Evaluation of Volume and Quality of Social Performance Indicators Disclosure of Companies Included in Belexline Index

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expat Capital – the Etf Provider for Cee Countries

Market data as of 21 May 2020 EXPAT CAPITAL – THE ETF PROVIDER FOR CEE COUNTRIES Expat Asset Management has created a family of exchange traded funds (ETFs) covering the equity markets in 11 countries in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). Expat’s ETF products are unique market propositions providing country-specific exposure in the CEE region to international investors. Chart 1. Expat’s 11 ETFs on the Map of Europe Source: Expat Asset Management Table 1. The List of All ETFs Managed by Expat Asset Management CURRENCY No. COUNTRY FUND NAME INDEX EXPOSURE 1 Poland Expat Poland WIG20 UCITS ETF WIG20 PLN 2 Czech Republic Expat Czech PX UCITS ETF PX CZK 3 Slovakia Expat Slovakia SAX UCITS ETF SAX EUR 4 Hungary Expat Hungary BUX UCITS ETF BUX HUF 5 Slovenia Expat Slovenia SBI TOP UCITS ETF SBI TOP EUR 6 Croatia Expat Croatia CROBEX UCITS ETF CROBEX HRK 7 Serbia Expat Serbia BELEX15 UCITS ETF BELEX15 RSD 8 North Macedonia Expat Macedonia MBI10 UCITS ETF MBI10 MKD 9 Romania Expat Romania BET UCITS ETF BET RON 10 Bulgaria Expat Bulgaria SOFIX UCITS ETF SOFIX BGN 11 Greece Expat Greece ASE UCITS ETF ATHEX Composite EUR Source: Expat Asset Management Expat Capital Bulgaria, Sofia 1000, 96A G. S. Rakovski Str.; +359 2 980 1881; [email protected]; www.expat.bg 1 Market data as of 21 May 2020 Expat’s ETF products are designed to be major highways for capital flows to and from the equity markets of the CEE countries. They link the stock exchanges of those countries with the financial centres of London and Frankfurt, making it easy and cost-effective for international investors to take and liquidate an exposure to the specific countries in the region. -

Do Serbian Companies Provide Relevant Disclosures About Goodwill?

ECONOMIC THEMES (2018) 56(1): 127-138 DOI 10.2478/ethemes-2018-0008 DO SERBIAN COMPANIES PROVIDE RELEVANT DISCLOSURES ABOUT GOODWILL? Dejan Spasić University of Niš, Faculty of Economics, Republic of Serbia [email protected] UDC Abstract: IFRS 3 have been adopted to increase the relevance of 657 information on business combinations. Consequently, it is expected that information on goodwill will contribute to that goal. By analysing Original the sample of the most important companies in the Republic of Serbia, scientific this paper identifies several key areas of disclosure regarding paper recognition, initial recognition, and subsequent measurement of goodwill. All companies listed on the Belgrade Stock Exchange (BSE) which prepare consolidated financial statements are taken for the sample. In addition, the paper includes selected non-listed companies (that are most important for the Serbian economy according to the criteria of revenue, number of employees, and the share in the total GDP) in the sample. The final sample consists of 156 consolidated financial statements of 43 groups in the analysed four-year period (2013-2016). Descriptive statistic is used. The author found a low level of disclosure, which is further accompanied by misapplication of IFRS. Received: Keywords: Goodwill, IFRS, relevance, disclosures, impairment test, 05.03.2018 impairment loss, amortisation Accepted: JEL classification: M41, G32, G34 27.03.2018 1. Introduction In the modern business environment intangible assets (including goodwill) play an important role. Nevertheless, the interest to interpret the essence of goodwill and its accounting scope has existed for over a hundred years. In this regard, Brunovs and Kirsch (1991) state that Hughes, in his 1982 study, identified trade and legal guidelines regarding goodwill much earlier, in 1417. -

