The Loss of Resistance Nerve Blocks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JMSCR Vol||06||Issue||12||Page 318-327||December 2018

JMSCR Vol||06||Issue||12||Page 318-327||December 2018 www.jmscr.igmpublication.org Impact Factor (SJIF): 6.379 Index Copernicus Value: 79.54 ISSN (e)-2347-176x ISSN (p) 2455-0450 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.18535/jmscr/v6i12.50 Routine Ilionguinal and Iliohypogastric Nerve Excision in Lichenstein Hernia Repair - A Prospective Study of 50 Cases Authors Dr Harekrishna Majhi1, Dr Bhupesh Kumar Nayak2 1Associate Professor, Department of General Surgery, VSS IMSAR, Burla 2Senior Resident, Department of General Surgery, VSS IMSAR, Burla Email: [email protected], Contact No.: 9437137230 Abstract Chronic inguinal neuralgia is one of the most significant complications following inguinal hernia repair. Subsequent patient disability can be severe & may often require numerous interventions for treatment. The purpose of the study is to evaluate long term outcomes following nerve excision to nerve preservation when performing lichenstein inguinal hernia repairs. A prospective study of cases with excision of illionguinal & illiohypogastric nerve excision during lichenstein hernia repair with post operative groin repair at 6 month & 1 yrs from May 2015-17 was carried out in the Deptt. of General Surgery, VSSIMSAR, Burla. neuralgia reported for Lichtenstein repair of Introduction inguinal hernias range from 6% to 29%. The No disease of human body, belongs to the probable cause of chronic inguiodynia after province of the surgeon, requires its treatment, a hernioplasty due to entrapment, inflammation, better combination of accurate anatomical ligation, neuroma or fibrotic reactions involving knowledge with surgical skill than hernia in all its ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric & genitial branch of variety. This statement made by SIR Astley genito-femoral nerve. -

Pelvic Anatomyanatomy

PelvicPelvic AnatomyAnatomy RobertRobert E.E. Gutman,Gutman, MDMD ObjectivesObjectives UnderstandUnderstand pelvicpelvic anatomyanatomy Organs and structures of the female pelvis Vascular Supply Neurologic supply Pelvic and retroperitoneal contents and spaces Bony structures Connective tissue (fascia, ligaments) Pelvic floor and abdominal musculature DescribeDescribe functionalfunctional anatomyanatomy andand relevantrelevant pathophysiologypathophysiology Pelvic support Urinary continence Fecal continence AbdominalAbdominal WallWall RectusRectus FasciaFascia LayersLayers WhatWhat areare thethe layerslayers ofof thethe rectusrectus fasciafascia AboveAbove thethe arcuatearcuate line?line? BelowBelow thethe arcuatearcuate line?line? MedianMedial umbilicalumbilical fold Lateralligaments umbilical & folds folds BonyBony AnatomyAnatomy andand LigamentsLigaments BonyBony PelvisPelvis TheThe bonybony pelvispelvis isis comprisedcomprised ofof 22 innominateinnominate bones,bones, thethe sacrum,sacrum, andand thethe coccyx.coccyx. WhatWhat 33 piecespieces fusefuse toto makemake thethe InnominateInnominate bone?bone? PubisPubis IschiumIschium IliumIlium ClinicalClinical PelvimetryPelvimetry WhichWhich measurementsmeasurements thatthat cancan bebe mademade onon exam?exam? InletInlet DiagonalDiagonal ConjugateConjugate MidplaneMidplane InterspinousInterspinous diameterdiameter OutletOutlet TransverseTransverse diameterdiameter ((intertuberousintertuberous)) andand APAP diameterdiameter ((symphysissymphysis toto coccyx)coccyx) -

