 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT POLYGAMY ON THE WEB: AN ONLINE COMMUNITY FOR AN UNCONVENTIONAL PRACTICE This thesis is a virtual ethnographic study of a polygamy website consisting of one chat room, several discussion boards, and polygamy related information and links. The findings of this research are based on the interactions and activities of women and men on the polygamy website. The research addressed the following questions: 1) what are individuals using the website for? 2) What are website members communicating about? 3) How are individuals using the website to search for polygamous relationships? 4) Are website members forming connections and meeting people offline through the use of the website? 5) Do members of the website perceive the Internet to be affecting the contemporary practice of polygamy in the U.S.? This research focused more on the desire to create a polygamous relationship rather than established polygamous marriages and kinship networks. This study found that since the naturalization of monogamous heterosexual marriage and the nuclear family has occurred in the U.S., due to a number of historical, social, cultural, political, and economic factors, the Internet can provide a means to denaturalize these concepts and provide a space for the expression and support of counter discourses of marriage, like polygamy. -

Final Environmental Impact Statement and Proposed Land-Use Plan

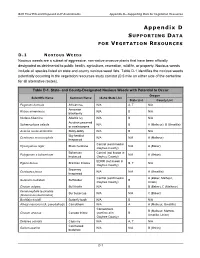

B2H Final EIS and Proposed LUP Amendments Appendix D—Supporting Data for Vegetation Resources Appendix D SUPPORTING DATA FOR VEGETATION RESOURCES D . 1 N O X I O U S W EEDS Noxious weeds are a subset of aggressive, non-native invasive plants that have been officially designated as detrimental to public health, agriculture, recreation, wildlife, or property. Noxious weeds include all species listed on state and county noxious weed lists. Table D-1 identifies the noxious weeds potentially occurring in the vegetation resources study corridor (0.5 mile on either side of the centerline for all alternative routes). Table D-1. State- and County-Designated Noxious Weeds with Potential to Occur Oregon Scientific Name Common Name Idaho State List State List County List Peganum harmala African rue N/A A, T N/A Armenian Rubus armeniacus N/A B N/A blackberry Hedera hibernica Atlantic Ivy N/A B N/A Austrian peaweed Sphaerophysa salsula N/A B A (Malheur), B (Umatilla) or swainsonpea Acaena novae-zelandiae Biddy-biddy N/A B N/A Big-headed Centaurea macrocephala N/A N/A A (Malheur) knapweed Control (confirmed in Hyoscyamus niger Black henbane N/A A (Baker) Owyhee County) Bohemian Control (not known in Polygonum x bohemicum N/A A (Union) knotweed Owyhee County) EDRR (not known in Egeria densa Brazilian Elodea B, T N/A Owyhee County) Brownray Centaurea jacea N/A N/A A (Umatilla) knapweed Control (confirmed in A (Baker, Malheur, Solanum rostratum Buffalobur B Owyhee County) Union) Cirsium vulgare Bull thistle N/A B B (Baker), C (Malheur) Ceratocephala testiculata Bur buttercup N/A N/A C (Baker) (Ranunculus testiculatus) Buddleja davidii Butterfly bush N/A B N/A Alhagi maurorum (A. -

Too Wild to Drill A

TOO WILD TO DRILL A The connection between people and nature runs deep, and the sights, sounds and smells of the great outdoors instantly remind us of how strong that connection is. Whether we’re laughing with our kids at the local fishing hole, hiking or hunting in the backcountry, or taking in the view at a scenic overlook, we all share a sense of wonder about what the natural world has to offer us. Americans around the nation are blessed with incredible wildlands out our back doors. The health of our public lands and wild places is directly tied to the health of our families, communities and economy. Unfortunately, our public lands and clean air and water are under attack. The Trump administration and some in Congress harbor deep ties to fossil fuel and mining interests, and today, resource extraction lobbyists see an unprecedented opportunity to open vast swaths of our public lands. Recent proposals to open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to drilling and shrink or eliminate protected lands around the country underscore how serious this threat is. Though some places are appropriate for responsible energy development, the current agenda in Washington, D.C. to aggressively prioritize oil, gas and coal production at the expense of all else threatens to push drilling and mining deeper into our wildest forests, deserts and grasslands. Places where families camp and hike today could soon be covered with mazes of pipelines, drill rigs and heavy machinery, or contaminated with leaks and spills. This report highlights 15 American places that are simply too important, too special, too valuable to be destroyed for short-lived commercial gains. -

Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks

B L M U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Decision Record - Memorandum Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks PREPARING OFFICE U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management 3900 E. Idaho St. Elko, NV 89801 Decision Record - Memorandum Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks Prepared by U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Elko, NV This page intentionally left blank Decision Record - Memorandum iii Table of Contents _1. Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks Decision Record Memorandum ....... 1 _1.1. Proposed Decision .......................................................................................................... 1 _1.2. Compliance ..................................................................................................................... 6 _1.3. Public Involvement ......................................................................................................... 7 _1.4. Rationale ......................................................................................................................... 7 _1.5. Authority ......................................................................................................................... 8 _1.6. Provisions for Protest, Appeal, and Petition for Stay ..................................................... 9 _1.7. Authorized Officer .......................................................................................................... 9 _1.8. Contact Person ............................................................................................................... -

PART II PERSONAL PAPERS and ORGANIZATIONAL RECORDS Allen, Paul Hamilton, 1911-1963 Collection 1 RG 4/1/5/15 Photographs, 1937-1959 (1.0 Linear Feet)

PART II PERSONAL PAPERS AND ORGANIZATIONAL RECORDS Allen, Paul Hamilton, 1911-1963 Collection 1 RG 4/1/5/15 Photographs, 1937-1959 (1.0 linear feet) Paul Allen was a botanist and plantsman of the American tropics. He was student assistant to C. W. Dodge, the Garden's mycologist, and collector for the Missouri Botanical Garden expedition to Panama in 1934. As manager of the Garden's tropical research station in Balboa, Panama, from 1936 to 1939, he actively col- lected plants for the Flora of Panama. He was the representative of the Garden in Central America, 1940-43, and was recruited after the War to write treatments for the Flora of Panama. The photos consist of 1125 negatives and contact prints of plant taxa, including habitat photos, herbarium specimens, and close-ups arranged in alphabetical order by genus and species. A handwritten inventory by the donor in the collection file lists each item including 19 rolls of film of plant communities in El Salvador, Costa Rica, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama. The collection contains 203 color slides of plants in Panama, other parts of Central America, and North Borneo. Also included are black and white snapshots of Panama, 1937-1944, and specimen photos presented to the Garden's herbarium. Allen's field books and other papers that may give further identification are housed at the Hunt Institute of Botanical Documentation. Copies of certain field notebooks and specimen books are in the herbarium curator correspondence of Robert Woodson, (Collection 1, RG 4/1/1/3). Gift, 1983-1990. ARRANGEMENT: 1) Photographs of Central American plants, no date; 2) Slides, 1947-1959; 3) Black and White photos, 1937-44. -

English Information

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Capitol Reef National Park … the light seems to flow or shine out of the rock rather than to be reflected English from it. – Clarence Dutton, geologist and early explorer of Capitol Reef, 1880s A Wrinkle in the Earth A vibrant palette of color spills across the landscape before bridges, and twisting canyons. Over millions of years geologic forces you. The hues are constantly changing, altered by the play shaped, lifted, and folded the earth, creating this rugged, remote area of light against the towering cliffs, massive domes, arches, known as the Waterpocket Fold. Panorama Point at Sunset Erosion creates waterpockets and potholes that collect The Castle is made of fractured Wingate Sandstone perched upon grey Chinle and red Moenkopi Formations. rainwater and snowmelt, enhancing a rich ecosystem. From the east, the Waterpocket Fold appears as a formidable barrier Capitol Dome reminded early travelers of the US Capitol to travel, much like a barrier reef in an ocean. building and later inspired the name of the park. Creating the Waterpocket Fold Capitol Reef’s defining geologic feature is a wrinkle in Uplift: Between 50 and 70 million years ago, an ancient fault was Earth’s crust, extending nearly 100 miles from Thousand reactivated during a time of tectonic activity, lifting the layers to the Lake Mountain to Lake Powell. It was created over time by west of the fault over 7,000 feet higher than those to the east. Rather three gradual, yet powerful processes—deposition, uplift, than cracking, the rock layers folded over the fault line. -