143 Belgrade Stock Exchange

EKONOMSKI HORIZONTI, 2011, 13, (1) str. 143-154 Stru čni članak 336.761(497.11) ∗ Jelena Purić BELGRADE STOCK EXCHANGE: Post-Crisis Economy- lessons and possibillites Abstract: The first ideas about establishing an organization the purpose of which would be to control the money minimum appeared during the 30es of the 19 th century in Serbia. Since then many laws have been made, many meetings have been held and as many reforms have been carried out. The last decade is considered to be the turning point in the development of the Belgrade stock exchange. Namely, there has been an improvement of the development of the trading systems; the cooperation with other developed stock exchange markets in the neighbouring countries has been intensified, the first index of the BelexFm has been made and the improvement of the cooperation with the improvement of the relationship with the entities who issue securities and bonds, which lead to the first listing of shares. Key words : stock exchange, prime market, turnover, indexes JEL Classification: G20 INTRODUCTION Stock market is a place where authorized persons trade in standardized goods according to established rules. In all its complexity and diversity the stock market did not emerge as a product of pre-planned actions. It was created primarily as a result of a series of spontaneous and accidental circumstances, at a time when business scale of the traders grows over their individual abilities and directs them toward each other to jointly promote business in all aspects of mediation. As the original mediative circle formed the basic forms of future organizations, thus spontaneity constricted in further act, and to the extent necessary to develop the organization of stock exchange activity in order to meet the challenges of the changing environment. -

Mesečni Izveštaj / Monthly Report Decembar 2019. Indeksi / Indices

MESEČNI PROMET / MONTHLY TURNOVER Promet RSD / Promena % / Promet EUR / Promena % / Broj transakcija / TRŽIŠNI SEGMENT / MARKET SEGMENT Turnover RSD % Change (RSD)* Turnover EUR % Change (EUR)* No of Transactions PRIME LISTING-akcije 94,109,931 -16.79% 800,673 -16.80% 1,413 PRIME LISTING-obveznice Republike Srbije 9,635,318,713 +1,087.86% 81,985,441 +1,087.94% 21 STANDARD LISTING-akcije 110,045,894 -99.57% 936,131 -99.57% 173 OPEN MARKET—akcije 23,568,588 -99.16% 200,519 -99.16% 292 MTP—akcije 43,301,493 -85.49% 368,424 -85.49% 323 * mesečna promena / * monthly change Promet RSD / Promena % / Promet EUR / Promena % / Broj transakcija / METODE TRGOVANJA / TRADING METHODS Turnover RSD % Change (RSD)* Turnover EUR % Change (EUR)* No of Transactions Kontinuirano trgovanje / Continuous trading method 9,887,058,619 +138.83% 84,127,089 +138.75% 2,218 Blok trgovanja / Block trading 19,286,000 -99.92% 164,099 -99.92% 4 Ukupno / Total 9,906,344,619 -66.63% 84,291,188 -66.62% 2,222 * mesečna promena / * monthly change Učešće u ukupnom Učešće u ukupnom broju Učešće u prometu Učešće u broju STRUKTURA TRGOVANJA / prometu / Total transakcija / Total No. Of akcijama / Turnover - transakcija akcijama / TRADING STRUCTURE Turnover Trades Shares No of Trades - Shares Regulisano tržište / Regulated Market 99.56% 85.46% 84.02% 85.32% MTP 0.44% 14.54% 15.98% 14.68% METODE TRGOVANJA / TRADING METHODS Kontinuirano trgovanje / Continuous trading 99.81% 99.82% 92.88% 99.82% Blok trgovanja / Block trading 0.19% 0.18% 7.12% 0.18% VRSTE HOV / SECURITY TYPE Akcije / Shares 2.74% 99.05% - - Obveznice Republike Srbije / RS Bonds 97.26% 0.95% - - Korporativne obveznice / Corporate Bonds 0.00% 0.00% - - INDEKSI / INDICES BELEX15 2.09% 71.33% 76.26% 72.01% BELEXline 2.36% 85.87% 86.40% 86.69% PROMET U PRETHODNIH 12 MESECI / TURNOVER IN PREVIOUS 12 MONTHS Regulisano / Regulated Br. -

