Predictive Value of Scoring System in Severe Pediatric Head Injury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glasgow Coma Scale

CalculatedPOWERED BY Decisions Clinical Decision Support for Pediatric Emergency Medicine Practice Subscribers Glasgow Coma Scale Introduction: The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) estimates coma severity based on eye, verbal, and motor criteria. Click the thumbnail above to access the calculator. Points & Pearls • The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) allows provid- agreement between providers, training and ers in multiple settings and with varying levels education are available online from the GCS of training to communicate succinctly about a creators at www.glasgowcomascale.org. patient’s mental status. • Simpler scores that have been shown to per- • The GCS has been shown to have statistical form as well as the GCS in the prehospital and correlation with a broad array of adverse neuro- emergency department setting (for initial evalu- logic outcomes, including brain injury, need for ation); these are often contracted versions of the neurosurgery, and mortality. GCS itself. For example, the Simplified Motor • The GCS score has been incorporated into Score (SMS) uses the motor portion of the GCS numerous guidelines and assessment scores only. THE SMS and other contracted scores are (eg, Advanced Cardiac Life Support, Advanced less well studied than the GCS for outcomes Trauma Life Support, Acute Physiology and like long-term mortality, and the GCS has been Chronic Health Evaluation I-III, the Trauma and studied as trended over time, while the SMS has Injury Severity Score, and the World Federation not. of Neurologic Surgeons Subarachnoid Hemor- rhage Grading Scale) Critical Actions Although it has been adopted widely and in a Points to keep in mind: variety of settings, the GCS score is not intended • Correlation with outcome and severity is most for quantitative use. -

Application of Different Scoring Systems and Their Value in Pediatric

Egyptian Pediatric Association Gazette (2014) 62,59–64 HOSTED BY Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Egyptian Pediatric Association Gazette journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/epag Application of different scoring systems and their value in pediatric intensive care unit Hanaa I. Rady *, Shereen A. Mohamed, Nabil A. Mohssen, Mohamed ElBaz Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt Received 4 September 2014; accepted 28 October 2014 Available online 17 November 2014 KEYWORDS Abstract Background: Little is known on the impact of risk factors that may complicate the Scoring systems; course of critical illness. Scoring systems in ICUs allow assessment of the severity of diseases and Pediatric intensive care unit; predicting mortality. Mortality rate; Objectives: Apply commonly used scores for assessment of illness severity and identify the combi- Critical care; nation of factors predicting patient’s outcome. Illness severity; Methods: We included 231 patients admitted to PICU of Cairo University, Pediatric Hospital. Multiple organ dysfunction PRISM III, PIM2, PEMOD, PELOD, TISS and SOFA scores were applied on the day of admis- sion. Follow up was done using SOFA score and TISS. Results: There were positive correlations between PRISM III, PIM2, PELOD, PEMOD, SOFA and TISS on the day of admission, and the mortality rate (p < 0.0001). TISS and SOFA score had the highest discrimination ability (AUC: 0.81, 0.765, respectively). Significant positive correla- tions were found between SOFA score and TISS scores on days 1, 3 and 7 and PICU mortality rate (p < 0.0001). TISS had more ability of discrimination than SOFA score on day 1 (AUC: 0.843, 0.787, respectively). -

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) Score

CalculatedPOWERED BY Decisions Clinical Decision Support for Emergency Medicine Practice Subscribers Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) Score Introduction: The SOFA score predicts mortality risk for patients in the intensive care unit based on lab results and clinical data. Click the thumbnail above to access the calculator. Points & Pearls • The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment namically or to determine the success or failure of (SOFA) is a mortality prediction score that is an intervention in the ICU. based on the degree of dysfunction of 6 organ systems. • The score is calculated at admission and every Why to Use 24 hours until discharge, using the worst param- The SOFA score can be used to determine the eters measured during the prior 24 hours. level of organ dysfunction and mortality risk in • The scores can be used in several ways, including: ICU patients. » As individual scores for each organ to deter- mine the progression of organ dysfunction. » As a sum of scores on a single intensive care When to Use unit (ICU) day. • The SOFA can be used on all patients who » As a sum of the worst scores during the ICU are admitted to an ICU. stay. • It is not clear whether the SOFA is reliable for • The SOFA score stratifies mortality risk in ICU patients who were transferred from another patients without restricting the data used to ICU. admission values. Critical Actions Instructions Clinical prediction scores such as the SOFA and the Calculate the SOFA score using the worst value Acute Physiologic Assessment and Chronic Health for each variable in the preceding 24-hour Evaluation (APACHE II) can be measured on all period. -

