Style in Music Roger B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Music Theory

Introduction to Music Theory This pdf is a good starting point for those who are unfamiliar with some of the key concepts of music theory. Reading musical notation Musical notation (also called a score) is a visual representation of the pitched notes heard in a piece of music represented by dots over a set of horizontal staves. In the top example the symbol to the left of the notes is called a treble clef and in the bottom example is called a bass clef. People often like to use a mnemonic to help remember the order of notes on each clef, here is an example. Intervals An interval is the difference in pitch between two notes as defined by the distance between the two notes. The easiest way to visualise this distance is by thinking of the notes on a piano keyboard. For example, on a C major scale, the interval from C to E is a 3rd and the interval from C to G is a 5th. Click here for some more interval examples. It is also common for an increase by one interval to be called a halfstep, or semitone, and an increase by two intervals to be called a whole step, or tone. Joe ReesJones, University of York, Department of Electronics 19/08/2016 Major and minor scales A scale is a set of notes from which melodies and harmonies are constructed. There are two main subgroups of scales: Major and minor. The type of scale is dependant on the intervals between the notes: Major scale Tone, Tone, Semitone, Tone, Tone, Tone, Semitone Minor scale Tone, Semitone, Tone, Tone, Semitone, Tone, Tone For example (by visualising a keyboard) the notes in C Major are: CDEFGAB, and C Minor are: CDE♭FGA♭B♭. -

How to Effectively Listen and Enjoy a Classical Music Concert

HOW TO EFFECTIVELY LISTEN AND ENJOY A CLASSICAL MUSIC CONCERT 1. INTRODUCTION Hearing live music is one of the most pleasurable experiences available to human beings. The music sounds great, it feels great, and you get to watch the musicians as they create it. No matter what kind of music you love, try listening to it live. This guide focuses on classical music, a tradition that originated before recordings, radio, and the Internet, back when all music was live music. In those days live human beings performed for other live human beings, with everybody together in the same room. When heard in this way, classical music can have a special excitement. Hearing classical music in a concert can leave you feeling refreshed and energized. It can be fun. It can be romantic. It can be spiritual. It can also scare you to death. Classical music concerts can seem like snobby affairs full of foreign terminology and peculiar behavior. It can be hard to understand what’s going on. It can be hard to know how to act. Not to worry. Concerts are no weirder than any other pastime, and the rules of behavior are much simpler and easier to understand than, say, the stock market, football, or system software upgrades. If you haven’t been to a live concert before, or if you’ve been baffled by concerts, this guide will explain the rigmarole so you can relax and enjoy the music. 2. THE LISTENER'S JOB DESCRIPTION Classical music concerts can seem intimidating. It seems like you have to know a lot. -

Gossett Dissertation

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Music VALUES TO VIRTUES: AN EXAMINATION OF BAND DIRECTOR PRACTICE A Dissertation in Music Education by Jason B. Gossett © 2015 Jason B. Gossett Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August, 2015 ii The dissertation of Jason B. Gossett was reviewed and approved* by the following: Linda Thornton Associate Professor, Music Education Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Richard Bundy Professor, Music Education Davin Carr-Chellman Assistant Professor, Adult Education Joanne Rutkowski Professor, Music Education Graduate Program Chair *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT The purpose of this dissertation was to investigate the pedagogic values of band directors. Further, how these values are operationalized in the classroom and contribute to a director’s conception of the good life was examined. This dissertation contains the findings from three separate investigations. The purpose of the first investigation was to elicit and examine the pedagogic values of three band directors. I sought to understand their pedagogic values through observation, interviews, and examination of repertoire lists. The participants’ pedagogic values emerged as values of ends and of students. Directors identified undergraduate music education experiences, reflection, and teaching experiences as sources of their values. The purpose of my second investigation was to ascertain the values and sources of pedagogic values held by band directors and how contextual factors influence stasis or change in values. I used a descriptive survey design for this inquiry. Participants were band directors from six states representing the six National Association for Music Education regional divisions. -

Anexo:Premios Y Nominaciones De Madonna 1 Anexo:Premios Y Nominaciones De Madonna

