XXTA Chapter 9.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DFW Media Guide Table of Contents

DFW Media Guide Table of Contents Introduction..................2 KHKS ........................ 14 KRVA ........................ 21 PR Tips and Tricks......... 2 KHYI ......................... 14 KSKY ........................ 22 Resources .....................3 KICI.......................... 14 KSTV......................... 22 Templates ................... 3 KJCR......................... 14 KTBK ........................ 22 Public Service KKDA ........................ 15 KTCK ........................ 22 Announcements............ 3 KKMR........................ 15 KTNO ........................ 22 PSA Format .............. 3 KLNO ........................ 15 KXEB ........................ 22 Tips for KLTY ......................... 15 KZEE......................... 22 Submitting PSAs....... 5 KLUV ........................ 15 KZMP ........................ 22 Press Releases ............. 6 KMEO........................ 15 WBAP........................ 22 Considerations KMQX........................ 15 Newspapers ............... 23 to Keep in Mind ......... 6 KNON........................ 15 Allen American ........... 23 Background Work ...... 6 KNTU ........................ 16 Alvarado Post ............. 23 Tips for Writing KOAI......................... 16 Alvarado Star ............. 23 a Press Release ......... 8 KPLX......................... 16 Azle News.................. 23 Tips for Sending KRBV ........................ 16 Benbrook Star ............ 23 a Press Release ......... 8 KRNB ........................ 16 Burleson Star ............. 23 Helpful -

Best Western Innsuites Hotel & Suites

Coast to Coast, Nation to Nation, BridgeStreet Worldwide No matter where business takes you, finding quality extended stay housing should never be an issue. That’s because there’s BridgeStreet. With thousands of fully furnished corporate apartments spanning the globe, BrideStreet provides you with everything you need, where you need it – from New York, Washington D.C., and Toronto to London, Paris, and everywhere else. Call BridgeStreet today and let us get to know what’s essential to your extended stay 1.800.B.SSTEET We’re also on the Global Distribution System (GDS) and adding cities all the time. Our GDS code is BK. Chek us out. WWW.BRIDGESTREET.COM WORLDWIDE 1.800.B.STREET (1.800.278.7338) ® UK 44.207.792.2222 FRANCE 33.142.94.1313 CANADA 1.800.667.8483 TTY/TTD (USA & CANADA) 1.888.428.0600 CORPORATE HOUSING MADE EASY ™ More than just car insurance. GEICO can insure your motorcycle, ATV, and RV. And the GEICO Insurance Agency can help you fi nd homeowners, renters, boat insurance, and more! ® Motorcycle and ATV coverages are underwritten by GEICO Indemnity Company. Homeowners, renters, boat and PWC coverages are written through non-affi liated insurance companies and are secured through the GEICO Insurance Agency, Inc. Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states or all GEICO companies. Government Employees Insurance Co. • GEICO General Insurance Co. • GEICO Indemnity Co. • GEICO Casualty Co. These companies are subsidiaries of Berkshire Hathaway Inc. GEICO: Washington, DC 20076. GEICO Gecko image © 1999-2010. © 2010 GEICO NEWMARKET SERVICES ublisher of 95 U.S. -

Brevard Live June 2010

Brevard Live June 2010 - 1 2 - Brevard Live June 2010 Brevard Live June 2010 - 3 4 - Brevard Live June 2010 Brevard Live June 2010 - 5 6 - Brevard Live June 2010 June 2010 • Volume 19, Issue 3 • Priceless FEATURES page 51 BREVARD LIVE MUSIC AWARDS SYBIL GAGE The nomination period is over. Thousands Until she was in her early twenties Sybil Columns of fans have nominated their favorite lo- Gage, or as she goes by now and then, Charles Van Riper cal musicians and now the actually voting Miss Feathers, resided in the wonderful- 22 Political Satire process has started. Fill out the ballot. ly diverse city of New Orleans. She now Page 8 lives and performs in Brevard County. Calendars Matt Bretz met up with her at Heidi’s. Live Entertainment, Page 20 CLASSIC ALBUMS LIVE 25 Theatre, Concerts, It’s summer vacation but the music at Festivals, Arts the King Center for the Performing Arts RON TEIXEIRA keeps on going. You can listen to your fa- This piano man ranks right up there as one vorite classic rock albums played note by Brevard Scene of Brevard’s best musicians. A deceptive- What’s hot in note in a live performance at very reason- ly relaxed stylist, the Berklee College of 34 able prices. Music graduate spent nearly 20 years as Brevard Page 11 a studio and jazz musician in New York City, before circling back to his former Out & About home in Florida.. Meet the places and PETER WHITE Page 37 37 the people He has maintained a reputation as one of the most versatile and prolific acous- Sex & The Beach tic guitarists on the contemporary jazz ED’S HEADS Relationship scene. -

