Hiq V. Linkedin: a Clash Between Privacy and Competition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Mentioning of Urgent Matters Will Be Before Hon'ble DB-I at 10.30 A.M

09.07.2018 SUPPLEMENTARY LIST SUPPLEMENTARY LIST FOR TODAY IN CONTINUATION OF THE ADVANCE LIST ALREADY CIRCULATED. THE WEBSITE OF DELHI HIGH COURT IS www.delhihighcourt.nic.in INDEX PRONOUNCEMENT OF JUDGMENTS -----------------> 01 TO REGULAR MATTERS ----------------------------> 01 TO 102 FINAL MATTERS (ORIGINAL SIDE) --------------> 01 TO 11 ADVANCE LIST -------------------------------> 01 TO 87 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)---------> 88 TO 125 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST-MID)---------> 126 TO 146 SECOND SUPPLEMENTARY -----------------------> 147 TO 156 ORIGINAL SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY I)-------------> 157 TO 167 COMPANY ------------------------------------> 168 TO 170 MEDIATION CAUSE LIST -----------------------> 01 TO 03 PRE LOK ADALAT LIST ------------------------> 01 TO 02 THIRD SUPPLEMENTARY -----------------------> TO NOTES 1. Mentioning of urgent matters will be before Hon'ble DB-I at 10.30 A.M.. 2. Hon'ble Mr. Justice Vinod Goel will hear single bench matters listed before his Lordship in Court No.36. In view of the Notification No.F.No.6/18/2018-judl./827- 830 dated 4th July, 2018 issued by the Govt. of National Capital Territory of Delhi, (Department of Law, Justice & Legislative Affairs) in pursuance of the Commercial Courts, Commercial Division and Commercial Appellate Division of High Courts(Amendment) Ordinance, 2018, Hon'ble the Action Chief Justice has been pleased to order that the Registry of this Court will, forthwith, not accept any further commercial suits valued at less than rupees two crores. DELETIONS 1. FAO(OS) 108/2018 listed before Hon'ble DB-I at item No.29 is deleted as the same is fixed for 13.07.2018. 2. LA.APPL. 227/2015 listed before Hon'ble Mr. Justice Rajiv Sahai Endlaw at item No.5 is deleted as the same is listed before Sh. -

Hon'ble Ms. Justice Gita Mittal

Hon’ble Ms. Justice Gita Mittal Justice Gita Mittal was born on 9th December, 1958 to parents who were in academics. An alumna of the Lady Irwin Higher Secondary School [Science batch of 1975], Lady Shri Ram College For Women [BA (Eco. Hons.) 1978] and the Campus Law Centre, Delhi University [(LL.B) 1981], she was appointed as an Additional Judge of Delhi High Court on 16th July, 2004. Prior to her appointment as Additional Judge, she had an illustrious legal practice in all courts and other judicial forums since 1981. Justice Mittal was confirmed as a permanent judge on the 20th of February, 2006. As a judge, she has presided over several jurisdictions including heading a Division Bench hearing criminal appeals involving life and death sentence references; matters of the Armed Forces; Cooperative Societies; Criminal Contempt References; Criminal Appeals; Death References; Company Appeals; Writ Petitions and Letters Patent Appeals relating to the Armed Forces. She currently presides over a Division Bench hearing writ petitions arising out of orders of the Central Administrative Tribunal and other service matters. Since August, 2008, Justice Gita Mittal has been a member of the Governing Council of the National Law University, Delhi. She is also a member of the Governing Council of the Indian Law Institute, New Delhi since 2013 and has been nominated to its Administrative Committee. Justice Mittal is presently chairing the court committees on the Delhi High Court’s Mediation and Conciliation Centre as well as the committee monitoring the Implementation of Judicial Guidelines for Dealing with Cases of Sexual Offences and Child Witnesses. -

