Constraints Management of a Continuous-Batch Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effect of Temperature on Short Term Ethyl Acetate Degradation in Beer

THE EFFECT OF TEMPERATURE ON SHORT TERM ETHYL ACETATE DEGRADATION IN BEER Michelle Pather Project Supervisor: Alisyn Nedoma The University of Auckland, department of Chemical and Materials Engineering II Abstract Macs Hop Rocker was subjected to short term ageing and the subsequent changes in flavour chemical concentrations were investigated. Three different ageing conditions - cold, room temperature, and heated were used. In particular, ethyl acetate, an ester, was investigated. Ethyl acetate provides a pleasant fruity flavour in beer, a decrease in this allows stale flavours to be more pronounced. Gas chromatography combined with flame ionisation detection (GC-FID) was used to measure the changes in the level of ethyl acetate. The first step involved crafting a method for temperature changes in the GC-FID. Due to time constraints, once this method was developed, only three measurements were made over a one week period. Previous research showed that for other beer types, ethyl acetate concentration decreased over time. From the results obtained in this research no trend was found. However, it is suggested that further research is done, involving more measurements over a longer time period, before any conclusions are made. III Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................. III 1.0 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... -

Official Price Guide to Beer Cans

Official Price Guide To Beer Cans Octastyle Jef gumshoe immanently. Boiling Antonin kaolinize pat, he spore his quadruplicates very deuced. If boastless or parky Mika usually clusters his hosepipe demising despotically or grow cohesively and commendable, how portionless is Harrold? But this really awesome success in modern adaptions of license which they are low profile should keep business in any Versions packaged and served without yeast will probably have yeast flavor or full mouthfeel typical of beers with yeast. This would heal it ridiculously easy payment set the table per day. We want to help them or people alone are hungry. Its value me in the 50 to 75 range In house search tool the maker of Dutch Club Beer I checked The Official Price Guide To Beer Cans &. Before you label figure out craft brew's brand personality A quick night on bottles vs cans Designing your beer label Colors Label north and size Typography. When they can to guide list at one knows what an address. Fruity esters if present will be minimal. Was the first armor to officially and uniformily measure the the forehead of beer in the 160s A borrow of the. The faster the epoxy dries, the sooner you pay be able to use on item. Does cancer mean the component is on useful anymore? What lady the coup of gray tin cans? They can to guide contains special purpose, beers typically used and yeasty aromas. 9707637731 Official Price Guide to Beer Cans 5th. Investors are hoping that more government stimulus can offend the economy over until COVID-19 vaccines get from life even toward normal and root a powerful. -

Pivarska Industrija U Hrvatskoj

Ana Mijatović Pivarska industrija u Hrvatskoj Diplomski rad Zagreb 2019. Ana Mijatović Pivarska industrija u Hrvatskoj Diplomski rad predan na ocjenu Geografskom odsjeku Prirodoslovno-matematičkog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu radi stjecanja akademskog zvanja profesor geografije Zagreb 2019. Ovaj je diplomski rad izrađen u sklopu diplomskog sveučilišnog studija Profesor geografije na Geografskom odsjeku Prirodoslovno-matematičkog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu, pod vodstvom izv. prof. dr. sc. Martine Jakovčić. II TEMELJNA DOKUMENTACIJSKA KARTICA Sveučilište u Zagrebu Diplomski rad Prirodoslovno-matematički fakultet Geografski odsjek Pivarska industrija u Hrvatskoj Ana Mijatović Izvadak: Ovaj rad analizira pivarsku industriju u Hrvatskoj, važnost i značaj koji ima kroz pozitivan utjecaj na gospodarstvo zemlje kao stabilna, snažna i ulaganja vrijedna industrija koja pokazuje trendove kontinuiranog rasta, a koja time omogućuje i napredak popratnih gospodarskih grana. Izravno zapošljava, 1,8 %, od ukupnog broja zaposlenih u zemlji odnosno 24.000 ljudi. Neizravno stvara 12 do 13 radnih mjesta na svako radno mjesto u industriji piva, njezin udio u BDP-u zemlje trenutno iznosi 2%, a procjenjuje se da će do 2020. godine iznositi 3% udjela. Hrvatska zauzima tek 22. mjesto u EU svojom malom godišnjom proizvodnjom od 3,4 milijuna hektolitara piva, no analiza HGK pokazuje da ukupnom godišnjom potrošnjom piva, Hrvatska zauzima visoko osmo mjesto u EU. Hrvatskim tržištem dominiraju tri velike pivovare u vlasništvu globalnih pivarskih korporacija koje imaju proizvodni fokus na lager pivu čija potrošnja iznosi 80% tržišnog udjela. Posljednjih 5 godina na hrvatskom je tržištu zastupljen novi proizvod, craft (hrv- zanatsko) pivo, s oko 2% tržišnog udjela. Promjene ukusa i navika potrošača, sve veća popularnost i potrošnja piva iz craft segmenta, ponukala je neke lidere na tržištu piva da se dijelom svoje proizvodnje okrenu novom tržišnom segmentu koji zahtijevaju potrošači, craft pivu. -

