Kennisis Watershed & Lakes Management Plan September 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revised Water Quality Model and Lake System Health Program

Hutchinson Environmental Sciences Ltd. Revised Water Quality Model and Lake System Health Program Prepared for: District Municipality of Muskoka Job #: J150074 April 2016 Final Report Hutchinson Environmental Sciences Ltd. J150074 , District Municipality of Muskoka Revised Water Quality Model and Lake System Health Program April 5, 2016 HESL Job #: J150074 Ms. Christy Doyle Director of Watershed Programs District Municipality of Muskoka 70 Pine St. Bracebridge ON P1L 1N3 Dear Ms. Doyle: Re: Revised Water Quality Model and Lake System Health Program – Final Report We are pleased to submit this final report of the Revised Water Quality Model and Lake System Health Program for the District Municipality for Muskoka lakes. This has been a most challenging and scientifically interesting project, and we thank The District of Muskoka for their continued support over the course of the last several years while we worked to develop recommendations to revise the program to reflect the results of review in 2013, and again in 2015 to change the program emphasis. We appreciate that there may still be discussions required to move the technical recommendations presented herein into planning policy and look forward to the opportunity to assist with that. Sincerely, per: Hutchinson Environmental Sciences Ltd. Neil J. Hutchinson, Ph.D. President [email protected] Hutchinson Environmental Sciences Ltd. J150074 , District Municipality of Muskoka Revised Water Quality Model and Lake System Health Program Signatures Dörte Köster, Ph.D. -

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Lakes with an Asterisk * Do Not Have Depth Information and Appear with Improvised Contour Lines County Information Is for Reference Only

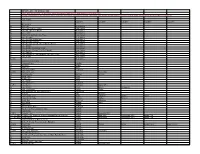

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Lakes with an asterisk * do not have depth information and appear with improvised contour lines County information is for reference only. Your lake will not be split up by county. The whole lake will be shown unless specified next to name eg (Northern Section) (Near Follette) etc. LAKE NAME COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY Great Lakes GL Lake Erie Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Port of Toledo) Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Western Basin) Great Lakes GL Lake Huron Great Lakes GL Lake Huron (w West Lake Erie) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (Northeast) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (South) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (w Lake Erie and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Rochester Area) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Stoney Pt to Wolf Island) Great Lakes GL Lake Superior Great Lakes GL Lake Superior (w Lake Michigan and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake St Clair Great Lakes GL (MI) Great Lakes Cedar Creek Reservoir AL Deerwood Lake Franklin AL Dog River Shelby AL Gantt Lake Mobile AL Goat Rock Lake * Covington AL (GA) Guntersville Lake Lee Harris (GA) AL Highland Lake * Marshall Jackson AL Inland Lake * Blount AL Jordan Lake Blount AL Lake Gantt * Elmore AL Lake Jackson * Covington AL (FL) Lake Martin Covington Walton (FL) AL Lake Mitchell Coosa Elmore Tallapoosa AL Lake Tuscaloosa Chilton Coosa AL Lake Wedowee (RL Harris Reservoir) Tuscaloosa AL Lay Lake Clay Randolph AL Lewis Smith Lake * Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Logan Martin Lake Cullman Walker Winston AL Mobile Bay Saint Clair Talladega AL Ono Island Baldwin Mobile AL Open Pond * Baldwin AL Orange Beach East Covington AL Bon Secour River and Oyster Bay Baldwin AL Perdido Bay Baldwin AL (FL) Pickwick Lake Baldwin Escambia (FL) AL (TN) (MS) Pickwick Lake (Northern Section, Pickwick Dam to Waterloo) Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL (TN) (MS) Shelby Lakes Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL Tallapoosa River at Fort Toulouse * Baldwin AL Walter F. -

(COMMERCIAL LIST) BETWEEN: 1711423 ONTARIO LIMITED Ap

Court File No. CV-20-00637615-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE (COMMERCIAL LIST) B E T W E E N: 1711423 ONTARIO LIMITED Applicant and OLD MILL MARINA (KAWAGAMA) LIMITED Respondent APPLICATION UNDER Section 243(1) of the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. B-3, and Section 101 of the Courts of Justice Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. C.43 FIRST REPORT TO THE COURT OF MNP LTD IN ITS CAPACITY AS RECEIVER AND MANAGER OF THE ASSETS, UNDERTAKINGS, AND PROPERTIES OF OLD MILL MARINA (KAWAGAMA) LIMITED September 22, 2020 Page 1 of 18 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 3 PURPOSE OF THIS REPORT ................................................................................................... 5 DISCLAIMER AND TERMS OF REFERENCE ..................................................................... 5 RECEIVER’S ACTIVITIES ....................................................................................................... 6 SALE PROCESS ........................................................................................................................... 8 SALE AGREEMENT RECOMMENDATIONS……………………………………………..12 CONFIDENTIAL APPENDICES ............................................................................................. 13 STATEMENT OF RECEIPTS AND DISBURSEMENTS ..................................................... 14 PROFESSIONAL FEES ........................................................................................................... -