Anexo:Premios y nominaciones de Madonna 1 Anexo:Premios y nominaciones de Madonna Premios y nominaciones de Madonna interpretando «Ray of Light» durante la gira Sticky & Sweet en 2008. La canción ganó un MTV Video Music Awards por Video del año y un Grammy a mejor grabación dance. Premios y nominaciones Premio Ganados Nominaciones Total Premios 215 Nominaciones 407 Pendientes Las referencias y notas al pie Madonna es una cantante, compositora y actriz. Nació en Bay City, Michigan, el 16 de agosto de 1958, y creció en Rochester Hills, Michigan, se mudó a Nueva York en 1977 para lanzar su carrera en la danza moderna.[1] Después haber sido miembro de los grupos musicales pop Breakfast Club y Emmy, lanzó su auto-titulado álbum debut, Madonna en 1983 por Sire Records.[2] Recibió la nominación a Mejor artista nuevo en el MTV Video Music Awards (VMA) de 1984 por la canción «Borderline». Madonna fue seguido por una serie de éxitosos sencillos, de sus álbumes de estudio Like a Virgin de 1984 y True Blue en 1986, que le dieron reconocimiento mundial.[3] Madonna, se convirtió en un icono pop, empujando los límites de contenido lírico de la música popular y las imágenes de sus videos musicales, que se convirtió en un fijo en MTV.[4] En 1985, recibió una serie de nominaciones VMA por sus videos musicales y dos nominaciones en a la mejor interpretación vocal pop femenina de los premios Grammy. La revista Billboard la clasificó en lista Top Pop Artist para 1985, así como en el Top Pop Singles Artist en los próximos dos años. -

How Understanding Arrangement Techniques Can Improve Your Songs Mike Levine on Jul 04, 2017 in Music Theory & Education 1 Comments

Arranging for Success - How Understanding Arrangement Techniques Can I : Ask.Au... Page 1 of 6 Arranging for Success - How Understanding Arrangement Techniques Can Improve Your Songs Mike Levine on Jul 04, 2017 in Music Theory & Education 1 comments Understanding some key universal concepts around arrangement, dynamics and composition can help you take your tracks to the next level. Here's how. Whether you’re in the studio or on stage, just having a strong song and performing it well is not enough. You also need a smart arrangement in order for your song to have its maximum impact. Giving your arrangement a dramatic arc helps make it more interesting and accessible to listeners. It's beyond the scope of this article to focus on specific instruments and how to arrange them for particular musical genres—that would require a series of books—but the aim here is to cover some global arranging concepts, which will apply no matter what the specific style or instrumentation. Contrast is King Just like a painting, a song arrangement needs contrast. If everything is too similar, it will be boring and the listeners will tune out. You want to keep their attention, so you should structure the song so that it’s not static. Think of it almost like a book or play, which has a beginning a middle and an end. You have a number of tools at your disposal for creating drama and interest with your arrangement, which include varying the dynamics, adding to the instrumentation as you go, and building the complexity of the instrument and vocal parts as the song progresses. -

Introduction to Music Technology

PUBLIC SCHOOLS OF EDISON TOWNSHIP DIVISION OF CURRICULUM AND INSTRUCTION INTRODUCTION TO MUSIC TECHNOLOGY Length of Course: Semester (Full Year) Elective / Required: Elective Schools: High Schools Student Eligibility: Grade 9-12 Credit Value: 5 credits Date Approved: September 24, 2012 Introduction to Music Technology TABLE OF CONTENTS Statement of Purpose ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 Course Objectives ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Unit 1: Introduction to Music Technology Course and Lab ------------------------------------9 Unit 2: Legal and Ethical Issues In Digital Music -----------------------------------------------11 Unit 3: Basic Projects: Mash-ups and Podcasts ------------------------------------------------13 Unit 4: The Science of Sound & Sound Transmission ----------------------------------------14 Unit 5: Sound Reproduction – From Edison to MP3 ------------------------------------------16 Unit 6: Electronic Composition – Tools For The Musician -----------------------------------18 Unit 7: Pro Tools ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------20 Unit 8: Matching Sight to Sound: Video & Film -------------------------------------------------22 APPENDICES A Performance Assessments B Course Texts and Supplemental Materials C Technology/Website References D Arts -