Administering a Subcutaneous Injection

Inject medication slowly and release skin Will the injection hurt? Children may describe a pinching/stinging or bee-sting sensation during Our Lady’s Children’s Leave needle in place for 5-10 seconds after and just after the injection. It is normal for the Hospital, Crumlin, Dublin injecting medication, if possible injection site to be a little red and tender. It is 12 Remove needle swiftly and smoothly expected that children may be afraid of injections. It is important to be honest and explain the Wipe area gently with cotton wool, do not rub injection in a manner that they can understand. ….where children’s health comes first as this may be sore. Apply a plaster if needed. How to reduce any discomfort: ADVICE FOR • Prepare your child, explain why this is necessary PARENTS/GUARDIANS/CHILDREN and how you will give the injection Step 4. Dispose of the Needle/Syringe • Use distraction and play to amuse your child Administering a • Encourage them to practice on their teddy or doll. For infants, give them a soother/comforter if Subcutaneous Injection Dispose of needle and syringe immediately into they use one a sharps bin • Ensure clothing over the injection site is not tight My child has a bleeding disorder: seek medical advice before giving injections to your child. Auto-injector: Some children use an automatic injection device, often called a ‘rocket’. Specific Instructions: ……………………………………………………………………… ………………………………………………………………………. Developed by: Naomi Bartley, Clinical Placement Coordinator. CONTACT DETAILS Example of an Auto-Injector st Date issued: July 2014, October 2012 : 1 edn. Ward / Dept. Name: _________________ Date of review: July 2017 Telephone: ___________________ Follow the manufacture’s instructions for ©2014, Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital Crumlin, Dublin 12. -

Fascia Iliaca Block in the Emergency Department for Hip Fracture

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Serveur académique lausannois Pasquier et al. BMC Geriatrics (2019) 19:180 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1193-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Fascia iliaca block in the emergency department for hip fracture: a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial Mathieu Pasquier1, Patrick Taffé2, Olivier Hugli1, Olivier Borens3, Kyle Robert Kirkham4 and Eric Albrecht5* Abstract Background: Hip fracture causes moderate to severe pain and while fascia iliaca block has been reported to provide analgesic benefit, most previous trials were unblinded, with subsequent high risks of performance, selection and detection biases. In this randomized, control double-blind trial, we tested the hypothesis that a fascia iliaca block provides effective analgesia for patients suffering from hip fracture. Methods: Thirty ASA I-III hip fracture patients over 70 years old, who received prehospital morphine, were randomized to receive either a fascia iliaca block using 30 ml of bupivacaine 0.5% with epinephrine 1:200,000 or a sham injection with normal saline. The fascia iliaca block was administered by emergency medicine physicians trained to perform an anatomic landmark-based technique. The primary outcome was the comparison between groups of the longitudinal pain score profiles at rest over the first 45 min following the procedure (numeric rating scale, 0–10). Secondary outcomes included the longitudinal pain score profiles on movement and the comparison over 4 h, 8 h, 12 h, and 24 h after the procedure, along with cumulative intravenous morphine consumption at 24 h. Results: At baseline, the fascia iliaca group had a lower mean pain score than the sham injection group, both at rest (difference = − 0.9, 95%CI [− 2.4, 0.5]) and on movement (difference = − 0.9, 95%CI [− 2.7; 0.9]). -

The Spinal Nerves That Constitute the Plexus Lumbosacrales of Porcupines (Hystrix Cristata)

Original Paper Veterinarni Medicina, 54, 2009 (4): 194–197 The spinal nerves that constitute the plexus lumbosacrales of porcupines (Hystrix cristata) A. Aydin, G. Dinc, S. Yilmaz Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Firat University, Elazig, Turkey ABSTRACT: In this study, the spinal nerves that constitute the plexus lumbosacrales of porcupines (Hystrix cristata) were investigated. Four porcupines (two males and two females) were used in this work. Animals were appropriately dissected and the spinal nerves that constitute the plexus lumbosacrales were examined. It was found that the plexus lumbosacrales of the porcupines was formed by whole rami ventralis of L1, L2, L3, L4, S1 and a fine branch from T15 and S2. The rami ventralis of T15 and S2 were divided into two branches. The caudal branch of T15 and cranial branch of S2 contributed to the plexus lumbosacrales. At the last part of the plexus lumbosacrales, a thick branch was formed by contributions from the whole of L4 and S1, and a branch from each of L3 and S2. This root gives rise to the nerve branches which are disseminated to the posterior legs (caudal glu- teal nerve, caudal cutaneous femoral nerve, ischiadic nerve). Thus, the origins of spinal nerves that constitute the plexus lumbosacrales of porcupine differ from rodantia and other mammals. Keywords: lumbosacral plexus; nerves; posterior legs; porcupines (Hystrix cristata) List of abbreviations M = musculus, T = thoracal, L = lumbal, S = sacral, Ca = caudal The porcupine is a member of the Hystricidae fam- were opened by an incision made along the linea ily, a small group of rodentia (Karol, 1963; Weichert, alba and a dissection of the muscles. -

