Gang Activity: a Deeper Analysis Into the Types of Crime Committed By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White Supremacist Prison Gangs in the United States a Preliminary Inventory Introduction

White Supremacist Prison Gangs in the United States A Preliminary Inventory Introduction With rising numbers and an increasing geographical spread, for some years white supremacist prison gangs have constitut- ed the fastest-growing segment of the white supremacist movement in the United States. While some other segments, such as neo-Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan, have suffered stagnation or even decline, white supremacist prison gangs have steadily been growing in numbers and reach, accompanied by a related rise in crime and violence. What is more, though they are called “prison gangs,” gangs like the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas, Aryan Circle, European Kindred and others, are just as active on the streets of America as they are behind bars. They plague not simply other inmates, but also local communities across the United States, from California to New Hampshire, Washington to Florida. For example, between 2000 and 2015, one single white supremacist prison gang, the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas, was responsible for at least 33 murders in communities across Texas. Behind these killings were a variety of motivations, including traditional criminal motives, gang-related murders, internal killings of suspected informants or rules-breakers, and hate-related motives directed against minorities. These murders didn’t take place behind bars—they occurred in the streets, homes and businesses of cities and towns across the Lone Star State. When people hear the term “prison gang,” they often assume that such gang members plague only other prisoners, or perhaps also corrections personnel. They certainly do represent a threat to inmates, many of whom have fallen prey to their violent attacks. -

Download Kentucky Indictment

Case: 7:20-cr-00017-REW-EBA Doc #: 1 Filed: 09/03/20 Page: 1 of 13 - Page ID#: 1 Eastern D!Jtrict of Kentucky FILED UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF KENTUCKY SEP O3 2020 SOUTHERN DIVISION AT LEXINGTON PIKEVILLE ROBERT R. CARR CLERK U.S. DISTRICT COURT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. INDICTMENT NO. 7:z.5-02.-lJ-(<'i)AJ MITCHELL FARKAS, UNDER SEAL aka LIFTER, JONATHAN GOBER, aka TUCKER, JAMES POOLE, aka REDWOOD, and ANDREW TINLIN, aka TIN * * * * * THE GRAND JURY CHARGES: GENERAL ALLEGATIONS Indictment 1. At all times relevant to this Indictment, the defendants, MITCHELL FARKAS, aka LIFTER, JONATHAN GOBER, aka TUCKER, JAMES POOLE, aka REDWOOD, ANDREW TINLIN, aka TIN, and others, known and unknown, were members of the Aryan Circle (hereinafter the "AC"), a criminal organization whose members and associates engaged in narcotics distribution, firearms trafficking, and acts of violence including acts involving murder, assault, robbery, witness intimidation, and kidnapping. At all times relevant to this Indictment, the AC operated throughout Kentucky, Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, Indiana, New Jersey, and Arizona, 1 Case: 7:20-cr-00017-REW-EBA Doc #: 1 Filed: 09/03/20 Page: 2 of 13 - Page ID#: 2 including in the Eastern District of Kentucky, and elsewhere. Structure and Operation of the Enterprise 2. The structure and operation of the AC included, but was not limited to, the following: a. The AC was a violent, race-based, "whites only" prison-based gang with hundreds of members operating inside and outside of state and federal penal institutions throughout Kentucky, Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, Indiana, New Jersey, and Arizona. -

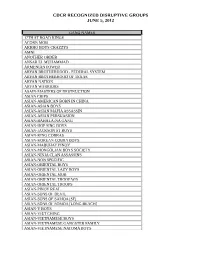

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

What Have We Learned About Prison Gangs? Findings from the Lonestar Project

What have we learned about prison gangs? Findings from the LoneStar Project David C. Pyrooz, Ph.D. Department of Sociology Institute of Behavioral Science University of Colorado Boulder A Presentation to the UTEP Center for Law & Human Behavior Email: [email protected] Phone: (303) 492-3241 The LoneStar Project Twitter: @dpyrooz This project was supported by Grant No. 2014-MU-CX-0111 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice, and was made possible with the assistance of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Justice or the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Understanding prison gangs SCHEDULE1. The problem of prison gangs 2. The LoneStar Project 3. Characteristics of prison gangs/gang members 4. Power and control on the inside 5. Q & A Responding to gangs 1. Joining/leaving in prison 2. Criminal and gang recidivism 3. Renouncement and disassociation 4. Policy/program implications 5. Q & A The LoneStar Project The problem of prison gangs 25% Winterdyk & Ruddell (2010) 19% N=37 20% NGIC (2011) Pyrooz & Mitchell 15% N=N/A (2018) 15% N=38 Hill 15% Wells et al. (2009) (2002) 12%, N=38 10% N=39 10% Camp & Camp (1985) 3% N=23 5% % of Prison Population, Gang Affiliated Gang Population, ofPrison % 0% 1984 2002 2008 2009 2011 2016 SOME INCONCLUSIVE “FACTS” • Misconduct, particularly violence • Orchestration -