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

PHILANTHROPY at the UNIVERSITY of ARIZONA 2017 in This Moment, All Over Campus, 10,000 Eager and Nervous Freshmen Are Trying to Find Theirin Classes

our moment PHILANTHROPY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 In this moment, all over campus, 10,000 eager and nervous freshmen are trying to find theirIn classes. They’re thisbeginning It's the first day of an experience that will shape the rest of their lives. the fall semester, moment, In this moment,Old Main President is right where Robert it’s C. always Robbins been. is Students nd beginningare his walking first school in front day of as it, 22 to andleader from of class. Maybe our prestigiousyou did institution. the same, Soon,and your he will support begin celebrates the an inclusivetraditions strategic we planning hold dear. process Or maybe that you support the UA engages thebecause entire you Wildcat recognize family the and special reimagines things our students the UA’s roleand facultyin our ever-evolving continue to accomplish. world. Whatever your reason, we appreciate it more than you know. Thank august 21, you for making our thriving community possible. As students and faculty begin their first day of fall semester, they’re busy and preoccupied. Regardless of In this moment, faculty are in labs, classrooms whether they see it on a daily basis, donors like you have and workspaces around campus. They’re inventing a positive impact on their work, their effort, and their the un-inventible. They’re expressing creativity. experiences on campus. You and your support make this They’re curing diseases, consulting with patients university great, and you make everything we accomplish and tackling society’s most daunting problems. 2017 possible. We hope, in this moment, that you feel how much you mean to the UA and everything it stands for. -

SIGNS on the Early Days of Radio and Television

TEXAS SIGNS ON The Early Days of Radio and Television Richard Schroeder Texas AÒM University Press College Station www.americanradiohistory.com Copyright CI 1998 by Richard Schroeder Manufactured in the United States of America All rights reserved First edition The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48 -1984. Binding materials have been chosen for durability. Library of Congress Cataloging -in- Publication Data Schroeder, Richard (Morton Richard) Texas signs on ; the early days of radio and television / Richard Schroeder. - ist ed. P. cm. - (Centennial series of the Association of Former Students, Texas A &M University ; no. 75) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN o-89o96 -813 -6 (alk. paper) t. Broadcasting-Texas- History. I. Title. II. Series. PN1990.6U5536 5998 384.54 o9764 -dcz1 97-46657 CIP www.americanradiohistory.com Texas Signs On Number Seventy-five: The Centennial Series of the Association of Former Students, Texas Ae'rM University www.americanradiohistory.com www.americanradiohistory.com To my mother Doris Elizabeth Stallard Schroeder www.americanradiohistory.com www.americanradiohistory.com Contents List of Illustrations ix Preface x1 Acknowledgments xv CHAPTERS i. Pre -Regulation Broadcasting: The Beginnings to 1927 3 z. Regulations Come to Broadcasting: 1928 to 1939 59 3. The War and Television: 1941 to 195o 118 4. The Expansion of Television and the Coming of Color: 195o to 196o 182 Notes 213 Bibliography 231 Index 241 www.americanradiohistory.com www.americanradiohistory.com Illustrations J. Frank Thompson's radios, 1921 II KFDM studio, 192os 17 W A. -

THE ARIZONA EXPERIMENT a Shift in Population, Money and Political Influence to America’S ‘Sunbelt States’ Is Helping to Reshape Its Research Universities

NEWS FEATURE NATURE|Vol 446|26 April 2007 Arizona State University’s president Michael Crow wants to shake up the hierarchy of American universities. THE ARIZONA EXPERIMENT A shift in population, money and political influence to America’s ‘sunbelt states’ is helping to reshape its research universities. The first of two features looks at the far-reaching ambitions of Arizona State University. The second asks whether a rush to create extra medical schools could spread the region’s resources too thinly. t is a hot February morning in the Arizona ties, and instead build up excellence at problem- its content to please Ira Fuller, a Mormon con- desert, and Walter Cronkite, the legendary focused, interdisciplinary research centres. US struction magnate who has donated more than American newscaster, is straining every research universities, Crow argues, “are at a fork US$160 million to various university projects. Imuscle in his 90-year-old body to break in the road: do you replicate what exists, or do Before arriving at ASU, Crow had a reputation C. CARLSON/AP the hard ground with a golden shovel. you design what you actually need?” By his reck- as a talented but headstrong university leader. Cronkite is in Phoenix to start construction oning, centres that teach students to communi- A political scientist who specialized in science on a new home for America’s biggest journal- cate with the public and to tackle real problems, and technology policy at Iowa State University, ism school, in America’s largest university, in such as water supply, are more relevant to today’s he entered full-time university administration as what will soon be its third-largest city. -

