Chapter 9: Prison Subculture and Prison Gang Influence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18 CR 2 4 5 JED ) Plaintiff, ) FILED UNDER SEAL ) V

-" ... F LED DEC 7 2018 Mark L VI IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT U S D . t cCartt, Clerk . /STA/CT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF OKLAHOMA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) Case No. 18 CR 2 4 5 JED ) Plaintiff, ) FILED UNDER SEAL ) v. ) INDICTMENT ) [COUNT 1: 18 U.S.C. § 1962(d) CHRISTOPHER K. BALDWIN, ) Conspiracy to Participate in a a/k/a "Fat Bastard," ) Racketeering Enterprise; MATHEW D. ABREGO, ) COUNT 2: 21 U.S.C. §§ 846 and JEREMY C. ANDERSON, ) 84l(b)(l)(A)(viii) - Drug Conspiracy; a/k/a "JC," ) COUNT 3: 18 U.S.C. § 1959(a)(l)- DUSTIN T. BAKER, ) Kidnapping] MICHAELE. CLINTON, ) a/k/a "Mikey Clinton," ) EDDIE L. FUNKHOUSER, ) JOHNNY R. JAMESON, ) a/k/a "JJ," ) ELIZABETH D. LEWIS, ) a/k/a "Beth Lewis," ) CHARLES M. MCCULLEY, ) a/k/a "Mark McCulley," ) DILLON R. ROSE, ) RANDY L. SEATON, ) BRANDY M. SIMMONS, ) JAMES C. TAYLOR, a/k/a "JT," ) ROBERT W. ZEIDLER, ) a/k/a "Rob Z," ) BRANDON R. ZIMMERLEE, ) LISA J. LARA, ) SISNEY A. LARGE, ) RICHARD W. YOUNG, ) a/k/a "Richard Pearce," ) ) Defendants. ) .• THE GRAND JURY CHARGES: COUNT ONE [18 u.s.c. § 1962(d)] INTRODUCTION 1. At all times relevant to this Indictment, the defendants, CHRISTOPHER K. BALDWIN, a/k/a "Fat Bastard" ("Defendant BALDWIN"), MATHEW D. ABREGO ("Defendant ABREGO"), JEREMY C. ANDERSON, a/k/a "JC" ("Defendant ANDERSON"), DUSTIN T. BAKER ("Defendant BAKER"), MICHAEL E. CLINTON, a/k/a "Mikey Clinton" ("Defendant CLINTON"), EDDIE L. FUNKHOUSER ("Defendant FUNKHOUSER"), JOHNNY R. JAMESON, a/k/a "JJ" ("Defendant JAMESON"), ELIZABETH D. -

Southwest Border Gang Recognition

SOUTHWEST BORDER GANG RECOGNITION Sheriff Sigifredo Gonzalez, Jr. Zapata County, Texas Army National Guard Project April 30th, 2010 Southwest Border Gang Recognition – Page 1 of 19 Pages SOUTHWEST BORDER GANG RECOGNITION Lecture Outline I. Summary Page 1 II. Kidnappings Page 6 III. Gangs Page 8 IV. Overview Page 19 Southwest Border Gang Recognition – Page 2 of 19 Pages Summary The perpetual growth of gangs and active recruitment with the state of Texas, compounded by the continual influx of criminal illegal aliens crossing the Texas-Mexico border, threatens the security of all U.S. citizens. Furthermore, the established alliances between these prison and street gangs and various drug trafficking organizations pose a significant threat to the nation. Gangs now have access to a larger supply of narcotics, which will undoubtedly increase their influence over and presence in the drug trade, as well as increase the level of gang-related violence associated with illegal narcotics trafficking. Illegal alien smuggling has also become profitable for prison and other street gangs, and potentially may pose a major threat to national security. Multi-agency collaboration and networking—supplemented with modern technology, analytical resources, and gang intervention and prevention programs—will be critical in the ongoing efforts to curtail the violence associated with the numerous gangs now thriving in Texas and the nation.1 U.S.-based gang members are increasingly involved in cross-border criminal activities, particularly in areas of Texas and California along the U.S.—Mexico border. Much of this activity involves the trafficking of drugs and illegal aliens from Mexico into the United States and considerably adds to gang revenues. -

White Supremacist Prison Gangs in the United States a Preliminary Inventory Introduction