Mesečni Izveštaj / Monthly Report Jun 2020. Indeksi / Indices

MESEČNI PROMET / MONTHLY TURNOVER Promet RSD / Promena % / Promet EUR / Promena % / Broj transakcija / TRŽIŠNI SEGMENT / MARKET SEGMENT Turnover RSD % Change (RSD)* Turnover EUR % Change (EUR)* No of Transactions PRIME LISTING-akcije 42,465,151 -32.18% 361,132 -32.18% 1,364 PRIME LISTING-obveznice Republike Srbije 1,085,087,349 -62.57% 9,227,925 -62.57% 9 STANDARD LISTING-akcije 156,724,559 +16.64% 1,332,866 +16.65% 96 OPEN MARKET—akcije 61,939,404 +14.22% 526,746 +14.23% 199 MTP—akcije 18,295,881 +505.44% 155,601 +505.48% 194 * mesečna promena / * monthly change Promet RSD / Promena % / Promet EUR / Promena % / Broj transakcija / METODE TRGOVANJA / TRADING METHODS Turnover RSD % Change (RSD)* Turnover EUR % Change (EUR)* No of Transactions Kontinuirano trgovanje / Continuous trading method 1,359,171,445 -56.89% 11,558,844 -56.89% 1,859 Blok trgovanja / Block trading 5,340,899 +100.00% 45,426 +100.00% 3 Ukupno / Total 1,364,512,344 -56.73% 11,604,270 -56.72% 1,862 * mesečna promena / * monthly change Učešće u ukupnom Učešće u ukupnom broju Učešće u prometu Učešće u broju transakcija STRUKTURA TRGOVANJA / prometu / Total transakcija / Total No. Of akcijama / Turnover - akcijama / No of Trades - TRADING STRUCTURE Turnover Trades Shares Shares Regulisano tržište / Regulated Market 98.66% 89.58% 93.45% 89.53% MTP 1.34% 10.42% 6.55% 10.47% METODE TRGOVANJA / TRADING METHODS Kontinuirano trgovanje / Continuous trading 99.61% 99.84% 98.09% 99.84% Blok trgovanja / Block trading 0.39% 0.16% 1.91% 0.16% VRSTE HOV / SECURITY TYPE Akcije / Shares 20.48% 99.52% - - Obveznice Republike Srbije / RS Bonds 79.52% 0.48% - - Korporativne obveznice / Corporate Bonds 0.00% 0.00% - - INDEKSI / INDICES BELEX15 18.41% 83.73% 89.90% 84.13% BELEXline 19.03% 87.54% 92.92% 87.97% PROMET U PRETHODNIH 12 MESECI / TURNOVER IN PREVIOUS 12 MONTHS Regulisano / Regulated Br. -

Dnevni Izveštaj 0 2 . O K T O B a R 2012

Dnevni izveštaj 0 2 . o k t o b a r 2012 PREGLED AKTIVNOSTI NA BEOGRADSKOJ BERZI KALENDAR DEŠAVANJA 5. oktobar Indeks najlikvidnijih akcija BELEX15 je umanjen za 0,3% u odnosu na jučerašnje trgovanje, Uprava za trezor: Aukcija 6-m zapisa 9. oktobar dok je kompozitni indeks BELEXline ostao na praktično nepromenjenoj vrednosti. Akcije NBS: Sednica Izvršnog odbora kompanija TE-TO (20%) i Impol Seval (7,5%) su zabeležile najveći rast, dok su najveći pad 11. oktobar zabeležile akcije kompanija Galenika fitofarmacija (-7,8%) i BB Minaqua (-4,2%). NIS je bila Uprava za trezor: Aukcija 3-m zapisa najaktivnija akcija na trgovanju sa prometom od 3,8 miliona dinara. Učešće inostranih 12. oktobar investitora u trgovanju akcijama iznosilo je 23,4%. Zavod za statistiku: Inflacija (septembar) KORPORATIVNE VESTI BELEXline NAFTNA INDUSTRIJA SRBIJE <NIIS SG Equity> 700 1,500 Cena: RSD 620 Tržišna kap.; RSD 101.097m YTD: 2,5% Prosečan 3m promet; RSD 5,5m 600 1,400 500 1,300 Vlada planira povećanje rudne rente za eksploataciju nafte i gasa Ministar rudarstva Milan Bačević je izjavio da vlada priprema predlog novog zakona o 400 1,200 rudarstvu za novembar koji bi predviđao povećanje rudne rente za eksploataciju nafte i gasa. 300 1,100 Trenutno, prema međudržavnom ugovoru između Srbije i Rusije, NIS plaća rudnu rentu u 200 1,000 iznosu od 3% do završetka projekta modernizacije rafinerije u Pančevu. U prvoj polovini 100 900 godine, troškovi NIS-a za rudnu rentu su iznosili 1,4 milijardi dinara, dok je u 2011. i 2010. 0 800 Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep godini ovaj porez iznosio 2,1 milijardu i 1,4 milijardi dinara, respektivno. -