Security Threat Groups "On the Inside"

SSecurityecurity TThreathreat GGrourouppss OONN TTHHEE IINNSSIIDDEE Texas Department of Criminal Justice The following are frequently asked questions and answers regarding Security Threat Groups (prison gangs), which should assist in giving some insight to an offender’s family and friends about the dangers of getting involved with a Security Threat Group while incarcerated in TDCJ-CID. What is a Security Threat Group (STG)? Any group of offenders TDCJ reasonably believes poses a threat to the physical safety of other offenders and staff due to the very nature of said Security Threat Group. TDCJ recognizes 12 Security Threat Groups: 1. Aryan Brotherhood of Texas 2. Aryan Circle 3. Barrio Azteca 4. Bloods 5. Crips 6. Hermanos De Pistoleros Latinos 7. Mexican Mafia 8. Partido Revolucionario Mexicanos 9. Raza Unida 10. Texas Chicano Brotherhood 11. Texas Mafia 12. Texas Syndicate Why does an offender join an STG? Some offenders join an STG in an effort to exert influence and take advantage of other offenders. They use any means necessary in an attempt to control their environment regardless of who gets hurt. Offenders may believe they need to join a gang for protection, but this is an inaccurate belief. By joining a gang, they put themselves in more danger because the rivals of their fellow gang members have also become their enemies. What are indicators of STG membership? Although STG members strive to keep all of their activities secret, including not informing family and friends of their ties to the gangs, many STG members put on specific gang tattoos and use hand signs. They also use terminology specific to their respective gangs in correspondence and often utilize friends and family members to forward gang-related information. -

The Dictionary Legend

THE DICTIONARY The following list is a compilation of words and phrases that have been taken from a variety of sources that are utilized in the research and following of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups. The information that is contained here is the most accurate and current that is presently available. If you are a recipient of this book, you are asked to review it and comment on its usefulness. If you have something that you feel should be included, please submit it so it may be added to future updates. Please note: the information here is to be used as an aid in the interpretation of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups communication. Words and meanings change constantly. Compiled by the Woodman State Jail, Security Threat Group Office, and from information obtained from, but not limited to, the following: a) Texas Attorney General conference, October 1999 and 2003 b) Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Security Threat Group Officers c) California Department of Corrections d) Sacramento Intelligence Unit LEGEND: BOLD TYPE: Term or Phrase being used (Parenthesis): Used to show the possible origin of the term Meaning: Possible interpretation of the term PLEASE USE EXTREME CARE AND CAUTION IN THE DISPLAY AND USE OF THIS BOOK. DO NOT LEAVE IT WHERE IT CAN BE LOCATED, ACCESSED OR UTILIZED BY ANY UNAUTHORIZED PERSON. Revised: 25 August 2004 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A: Pages 3-9 O: Pages 100-104 B: Pages 10-22 P: Pages 104-114 C: Pages 22-40 Q: Pages 114-115 D: Pages 40-46 R: Pages 115-122 E: Pages 46-51 S: Pages 122-136 F: Pages 51-58 T: Pages 136-146 G: Pages 58-64 U: Pages 146-148 H: Pages 64-70 V: Pages 148-150 I: Pages 70-73 W: Pages 150-155 J: Pages 73-76 X: Page 155 K: Pages 76-80 Y: Pages 155-156 L: Pages 80-87 Z: Page 157 M: Pages 87-96 #s: Pages 157-168 N: Pages 96-100 COMMENTS: When this “Dictionary” was first started, it was done primarily as an aid for the Security Threat Group Officers in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). -

Ac Gang Jordan Indictment

Case 6:17-cr-00327-DDD-CBW Document 1 Filed 12/14/17 Page 1 of 12 PagelD #: 1 DEC 112017 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA LAFAYETTE DIVISION UNDEE SEAL UNITED STATES OF AMERICA * CRIMINAL NO. & |"| t£ OO^Zl ~0\ VERSUS * 18 U.S.C. § 1959(a)(1) * 18 U.S.C. § 924®(1) JEREMY WADE JORDAN * District Judge [^)\^ a/k/a "JJ" * Magistrate Judge ^1 INDICTMENT THE GRAND JURY CHARGES: General Allegations The Racketeering Enterprise: The Aryan Circle Introduction 1. At all times relevant to this Indictment, the defendant JEREMY WADE JORDAN, a/k/a "JJ," and others, known and unknown, were members of the Aryan Circle (hereinafter the "AC"), a criminal organization whose members and associates engaged in narcotics distribution, firearms trafficking, and acts of violence involving murder, attempted murder, assault, robbery, witness intimidation, and kidnapping. At all times relevant to this Indictment, the AC operated throughout, Texas, Missouri, Oklahoma, Indiana, and Louisiana, including the Western District of Louisiana, and elsewhere. i Case 6:17-cr-00327-DDD-CBW Document 1 Filed 12/14/17 Page 2 of 12 PagelD #: 2 2. The AC, including its leaders, members, prospects, and associates, constituted an "enterprise," as defined in Title 18, United States Code, Section 1959(b)(2) (hereafter "the enterprise"), that is, a group of individuals associated in fact that engaged in and the activities of which affected interstate and foreign commerce. The enterprise constituted an ongoing organization whose members functioned as a continuing unit for a common purpose of achieving the objectives of the enterprise. -