Study of Anatomical Pattern of Lumbar Plexus in Human (Cadaveric Study)

54 Az. J. Pharm Sci. Vol. 54, September, 2016. STUDY OF ANATOMICAL PATTERN OF LUMBAR PLEXUS IN HUMAN (CADAVERIC STUDY) BY Prof. Gamal S Desouki, prof. Maged S Alansary,dr Ahmed K Elbana and Mohammad H Mandor FROM Professor Anatomy and Embryology Faculty of Medicine - Al-Azhar University professor of anesthesia Faculty of Medicine - Al-Azhar University Anatomy and Embryology Faculty of Medicine - Al-Azhar University Department of Anatomy and Embryology Faculty of Medicine of Al-Azhar University, Cairo Abstract The lumbar plexus is situated within the substance of the posterior part of psoas major muscle. It is formed by the ventral rami of the frist three nerves and greater part of the fourth lumbar nerve with or without a contribution from the ventral ramus of last thoracic nerve. The pattern of formation of lumbar plexus is altered if the plexus is prefixed (if the third lumbar is the lowest nerve which enters the lumbar plexus) or postfixed (if there is contribution from the 5th lumbar nerve). The branches of the lumbar plexus may be injured during lumbar plexus block and certain surgical procedures, particularly in the lower abdominal region (appendectomy, inguinal hernia repair, iliac crest bone graft harvesting and gynecologic procedures through transverse incisions). Thus, a better knowledge of the regional anatomy and its variations is essential for preventing the lesions of the branches of the lumbar plexus. Key Words: Anatomical variations, Lumbar plexus. Introduction The lumbar plexus formed by the ventral rami of the upper three nerves and most of the fourth lumbar nerve with or without a contribution from the ventral ramous of last thoracic nerve. -

Technical Considerations for Pen, Jet, and Related Injectors Intended for Use with Drugs and Biological Products

Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff: Technical Considerations for Pen, Jet, and Related Injectors Intended for Use with Drugs and Biological Products Additional copies are available from: Office of Combination Products Office of Special Medical Programs Office of the Commissioner Food and Drug Administration 10903 New Hampshire Avenue, WO-32 Hub 5129 Silver Spring, MD 20993 (Tel) 301-796-8930 (Fax) 301-796-8619 http://www.fda.gov/CombinationProducts/default.htm This document finalizes the draft guidance issued in April 2009. For questions regarding this document, contact the Office of Combination Products at [email protected] or Patricia Y. Love, MD at 301-796-8933 or [email protected] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Center for Drug Evaluation Research, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, and Office of Combination Products in the Office of the Commissioner June 2013 Contains Nonbinding Recommendations Table of Contents INTRODUCTION.....................................................................................................................3 BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................................4 SECTION I: SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS.............................5 A. INJECTOR DESCRIPTION .............................................................................................5 B. DESIGN FEATURES.........................................................................................................9 -