White Supremacist Prison Gangs in the United States A Preliminary Inventory Introduction With rising numbers and an increasing geographical spread, for some years white supremacist prison gangs have constitut- ed the fastest-growing segment of the white supremacist movement in the United States. While some other segments, such as neo-Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan, have suffered stagnation or even decline, white supremacist prison gangs have steadily been growing in numbers and reach, accompanied by a related rise in crime and violence. What is more, though they are called “prison gangs,” gangs like the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas, Aryan Circle, European Kindred and others, are just as active on the streets of America as they are behind bars. They plague not simply other inmates, but also local communities across the United States, from California to New Hampshire, Washington to Florida. For example, between 2000 and 2015, one single white supremacist prison gang, the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas, was responsible for at least 33 murders in communities across Texas. Behind these killings were a variety of motivations, including traditional criminal motives, gang-related murders, internal killings of suspected informants or rules-breakers, and hate-related motives directed against minorities. These murders didn’t take place behind bars—they occurred in the streets, homes and businesses of cities and towns across the Lone Star State. When people hear the term “prison gang,” they often assume that such gang members plague only other prisoners, or perhaps also corrections personnel. They certainly do represent a threat to inmates, many of whom have fallen prey to their violent attacks. -

H I S T O R Y I S a W E a P O N ! BLACK AUGUST RESISTANCE August, One of the Hottest Months of the Year, Is Upo'n Us Again

HISTORY IS A WEAPON! BLACK AUGUST RESISTANCE August, one of the hottest months of the year, is upo'n us again. For many of us in the "New Afrikan Independence Movement", August is a month of both great historical and spiritual significance. It is one of the hottest months in many ways, many of the great Afrrkan slave rebellions, including Gabriel Prosser's and Nat Turner's were planned for August. It is the month of the birth of the great Pan-Afri- kanist and Black Nationalist leaders, Marcus Garvey and also of our New Afrikan Freedom Fighter, Dr. Mutulu Shakur. New Afrikans took to the streets in rebellions in Watts, California in August 1965. On August 18,1971 in Jackson Mississippi, the offical residence of the Republic Of New Afrika was raided by Mississippi police and F.B.I, agents, gunfire was exchanged and when the smoke had cleared, one policeman laid dead and two other agents were wounded. For success- fully defending themselve's, these brothers and sisters were charged with "waging war against the state of Mississippi", they became known as the RNA-J5/. August 1994. marks the 15th anniversary of Black August commemorations, the promotion of a couscious, "non-sectarian mass based". Mew Afrikan Resistance Culture, both inside and outside the prison walls all across the U.S. Empire. Black August originally started among the brothers in the California penal system to honor three fallen comrades and to promote culture resistance and revolutionary developement. The first brother, Jonathan Jackson, a 17 year old manchild was gunned down August 7,1970 outside a Marin County California courthouse in an armed attempt to liberate three imprisoned Black Liberation Fighters (James Me Clain, William Christmans, and Ruchell Magee). -

Download Kentucky Indictment

Case: 7:20-cr-00017-REW-EBA Doc #: 1 Filed: 09/03/20 Page: 1 of 13 - Page ID#: 1 Eastern D!Jtrict of Kentucky FILED UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF KENTUCKY SEP O3 2020 SOUTHERN DIVISION AT LEXINGTON PIKEVILLE ROBERT R. CARR CLERK U.S. DISTRICT COURT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. INDICTMENT NO. 7:z.5-02.-lJ-(<'i)AJ MITCHELL FARKAS, UNDER SEAL aka LIFTER, JONATHAN GOBER, aka TUCKER, JAMES POOLE, aka REDWOOD, and ANDREW TINLIN, aka TIN * * * * * THE GRAND JURY CHARGES: GENERAL ALLEGATIONS Indictment 1. At all times relevant to this Indictment, the defendants, MITCHELL FARKAS, aka LIFTER, JONATHAN GOBER, aka TUCKER, JAMES POOLE, aka REDWOOD, ANDREW TINLIN, aka TIN, and others, known and unknown, were members of the Aryan Circle (hereinafter the "AC"), a criminal organization whose members and associates engaged in narcotics distribution, firearms trafficking, and acts of violence including acts involving murder, assault, robbery, witness intimidation, and kidnapping. At all times relevant to this Indictment, the AC operated throughout Kentucky, Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, Indiana, New Jersey, and Arizona, 1 Case: 7:20-cr-00017-REW-EBA Doc #: 1 Filed: 09/03/20 Page: 2 of 13 - Page ID#: 2 including in the Eastern District of Kentucky, and elsewhere. Structure and Operation of the Enterprise 2. The structure and operation of the AC included, but was not limited to, the following: a. The AC was a violent, race-based, "whites only" prison-based gang with hundreds of members operating inside and outside of state and federal penal institutions throughout Kentucky, Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, Indiana, New Jersey, and Arizona. -