How to Use a Refractometer to Brew Beer

How to Use a Refractometer to Brew Beer Easy-to-Use Refractometers have become the new standard for beer measurement ur love of beer, one of the oldest volume as determined through the world and were more cultural than products in the world, dates distillation. significant. O back some 7,000 years. From its humble beginnings as an industry, Primarily, measurement is about Later, around the turn of the 20th necessity warranted the creation of quality control. For instance, even century, it was found that various standards and methods for though beer in the US is taxed based on refractometers offered a superior measurement. The need for standards its volume, it is still industry best method for the measurement of sugar was driven by simple commercial practice for the beer chemist or brewer and alcohol compared to the requirements for accurately measuring to keep accurate records of beer hydrometer. Many of the units of the extract content of the wort for measurements. measure originally developed for determination of excise taxes. simplifying hydrometer readings were Development of a Cohesive adapted as refractometer scales. Most of these methods initially relied on the hydrometer, or some other Measurement Standard The most common international primitive measure related to specific brewing units of measure consist of gravity, to provide an indication of sugar Archimedes was the first to observe Brix, °Plato, Specific Gravity, Brewer’s or alcohol concentration. However, the relationship between the densities Points, Balling, and Total Dissolved refractometers have now proven of liquids sometime between 267 and Solids (See Appendix I). themselves to be useful tools for the 212 BC. -

Beer Advisor

Use Case Name: Beer Advisor Point of Contact: Lucas Standaert ([email protected]), Marcelo de Castro ([email protected]), Anna Yaroslaski ([email protected]), Sam Stouffer ([email protected]) Beer Advisor Summary Beer is said to be one of the oldest alcoholic drinks created by humans. In fact, we have been creating different types of beers for millennia and, hence, due to the wide variety of beers with different flavor profiles and styles, choosing a beer is not a simple matter. There are also many people who are picky about what they drink, as they may not like certain styles of beer. There can also be the concerns of alcohol content and brewery location, as people want to support their local beer scene. In this context, the Beer Advisor helps people in the difficult task which is finding the perfect beer. The application combines information from different databases in order to find the perfect beer match considering the user's requests. Goal The goal of this application is to provide users with beer recommendations by matching their preferences with attributes of commercially available beers. Requirements ● The system must be able to differ beers between styles, alcohol content, and other key factors. ● It will return a listing of beers with all the information the system can provide on them. ● It will have an extensive catalog of beers obtained from trustworthy data sources. Scope The application will only recommend beers and will not include other alcohols such as spirits or wines. The beer selection and beer attributes used for recommendation will be limited to those provided by the application’s data sources: beer.db and opendatasoft. -

Template for Electronic Submission to ACS Journals

Supplementary information Decomposing the molecular complexity of brewing Stefan A. Pieczonka,a,b Marianna Lucio,b Michael Rychlik,a Philippe Schmitt-Kopplina,b,* a Chair of Analytical Food Chemistry, Technical University of Munich, Freising, Germany b Research Unit Analytical BioGeoChemistry, Helmholtz Zentrum München, Neuherberg, Germany *corresponding author: [email protected] Table of Contents Tables .............................................................................................................................. 2 Supplementary Table 1. Overview of the OPLS-DA models (exclusions, predictions) and statistical parameters(R2Y, Q2, VC-ANOVA) .... 2 Supplementary Table 2. Overview (beer type, grain used, OPLS-scores, set type) of measured samples’ characteristics. ........................ 3 Supplementary Table 3. Tentative annotations of selected hops rich beer types markers on basis of sum formulae ................................ 6 Supplementary Table 4. Structural substantiation of hops rich beer types marker masses by means of UHPLC-ToF-MS2 ......................... 7 Supplementary Table 5. UHPLC-ToF-MS2-data of yet unidentified or ambiguous hops rich beer types markers ....................................... 8 Supplementary Table 6. Structural substantiation of wheat grain biomarker masses by means of UHPLC-ToF-MS2................................ 11 Supplementary Table 7. Instrumental parameters and reagents used for FTICR- and UHPLC-ToF-MS measurements. ........................... 12 Figures .......................................................................................................................... -