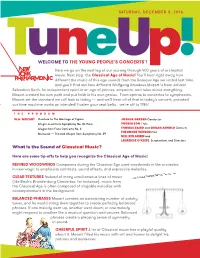

What Is the Sound of Classical Music? WELCOME to THE

Life on Tour in the Classical Age of Music During the 18th century it was fashionable for wealthy young men to finish their education with a grand tour of Europe’s SATURDAY, DECEMBER 3, 2016 cultural capitals. Exposure to art, languages, and artifacts developed young minds and their knowledge of the world. Mozart was just 7 years old when he set off on his first grand tour with his parents and sister, designed as an opportunity to showcase young Wolfgang and sister Nannerl’s talents. What might it be like to go on tour in the 1760s? TRAVEL CHALLENGES The Mozart family traveled about 2,500 miles — In addition to carriage breakdowns, which meant delays for the distance from New York to Los Angeles — in a days while repairs were being made, the cold chill during the cramped, unheated, incredibly bumpy carriage. rides led to lots of illness. Rheumatic fever, tonsillitis, scarlet TM Travels by boat across rivers and the sea were fever, and typhoid fever were experienced by Mozart family WELCOME TO THE YOUNG PEOPLE’S CONCERTS ! equally unpleasant! members, who were bedridden for weeks at a time. TuneUp! Here we go on the next leg of our journey through 400 years of orchestral LODGING HIGHLIGHTS music. Next stop: the Classical Age of Music! You’ll hear right away how The family stayed everywhere from a cramped Wolfgang and Nannerl performed for some of Europe’s most different the music of this age sounds from the Baroque Age we visited last time. three-room apartment above a barber shop to distinguished royalty and at some of the world’s loveliest Buckingham palace! palaces. -

The Relationship Between Music Participation and Mathematics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Liberty University Digital Commons THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MUSIC PARTICIPATION AND MATHEMATICS ACHIEVEMENT IN MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS by Joshua Robert Boyd Liberty University A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Liberty University March, 2013 THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MUSIC PARTICIPATION AND MATHEMATICS ACHIEVEMENT IN MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS by Joshua Robert Boyd A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA March, 2013 APPROVED BY: Dr. Leonard Parker, Ed.D., Committee Chair Dr. Joan Fitzpatrick, Ph.D., Committee Member Dr. Laurie Barron, Ed.D., Committee Member Scott B. Watson, Ph.D., Associate Dean, Advanced Programs ii THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MUSIC PARTICIPATION AND MATHEMATICS ACHIEVEMENT IN MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS ABSTRACT Joshua Boyd. (under the direction of Dr. Leonard W. Parker) School of Education, Liberty University, March, 2013. A comparative analysis was used to study the results from a descriptive survey of selected middle school students in Grades 6, 7, and 8. Student responses to the survey tool was used to compare multiple variables of music participation and duration of various musical activities, such as singing and performing on instruments, to the mathematics results from Georgia Criterion-Referenced Competency Test (Georgia Department of Education, 2011. The results were analyzed with the use of the Pearson r correlation coefficient. The intensity of relationships was assessed with analysis of variance (ANOVA). A final t-test of means was conducted to compare the mathematics achievement of students, who reported that they participated in musical activities vs. -

Music Technology Grade 6

MUSIC TECHNOLOGY GRADE 6 THE EWING PUBLIC SCHOOLS 2099 Pennington Road Ewing, NJ 08618 Revision Date: February 25, 2019__ Michael Nitti Written by: Music Teachers Superintendent In accordance with The Ewing Public Schools’ Policy 2230, Course Guides, this curriculum has been reviewed and found to be in compliance with all policies and all affirmative action criteria. Table of Contents Page Preface 3 21st Century Life and Careers 4 Scope of Essential Learning: Unit 1: Introduction to Music Technology (9 Class Sessions) 5 Unit 2: Acoustics: The Science of Sound (5 Class Sessions) 9 Unit 3: Sound Engineering (12 Class Sessions) 13 Unit 4: The Technology of Music (9 Class Sessions) 16 Unit 5: Final Project Creation (10 Class Sessions) 20 Sample 21st Century, Career, & Technology Integration 23 Preface The purpose of all music courses in The Ewing Public Schools is to develop comprehensive musicianship with a focus on musical literacy. As music educators, we believe all students are musical by nature and have a tremendous potential to learn and enjoy music. While research shows that music helps students to develop higher-order skills and increases desire to learn, our driving goal is to help students become more enlightened and truly alive through a balanced, comprehensive and sequential program of study. The Middle School General Music program allows students to transfer prior knowledge and skills and to explore and develop their musicianship through various units of study. The Music Technology class is a semester-long course offered to 6th graders, every other day for 41 minutes. 3 21st Century Life and Careers In today's global economy, students need to be lifelong learners who have the knowledge and skills to adapt to an evolving workplace and world. -