Makenzijeva 23, Belgrade, Serbia Phone +381113809983; Fax:+381113837600; E-Mail: [email protected] Find Us on Bloomberg and Thompson Reuters

Makenzijeva 23, Belgrade, Serbia Phone +381113809983; Fax:+381113837600; E-mail: [email protected] Find us on Bloomberg and Thompson Reuters Wrap Up The Belgrade Stock Exchange ended this 3 day work week with poor liquidity, and lower volume than last week, 894thousands vs 3.8mn EUR in previous week. The Belex15 went down 1.08% to 493.68 points, and Belexline finished the week with 8.91% drop, at 968.28 points. Number of active issues this week was 55, of which 12 posted gains, 18 posted losses and 25 issues finished without a price change. Foreign investor overall participation was 59.97%, with 69.44% of the buy side volume and 50.51% of selling volume. The winners for the year were Univerzal Banka a.d Beograd (UNBN) +6.98%, Jubmes banka a.d. Beograd (JMBN) +3.42%, Veterinarski zavod Subotica a.d. Subotica (VZAS) +1.56%. Losers of the year were Agrobanka a.d. Beograd (AGBN) - 17.88%, Jedinstvo Sevojno a.d. Sevojno (JESV) -4.08%, Tigar a.d. Pirot (TIGR) -3.06%. Naftna Industrija Srbije (NIIS) ended the week with low volume and weak activity and investor interest. Aerodrom Nikola Tesla (AERO) decline in prices with drastically reduced turnover. Energoprojekt Holding (ENHL) as last week, traded with a bigger package than 10,000 pieces. Price was on the same level in anticipation of the continuation of shareholders assembly that will be held on 12.01. In Fix Income and FX: The Dinar declined 0.59% against the euro, ending the week at 105.25 At Thursday’s auction it sold over 5.92 billion dinars worth of 6m Treasury bills, or 98.68% of the total offer. -

Tržišne Informacije Pregled Stanja Na Svetskim

27.11.2015 . Tržišne informacije Tržište novca KAMATA NA MEDJUBANKARSKE DEPOZITE LIBOR EURIBOR 1 DAN 1 MESEC 3 MESECA 6 MESECI 1 GODINA USD EUR CHF BID USD 0,15 0,200,82 0,92 0,84 1 MESEC 0,23150 -0,15857 -0,80000 EURIBOR1MD -0,156 EUR -0,27 -0,26 -0,19 -0,13 -0,01 2 MESECA 0,31800 -0,12714 -0,80900 EURIBOR2MD -0,119 CHF -0,90 -1,00 -1,04 -1,09 -0,89 3 MESECA 0,40670 -0,11286 -0,80900 EURIBOR3MD -0,104 GBP 0,40 0,42 0,65 0,84 1,05 6 MESECI 0,64865 -0,04357 -0,78200 EURIBOR6MD -0,031 JPY -0,1500 -0,10 -0,10 -0,07 0,05 1 GODINA 0,973350,04571 -0,69500 EURIBOR1YD 0,060 NAPOMENA: Podaci za LIBOR su od pre 48 sati. BELIBOR BEONIA KAMATNE STOPE RAZNO CENTRALNIH BANAKA RSD EFEKTIVNA STOPA IZNOS POZAJMICE u mio rsd VALUTA STOPA Vrednost u USD 2 NEDELJE 3,40 2,56 1.350 USD 0,25 Zlato - TROY OUNCE 1.068,21 1 MESEC 3,55 EUR 0,05 Srebro - TROY OUNCE 14,13 3 MESECA 3,89 5 YEAR CREDIT DEFAULT SWAP CHF -0,75 Brent nafta - BAREL 42,89 6 MESECI 4,09 285 RSD 4,50 Napomena: 1 TROY OUNCA = 31,1034768 gr Napomena: 1 BAREL = 158,9873 l Kursna lista Kursna lista na dan 27.11.2015 FIXING REPO Iznos u mlrd RSD KAMATA % USD/RSD EUR/RSD CHF/RSD 7D 50,00 2,51 114,0473 121,1296 111,3835 promena današnjeg kursa u odnosu na prethodni dan DRŽAVNI ZAPISI Iznos u mio RSD DISKONTNA STOPA % RSD% RSD % RSD % 3 M 3.000,00 2,94 0,060,05 0,07 0,06 -0,02 -0,02 6 M 3.000,00 4,09 promena današnjeg kursa u odnosu na prethodni mesec 12 M 10.000,00 4,09 RSD % RSD % RSD % DRŽAVNE KUPONSKE OBVEZNICE (RSD) Iznos u mio RSD PRINOS % 4,11 3,73 0,370,31 0,32 0,29 2 Y (6%) 11.173,00 4,95 promena današnjeg kursa u odnosu na 31.12.2014. -