CURRICULAM VITAE Dr. Soumita Basu Mailing Address: South Asian

CURRICULAM VITAE Dr. Soumita Basu Mailing Address: South Asian University Assistant Professor Room 221, Akbar Bhawan, Chanakyapuri Department of International Relations New Delhi – 110021 South Asian University Phone: 01124122512 (ext. 211) New Delhi, India Email: [email protected] Areas of expertise: UN Security Council Resolutions on Women and Peace and Security; Feminist International Relations; United Nations; South Asian Participation in UN Peace Operations; Critical Security Studies ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Assistant Professor, Department of International Relations South Asian University, India 2011-Ongoing Kenyon-Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow & Visiting Assistant Professor of International Studies, Kenyon College, USA 2010-2011 Hayward R. Alker Post-doctoral Fellow (Gender & Global Politics) University of Southern California, Los Angeles, USA 2009-2010 Part-time Teaching Staff, Department of International Politics University of Wales, Aberystwyth, UK 2005-2008 Visiting Faculty, Department of Journalism Lady Shri Ram College, University of Delhi, India July 2005 UNIVERSITY EDUCATION PhD International Politics, Aberystwyth University, UK 2005-2009 Dissertation: Security through Transformations: The Case of the Passage of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women and Peace and Security (EH Carr Doctoral Scholarship) MSc International Relations, University of Bristol, UK 2001-2002 Dissertation: Mapping Security for Citizens of ‘Landless States’ (DFID and University of Bristol Shared Scholarship) BA (Hons.) Journalism, Lady Shri Ram College, -

First Admission List - M.A

First Admission List - M.A. English Category : UNRESERVED (Entrance Based) # Roll No. Form No. Name Alloted Department/College 1 160815834 16ENGL1044205 DEBANGANA PAL Miranda House 2 160815171 16ENGL1133358 Alex John Joseph Kirori Mal College 3 160810398 16ENGL1017134 Avali Gandharva Lady Shri Ram College for Women 4 160815671 16ENGL1073063 Meenakshi Sharma Ramjas College 5 160813209 16ENGL1028713 Swarnima Dharwal Daulat Ram College 6 160814895 16ENGL1113183 Arpita Sen Hans Raj College 7 160816164 16ENGL1022555 Madhurima Sen Miranda House 8 160811195 16ENGL1081884 Asmita Jain Miranda House 9 160812459 16ENGL1009862 PARTH DUA Hans Raj College 10 160813863 16ENGL1075598 Prachi Gupta Lady Shri Ram College for Women 11 160815763 16ENGL1033269 DEBAPARNA MUKHERJEE Jesus & Mary College 12 160812335 16ENGL1099053 VANYA GOYAL Sri Venkateswara College 13 160815919 16ENGL1075971 PARAMIKA BANERJEE Hans Raj College 14 160812690 16ENGL1106175 Jasmine Bhalla Kirori Mal College 15 160813799 16ENGL1027835 Vinayak Gaurav Pant Ramjas College 16 160811698 16ENGL1073268 Avani Jayant Udgaonkar Daulat Ram College 17 160813961 16ENGL1039290 KIRAN YADAV Ramjas College 18 160814958 16ENGL1095185 Anibal Goth Kirori Mal College 19 160812174 16ENGL1050583 STUTI LOKESH SHARMA Kirori Mal College 20 160810271 16ENGL1093659 riya mishra Daulat Ram College 21 160810588 16ENGL1031232 Richa Thakur Jesus & Mary College 22 160812261 16ENGL1098555 Sohina Sharma Sri Guru Teg Bahadur Khalsa College 23 160815918 16ENGL1004389 Supratik Ray Sri Venkateswara College 24 160816208 -