Evaluation and Management of the Polytraumatized Patient in Various Centers

World J. Surg. 7, 143-148, 1983 Wor Journal of Stirgery Evaluation and Management of the Polytraumatized Patient in Various Centers S. Olerud, M.D., and M. Allg6wer, M.D. The Akademiska Sjukhuset Uppsala, Sweden, and the Department of Surgery, Kantonsspital, Basel, Switzerland A questionnaire was sent to the following 6 trauma centers: Paris: Two or more peripheral, visceral, or com- University Hospital for Accident Surgery, Hannover, Fed- plex injuries with respiratory and circulatory fail- eral Republic of Germany (Prof. H. Tscherne); University ure. (This excludes patients who only have sus- of Munich, Department of Surgery, Klinikum Grossha- tained fractures.) dern, Munich, Federal Republic of Germany (Prof. G. Dallas: Multiply injured patient presenting le- Heberer); Akademiska Sjukhuset Uppsala, Sweden (Prof. sions to 2 cavities, associated with 2 or more long S. Olerud); University Hospital, Department of Surgery, bone failures; lesions to 1 cavity associated with 2 Basel, Switzerland (Prof. M. Allgiiwer); H6pital de la Piti~, or more long bone failures; or lesions to multiple Paris, France (Prof. R. Roy-Camille); and University of extremities (at minimum, 3 long bone failures). Texas Southwestern Medical School, Dallas, Texas, U.S.A. (Prof. B. Claudi). Their answers have been summarized in a few short paragraphs where tabulation was not possible, Do You Grade Polytrauma, and If So, How? and then mainly in tabular form for convenient comparison among the various centers. There seems to be considerable international agreement on the main points of early aggres- Hannover: Yes, with our own grading system along sive cardiopulmonary management to prevent multiple with ISS and AIS. -

Trauma Measure #5 Documentation of Glasgow Coma Score at Time of Initial Evaluation in TBI

Trauma Measure #5 Documentation of Glasgow Coma Score at Time of Initial Evaluation in TBI National Quality Strategy Domain: Communication and Care Coordination Measure Type (Process/Outcome): Process 2016 PQRS OPTIONS FOR INDIVIDUAL MEASURES: REGISTRY DESCRIPTION: Percentage of trauma activations for patients aged 18 years or older evaluated as part of a trauma activation or trauma consultation who have a traumatic intracranial hemorrhage on initial head CT for which a Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) at the time of initial evaluation is documented in the medical record within 1 hour of hospital arrival. INSTRUCTIONS: This measure is to be reported each time a patient is evaluated as part of a trauma activation or trauma consultation and is found to have a traumatic intracranial hemorrhage on initial head CT. It is anticipated that clinicians who are responsible for the initial trauma evaluation of TBI patients as specified in the denominator coding will submit this measure. Measure Reporting via Registry: Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) codes, patient demographics, and the medical record are used to identify patients who are included in the measure’s denominator. The listed numerator options are used to report the numerator of the measure. DENOMINATOR: All patients aged 18 years or older evaluated by an eligible professional as part of a trauma activation or trauma consultation who have a traumatic intracranial hemorrhage on initial head CT). Denominator Criteria: Patients aged 18 years or older AND Patients evaluated as part of a trauma activation -

Regional Variability of Admission Prevalence and Mortality of Pediatric Critical Illness in Latvia