District of Muskoka Recreational Water Quality Model Review

DISTRICT OF MUSKOKA RECREATIONAL WATER QUALITY MODEL REVIEW TOWNSHIP OF MUSKOKA LAKES JUNE 16, 2016 RECREATIONAL WATER QUALITY MODEL REVIEW PRESENTATION FLOW • INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXT • MODEL REVIEW: KEY FINDINGS • PLANNING IMPLICATIONS • NEXT STEPS • DISCUSSION AND QUESTIONS THE PROJECT: RECREATIONAL WATER QUALITY MODEL REVIEW KEY FINDINGS 1. MODEL IS NOT SUPPORTED ON AN INDIVIDUAL LAKE BASIS 2. ALL LAKES WARRANT PROTECTION, WITH MULTIPLE STRESSORS CONSIDERED 3. MOVE TOWARD RELIANCE ON MEASURED CHANGES AND OBSERVED WATER QUALITY - PHOSPHORUS IS STILL A GOOD INDICATOR 4. SEVEN “TRANSITIONAL” LAKES WARRANT ADDITIONAL STUDY “Phosphorus is the window into our lakes” RECREATIONAL WATER QUALITY MODEL REVIEW PLANNING IMPLICATIONS 5 MUSKOKA WATER QUALITY POLICIES Lake Classification Policy Requirement Implementation Over Threshold Lot Level Study High Sensitivity Lot Level Study SITE PLAN Moderate Sensitivity Site Plan Required Approach Current Policy Low Sensitivity Site Plan Recommended BMPs Standard Categories Implementation Vegetated Buffers X Shoreline Naturalization X Standard Protection Site Plan Required Soil Protection X On‐Site Stormwater Control X Transitional Lakes (7) Enhanced Protection Limit Impervious Surfaces X Enhanced Septic Setback (30m) X Lake Level Study Enhanced Lot Size X Direction Securities and Compliance Monitoring X • Simplified and consistent Proposed Policy • Leading-edge and defensible • Based on observable indicators • 20% of lakes impacted INTERIM COMMENTING • EXISTING POLICIES ARE OPEN TO CHALLENGE • ALSO CHALLENGES -

Background Report

Background Report TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..............................................................................................................................................5 Our Supporters .......................................................................................................................................................5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................6 INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................................................................9 Past Indicators ........................................................................................................................................................9 Muskoka’s Watersheds ....................................................................................................................................... 11 Subwatershed Evaluation .................................................................................................................................... 14 Benchmarks ......................................................................................................................................................... 16 Value of Ecosystems ............................................................................................................................................ 17 LAND ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Great Lakes Lake Erie

4389 # of lakes LAKE NAME COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY 99000 GL Great Lakes Great Lakes 99005 GL Lake Erie Great Lakes 99010 GL Lake Erie (Lake Erie Islands Region) Great Lakes 99015 GL Lake Erie (Port of Toledo Region) Great Lakes 99020 GL Lake Erie (Put-In-Bay Area) Great Lakes 99025 GL Lake Erie (Western Basin Region) Great Lakes 99030 GL Lake Huron Great Lakes 99035 GL Lake Huron (With Lake Erie - Western Section) Great Lakes 99040 GL Lake Michigan (Northeastern Section) Great Lakes 99045 GL Lake Michigan (Southern Section) Great Lakes 99050 GL Lake Michigan (With Lake Erie and Lake Huron) Great Lakes 99055 GL Lake Michigan (Lighthouses and Shipwrecks) Great Lakes 99060 GL Lake Ontario Great Lakes 99065 GL Lake Ontario (Rochester Area) Great Lakes 99066 GL Lake Ontario (Stoney Pt to Wolf Island) Great Lakes 99070 GL Lake Superior Great Lakes 99075 GL Lake Superior (With Lake Michigan and Lake Huron) Great Lakes 99080 GL Lake Superior (Lighthouses and Shipwrecks) Great Lakes 10000 AL Baldwin County Coast Baldwin 10005 AL Cedar Creek Reservoir Franklin 10010 AL Dog River * Mobile 10015 AL Goat Rock Lake * ChaMbers Lee Harris (GA) Troup (GA) 10020 AL Guntersville Lake Marshall Jackson 10025 AL Highland Lake * Blount 10030 AL Inland Lake * Blount 10035 AL Lake Gantt * Covington 10040 AL Lake Jackson * Covington Walton (FL) 10045 AL Lake Jordan ElMore Coosa Chilton 10050 AL Lake Martin Coosa ElMore Tallapoosa 10055 AL Lake Mitchell Chilton Coosa 10060 AL Lake Tuscaloosa Tuscaloosa 10065 AL Lake Wedowee Clay Cleburne Randolph 10070 AL Lay -