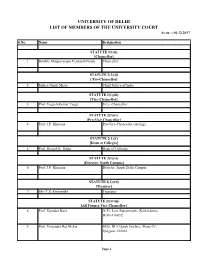

UNIVERSITY of DELHI LIST of MEMBERS of the UNIVERSITY COURT As on :- 04.12.2017

UNIVERSITY OF DELHI LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE UNIVERSITY COURT As on :- 04.12.2017 S.No. Name Designation STATUTE 2(1)(i) [Chancellor] 1 Hon'ble Muppavarapu Venkaiah Naidu Chancellor STATUTE 2(1)(ii) [ Pro-Chancellor] 2 Justice Dipak Misra Chief Justice of India STATUTE 2(1)(iii) [Vice-Chancellor] 3 Prof. Yogesh Kumar Tyagi Vice -Chancellor STATUTE 2(1)(iv) [Pro-Vice-Chancellor] 4 Prof. J.P. Khurana Pro-Vice-Chancellor (Acting) STATUTE 2(1)(v) [Dean of Colleges] 5 Prof. Devesh K. Sinha Dean of Colleges STATUTE 2(1)(vi) [Director, South Campus] 6 Prof. J.P. Khurana Director, South Delhi Campus STATUTE 2(1)(vii) [Tresurer] 7 Shri T.S. Kripanidhi Treasurer STATUTE 2(1)(viii) [All Former Vice-Chancellor] 8 Prof. Upendra Baxi A-51, Law Appartments, Karkardoma, Delhi-110092 9 Prof. Vrajendra Raj Mehta 5928, DLF Qutab Enclave, Phase-IV, Gurgaon-122002 Page 1 10 Prof. Deepak Nayyar 5-B, Friends Colony (West), New Delhi-110065 11 Prof. Deepak Pental Q.No. 7, Ty.V-B, South Campus, New Delhi-110021 12 Prof. Dinesh Singh 32, Chhatra Marg, University of Delhi, Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(ix) [Librarian] 13 Dr. D.V. Singh Librarian STATUTE 2(1)(x) [Proctor] 14 Prof. Neeta Sehgal Proctor (Offtg.) STATUTE 2(1)(xi) [Dean Student's Welfare] 15 Prof. Rajesh Tondon Dean Student's Welfare STATUTE 2(1)(xii) [Head of Departments] 16 Prof. Christel Rashmi Devadawson The Head Department of English University of Delhi Delhi-110007 17 Prof. Sharda Sharma The Head Department of Sanskrit University of Delhi Delhi-110007 18 Prof. -

Shri Ram College of Commerce

SHRI RAM COLLEGE OF COMMERCE UNIVERSITY OF DELHI MAURICE NAGAR, DELHI-110007 SELF STUDY REPORT 2015 SUBMITTED TO NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL BENGALURU SHRI RAM COLLEGE OF COMMERCE SELF STUDY REPORT 2015 CONTENTS 1. Preface ii 2. Acknowledgement iv 3. List of Abbreviations v 4. Executive Summary: SWOC Analysis 2 5. Criteria-wise Executive Summary 13 6. Profile of the College 22 7. Criteria-wise Analytical Report a. Criterion I: Curricular Aspects 35 b. Criterion II: Teaching-Learning and Evaluation 53 c. Criterion III: Research, Consultancy and Extension 86 d. Criterion IV: Infrastructure and Learning Resources 132 e. Criterion V: Student Support and Progression 156 f. Criterion VI: Governance, Leadership and Management 215 g. Criterion VII: Innovations and Best Practices 262 8. Evaluative Reports of the Departments a. Department of Commerce 285 b. Department of Economics 314 SHRI RAM COLLEGE OF COMMERCE Page i PREFACE Shri Ram College of Commerce, for last ninety years, has been a top ranked undergraduate college of commerce and economics developing leaders with a global mindset, business skills, a sense of social responsibility and human touch. The College is the first choice of undergraduate students seeking to gain the skills necessary for success in contemporary global business world. The focus of the Institution is on nurturing students, sharpening their skills, building their foundation of knowledge and facilitating the learning they need to take their career to the highest level and to cultivate the practice of looking beyond oneself for sustainable happiness. The College epitomises the philosophy embedded in the divine words of Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore. -