Refi Ning Procedures for the Administration of Substances

WORKINGPARTY REPORT Rening procedures for theadministration of substances Report of the BVAAWF =FRAME=RSPCA=UFAW JointWorking Group on Renement Members of theJoint Working Groupon Renement: D.B.Morton (Chairman), M.Jennings (Secretary),A. Buckwell, R.Ewbank, C.Godfrey, B.Holgate, I. Inglis, R.James, C.Page,I. Sharman, R.Verschoyle, L.Westall &A.B.Wilson Contents Preface 2 3.6 Intraperitoneal 19 1Introduction and aimsof thereport 2 3.7 Intratracheal 20 3.8 Intravaginal 20 2Generalprinc iplesof `good practice’ 3 2.1 Planningand preparation 3 3.9 Intravenous and intra-arterial 21 2.1.1 Experimental aims 3 3.10 Oral routes 25 2.1.2 Theroute 3 3.10.1 Inclusionin an animal’s food orwater 25 2.1.3 Thesubstance 3 3.10.2 Dosingdirectly into 2.1.4 Theanimal 5 the pharynx 27 2.1.5 Thetechnique 7 3.10.3 Oral gavage 28 2.1.6 Staff and training 7 3.11 Osmotic minipumps 30 2.2 Technical preparation 3.12 Respiratory routes 31 andaftercare 8 3.12.1 Wholebody exposure 31 2.3 Generalre® nem entfor 3.12.2 Noseonly =Snout only all routes 9 exposure 32 3Re®nem entfor individual routes 3.12.3 Mask exposure 33 and procedures 13 3.13 Subcutaneous 34 3.1 Intra-articular 13 3.14 TopicalÐderm al 35 3.2 Intracerebral (intracerebro- 3.15 TopicalÐoc ular 36 ventricular) 14 3.16 Footpad 37 3.3 Intradermal 16 3.17 Uncommonroutes 38 3.4 Intramuscular 16 4Special considerations for wildanimals 38 3.5 Intranasal 18 References 39 Correspo ndenceandre q uestsfo rreprintst o:ProfessorD.B.Morton,DepartmentofBiomedicalSciences & BiomedicalEthic s, TheMed icalScho ol,UniversityofBirm ingham,Ed gbaston,Birm inghamB152TT, UK Accepted 14July 2000 # LaboratoryAnimals Ltd. -

Upper and Lower Limb Blocks in Children

Upper and lower limb blocks in children Adrian Bosenberg Correspondence Email: [email protected] INTRODUCTION insulated needles are the next best option Regional anaesthesia is commonly used as an although successful blocks can be achieved with 6 rinciples of clinical anaesthesia adjunct to general anaesthesia and plays a key non-insulated needles. P role in the multimodal approach to perioperative Nerve stimulator 1,2 pain management in children. Peripheral nerve Many peripheral nerve stimulators are available. SUMMARY blockade has increased with the development of Familiarise yourself with a particular device and age-appropriate equipment, safer, long-acting This article outlines regional stick with it. Read the manufacturer’s instructions anaesthetic techniques and local anaesthetic agents, increasing experience and understand how the nerve stimulator works methods used to identify and and low complication rates. before you use it.7 block individual nerves to provide analgesia for surgical The safety of peripheral nerve blocks in children The following basic principles should be followed procedures of the upper has been established in large-scale prospective to locate a peripheral nerve or plexus accurately: and lower limbs. Expertly studies, although caudal epidural remains the performed, peripheral nerve most popular and frequently used block in • Muscle relaxants must be withheld until after blocks can provide long lasting 3-5 completion of the block. anaesthesia and analgesia infants and small children. The experience of for surgery or after injury to the operator, pathology, the site and extent of • Attach the Negative electrode to the Needle the upper or lower limbs in surgery, the child’s body habitus and the presence and the Positive electrode to the Patient using children. -

Posterior Approach to Kidney Dissection: an Old Surgical Approach for Integrated Medical Curricula Frank J