Report on Population Viability Analysis Model Investigations of Threats to the Southern Resident Killer Whale Population from Trans Mountain Expansion Project

Report on Population Viability Analysis model investigations of threats to the Southern Resident Killer Whale population from Trans Mountain Expansion Project Prepared for: Raincoast Conservation Foundation Prepared by: Robert C. Lacy, PhD Senior Conservation Scientist Chicago Zoological Society Kenneth C. Balcomb III Executive Director and Senior Scientist Center for Whale Research Lauren J.N. Brent, PhD Associate Research Fellow, Center for Excellence in Animal Behaviour, University of Exeter Postdoctoral Associate, Centre for Cognitive Neuroscience, Duke University Darren P. Croft, PhD Associate Professor of Animal Behaviour University of Exeter Christopher W. Clark, PhD Imogene P. Johnson Senior Scientist, Bioacoustics Research Program, Cornell Lab of Ornithology Senior Scientist, Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, Cornell University Paul C. Paquet Senior Scientist Raincoast Conservation Foundation Table of Contents Page 1.0. Introduction 1 2.0. PVA Methodology 3 2.1. The Population Viability Analysis (PVA) modeling approach 6 2.2. About the Vortex PVA software 6 2.3. Input variables used in developing the Vortex PVA model for the Southern Resident population 13 3.0 Results of modelling 13 3.1. Projections for the Southern Resident population under the status quo (baseline model) 17 3.2. Sensitivity testing of important model parameters 18 3.3. Examination of potential threats 18 4.0. Conclusions 36 5.0. Literature Cited 38 Appendix A Review of Previous Southern Resident Population Viability Analyses Appendix B Curriculum vitae Dr. Robert C. Lacy, Ph.D. Appendix B Biography Kenneth C. Balcomb III Appendix C Curriculum vitae Laruen J.N. Brent, Ph.D. Appendix D Curriculum vitae Darren P. Croft, Ph.D. -

The Bern Nix Trio:Alarms and Excursions New World 80437-2

The Bern Nix Trio: Alarms and Excursions New World 80437-2 “Bern Nix has the clearest tone for playing harmolodic music that relates to the guitar as a concert instrument,” says Ornette Coleman in whose Prime Time Band Nix performed from 1975 to 1987. Melody has always been central to Nix's musical thinking since his youth in Toledo, Ohio, where he listened to Duane Eddy, The Ventures, Chet Atkins, and blues guitarist Freddie King. When his private instructors Don Heminger and John Justus played records by Wes Montgomery, Charlie Christian, Django Reinhardt, Barney Kessel, and Grant Green, Nix turned toward jazz at age fourteen. “I remember seeing Les Paul on TV. I wanted to play more than the standard Fifties pop stuff. I liked the sound of jazz.” With Coleman's harmolodic theory, jazz took a new direction—in which harmony, rhythm, and melody assumed equal roles, as did soloists. Ever since Coleman disbanded the original Prime Time Band in 1987, harmolodics has remained an essential element in Nix's growth and personal expression as a jazz guitarist, as evidenced here on Alarms and Excursions—The Bern Nix Trio. The linear phrasing and orchestral effects of a jazz tradition founded by guitarists Charlie Christian, Grant Green and Wes Montgomery are apparent in Nix's techniques, as well as his clean-toned phrasing and bluesy melodies. Nix harks back to his mentors, but with his witty articulation and rhythmical surprises, he conveys a modernist sensibility. “I paint a mustache on the Mona Lisa,” says Nix about his combination of harmolodic and traditional methods. -