Gang Threat Assesment

Texas Gang Threat Assessment A State Intelligence Estimate Produced by the Texas Joint Crime Information Center Intelligence & Counterterrorism Division Texas Department of Public Safety In collaboration with federal, state, and local law enforcement and criminal justice agencies August 2015 1 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 Executive Summary The key analytic judgments of this assessment are: • Gangs continue to represent a significant public safety threat to Texas due to their propensity for violence and heightened level of criminal activity. Of the incarcerated gang members within Texas Department of Criminal Justice prisons, over 60 percent are serving a sentence for violent crimes, including robbery (24 percent), homicide (16 percent), and assault/terroristic threat (15 percent). We assess there are likely more than 100,000 gang members in Texas. • The Tier 1 gangs in Texas for 2015 are Tango Blast and Tango cliques (estimated 15,000 members), Texas Syndicate (estimated 3,400 members), Texas Mexican Mafia (estimated 4,700 members), Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) (estimated 800 members), and Latin Kings (estimated 2,100 members). These groups pose the greatest gang threat to Texas due to their relationships with Mexican cartels, high levels of transnational criminal activity, level of violence, and overall statewide presence. • Gangs in Texas remain active in both human smuggling and human trafficking operations. Gang members associated with human smuggling have direct relationships with alien smuggling organizations (ASOs) and Mexican cartels. These organizations were involved in and profited from the recent influx of illegal aliens crossing the border in the Rio Grande Valley in 2014. Gang members involved in human trafficking, including commercial sex trafficking and compelling prostitution of adults and minors, exploit their victims through force, fraud or coercion, including recruiting and grooming them with false promises of affection, employment, or a better life. -

Gangs and Organized Crime Groups

DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE JOURNAL OF FEDERAL LAW AND PRACTICE Volume 68 November 2020 Number 5 Acting Director Corey F. Ellis Editor-in-Chief Christian A. Fisanick Managing Editor E. Addison Gantt Associate Editors Gurbani Saini Philip Schneider Law Clerks Joshua Garlick Mary Harriet Moore United States The Department of Justice Journal of Department of Justice Federal Law and Practice is published by Executive Office for the Executive Office for United States United States Attorneys Attorneys Washington, DC 20530 Office of Legal Education Contributors’ opinions and 1620 Pendleton Street statements should not be Columbia, SC 29201 considered an endorsement by Cite as: EOUSA for any policy, 68 DOJ J. FED. L. & PRAC., no. 5, 2020. program, or service. Internet Address: The Department of Justice Journal https://www.justice.gov/usao/resources/ of Federal Law and Practice is journal-of-federal-law-and-practice published pursuant to 28 C.F.R. § 0.22(b). Page Intentionally Left Blank Gangs & Organized Crime In This Issue Introduction....................................................................................... 1 David Jaffe Are You Maximizing Ledgers and Other Business Records in Drug and Organized Crime Investigations? ............. 3 Melissa Corradetti Jail and Prison Communications in Gang Investigations ......... 9 Scott Hull Federally Prosecuting Juvenile Gang Members........................ 15 David Jaffe & Darcie McElwee Scams-R-Us Prosecuting West African Fraud: Challenges and Solutions ................................................................................... 31 Annette Williams, Conor Mulroe, & Peter Roman Gathering Gang Evidence Overseas ............................................ 47 Christopher J. Smith, Anthony Aminoff, & Kelly Pearson Exploiting Social Media in Gang Cases ....................................... 67 Mysti Degani A Guide to Using Cooperators in Criminal Cases...................... 81 Katy Risinger & Tim Storino Novel Legal Issues in Gang Prosecutions .................................. -