Over 500 Academicians, Activists, Artists and Writers Including Eminent Professors Noam Chomsky, Gayatri Spivak, Barbara Hariss

Over 500 academicians, activists, artists and writers including eminent Professors Noam Chomsky, Gayatri Spivak, Barbara Hariss-White, Michael Davis among others condemn the ongoing state violence and unlawful detention of faculty and student protesters of the University of Hyderabad. We, academicians, activists, artists and writers, condemn the ongoing brutal attacks on and unlawful detention of peacefully protesting faculty and students at the University of Hyderabad by the University administration and the police. We also condemn the restriction of access to basic necessities such as water and food on campus. The students and faculty members of the University of Hyderabad were protesting the reinstatement of Dr. Appa Rao Podile as the Vice-Chancellor despite the ongoing judicial enquiry against him related to the circumstances leading to the death of the dalit student Rohith Vemula on January 17th, 2016. Students and faculty members of the university community are concerned that this may provide him the opportunity to tamper with evidence and to influence witnesses. Suicides by dalit students have been recurring in the University of Hyderabad and other campuses across the country. The issue spiraled into a nationwide students’ protest with the death of the dalit scholar Rohith Vemula. The protests have pushed into the foreground public discussion and debate on the persistence of caste-based discrimination in educational institutions, and surveillance and suppression of dissent and intellectual debate in university spaces. Since the morning of March 22 when Dr. Appa Rao returned to campus, the students and staff have been in a siege-like situation. The peacefully protesting staff and students were brutally lathi-charged by the police, and 27 people were taken into custody. -

AQAR-2018-KNC-DU-2.Pdf

Kamala Nehru College University of Delhi NAAC Accredited ‘A’ Grade Annual Quality Assurance Report 2018 The Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) of the IQAC Part A 1. Details of the Institution 1.1 Name of the Institution Kamala Nehru College 1.2 Address Line 1 August Kranti Marg Address Line 2 Siri Fort Road City/Town New Delhi State Delhi Pin Code 110049 Institution e-mail address [email protected] Contact Nos. 011-26494881 Name of the Head of the Institution: Dr. Kalpana Bhakuni Tel. No. with STD Code: 011-26495964 Mobile: Mr. K. Ramesh (Admin. Officer) - 09811880906 Name of the IQAC Co-ordinator: Dr. Geetesh Nirban Mobile: 09811423241 IQAC e-mail address: [email protected] 1.3 NAAC Track ID(For ex. MHCOGN 18879) DLCOGN22288 OR 1.4NAAC Executive Committee No. & Date: EC (SC)/18/A&A/15.1, DATE: NOV.05, 2016 1.5 Website address: www.knc.edu.in Web-link of the AQAR: https://www.knc.edu.in/document/AQAR- 2018-KNC-DU-2.pdf AQAR-2018 | Kamala Nehru College | University of Delhi Page | 1 1.6 Accreditation Details Year of Validity Sl. No. Cycle Grade CGPA Accreditation Period 04.11.202 1 1st Cycle A 3.33 2016 1 2 2nd Cycle 3 3rd Cycle 4 4th Cycle 1.7 Date of Establishment of IQAC: 2016 1.8 Details of the previous year’s AQAR submitted to NAACafterthe latest Assessment and Accreditation by NAAC ((for example AQAR 2010-11submitted to NAAC on 12-10-2011) i. AQAR July 2016- June 2017 submitted to NAAC on 13/05/2018 1.9 Institutional Status: University State Central √ Deemed Private Affiliated College Yes No √ Constituent College -