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of New England University of New England DUNE: DigitalUNE Biomedical Sciences Faculty Publications Biomedical Sciences Faculty Works 2-16-2015 Posterior Approach To Kidney Dissection: An Old Surgical Approach For Integrated Medical Curricula Frank J. Daly University of New England, [email protected] David L. Bolender Medical College of Wisconsin Deepali Jain Michigan State University Sheryl Uyeda SUNY Upstate Medical University Todd M. Hoagland Medical College of Wisconsin Follow this and additional works at: http://dune.une.edu/biomed_facpubs Part of the Endocrine System Commons, and the Urogenital System Commons Recommended Citation Daly, Frank J.; Bolender, David L.; Jain, Deepali; Uyeda, Sheryl; and Hoagland, Todd M., "Posterior Approach To Kidney Dissection: An Old Surgical Approach For Integrated Medical Curricula" (2015). Biomedical Sciences Faculty Publications. 6. http://dune.une.edu/biomed_facpubs/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biomedical Sciences Faculty Works at DUNE: DigitalUNE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biomedical Sciences Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DUNE: DigitalUNE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Posterior Approach to Kidney Dissection 1 ASE-14-0094.R1 Descriptive article Posterior Approach to Kidney Dissection: An Old Surgical Approach for Integrated Medical Curricula Frank J. Daly1*, David L. Bolender2, Deepali Jain3, Sheryl Uyeda4, Todd M. Hoagland2 1Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine, Biddeford, Maine 2Department of Cell Biology, Neurobiology and Anatomy, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 3Department of Surgery, Grand Rapids Educational Partners, Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, Grand Rapids, Michigan. -

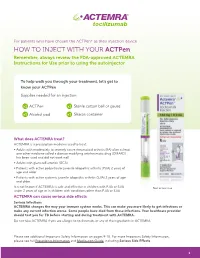

HOW to INJECT with YOUR Actpen Remember, Always Review the FDA-Approved ACTEMRA Instructions for Use Prior to Using the Autoinjector

For patients who have chosen the ACTPen® as their injection device HOW TO INJECT WITH YOUR ACTPen Remember, always review the FDA-approved ACTEMRA Instructions for Use prior to using the autoinjector To help walk you through your treatment, let’s get to know your ACTPen Supplies needed for an injection: x1 ACTPen x1 Sterile cotton ball or gauze x1 Alcohol pad x1 Sharps container What does ACTEMRA treat? ACTEMRA is a prescription medicine used to treat: • Adults with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis (RA) after at least one other medicine called a disease modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) has been used and did not work well • Adults with giant cell arteritis (GCA) • Patients with active polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (PJIA) 2 years of age and older • Patients with active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SJIA) 2 years of age and older It is not known if ACTEMRA is safe and effective in children with PJIA or SJIA Not actual size. under 2 years of age or in children with conditions other than PJIA or SJIA. ACTEMRA can cause serious side effects Serious Infections ACTEMRA changes the way your immune system works. This can make you more likely to get infections or make any current infection worse. Some people have died from these infections. Your healthcare provider should test you for TB before starting and during treatment with ACTEMRA. Do not take ACTEMRA if you are allergic to tocilizumab, or any of the ingredients in ACTEMRA. Please see additional Important Safety Information on pages 9-10. For more Important Safety Information, please see full Prescribing Information and Medication Guide, including Serious Side Effects. -

Injectable Supramolecular Polymer–Nanoparticle Hydrogels Enhance Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Delivery

Received: 13 July 2019 Revised: 25 September 2019 Accepted: 1 October 2019 DOI: 10.1002/btm2.10147 RESEARCH REPORT Injectable supramolecular polymer–nanoparticle hydrogels enhance human mesenchymal stem cell delivery Abigail K. Grosskopf1 | Gillie A. Roth2 | Anton A. A. Smith3 | Emily C. Gale4 | Hector Lopez Hernandez3 | Eric A. Appel3 1Department of Chemical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, California Abstract 2Department of Bioengineering, Stanford Stem cell therapies have emerged as promising treatments for injuries and diseases in University, Stanford, California regenerative medicine. Yet, delivering stem cells therapeutically can be complicated 3Department of Materials Science & Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, by invasive administration techniques, heterogeneity in the injection media, and/or California poor cell retention at the injection site. Despite these issues, traditional administra- 4 Department of Biochemistry, Stanford tion protocols using bolus injections in a saline solution or surgical implants of cell- University, Stanford, California laden hydrogels have highlighted the promise of cell administration as a treatment Correspondence strategy. To address these limitations, we have designed an injectable polymer– Eric A. Appel, Department of Materials Science & Engineering, Stanford University, nanoparticle (PNP) hydrogel platform exploiting multivalent, noncovalent interactions Stanford, CA 94305. between modified biopolymers and biodegradable nanoparticles for encapsulation Email: [email protected]