Anesth Crit Care 2019; 1 (1): 015-022 DOI: 10.26502/acc.003 Research Article Regional Variability of Admission Prevalence and Mortality of Pediatric Critical Illness in Latvia Linda Setlere1,2, Ivars Vegeris2,3, Margita Stale4, Reinis Balmaks1,2 1Faculty of Medicine, Riga Stradins University, Latvia 2Intensive Care Unit, Children’s Clinical University Hospital, Riga, Latvia 3Department of Doctoral Studies, Riga Stradins University, Latvia 4The Centre for Disease Prevention and Control of Latvia, Riga *Corresponding Author: Dr. Reinis Balmaks, Departments of Clinical Skills and Medical Technologies and Pediatrics, Riga Stradins University, 26a Anninmuizas Blvd, Riga, LV-1067, Latvia, Tel: +37167061579; E-mail: [email protected] Received: 03 May 2019; Accepted: 09 May 2019; Published: 17 May 2019 Abstract Objectives: There is only one pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) in Latvia, where all critically ill children <18 years are admitted from all regions of Latvia. The aim of this study is to ascertain regional differences in mortality and morbidity of critically ill children over a 5-year period. Materials and Methods: Descriptive retrospective study of children who were admitted to the PICU in Latvia from January 2012 to December 2016. Data on episodes were obtained from the Children's Clinical University Hospital electronic health records. Pediatric Index of Mortality (PIM2) was used for risk adjustment and calculation of standardized mortality ratio (SMR). The data were compared among the six regions of Latvia - Kurzeme, Latgale, Pieriga, Riga, Vidzeme, and Zemgale. Results: The analysis included 3651 intensive care episodes. The highest PICU admission prevalence was in Riga and the lowest in Latgale - 2.3 and 1.7 admissions per 1000 children per year, respectively. -

On-Line Table 1: Clinical, EEG, and Perfusion Data of Patients with NCSE Age Pre- Lat Signs/ Perfusion (Visual Seizure No

On-line Table 1: Clinical, EEG, and perfusion data of patients with NCSE Age Pre- Lat Signs/ Perfusion (visual Seizure No. (yr) Sex seizure Jerks GCS Ventilation EEG analysis) Classification Epilepsy Comorbidity Survival 1.1 59 M Coma R/Ϫ 6 ϩ SW Hyperperfusion Ins L Coma with NCSE – Cardiac arrest – FT L 1.2 72 F GTCS L/Ϫ 3 ϩ SW Hyperperfusion SSE ϩ Chronic infarction L ϩ PR PR 1.3 60 F GTCS No/Ϫ 3 ϩ SW Hyperperfusion SSE ϩ Traumatic brain injury ϩ FR FR 1.4 72 F GTCS R/ϩ 7 – SW Hyperperfusion SSE ϩ Chronic infarction L – TL TL 1.5 89 F GTCS L/Ϫ 8 – SW Hyperperfusion SSE ϩ Chronic infarction R – FR FR 1.6 67 F CP No/ϩ 11 – SW No Hyperperfusion CPSE ϩ Chronic infarction L ϩ FL 1.7 62 F GTCS R/Ϫ 5 ϩ SW Hyperperfusion SSE – Meningo-encephalitis – FR Ins,TL 1.8 67 M GTCS R/ϩ 5 ϩ SL Hyperperfusion SSE – Subacute SDH L ϩ FP L Ins L 1.9 63 F CP L/Ϫ 11 – SW No hyperperfusion CPSE ϩ Chronic infarction L ϩ TP L Note:—Lat indicates lateralizing; Pre, preceding: R, right; L, left; SW, spike-wave activity; F, frontal; T, temporal; P, parietal; Ins, insular; SDH, subdural hemorrhage; SL, slowing; EEG, electroencephalography; NCSE, nonconvulsive status epilepticus; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; GTCS, generalized tonic-clonic seizure; CP, complex-partial; CPSE, complex-partial status epilepticus; SSE, subtle status epilepticus. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol ͉͉www.ajnr.org E1 On-line Table 2: Clinical, EEG, and perfusion data of patients with a postictal state Age Pre- Lat Perfusion (visual No. -