You Can Judge an Artist by an Album Cover: Using Images for Music Annotation

You Can Judge an Artist by an Album Cover: Using Images for Music Annotation Janis¯ L¯ıbeks Douglas Turnbull Swarthmore College Department of Computer Science Swarthmore, PA 19081 Ithaca College Email: [email protected] Ithaca, NY 14850 Email: [email protected] Abstract—While the perception of music tends to focus on our acoustic listening experience, the image of an artist can play a role in how we categorize (and thus judge) the artistic work. Based on a user study, we show that both album cover artwork and promotional photographs encode valuable information that helps place an artist into a musical context. We also describe a simple computer vision system that can predict music genre tags based on content-based image analysis. This suggests that we can automatically learn some notion of artist similarity based on visual appearance alone. Such visual information may be helpful for improving music discovery in terms of the quality of recommendations, the efficiency of the search process, and the aesthetics of the multimedia experience. Fig. 1. Illustrative promotional photos (left) and album covers (right) of artists with the tags pop (1st row), hip hop (2nd row), metal (3rd row). See I. INTRODUCTION Section VI for attribution. Imagine that you are at a large summer music festival. appearance. Such a measure is useful, for example, because You walk over to one of the side stages and observe a band it allows us to develop a novel music retrieval paradigm in which is about to begin their sound check. Each member of which a user can discover new artists by specifying a query the band has long unkempt hair and is wearing black t-shirts, image. -

Music Technology Strand Anchor Standard 1: Generate and Conceptualize Artistic Ideas and Work

Music - Music Technology Strand Anchor Standard 1: Generate and conceptualize artistic ideas and work. Enduring Understanding: The creative ideas, concepts, and feelings that influence musicians’ work emerge from a variety of sources. Essential Question(s): How do musicians generate creative ideas? HS Proficient HS Accomplished HS Advanced CREATING MU:Cr1.1.T.IIIa Generate melodic, rhythmic, and MU:Cr1.1.T.Ia Generate melodic, rhythmic, and MU:Cr1.1.T.IIa Generate melodic, rhythmic, and harmonic ideas for compositions and harmonic ideas for compositions or improvisations harmonic ideas for compositions and improvisations that incorporate digital tools, Imagine using digital tools. improvisations using digital tools and resources . Imagine resources, and systems . Anchor Standard 2: Organize and develop artistic ideas and work. Enduring Understanding: Musicians’ creative choices are influenced by their expertise, context, and expressive intent. Essential Question(s): How do musicians make creative decisions? HS Proficient HS Accomplished HS Advanced CREATING MU:Cr2.1.T.IIIa Select, develop, and organize MU:Cr2.1.T.IIa Select melodic, rhythmic, and MU:Cr2.1.T.Ia Select melodic, rhythmic, and multiple melodic, rhythmic and harmonic ideas to harmonic ideas to develop into a larger work that harmonic ideas to develop into a larger work using develop into a larger work that exhibits unity, exhibits unity and variety using digital and analog digital tools and resources. variety, complexity, and coherence using digital and tools. Plan andPlan Make analog tools, resources , and systems . andPlan Make Anchor Standard 3: Refine and complete artistic work. Enduring Understanding: Musicians evaluate, and refine their work through openness to new ideas, persistence, and the application of appropriate criteria. -

The Conducting Manual of the Basic Music Course

B A S I C M U S I C C O U R S E CONDUCTING COURSE THE CONDUCTING MANUAL OF THE BASIC MUSIC COURSE Copyright © 1992 The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah 31241 5/92 CONTENTS Introduction to the Basic Music Course......1 Pickup Beats...........................................38 Some Tips on Conducting.........................63 Advice to Students ......................................3 The Cutoff between Verses Interpreting Hymns....................................64 in Hymns with Pickup Beats..................39 Learning about Beats and Rhythm .............4 Sight Singing .............................................65 Fermatas ................................................40 Counting the Beats .....................................6 Cutoff: Review.........................................41 Guidelines for Teachers.............................67 The Time Signature ....................................7 Dotted Notes ..........................................42 How to Set Up Basic Time and Tempo ........................................8 Music Course Programs .......................67 Hymns with Dotted Notes .......................43 The Downbeat.............................................9 In Stakes ..............................................67 The Two-beat Pattern................................44 Notes and Rhythm ....................................10 In Wards ..............................................67