Final Phase 1 Report of the Master Plan of Archaeological Resources of the District Municipality of Muskoka

FINAL PHASE 1 REPORT OF THE MASTER PLAN OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESOURCES OF THE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY OF MUSKOKA Edited by D.A Robertson and R.E Williamson ARCHAEOLOGICAL SERVICES INC. Submitted to THE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY OF MUSKOKA and THE MOHAWKS OF GmSON ARCHAEOLOGICAL SERVICES INC. 662 Bathurst St. Toronto, Ontario MSS 2R3 in association with . Unterman McPhail Cuming Associates Mount McGovern Co., Ltd. Dr. Carole Carpenter Ms. Susan Maltby, Conservator July, 1992 Project Personnel Project Director: Dr. Ronald F. Williamson l Project Researchers: Dr. Carole H. CarpenterS Mr. Martin S. Cooperl Mr. David Cuming2 Ms. Eva M. MacDonald1 Mr. Robert 1. MacDonaldl Ms. Barbara McPhail2 Ms. Susan L. Maltby4 Mr. David A Robertson1 Ms. Jean Simonten2 Mr. Phillip J. Wright 3 Project Information and Communication Co-Ordinators: Ms. Beverly J. Gamerl Ms. Eva M. MacDonald1 lArchaeological Services Inc. 2Untennan McPhail Cuming Associates 3Mount McGovern Co. Ltd. 4Susan L. Maltby, Conservator sYork University " ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many individuals have contributed to the collection and compilation of data for this study. It is only through their co-operation and generosity that this work was made possible. We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Mr. Ron Reid, of the Muskoka Heritage Areas Program, for providing detailed environmental data which has been generated as part of the Heritage Areas study; Ms. Judi Brouse, of the District of Muskoka, for her support and provision of mapping; Ms. Bernice Field, of the Ministry of Culture and Communications, for providing access to the database of archaeological sites listed with that Ministry; Mr. Peter Carruthers, of the Ministry of Culture and Communications, for information regarding the survey of the Severn waterway; and Dr. -

Inland Ontario Lakes Designated for Lake Trout Management

Inland Ontario Lakes Designated for Lake Trout Management July 2015 . ISBN 978-1-4606-6257-1 (PDF) Fisheries Section Species Conservation Policy Branch Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry P.O. Box 7000, 300 Water Street Peterborough, ON K9J 8M5 “A prerequisite to the effective management of a resource is a knowledge of the distribution and magnitude of that resource.” Introductory sentence from “The Distribution and Characteristics of Ontario Lake Trout Lakes” (Martin and Olver 1976). ii Abstract Lake Trout lakes are rare. Only about one percent of Ontario’s lakes contain Lake Trout, but this represents 20-25% of all Lake Trout lakes in the world. The province, therefore, has a great responsibility to manage them wisely. OMNRF efforts to develop a coordinated strategy to protect Lake Trout populations in Ontario requires a comprehensive list of lakes currently designated for Lake Trout management. This report lists the inland Ontario lakes (exclusive of the Great Lakes) that are currently designated for Lake Trout management. In addition, the list classifies the lakes as to whether they are to be managed for naturally reproducing populations (‘Natural’ lakes) or as put-grow-take (‘P-G-T’) lakes. ‘Natural’ lakes include those lakes that may have lost populations but have been identified for rehabilitation. ‘P-G-T’ lakes are managed to provide recreational fishing opportunities and/or to direct angling effort away from more sensitive ‘Natural’ lakes. OMNRF policies or guidelines may be applied differently depending on the lake classification, or in other cases may be applied to both classifications in a similar manner. -

Municipal Cultural Plan

MUNICIPAL CULTURAL PLAN May 16, 2013 Prepared by: Planscape Inc. 104 Kimberley Avenue Bracebridge, ON P1L 1Z8 The Township of Algonquin Highlands Municipal Cultural Plan Funding Provided by: Ontario Ministry of Tourism and Culture The Township of Algonquin Highlands Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Cultural Planning ........................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Purpose of a Municipal Cultural Plan ........................................................................... 1 1.3 Development of the Plan: Study Objectives and Work Program ................................... 2 1.4 Steering Committee ..................................................................................................... 3 2.0 BACKGROUND RESEARCH ......................................................................................... 4 3.0 CULTURAL PROFILE .................................................................................................... 5 3.1 Community Profile........................................................................................................ 5 3.2 Community Trends ......................................................................................................11 4.0 PLANNING CONTEXT ...................................................................................................11 4.1 Provincial Policy Direction ...........................................................................................12 -