2018 Texas Gang Threat Assessment

UNCLASSIFIED Texas Gang Threat Assessment November 2018 TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK UNCLASSIFIED 1 UNCLASSIFIED Texas Gang Threat Assessment A State Intelligence Estimate Produced by the Texas Joint Crime Information Center Intelligence & Counterterrorism Division Texas Department of Public Safety In collaboration with federal, state, and local law enforcement and criminal justice agencies November 2018 UNCLASSIFIED 2 UNCLASSIFIED THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK UNCLASSIFIED 3 UNCLASSIFIED (U) Executive Summary (U) The key analytic judgments of this assessment are: • (U) Gangs are a significant threat to public safety in Texas. Texas gangs are responsible for high levels of violence throughout the state, such as murder, sex trafficking, armed robbery, and aggravated assault. Texas gangs are heavily involved in the trafficking of methamphetamine, heroin, cocaine, and marijuana, and will often work with each other regardless of race or ideology in order to profit from the trafficking of drugs. We assess there are more than 100,000 gang members in Texas at any given time based on available information and data from multiple sources. • (U) Gangs in Texas continue to work closely with the Mexican cartels. Gangs provide direct support to cartel drug and human smuggling operations into and throughout Texas and the nation. Cartels also utilize gang members to procure and move weapons and money to Mexico, and sometimes to commit violent crimes on both sides of the border. Given the entrenched connections between gangs and cartels for drug distribution, we are concerned about the role gangs could play in trafficking fentanyl and contributing to the national opioid epidemic. -

Youtube™ for the Criminal Justice Educator

YouTube™ for the Criminal Justice Educator Lt. Raymond E. Foster, LAPD (ret.) Version 1.0 YouTube™ for the Criminal Justice Educator Version 1.0 Lieutenant Raymond E. Foster, LAPD (ret.) 1 © High Priority Targeting, Inc Introduction 3 (The following titles are hyperlinked to the sections in this book) Active Shooter 4 Careers 6 Constitution 9 Corrections 10 Courts 15 Crime 18 Domestic Violence 26 Drugs 27 Forensic Science 36 Gangs 39 History 52 International 56 Investigations 66 Issues 83 Juvenile 85 Leadership 87 Organized Crime 88 Police 91 Serial Killers 107 Technology 115 Terrorism 116 2 © High Priority Targeting, Inc The concept of YouTube™ for the Criminal Justice Educator is to the provide instructors with dynamic access to supplemental material via video. Nearly 400 videos are categorized and descriptions provided. The videos are classified into twenty-one categories. The links are live from this document. There is some overlap between the categories. The category titles are linked from the Table of Contents. Thus, if you want to view films on Active Shooter, click on Active Shooter in the Table of Contents and you will be taken to that page. Versions The Web is a constantly changing place. On YouTube™, videos are added, deleted and the URL modified constantly. You can help keep this document viable. If you find a dead link, think a certain video should not be included, or have a video you would like to be included, or would like to be notified of updated versions, send an email to [email protected]. You can also check the website www.criminaljusticevideos.com for updates. -

ARYAN PRISON GANGS Report J

SPECIAL ISSUE IntelligencePUBLISHED BY THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER ROLL CALL VIDEO ON ARYAN PRISON GANGS Report j ENCLOSED INSIDEARYAN PRISONARYAN PRISON GANGS THE CONSPIRATORIAL IDEOLOGY BEHIND A DOUBLE COP-KILLER IS SPREADING RAPIDLY A VIOLENT GANGSMOVEMENT SPREADS FROM THE PRISONS TO THE STREETS PLUS ‘SOVEREIGN’PRISON LEADERSHIP BREAK TIPS FOR LAWTIMELINE ENFORCEMENT ‘SOVEREIGN’SMASHING THE DICTIONARY SHAMROCK 211 CrewProfiles Member of Implicatedtop activists in Killing A ChronologySovereign ofdanger Crime signsLinked to FederalDecoding Indictments the bizarre Expose of Colorado Prisons Chief White Supremacist Prison Gangs Aryan Brotherhood Violence special report I Intelligence Report INTELLIGENCE REPORT EDITOR Mark Potok INTELLIGENCE PROJECT DIRECTOR Heidi Beirich SENIOR WRITERS Ryan Lenz, Don Terry STAFF WRITER Evelyn Schlatter CHIEF INVESTIGATOR Joseph Roy Sr. SENIOR INTELLIGENCE ANALYST Laurie Wood INFORMATION MANAGER Michelle Bramblett RESEARCH ANALYSTS Anthony Griggs, Janet Smith PROGRAM ASSOCIATE Karla Griffin RESEARCHERS Angela Freeman, Karmetriya Jackson DIRECTOR OF CAMPAIGNS Josh Glasstetter DESIGN DIRECTOR Russell Estes DESIGNERS Shannon Anderson, Valerie Downes, Michelle Leland, Sunny Paulk, Scott Phillips, Kristina Turner PRODUCTION MANAGER Regina Collins SOCIAL MEDIA COORDINATOR Leanne Naramore 1 Smashing the Shamrock MEDIA AND GENERAL INQUIRIES Heidi Beirich Imprisoned leaders of the Aryan Brotherhood have long laughed off au- LAW ENFORCEMENT INQUIRIES Joseph Roy Sr. thorities’ attempts to prevent them from running