Remarks of the Attorney General Before the President's Commission on Organized Crime Washington, D

REMARKS OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL BEFORE THE PRESIDENT'S COMMISSION ON ORGANIZED CRIME WASHINGTON, D. C. NOVEMBER 29, 1983 Thank you, Judge Kaufman and members of the commission. I am pleased to be here this morning as the President's Commission on Organized Crime formally undertakes its important mission. Organized crime is a subject that affects all of us every day but generally is hidden from public view. It causes our taxes to go up, it adds to the cost of what we buy, and, worst of all, it threatens our personal safety and that of our families indeed our very freedom. Organized crime is an insidious cancer on our society, and it is clearly a principal law enforcement responsibility of the federal government to attack organized crime with the best weapons we can fashion. Today I would like to begin by providing some context for this commission's work by reviewing the history of organized crime and the government's response to it. Organized crime in America started out as a local enterprise. During the Nineteenth Century and until Prohibition, a gang worked a city, often just a neighborhood. There was no national connection and thus no nationally dominant group. With the advent of Prohibition, organized crime became a national enterprise as it sought to market and distribute liquor throughout the country. Strife among gangs abated as cooperation became necessary in the effort to control larger markets. A national criminal federation emerged. Meeting in New York in 1934, the nation's most powerful gangsters 'lent support to the idea of a national crime organization and acknowledged the territorial claims of 24 crime families in cities across the nation. -

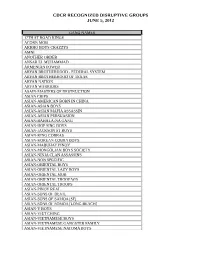

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

HISTORY of STREET GANGS in the UNITED STATES By: James C

Bureau of Justice Assistance U.S. Department of Justice NATIO N AL GA ng CE N TER BULLETI N No. 4 May 2010 HISTORY OF STREET GANGS IN THE UNITED STATES By: James C. Howell and John P. Moore Introduction The first active gangs in Western civilization were reported characteristics of gangs in their respective regions. by Pike (1873, pp. 276–277), a widely respected chronicler Therefore, an understanding of regional influences of British crime. He documented the existence of gangs of should help illuminate key features of gangs that operate highway robbers in England during the 17th century, and in these particular areas of the United States. he speculates that similar gangs might well have existed in our mother country much earlier, perhaps as early as Gang emergence in the Northeast and Midwest was the 14th or even the 12th century. But it does not appear fueled by immigration and poverty, first by two waves that these gangs had the features of modern-day, serious of poor, largely white families from Europe. Seeking a street gangs.1 More structured gangs did not appear better life, the early immigrant groups mainly settled in until the early 1600s, when London was “terrorized by a urban areas and formed communities to join each other series of organized gangs calling themselves the Mims, in the economic struggle. Unfortunately, they had few Hectors, Bugles, Dead Boys … who found amusement in marketable skills. Difficulties in finding work and a place breaking windows, [and] demolishing taverns, [and they] to live and adjusting to urban life were equally common also fought pitched battles among themselves dressed among the European immigrants. -

Mississippi Analysis and Information Center Gang Threat Assessment 2010

Mississippi Analysis and Information Center Gang Threat Assessment 2010 This information should be considered LAW ENFORCEMENT SENSITIVE. Further distribution of this document is restricted to law enforcement and intelligence agencies only, unless prior approval from the Mississippi Analysis and Information Center is obtained. NO REPORT OR SEGMENT THEREOF MAY BE RELEASED TO ANY MEDIA SOURCES. It contains information that may be exempt from public release under the Freedom of Information Act (5 USC 552). Any request for disclosure of this document or the information contained herein should be referred to the Mississippi Analysis & Information Center: (601) 933-7200 or [email protected] MSAIC 2010 GANG THREAT ASSESSMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Purpose ................................................................................................. 2 Executive Summary ............................................................................ 2 Key Findings ........................................................................................ 3 Folk Nation .......................................................................................... 7 Gangster Disciples ........................................................................... 9 Social Network Presence .......................................................... 10 Simon City Royals ......................................................................... 10 Social Network Presence .......................................................... 11 People Nation .................................................................................... -