Weekly Report

INTERCITY BROKER JSC WEEKLY REPORT BROKER-DEALER COMPANY Member of Belgrade Stock Exchange s t t h Member of Central Securities Depository and Clearing house S e pt emb er 21 – S ep t embe r 25 , 2 009 52 Maksima Gorkog St., Belgrade, Serbia Tel: +381 (11) 3083-100, 3087-862; Fax: +381 (11) 3083-150 e-mail: [email protected]; www.icbbg.rs Volumes Up, Fortnight Rally Stopped On Friday BSE indices fell on Friday, after 15 days of continuous growth, following the world stock markets reduction caused by the G20 Fluctuation of Stock Exchange Indices Summit. Nevertheless, the week behind us was very good for the (%) in the Region (1-m Change) BSE – the indices went up and the overall turnover increased by 20 55% mainly due to transactions of AIK Bank, which was by far the most traded security. The blue chip index Belex15 increased 3.43% and broader Belexline 2.57%. The penetration of foreign 16 institutional investors is evident as well as significantly larger activity of the “old” foreign investors on the buy side. 12 Serbian central bank (NBS) expects 6.0% inflation next year with a variation band of 2% on either side. Key repo rate stays at 12%. 8 Serbia's retail market is expected to start picking up in the spring of 2010 while supply of office space in Belgrade will further exceed demand levels by the end of 2009 while rent rates are expected to 4 decrease, Colliers International said in a recent market overview. Public company Transnafta signed the Letter of intent with US 0 company Comico Oil which wants to build a new oil refinery in Smederevo. -

Serbian Daily 2 7 J U N E 2012

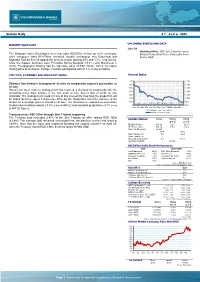

Serbian Daily 2 7 J u n e 2012 UPCOMING EVENTS AND DATA MARKET SNAPSHOT June 29 Statistics Office: GDP (Q1), Industrial output, The Belgrade Stock Exchange’s blue-chip index BELEX15 inched up 0.2% yesterday, External Trade, Retail Trade (May) Labor Force while composite index BELEXline remained virtually unchanged. Inex Buducnost and Survey (April) Sajkaska Fabrika Secera topped the winners’ board, gaining 20% and 1.5%, respectively, while the biggest decliners were Privredna Banka Beograd (-9.4%) and Montinvest (- 3.5%). Energoprojekt Holding had the top trade value of RSD 30.4m, with a 1% higher closing price of its shares. Foreign investors participated with 21.1% in equity trading. General Index POLITICS, ECONOMY AND INDUSTRY NEWS 700 1,500 Zelezara Smederevo’s management decides to temporarily suspend production as 600 1,400 of July 500 1,300 Smederevo steel maker’s management has reached a decision to temporarily idle the 400 1,200 remaining active blast furnace in the first week of July, due to lack of funds for raw 300 1,100 materials. The management could not say at this moment for how long the production will be halted, but they expect it to become active by late September when the outcome of the 200 1,000 tender for a strategic partner should be known. The shutdown is expected to exacerbate 100 900 Serbia’s deteriorating exports (-3.5% y-o-y in 4M’12) and industrial production (-4.7% y-o-y 0 800 in 4M’12) figures. Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May BELEXline Volume (LHS, in RSD m) BELEXline Closing Price (RHS) Treasury raises RSD 365m through 36m T-bonds reopening The Treasury sold yesterday 2.42% of the 36m T-bonds on offer, raising RSD 365m Serbian Market Close Chng Chng (€2.9m). -