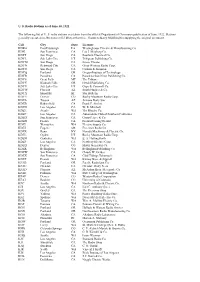

U. S. Radio Stations As of June 30, 1922 the Following List of U. S. Radio

U. S. Radio Stations as of June 30, 1922 The following list of U. S. radio stations was taken from the official Department of Commerce publication of June, 1922. Stations generally operated on 360 meters (833 kHz) at this time. Thanks to Barry Mishkind for supplying the original document. Call City State Licensee KDKA East Pittsburgh PA Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co. KDN San Francisco CA Leo J. Meyberg Co. KDPT San Diego CA Southern Electrical Co. KDYL Salt Lake City UT Telegram Publishing Co. KDYM San Diego CA Savoy Theater KDYN Redwood City CA Great Western Radio Corp. KDYO San Diego CA Carlson & Simpson KDYQ Portland OR Oregon Institute of Technology KDYR Pasadena CA Pasadena Star-News Publishing Co. KDYS Great Falls MT The Tribune KDYU Klamath Falls OR Herald Publishing Co. KDYV Salt Lake City UT Cope & Cornwell Co. KDYW Phoenix AZ Smith Hughes & Co. KDYX Honolulu HI Star Bulletin KDYY Denver CO Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZA Tucson AZ Arizona Daily Star KDZB Bakersfield CA Frank E. Siefert KDZD Los Angeles CA W. R. Mitchell KDZE Seattle WA The Rhodes Co. KDZF Los Angeles CA Automobile Club of Southern California KDZG San Francisco CA Cyrus Peirce & Co. KDZH Fresno CA Fresno Evening Herald KDZI Wenatchee WA Electric Supply Co. KDZJ Eugene OR Excelsior Radio Co. KDZK Reno NV Nevada Machinery & Electric Co. KDZL Ogden UT Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZM Centralia WA E. A. Hollingworth KDZP Los Angeles CA Newbery Electric Corp. KDZQ Denver CO Motor Generator Co. KDZR Bellingham WA Bellingham Publishing Co. KDZW San Francisco CA Claude W. -

Reality Check of TC Boyle's Terranauts

Reality Check of TC Boyle’s Terranauts “Welcome to Ecosphere-2! We are going to have our first child, E-2’s first child and we are absolutely thrilled!” (Dawn Chapman)…..”There are 48 closures to come [of 2 years duration each] after this one and by then, in 97 years time I have no doubts we’ll be doing this on Mars in earnest and for real, and all the children of E-2 (Ecosphere-2) like our son, will be pioneers to the stars.” (Ramsey Roothoorp, Dawn’s husband), Dawn and Ramsey proudly announced to the stunned reporters during mission two, the second 2 year closure in the ecosphere, revealing the unplanned birth of his and Dawn’s baby during the “closure period”. [1] With “nothing in, nothing out”, only using the hermetically sealed resources of the E-2 ecosphere and the support of their 6 fellow-terranauts i.e., 3 male and 3 female crew mates, this closely resembles the scenario of one of the Mars colonization plans predicted to happen within the next decades of our century. This is the setup of Boyle’s latest bestseller. It raised my interest from an space-operational point of view, because knowing Boyle, he has researched his subject very thoroughly and combined real occurrences with his own imagination to analyze and describe the terranaut’s crew group dynamics behavior during the “next step” i.e., the giving of birth in a closed self-sustaining environment independent from Earth’s. This scenario has a very real background because the “Mars One” mission plans to establish a permanent human colony on Mars by 2025, promoted by the private spaceflight project led by Dutch entrepreneur Bas Lansdorp (see also Mission One description below). -

List of Radio Stations in Texas

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia List of radio stations in Texas From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page The following is a list of FCC-licensed AM and FM radio stations in the U.S. state of Texas, which Contents can be sorted by their call signs, broadcast frequencies, cities of license, licensees, or Featured content programming formats. Current events Random article Contents [hide] Donate to Wikipedia 1 List of radio stations Wikipedia store 2 Defunct 3 See also Interaction 4 References Help 5 Bibliography About Wikipedia Community portal 6 External links Recent changes 7 Images Contact page Tools List of radio stations [edit] What links here This list is complete and up to date as of March 18, 2019. Related changes Upload file Call Special pages Frequency City of License[1][2] Licensee Format[3] sign open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com sign Permanent link Page information DJRD Broadcasting, KAAM 770 AM Garland Christian Talk/Brokered Wikidata item LLC Cite this page Aleluya Print/export KABA 90.3 FM Louise Broadcasting Spanish Religious Create a book Network Download as PDF Community Printable version New Country/Texas Red KABW 95.1 FM Baird Broadcast Partners Dirt In other projects LLC Wikimedia Commons KACB- Saint Mary's 96.9 FM College Station Catholic LP Catholic Church Languages Add links Alvin Community KACC 89.7 FM Alvin Album-oriented rock College KACD- Midland Christian 94.1 FM Midland Spanish Religious LP Fellowship, Inc.