What Have We Learned About Prison Gangs? Findings from the Lonestar Project

What have we learned about prison gangs? Findings from the LoneStar Project David C. Pyrooz, Ph.D. Department of Sociology Institute of Behavioral Science University of Colorado Boulder A Presentation to the UTEP Center for Law & Human Behavior Email: [email protected] Phone: (303) 492-3241 The LoneStar Project Twitter: @dpyrooz This project was supported by Grant No. 2014-MU-CX-0111 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice, and was made possible with the assistance of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Justice or the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Understanding prison gangs SCHEDULE1. The problem of prison gangs 2. The LoneStar Project 3. Characteristics of prison gangs/gang members 4. Power and control on the inside 5. Q & A Responding to gangs 1. Joining/leaving in prison 2. Criminal and gang recidivism 3. Renouncement and disassociation 4. Policy/program implications 5. Q & A The LoneStar Project The problem of prison gangs 25% Winterdyk & Ruddell (2010) 19% N=37 20% NGIC (2011) Pyrooz & Mitchell 15% N=N/A (2018) 15% N=38 Hill 15% Wells et al. (2009) (2002) 12%, N=38 10% N=39 10% Camp & Camp (1985) 3% N=23 5% % of Prison Population, Gang Affiliated Gang Population, ofPrison % 0% 1984 2002 2008 2009 2011 2016 SOME INCONCLUSIVE “FACTS” • Misconduct, particularly violence • Orchestration -

The Criminal Organization

Osgoode Hall Law School of York University Osgoode Digital Commons Organized Crime in North America and the World: Complete Bibliography A Bibliography September 2017 Part 4: The rC iminal Organization Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/bibliography Recommended Citation "Part 4: The rC iminal Organization" (2017). Complete Bibliography. 5. http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/bibliography/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Organized Crime in North America and the World: A Bibliography at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Complete Bibliography by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. Part Four: The Criminal Organization This part of the bibliography provides references to literature that describes and/or examines the criminal organization in depth. Particular emphasis is placed on works that explore salient issues relating to the organization of crime, such as group structure, membership, recruitment, codes, etc. Adams, James. 1991. “Medellin Cartel.” American Spectator. 24: December: 22-5. Albini, J. L. 1975.”Mafia As Method: A Comparison Between Great Britain and U.S.A. Regarding the Existence and Structure of Types of Organized Crime.” International Journal of Criminology and Penology. 3: 295-305. Bossard, Andre. 1998. “Mafias, Triads, Yakuza and Cartels: A Comparative Study of Organized Crime.” Crime and Justice International. 14(December): 5-32. Chu, Yiu Kong. 2000. The Triads As Business. Routledge Studies in Modern History of Asia, 6. Routledge. Coleman, James W. 1982. “The Business of Organized Crime: A Cosa Nostra Family.” American Journal of Sociology. 88(1, July): 235. Coles, Nigel. -

U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Washington, D.C. 20535 August 24, 2020 MR. JOHN GREENEWALD JR. SUITE

U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Washington, D.C. 20535 August 24, 2020 MR. JOHN GREENEWALD JR. SUITE 1203 27305 WEST LIVE OAK ROAD CASTAIC, CA 91384-4520 FOIPA Request No.: 1374338-000 Subject: List of FBI Pre-Processed Files/Database Dear Mr. Greenewald: This is in response to your Freedom of Information/Privacy Acts (FOIPA) request. The FBI has completed its search for records responsive to your request. Please see the paragraphs below for relevant information specific to your request as well as the enclosed FBI FOIPA Addendum for standard responses applicable to all requests. Material consisting of 192 pages has been reviewed pursuant to Title 5, U.S. Code § 552/552a, and this material is being released to you in its entirety with no excisions of information. Please refer to the enclosed FBI FOIPA Addendum for additional standard responses applicable to your request. “Part 1” of the Addendum includes standard responses that apply to all requests. “Part 2” includes additional standard responses that apply to all requests for records about yourself or any third party individuals. “Part 3” includes general information about FBI records that you may find useful. Also enclosed is our Explanation of Exemptions. For questions regarding our determinations, visit the www.fbi.gov/foia website under “Contact Us.” The FOIPA Request number listed above has been assigned to your request. Please use this number in all correspondence concerning your request. If you are not satisfied with the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s determination in response to this request, you may administratively appeal by writing to the Director, Office of Information Policy (OIP), United States Department of Justice, 441 G Street, NW, 6th Floor, Washington, D.C.