Muskoka Watershed Report Card BACKGROUND 2018 Muskoka Watershed Report Card Background Report

July 2018 Muskoka REPORT Watershed www.muskokawatershed.org Muskoka Watershed Report Card Council BACKGROUND 2018 Muskoka Watershed Report Card Background Report Table of Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Muskoka Watershed Council ................................................................................................................... 5 The District Municipality of Muskoka ....................................................................................................... 5 Key Scientific Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 5 Contributors ................................................................................................................................................ 6 Data Sources .............................................................................................................................................. 6 Letter from the Chair .................................................................................................................................... -

REPORT of the MASTER PLAN of ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESOURCES ( of the Districf MUNICIPALITY of MUSKOKA and the WAHTA MOHAWKS

REPORT OF THE MASTER PLAN OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESOURCES ( OF THE DISTRICf MUNICIPALITY OF MUSKOKA AND THE WAHTA MOHAWKS VOLUME 1 BACKGROUND RESEARCH ~...",.,.--_ ... .. .,~".~-"'''--- '- ( scale o 20 em ope Petroglyph Site (BeGu-4) Submitted to THE DISTRICf MUNICIPALITY OF MUSKOKA and THE WAHTA MOHAWKS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SERVICES INC. February 1994 REPORT OF THE MASTER PLAN OF HERITAGE RESOURCES OF THE DISTRICf MUNICIPALITY OF MUSKOKA AND THE WAHTA MOHAWKS VOLUME 1 BACKGROUND RESEARCH Submitted to THE DISTRICf MUNICIPALITY OF MUSKOKA and THE WAHTA MOHAWKS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SERVICES INC. 662 Bathurst St Toronto, Ontario M5S 2R3 in association with Unterman McPhail Cuming Associates Mount McGovern Co., Ltd. Dr. Carole Carpenter Ms. Susan L. Maltby, Conservator February, 1994 Project Personnel Project Director: Dr. Ronald F. Williamson' Research and Report Preparation: Dr. Carole H. Carpenter" Mr. Martin S. Cooper' Mr. David Cuming" Ms. Eva M. MacDonald1 Mr. Robert 1 MacDonald1 Ms. Barbara McPhail 2 Ms. Susan L Maltby" Mr. David A Robertson! Ms. Jean Simonton" Mr. Phillip J. Wright3 Report Editors: Mr. David A Robertson Dr. Ronald F. Williamson Project Information and Communication Co-Ordinators: Ms. Beverly J. Gamer' Ms. Eva M. Maclsonald! lArchaeological Services Inc. 2Unterman McPhail CumingAssociates 3Mount McGovern Co. Ltd. "Susan L. Maltby, Conservator sYork University ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many individuals have contnbuted to the collection and compilation of data for this study. It is only through their co-operation and generosity that this work was made possible. We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Mr. Ron Reid, of the Muskoka Heritage Areas Program, for providing detailed environmental data which has been generated as part ofthe Heritage Areas study; Ms. -

The Cottages on Main Street Dorset, Ontario

The Cottages On Main Street Dorset, Ontario Compiled and edited by Paul Dillenberger The Cottages on Main Street Dorset, Ontario INTRODUCTION Heading south, the road that passes by the Dorset Community Center and Robinsonǯs General Store, goes over the old bridge, ǡDz ǡdz a DzǤdz It is also known as Rte. 39. It used to be the only road that went through Dorset (before the Hwy. 35 bypass). At that time, Main Street consisted of the end of Hwy. 118 (renamed Hwy. 117) and part of the Bobcaygeon Road (later the old Hwy. 35). At the southern most part of Main Street (past the Dorset Garage), is a string of cottages along the shore of Trading Bay just outside the village of Dorset. Many of those cottages, due to their pro Dzdz ǡ cottages on Lake of Bays. This booklet is about those cottages. First you will be introduced to the history of the village of Dorset, many of whose businesses operated on Main Street. Then four cottages on Main Street will be featured, each with a unique story, related in a unique style. Throughout the booklet, you will notice common references to places and people. It is hoped that you will enjoy learning about this ǯ ry. HISTORY OF DORSET - Written by Michael Woodside Ǥ ǯ always called Dorset, nor were many of the local Dzdz around the village called what they are called today. In the days of Zachariah Cole, back in the mid-nineteenth century, Dorset was called Cedar Narrows, so-called because squirrels could jump from one side of the narrows to the other by way of the dense stands of cedars lining the shallow waters.