The Public Value Notion in UK Public Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Future for Local and Regional Media

House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee Future for local and regional media Fourth Report of Session 2009–10 Volume II Oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 24 March 2010 HC 43-II (Incorporating HC 699-i-iv of Session 2008-09) Published on 6 April 2010 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Culture, Media and Sport Committee The Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mr John Whittingdale MP (Conservative, Maldon and East Chelmsford) (Chair) Mr Peter Ainsworth MP (Conservative, East Surrey) Janet Anderson MP (Labour, Rossendale and Darwen) Mr Philip Davies MP (Conservative, Shipley) Paul Farrelly MP (Labour, Newcastle-under-Lyme) Mr Mike Hall MP (Labour, Weaver Vale) Alan Keen MP (Labour, Feltham and Heston) Rosemary McKenna MP (Labour, Cumbernauld, Kilsyth and Kirkintilloch East) Adam Price MP (Plaid Cymru, Carmarthen East and Dinefwr) Mr Adrian Sanders MP (Liberal Democrat, Torbay) Mr Tom Watson MP (Labour, West Bromwich East) The following members were also members of the committee during the inquiry: Mr Nigel Evans MP (Conservative, Ribble Valley) Helen Southworth MP (Labour, Warrington South) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. -

One Man's Personal Campaign to Save the Building – Page 8

The newspaper for BBC pensioners – with highlights from Ariel online Goodbye TVC One man’s personal campaign to save the building – page 8 April 2013 • Issue 2 bbC expenses regional dance band down television drama memories Page 2 Page 6 Page 7 NEWS • MEMoriES • ClaSSifiEdS • Your lEttErS • obituariES • CroSPEro 02 baCk at thE bbC Pollard Review findings On 22 February, acting director general Tim Davie sent the following email to all staff, in advance of the publication of the Nick Pollard. Pollard Review evidence: hen the Pollard Review was made clearer to ensure all entries meet BBC published back in December, Editorial standards. we said that we would The additional papers we’ve published Club gives tVC a great release all the evidence that today don’t add to Nick Pollard’s findings, send off WNick Pollard provided to us when he they explain the factual basis of how he (where a genuine and identifiable interest of delivered his report. Today we are publishing arrived at them. We’ve already accepted the BBC is at stake). Thank you to all the retired members and all the emails and documents that were the review in full and today’s publication There will inevitably be press interest and ex-staff who joined us for our ‘Goodbye to appended to the report together with the gives us no reason to revisit that decision as you would expect we’re offering support to TVC’ on 9 March. The day started with a transcripts of interviews given to the review. or the actions we are already taking. -

Select Committee of Tynwald on the Television Licence Fee Report 2010/11

PP108/11 SELECT COMMITTEE OF TYNWALD ON THE TELEVISION LICENCE FEE REPORT 2010/11 REPORT OF THE SELECT COMMITTEE OF TYNWALD ON THE TELEVISION LICENCE FEE At the sitting of Tynwald Court on 18th November 2009 it was resolved - "That Tynwald appoints a Committee of three Members with powers to take written and oral evidence pursuant to sections 3 and 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1876, as amended, to investigate the feasibility and impact of withdrawal from or amendment of the agreement under which residents of the Isle of Man pay a television licence fee; and to report." The powers, privileges and immunities relating to the work of a committee of Tynwald are those conferred by sections 3 and 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1876, sections 1 to 4 of the Privileges of Tynwald (Publications) Act 1973 and sections 2 to 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1984. Mr G D Cregeen MHK (Malew & Santon) (Chairman) Mr D A Callister MLC Hon P A Gawne MHK (Rushen) Copies of this Report may be obtained from the Tynwald Library, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas IM7 3PW (Tel 07624 685520, Fax 01624 685522) or may be consulted at www, ,tynwald.orgim All correspondence with regard to this Report should be addressed to the Clerk of Tynwald, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas IMI 3PW TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1 2. The broadcasting landscape in the Isle of Man 4 Historical background 4 Legal framework 5 The requirement to pay the licence fee 5 Whether the licence fee is a UK tax 6 Licence fee collection and enforcement 7 Infrastructure for terrestrial broadcasting 10 Television 10 Radio: limitations of analogue transmission capability and extent of DAB coverage 13 3. -

BBC Trust: Local Video Public Value Assessment

Local0B Video Public1B Value Assessment Organisation Responses November 2008 Introduction The BBC Trust is currently conducting a Public Value Test (PVT) into the proposal for Local Video. As part of the PVT process the BBC Trust must examine the public value of the proposal. As part of the Public Value Assessment (PVA) the trust consulted publicly for 42 days. This document contains the full responses from organisations to the consultation. 1 Organisation responses in full The BBC Trust received representations during the public consultation from the following organisations: Audience Council Northern Ireland Audience Council Wales Barnsley Chronicle BECTU Chris Cherry CN Group Community Media Association Guardian Media Group plc Institute of Welsh Affairs Johnston Press John Rossetti Manx Radio Mediatrust MG Alba Newspaper Society Northcliffe Media NWN Media Ltd PACT RadioCentre Scottish Daily Newspaper Society Scottish Screen Voice of the Listener and the Viewer Five organisations also responded requesting that their submissions remain confidential. 2 Audience Council Northern Ireland AUDIENCE COUNCIL FOR NORTHERN IRELAND (ACNI) INITIAL RESPONSE TO THE BBC TRUST’S PUBLIC VALUE TEST ON THE BBC’S PROPOSAL FOR LOCAL VIDEO 4 AUGUST 2008 The Audience Council for Northern Ireland (ACNI) welcomes the BBC’s proposals for an expansion and enhancement of its on-demand service provision with Local Video. Council sees Local Video as an enhancement to existing services and additional to plans already in place to improve BBC local service provision [specifically those to bring service provision in Northern Ireland (and Scotland) into line with those in England and Wales]. Council also recognises the potential benefits of more user-generated content, giving communities the opportunity for involvement, with BBC support, in generating local news stories. -