Pastorale Nureyev Park Appeal Dixie Union Dixieland Band

Consigned by Woodfort Stud 401 401 Gone West Zafonic Iffraaj (GB) Zaizafon BAY FILLY (IRE) Nureyev April 8th, 2011 Pastorale Park Appeal (Third Produce) Dixieland Band Dixie Union Hams (USA) She's Tops (2003) Desert Wine Desert Victress Elegant Victress E.B.F. Nominated. B.C. Nominated. 1st dam HAMS (USA): placed twice at 3; dam of 2 previous foals; 2 runners; 2 winners: Super Market (IRE) (08 f. by Refuse To Bend (IRE)): 4 wins at 2 in Italy. Dixie's Dream (IRE) (09 c. by Hawk Wing (USA)): 2 wins at 2 and 3, 2012 and placed 5 times. 2nd dam DESERT VICTRESS (USA): placed twice at 2 and 3; also winner at 3 in U.S.A. and placed 3 times; dam of 10 foals; 9 runners; 3 winners inc.: DESERT DIGGER (USA) (f. by Mining (USA)): winner at 2 in U.S.A. and £99,649 viz. Sorrento S., Gr.2, placed 5 times inc. 2nd Del Mar Debutante S., Gr.2 and 3rd Princess S., Gr.2; dam of winners inc.: SIRMIONE (USA): won HBPA H. and 2nd Ellis Park Turf S., L. Back Packer (USA): winner in U.S.A., 2nd Transylvania S., L. 3rd dam ELEGANT VICTRESS (CAN) (by Sir Ivor (USA)): 3 wins at 3 in U.S.A. and placed 5 times; dam of 12 foals; 10 runners; 7 winners inc.: EXPLICIT (USA): 6 wins in U.S.A. and £404,504 inc. True North Breeders' Cup H., Gr.2, Count Fleet Sprint H., Gr.3, Pelleteri Breeders' Cup H., L. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Brandon Road: Appendix C

GLMRIS – Brandon Road Appendix C - Risk Assessment August 2017 US Army Corps of Engineers Rock Island & Chicago Districts The Great Lakes and Mississippi River Interbasin Study—Brandon Road Draft Integrated Feasibility Study and Environmental Impact Statement—Will County, Illinois (Page Intentionally Left Blank) Appendix C – Risk Assessment Table of Contents ATTACHMENT 1: PROBABILITY OF ESTABLISHMENT ........... C-2 ATTACHMENT 2: SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS FOR ASIAN CARP POPULATION SIZES ............. C-237 C-1 Attachment 1: Probability of Establishment Introduction This appendix describes the process by which the probabilities of establishment (P(establishment)) for Asian carp (both Bighead and Silver carp) and A. lacustre were estimated, as well as the results of that process. Each species is addressed separately, with the Bighead and Silver carp process described first, followed by the A. lacustre process. Each species narrative is developed as follows: • Estimating P(establishment) • The Experts • The Elicitation • The Model • The Composite Expert • The Results o Probability of Establishment If No New Federal Action Is Taken (No New Federal Action Alternative) o P(establishment) Estimates by expert associated with each alternative Using Individual Expert Opinions o P(establishment) Estimates by alternative Using Individual Expert Opinions • Comparison of the Technology and Nonstructural Alternative to the No New Federal Action Alternative Bighead and Silver Carp Estimating P(establishment) The GLMRIS Risk Assessment provided qualitative estimates of the P(establishment) of Bighead and Silver Carp. The overall P(establishment) was defined in that document as consisting of five probability values using conditional notation: P(establishment) = P(pathway) x P(arrival|pathway) x P(passage|arrival) x P(colonization|passage) x P(spread|colonization) Each of the probability element values assumes that the preceeding element has occurred (e.g. -

The Emergence of Ecology from Natural History Keith R

The emergence of ecology from natural history Keith R. Benson The modern discipline of biology was formed in the 20th century from roots deep in the natural-history tradition, which dates from Aristotle. Not surprisingly, therefore, ecology can also be traced to natural history, especially its 19th-century tradition emphasizing the adaptive nature of organisms to their environment. During the 20th century, ecology has developed and matured from pioneering work on successional stages to mathematically rich work on ecosystem energetics. By the end of the century, ecology has made a return to its natural-history heritage, emphasizing the importance of the integrity of ecosystems in considering human interactions with the environment. Today, the field of biology includes a vast array of diver- like molecular biology, ecology emerged as a distinct gent and unique subdisciplines, ranging from molecular area in biology only at the turn of the century but very biology to comparative endocrinology. With very few quickly developed its own conventions of biological exceptions, most of these specialty areas were created by discourse. Unlike molecular biology and several other biologists during the 20th century, giving modern biology biological subsciplines, ecology’s roots are buried deep its distinctive and exciting character1. However, before within natural history, the descriptive and often romantic 1900, the field was much different because even the term tradition of studying the productions of nature. biology was seldom used2. Indeed, most of those who studied the plants and animals scattered over the earth’s Perspectives on the natural world before the surface referred to themselves as naturalists: students of 20th century natural history3.