Archives, Archeology, Art and Culture

Focal theme: Department of Art, Culture and Language under the Delhi governance. Sub-theme: An analytical study on Conservation of Heritage Sites in Delhi and Study of Library and Museum. Working Paper No. 209 Summer Research Internship 2009 Centre for Civil Society Chitra Mishra [Second Year, B.A. (Honors) History, Lady Shri Ram College for Women, University of Delhi] This working paper was written at Centre for Civil Society (CCS) summer internship 2009. The author expresses their sincere gratitude to CCS for giving them this opportunity of working with them. 1 CONTENTS. SECTION- A. INTRODUCTION HISTORY OF DELHI DEPARTMENT OF ART, CULTURE AND LANGUAGE BUDGET FOR ANNUAL PLAN SECTION- B LIBRARY- A HISTORY. DELHI PUBLIC LIBRARY. SECTION – C LAW OF CONSERVATION POLICY WHO IS RESPONSIBLE FOR CONVERSATION? DELHI MASTERPLAN 2021. CASE STUDY- SHAHJAHANABAD. CONSERVATION FROM THEORITICAL PERSPECTIVE. AUTHORITIES TAKE ON THE ISSUE. TOURISM- A COLLABORATION. AN ANALYSIS- COMPARISION BETWEEN INDIA AND USA. SECTION - D. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS. REFERENCES 2 INTRODUCTION: According to writer William Darlymple, "only Rome, Istanbul and Cairo can even begin to rival Delhi for the sheer volume and density of historic remains". Delhi is a historical city whose remnants are spread right from Mehrauli to Shahjahanabad. Large number of monuments are scattered all over Delhi. The built heritage of Delhi is an irreplaceable and nonrenewable cultural resource. Besides being part of life for many, it has educational, recreational and major tourism potential. It enhances Delhi’s environment, giving it identity and character. It encompasses culture, lifestyles, design, materials, engineering and architecture. The Heritage Resources include symbols of successive civilizations and cities that came up over the millennia, historic buildings and complexes, historical gardens, water engineering structures and their catchments, the remains of fortified citadels, places for worship and for the deceased, historic cities and villages, unearthed heritage and their components. -

RPS Infinia - Mathura Road, Faridabad Office Spaces in NH-2, Mathura Road, Faridabad

https://www.propertywala.com/rps-infinia-faridabad RPS Infinia - Mathura Road, Faridabad Office spaces in NH-2, Mathura Road, Faridabad. RPS Group presents beautiful office spaces in RPS Infinia at NH-2, Mathura Road, Faridabad. Project ID : J119001901 Builder: RPS Group Properties: Office Spaces Location: RPS Infinia, Mathura Road area, Faridabad (Haryana) Completion Date: Jan, 2015 Status: Started Description A well-known name in the field of real estate and development is RPS Group and this leading real estate group is offering beautiful office spaces in RPS Infinia that is located in one of the very beautiful location that is NH-2, Mathura Road, Faridabad. RPS Infinia is one of the very special commercial project of its builder and when you will come to see the project then you will find that every office is designed and developed very carefully. RPS INFINIA provides the best-in-class work atmosphere to the table with advantages & comforts that will bring a smile to your face. From the moment you enter as well as are welcomed by luscious greens to the time you step into any of the buildings that look & feel a class apart, RPS INFINIA creates work feel like it should, a home away from home. Location - NH-2, Mathura Road, Faridabad Type - Office Spaces Price - On Request Highlight At Main Mathura Road (NH-2)-At Tip Of South Delhi Most Strategic Location 1000000 sqft Built-up Area-office, Bussiness Suits, Retail & More Freehold Project Development 3 Level Integrated Basement Car Parking Aprox. 200 Mtr. Away from Sarai Metro Station Features -