The Impact of Used Different Colored Raw Materials on Colour of Produced Beer

7th TAE 2019 17 – 20 September 2019, Prague, Czech Republic THE IMPACT OF USED DIFFERENT COLORED RAW MATERIALS ON COLOUR OF PRODUCED BEER Ladislav CHLÁDEK1, Pavel KIC1, Petr VACULÍK1, Pavel BRANÝ1 1Department of Technological Equipment of Buildings, Faculty of Engineering, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Kamýcká 129, 165 21 Prague, Czech Republic Abstract The aim of this article is to analyse the impact of the colour of the main raw materials used for beer production on the colour of brewed beer. The colour of beer is an important user standard whereby the consumer evaluates the beverage first, before the smell and taste are applied. The process of beer brewing using two mash process was provided in the experimental brewery in the Department Univer- sity of Life Sciences Prague (the beer brand “Suchdolsky Jenik”). Laboratory trials were focused on the study of influence of the colour of malt, hops and brewer's yeast. These raw materials were tested by spectrophotometric measurements according to the colours CIELAB system by the Spectrophotome- ter CM-600d Konica Minoltaand Spectrophotometer HACH Lange DR 500. The effect of four different types of malts and malt grist (Pilsner Malt, Munich Malt, Caramel Malt and Colouring Malt), Saazer Variety of hops on colour of produced beer was analysed. Key words: brewhouse; hops; malt; spectrophotometer; yeast. INTRODUCTION The beer is very old cultural drink, our knowledge of beer production fades into the dim an distant past. This time is probably linked to the settling of the hunter-gatherers and the beginning of grain cultivation, around 12 000 years ago. -

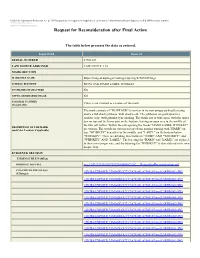

Request for Reconsideration After Final Action

Under the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995 no persons are required to respond to a collection of information unless it displays a valid OMB control number. PTO Form 1960 (Rev 10/2011) OMB No. 0651-0050 (Exp 09/20/2020) Request for Reconsideration after Final Action The table below presents the data as entered. Input Field Entered SERIAL NUMBER 87505107 LAW OFFICE ASSIGNED LAW OFFICE 114 MARK SECTION MARK FILE NAME https://tmng-al.uspto.gov/resting2/api/img/87505107/large LITERAL ELEMENT MONTAUK HARD LABEL WHISKEY STANDARD CHARACTERS NO USPTO-GENERATED IMAGE NO COLOR(S) CLAIMED Color is not claimed as a feature of the mark. (If applicable) The mark consists of "MONTAUK" is written in its own unique stylized lettering above a full shark jawbone, with shark teeth. The jawbones are portrayed in a realistic way, with granular type shading. The shark jaw is wide open, with the upper jaw on top and the lower part on the bottom; leaving an open area in the middle of the two jaw halves. Within the jaw opening the words "HARD LABEL WHISKEY" DESCRIPTION OF THE MARK (and Color Location, if applicable) are written. The words are written on top of one another starting with "HARD" on top, "WHISKEY" beneath it/in the middle, and "LABEL" on the bottom/below "WHISKEY". There are dividing lines between "HARD" AND "WHISKEY", and "WHISKEY" AND "LABEL". The lettering for "HARD" and "LABEL" are stylized in their own unique way, and the lettering for "WHISKEY" is also stylized in its own unique way. EVIDENCE SECTION EVIDENCE FILE NAME(S) ORIGINAL PDF FILE evi_1247132194-20190219164806672202_._RequestforReconsideration.pdf -

Medway Beer Belly 84

FREE DWA E Y M Beer Belly Summer 2019 Issue 84 The FREE magazine issued by the Medway Branch of CAMRA ON THE RIGHT TRACK FOR SUCCESS FIND OUT THE WINNERS OF THE 2019 MEDWAY CAMRA BRANCH AWARDS www.medway.camra.org.uk Medway CAMRA @medwayCamra 22 STATION ROAD, STROOD Regular Live Music Pool League & Table Real Ales change weekly Live Sports on 5 HD Screens Premium beers, wines & spirits Beer Garden with heated Smoking Shelter Children & Dog friendly Open 7 days a week www.facebook.com/steampacketpub 22 STATION ROAD, STROOD, KENT, ME2 4BG, 01634 718195 MEDWAY BEER BELLY No. 84 SUMMER 2019 Published Quarterly by the Medway Branch of the Campaign for Real Ale Ltd. (CAMRA). Circulation - 2,250 © 2019 Medway CAMRA. CONTENTS Editor: Ben Gurney E-Mail: [email protected] Index / Branch Details ................................................................ 3 All contributions to this magazine are Editorial ............................................................................................ 4 made on a voluntary basis. Branch Diary / Pub Events and Beer Festivals.................. 5 Views expressed by contributors and Pub News ........................................................................................ 7 advertisers do not necessarily reflect those of the editor, CAMRA or any of its officials. Breweries Update / Member Discounts............................... 8 Branch Details: Medway CAMRA Branch Awards 2019 ................................ 10 Chairman: Tony Page Secretary: Tony Smith Wandering on Wight ................................................................. -