Development of a Large Animal Model of Lethal Polytrauma and Intra

Open access Original research Trauma Surg Acute Care Open: first published as 10.1136/tsaco-2020-000636 on 1 February 2021. Downloaded from Development of a large animal model of lethal polytrauma and intra- abdominal sepsis with bacteremia Rachel L O’Connell, Glenn K Wakam , Ali Siddiqui, Aaron M Williams, Nathan Graham, Michael T Kemp, Kiril Chtraklin, Umar F Bhatti, Alizeh Shamshad, Yongqing Li, Hasan B Alam, Ben E Biesterveld ► Additional material is ABSTRACT abdomen and pelvic contents. The same review published online only. To view, Background Trauma and sepsis are individually two of showed that of patients with whole body injuries, please visit the journal online 1 (http:// dx. doi. org/ 10. 1136/ the leading causes of death worldwide. When combined, 37.9% had penetrating injuries. The abdomen is tsaco- 2020- 000636). the mortality is greater than 50%. Thus, it is imperative one area of the body which is particularly suscep- to have a reproducible and reliable animal model to tible to penetrating injuries.2 In a review of patients Surgery, Michigan Medicine, study the effects of polytrauma and sepsis and test novel in Afghanistan with penetrating abdominal wounds, University of Michigan, Ann treatment options. Porcine models are more translatable the majority of injuries were to the gastrointes- Arbor, Michigan, USA to humans than rodent models due to the similarities tinal tract with the most common injury being to 3 Correspondence to in anatomy and physiological response. We embarked the small bowel. While this severe constellation Dr Glenn K Wakam; gw akam@ on a study to develop a reproducible model of lethal of injuries is uncommon in the civilian setting, med. -

Renal Endocrine Manifestations During Polytrauma: a Cause of Concern for the Anesthesiologist

Review Article Renal endocrine manifestations during polytrauma: A cause of concern for the anesthesiologist Sukhminder Jit Singh Bajwa, Ashish Kulshrestha Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Gian Sagar Medical College and Hospital, Ram Nagar, Banur, Punjab, India ABSTRACT Nowadays, an increasing number of patients get admitted with polytrauma, mainly due to road traffic accidents. These polytrauma victims may exhibit associated renal injuries, in addition to bone injuries and injuries to other visceral organs. Nevertheless, even in cases of polytrauma, renal tissue is hyperfunctional as part of the normal protective responses of the body to external insults. Both polytrauma and renal injuries exhibit widespread renal, endocrine, and metabolic responses. The situation is very challenging for the attending anesthesiologist, as he is expected to contribute immensely, not only in the resuscitation of such patients, but if required, to allow the operative procedures in case of life-threatening injuries. During administration of anesthesia, care has to be taken, not only to maintain hemodynamic stability, but equal attention has to be paid to various renal protection strategies. At the same time, various renoendocrine manifestations have to be taken into account, so that a judicious use of anesthesia drugs can be made, to minimize the renal insults. Key words: Anesthesia, polytrauma, renal injuries, renal protection, renoendocrine manifestations INTRODUCTION trauma are also one of the major protective responses exerted by the body to maintain a normal metabolic and Major trauma is a pathophysiological state that threatens endocrine milieu. The caloric substitutes are mobilized so [2] the integrity of the internal environment, causing alteration that supply of glucose to the vital organs is maintained. -

Prehospital Determination of Tracheal Tube Placement in Severe Head Injury

518 PREHOSPITAL CARE Prehospital determination of tracheal tube placement in severe head injury Emerg Med J: first published as on 18 June 2004. Downloaded from Sˇ Grmec, Sˇ Mally ............................................................................................................................... Emerg Med J 2004;21:518–520. doi: 10.1136/emj.2002.001974 Objectives: The aim of this prospective study in the prehospital setting was to compare three different methods for immediate confirmation of tube placement into the trachea in patients with severe head injury: auscultation, capnometry, and capnography. Methods: All adult patients (.18 years) with severe head injury, maxillofacial injury with need of protection of airway, or polytrauma were intubated by an emergency physician in the field. Tube position was initially evaluated by auscultation. Then, capnometry and capnography was performed (infrared method). Emergency physicians evaluated capnogram and partial pressure of end tidal carbon dioxide See end of article for (EtCO2) in millimetres of mercury. Determination of final tube placement was performed by a second direct authors’ affiliations ....................... visualisation with laryngoscope. Data are mean (SD) and percentages. Results: There were 81 patients enrolled in this study (58 with severe head injury, 6 with maxillofacial Correspondence to: trauma, and 17 politraumatised patients). At the first attempt eight patients were intubated into the ˇ Dr S Mally, Zdravstveni oesophagus. Afterwards endotracheal intubation was undertaken in all without complications. The initial Dom, dr Adolfa Droica, Ulica talcev 9, Maribor, capnometry (sensitivity 100%, specificity 100%), capnometry after sixth breath (sensitivity 100%, specificity Slovenia; stefan.mally@ 100%), and capnography after sixth breath (sensitivity 100%, specificity 100%) were significantly better guest.arnes.si indicators for tracheal tube placement than auscultation (sensitivity 94%, specificity 66%, p,0.01). -