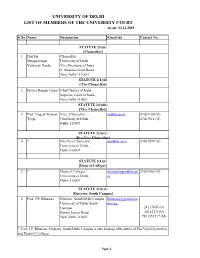

UNIVERSITY of DELHI LIST of MEMBERS of the UNIVERSITY COURT As On: 12.11.2018

UNIVERSITY OF DELHI LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE UNIVERSITY COURT As on: 12.11.2018 S.No Name Designation Email ids Contact No. STATUTE 2(1)(i) [Chancellor] 1 Hon'ble Chancellor Muppavarapu University of Delhi Venkaiah Naidu Vice-President of India 6, Maulana Azad Road, New Delhi - 110011 STATUTE 2(1)(ii) [ Pro-Chancellor] 2 Justice Ranjan Gogoi Chief Justice of India Supreme Court of India New Delhi-110001 STATUTE 2(1)(iii) [Vice-Chancellor] 3 Prof. Yogesh Kumar Vice -Chancellor [email protected] 27001100 (O) Tyagi University of Delhi, 27667011 (O) Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(iv) [Pro-Vice-Chancellor] 4 * Pro-Vice-Chancellor [email protected] 27667899 (O) University of Delhi, Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(v) [Dean of Colleges] 5 * Dean of Colleges [email protected]. 27667066 (O) University of Delhi, in Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(vi) [Director, South Campus] 6 Prof. J.P. Khurana Director, South Delhi Campus khuranaj@genomein University of Delhi South dia.org Campus 24117005 (O) Benito Jaurez Road 24112231(O) New Delhi-110021 9811351217 (M) * Prof. J.P. Khurana, Director, South Delhi Campus is also looking after duties of Pro-Vice-Chancellor and Dean of Colleges Page 1 STATUTE 2(1)(vii) [Tresurer] 7 Shri T.S. Kripanidhi Treasurer kripanidhits@yahoo. 9818928162 University of Delhi co.in Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(viii) [All Former Vice-Chancellor] 8 Prof. Upendra Baxi A-51, Law Appartments, [email protected] 8447944106 (M) Karkardoma, n Delhi-110092 baxiupendra@gmail. 9 Prof. Vrajendra Raj 5928, DLF Qutab Enclave, 9350292197 (M) Mehta Phase-IV, Gurgaon-122002 10 Prof. -

Farewell Speech on the Retirement of Justice Pratibha Rani 24.08.2018

FAREWELL SPEECH ON THE RETIREMENT OF JUSTICE PRATIBHA RANI 24.08.2018 My esteemed sister and brother colleagues, Ms. Maninder Acharya, Additional Solicitor General of India, Mr. K.C. Mittal ,President, Bar Council of Delhi Mr. Kirti Uppal, President Delhi High Court Bar Association, Mr. J.P. Sengh, Vice‐President, Delhi High Court Bar Association, Mr. Amit Sharma, Secretary, Delhi High Bar Association, Mr. Ramesh Singh, Standing Counsel, (Civil), Govt. of NCT of Delhi, Mr. Rahul Mehra, Standing Counsel, (Criminal) Govt. of NCT of Delhi, Other Standing Counsels of the Central and State Government, Executive Members of the Delhi High Court Bar Association, President, Secretary and Office bearers of all the Bar Associations of Delhi. Secretary and Office bearers of the Bar Council of Delhi., Senior Advocates, Learned Members of the bar, Family Members of Justice Pratibha Rani And every one present… We have assembled here this afternoon to bid farewell to one of our dear Colleagues Justice Pratibha Rani who demits office on superannuation after a distinguished and fulfilling career. Justice Pratibha Rani was Born on 25th August, 1956 in Delhi. On completing her schooling from Delhi, she studied at Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi University in 1975. She obtained her LL.B. degree from Law Faculty, Delhi University in 1978. Justice Pratibha Rani joined Delhi Judicial Service in 1979. She worked as a Metropolitan Magistrate, Civil Judge, and also as the Presiding Officer of the Labour Court before being promoted to the Delhi Higher Judicial Service in July, 1996. Justice Pratibha Rani has worked as Special Judge (NDPS), Additional District and Sessions Judge, Special Judge (CBI) and District Judge, Incharge ASJ and became the District and Sessions Judge, Delhi on 1st March, 2011.