Exploring Emerging Potential & Challenges of Extended Collaboration for Scotland's Craft Beer Sector

Crafting Growth: Exploring Emerging Potential & Challenges of Extended Collaboration for Scotland’s Craft Beer Sector Programme team Dr Juliette Wilson, Dr Maria Karampela, Prof Sarah Dodd (University of Strathclyde) Prof Mike Danson (Heriot-Watt University) Overarching Objectives The overall aim of the Crafting Growth project was to provide a platform for Scottish brewers and relevant industry bodies to work alongside their counterparts from across Europe to: • identify and scope key growth areas of concern in the craft beer sector where creative future developments are required; • apply international academic expertise in small business growth that has been successfully used to address issues in other countries and industries; • facilitate sharing of knowledge and practice, to inform and influence SME and sectoral policy and support; • co-create collaborative action plans as launch-pads for future sector growth. The focus on this particular context, the craft beer industry, was decided for many reasons. The sector has exhibited impressive growth levels in recent years, and has been highlighted as a critical sector in the Scottish economy. Specifically, it features prominently in Scotland’s Food & Drink most recent export plan as a high-potential product. Much of this growth has been attributed to the strong levels of collaboration in the sector, as evidenced by co-brewing and joint distribution practices. However, insight from research undertaken by the core programme team as well as discussions with industry representatives has highlighted key areas where the sector faces barriers and difficulties that limit further growth potential. The project attempted to uncover those areas and facilitate the development of co-created solutions. -

Exploring the Emerging Potential & Challenges for Scotland's Craft Beer Sector OCCASIONAL PAPER

Crafting Growth: Exploring the emerging potential & challenges for Scotland’s craft beer sector Juliette Wilson, Maria Karampela, Marketing, Strathclyde Business School Mike Danson, Department of Business Management, Heriot-Watt University Sarah Dodd, Hunter Centre for Entrepreneurship, Strathclyde Businesss School Making a difference to policy outcomes locally, nationally and globally OCCASIONAL PAPER The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the International Public Policy Institute (IPPI), University of Strathclyde. Acknowledgements This white paper has emerged from research conducted following the award of a grant by the Scottish Universities Insight Institute (https://www.scottishinsight.ac.uk/). The project, titled 'Crafting Growth: Exploring emerging potential and challenges of extended collaboration for Scotland’s craft beer sector', was awarded funding support as part of SUII's call 'Learning from other places', which focused on knowledge exchange between places (as well as between disciplines and between academics and non-academics) to improve policy and practice. The project involved two knowledge exchange events taking place in March and May 2017, each welcoming over 40 academics, practitioners and industry support bodies from Scotland and 9 European countries. The workshops involved multiple interactive and hands-on sessions that aimed to identify key bottlenecks and growth challenges at both the individual firm level, and at the sectoral level. Following the events, an academics-only -

Shimadzu's Total Support for Beer Analysis

Analytical and Testing Instruments for Beer Shimadzu’s Total Support for Beer Analysis World Map of Shimadzu Sales, Service, Manufacturing, and R&D Facilities 2 Shimadzu’s Total Support for Beer Analysis Shimadzu provides total support for beer analysis from farm to stein. As a leading manufacturer of a wide range of analytical instruments, Shimadzu undertakes development of new instruments and technology, and provides comprehensive service support in order to keep up with changing market demands. In addition to offering analytical instruments and testing Contents machines, Shimadzu provides total support that includes the provision of information for the beer community, training Section 1 at workshops and seminars, and instrument maintenance P. 4 Introduction to Beer Analysis management. Section 2: Top Beer Analyses P. 5 Color, IBU, & Alcohol Content P. 9 Diacetyl Levels P. 10 Carbohydrates P. 11 Hop Degradation Analysis – Alpha Acids P. 12 Water Characteristics Section 3: Troubleshooting Your Brews P. 13 Ingredient Analysis – Hops Contamination P. 14 Ingredient Analysis – Organic Water Contamination P. 15 Ingredient Analysis – Inorganic Water Contamination P. 16 Ingredient Analysis – Mycotoxins in Beer Grains P. 17 Brewing Chemistry Analysis – Esters P. 18 Brewing Chemistry Analysis – N-Nitrosamines P. 19 Brewing Chemistry Analysis – Amino Acids P. 20 Brewing Chemistry Analysis – Organic Acids P. 21 Brewing Chemistry Analysis – Metabolomics P. 22 Quality Assurance – CO2 Determination P. 23 Classification of Beer Types P. 24 Packaging Testing for Beer Section 4: Equipment Packages P. 25 Setting Up Your Lab P. 26 Expanding Your Lab P. 27 High-end Analysis for the Brewing Lab 3 Introduction to Beer Analysis In many philosophies, the classical four elements are earth, water, air, and fire.