Pediatric Index of Mortality 2 Score As an Outcome Predictor in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit in India

Research Article Pediatric index of mortality 2 score as an outcome predictor in pediatric Intensive Care Unit in India Jeyanthi Gandhi, Shanthi Sangareddi, Poovazhagi Varadarajan, Saradha Suresh Background and Aims: Pediatric index of mortality (PIM) 2 score is one of the severity Access this article online scoring systems being used for predicting outcome of patients admitted to intensive Website: www.ijccm.org care units (ICUs). The aim of the present study was to evaluate the usefulness of PIM2 DOI: 10.4103/0972-5229.120320 score in predicting mortality in a tertiary care pediatric ICU (PICU) and to assess the Quick Response Code: Abstract associated factors in predicting mortality such as presence of shock, need for assisted ventilation and Glasgow coma scale <8. Materials and Methods: This was a prospective observation study done at tertiary care PICU from May 2011 to July 2011. Consecutive 119 patients admitted to PICU (aged 1 month to 12 years) were enrolled in the study. PIM2 scoring was done for all patients. The outcome was recorded as death or discharge. The associated factors for mortality were analyzed with SPSS 17. Results: PIM2 score discriminated between death and survival at a 99.8 cut-off, with area under receiver operating characteristic curve 0.843 with 95% confi dence interval (CI) (0.765, 0.903). Most patients were referred late to this hospital, which explains higher death rate (46.2%), lesser length of hospital stay (mean 2.98 days) in the mortality group, and increased rate of mechanical ventilation (68.1%). Presence of shock was independently associated with mortality, as evidenced by binary logistic regression. -

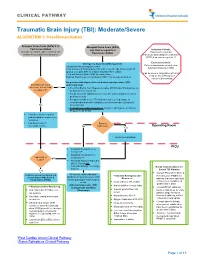

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI): Moderate/Severe ALGORITHM 1: Post-Resuscitation

CLINICAL PATHWAY Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI): Moderate/Severe ALGORITHM 1: Post-Resuscitation Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) 9-12 Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) Post resuscitation less than or equal to 8 Inclusion Criteria: (Consider for children under 2 years old with Post-resuscitation Patient with traumatic concern for acute abusive head trauma) brain injury and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) less than or equal to 12 Exclusion Criteria: Emergency Department Management Patients found down without clear Trauma and Neurosurgery Consult traumatic brain injury (TBI) Head Computed Tomography (CT) scan- if not already obtained (STAT upload) or a quick MRI as a viable (radiation-free) option (Can be used in conjunction with Post 2 IVs with Normal Saline (NS) as maintenance Cardiac Arrest Pathway if Modified Rapid sequence intubation (RSI) if not already performed considered beneficial) For patients with signs of elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) Monitor GCS. GCS empirically treat decrease to less than Yes • 3% (0.5 mEq/mL Na+) Hypertonic saline (HTS) bolus 5mL/kg/dose via or equal to 8? peripheral IV or central line • For patients with ongoing seizures use the status epilepticus clinical pathway (below). • For patients with severe TBI who have not received a dose of levetiracetam at another institution, give levetiracetam 20mg/kg IV No (max 2 grams) • If transporting to Operating Room: Consider mild hyperventilation to PCO2 of 32-35 mmHg • Consider comfort sedation and standard neuroprotective measures. • Complete frequent Surgery neurologic exams. No Indicated?