Dnevni Izveštaj 4 . M a J 2012

Dnevni izveštaj 4 . m a j 2012 KALENDAR DEŠAVANJA PREGLED AKTIVNOSTI NA BEOGRADSKOJ BERZI 7. maj Uprava za trezor: Aukcija 24-m trezorskih zapisa Na jučerašnjem trgovanju indeks najlikvidnijih akcija BELEX 15 je umanjen za 0,8%, dok je kompozitni indeks BELEXline snižen za 0,3%. Pobednici dana su Komercijalna banka (3,9%) i Sojaprotein (1,3%), dok su najviše pale akcije Jubmes banke (-9,6%) i Jedinstvo Sevojno (- 8,2%). Najveći promet je zabeležen akcijama kompanije Sojaprotein (RSD 14,7 miliona). Učešće inostranih investitora u trgovanju akcijama iznosilo je 27,7%. BELEXline VESTI IZ POLITIKE I EKONOMIJE 700 1,600 600 1,500 Uprava za trezor prikupila 2,3 milijardi dinara prodajom šestomesečnih državnih 500 1,400 zapisa 400 1,300 Uprava za trezor prodala je juče 46,3% obima aukcije šestomesečnih državnih zapisa, čime 300 1,200 je prikupila 2,3 milijardi dinara (20,7 miliona evra). Kamatna stopa ostala na istom nivou u odnosu na prethodnu aukciju i iznosila je 10,48%. 200 1,100 100 1,000 KORPORATIVNE VESTI 0 900 May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr BELEXline Volume (LHS, in RSD m) BELEXline Closing Price (RHS) Izvršen prenos besplatnih akcija Telekoma Srbija Na osnovu zaključka Vlade Srbije, Centralni registar hartija od vrednosti izvršio je juče upis Podaci sa berze Promena Promena akcija Telekoma Srbija. Od ukupno mililardu akcija Telekoma, Republika Srbija i Telekom Vrednost d-t-d* y-t-d** Srbija su vlasnici udela od 58,11% odnosno 20%, dok su zaposleni i bivši zaposleni te BELEX15 indeks 487,20 -0,8% -2,4% kompanije dobili 6,94%, a građani 14,95% akcija. -

Belgrade Stock Exchange

Serbian Capital Market Belgrade Stock Exchange 0 Legal frame of listed companies Belgrade Stock Market is still the market in transition, where only the companies that went through privatization process are being listed. Law on Ownership Transformation Law on Privatization Law on the Right to Free Shares 1 Market Characteristics High ownership concentration Low liquidity Attractive fundamentals IPO still not introduced 2 Brief Market Overview 2016 Overview - The year 2016 brought EUR 361m in total trade volume, which is the highest amount since 2009, with only EUR 52,5m generated from stocks. - Lack of attractive growth profiles among domestic blue chips, delisting of Imlek, TOB of AIK Banka and still relatively attractive yield for government notes (given the risk profile), are among reasons for dramatic drop in trade volume in case of stocks. - After initial drop in January 2016, both BELEX15 and BELEXline established an uptrend by the end of the year, thus annual change was plus 11.4% and 13.7%, respectively. However, most of annual jump was seen in 4Q, with Energoprojekt (ENHL), NIS (NIIS) and Tehnogas (TGAS) among top gainers. Annual trade volumes at BSE 2006-2016 in EUR m 10.0 Monthly turnovers in 2016 (EUR m) - only stocks 2,500 9.0 8.4 8.0 2,000 7.3 7.0 6.6 Bonds Stocks 6.0 1,500 5.0 4.7 4.0 3.8 1,000 3.3 3.4 3.2 3.1 3.0 2.9 3.0 2.1 2.0 500 1.0 0 0.0 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 3 Belex15 Overview .