Audience Council Review/ Scotland 01/ BBC Trustee for Scotland

2008/09 AUDIENCE COUNCIL REVIEW/ Scotland 01/ BBC TRUstEE FOR SCOTLAND 02/ THE WORK OF THE COUNCIL 07/ BBC PERFORMANCE AGAINst PRIORITIES SET FOR 2008/09 09/ BBC PERFORMANCE AGAINst Its PUBLIC PURPOSES 1 4 / AUDIENCE COUNCIL FOR SCOTLAND PRIORITIES FOR 2009/10 B BBC TRUSTEE FOR ScOTLAND The BBC Audience Councils advise the BBC Trust on how well the BBC is delivering its public purposes and serving licence fee payers across the United Kingdom. The four Councils – serving Scotland, Northern Ireland, England and Wales – are supported by the Trust to provide an independent assessment of audience expectations and issues. A strong year for the BBC in Scotland saw the launch of BBC ALBA (in partnership with MG Alba), a pledge to make more network television in Scotland, and some improvement in network news about the devolved nations. Programme highlights included coverage of the economic crisis, and the multimedia Scotland’s History. We consulted audiences, advising the Trust accordingly. Key issues included the BBC’s plans to improve local coverage, and the debate on the future of public service broadcasting. Audiences in Scotland tell us they want more content reflecting their interests and concerns, while retaining the strengths of the BBC networks. Jeremy Peat National Trustee for Scotland 01 THE WORK OF THE COUNciL Council reflects audience concerns to the BBC. “ We held consultative events with young people, people with disabilities, and members of ethnic and cultural groups.” 02 “Following the debate on public trust in broadcasters, we stressed that the BBC’s customary high standards should be strictly maintained in the future.” Event in Annan. -

DEP2009-0172.Pdf

Contents Section Page 0 One page overview 1 1 Executive summary 2 2 The story so far 14 3 What audiences think about public service content 20 4 Challenge and change 30 5 Maximising value in any future model 44 6 A new approach to public service content 57 7 Ensuring strong public service providers 62 8 Freeing up commercially owned networks 72 9 Future models in the devolved nations and English regions 85 10 Future models for the localities 100 11 Priorities for children’s programming 108 12 Detailed recommendations and next steps 112 Annex Page 1 Glossary 120 Ofcom’s Second Public Service Broadcasting Review: Putting Viewers First Foreword 0 One page overview In this review we have focused on how to ensure the delivery of content which fulfils public purposes and meets the interests of citizens and consumers throughout the UK. Our aim has been to make recommendations that respond to the huge changes brought about by the transition to the digital era. The central question is how a historically strong and successful public service broadcasting system can navigate from its analogue form to a new digital model. We need to sustain its quality and creative spirit while also capturing the opportunities of broadband distribution, mobility and interactivity. Our recommendations are based on detailed audience research, a wide range of views from stakeholders within industry and our own analysis. The recommendations we present to government and Parliament set out what we believe is required to fulfil a vision of diverse, vibrant and engaging public service content enjoyed across a range of digital media, which complements a flourishing and expansive market sector. -

Ripe 2019: Universalism in Public Service Media

UNIVERSALISM IN PUBLIC SERVICE MEDIA RIPE 2019 Edited by: Philip Savage, Mercedes Medina, & Gregory Ferrell Lowe Ferrell Lowe, G. & Savage, P. (2020). Universalism in public service media: Paradoxes, challenges, and development in Philip Savage, Mercedes Medina and Gregory Ferrell Lowe (eds.) Universalism in Public Service Media. Gteborg: Nordicom. NORDICOM 1 Logotyp Logotyp Nordicoms huvudlogotyp består av namnet Nordicoms huvudlogotyp består av namnet ”Nordicom”. Logotypen är det enskilt viktigaste ”Nordicom”. Logotypen är det enskilt viktigaste elementet i Nordicoms visuella identitet och den Centrum fr nordisk medieforskning Centrum fr nordisk medieforskning ska finnas med i allt material där Nordicom står som avsändare. Använd alltid godkända original, de kan laddas ner här. Logotypens tre versioner Nordicoms logotyp finns i tre godkända grundversioner. • Logotyp. • Logotyp med undertext. • Logotyp på platta. Centre for Nordic Media Research Centre for Nordic Media Research Logotyp med undertext ska användas i lite större Logotyp med undertext ska användas i lite större format för att presentera Nordicom. Logotyp format för att presenteraBased at the Nordicom. University of Gothenburg,Logotyp Nordicom is a Nordic non-proft knowledge Contacts på platta ska användas där det behövs något centre that collects and communicates facts and research in the feld of media and communication. The purpose of our work is to develop the knowledge of media’s role Editor Administration, sales Postal address grafiskt med mer tyngd. in society. We do this through: Johannes Bjerling, PhD Anne Claesson Nordicom phone: +46 766 18 12 39 phone: +46 31 786 12 16 University of Gothenburg Following and documenting media development in terms of media structure, • [email protected] [email protected] PO Box 713 media ownership, media economy, and media use. -

Photographing a Revolution Weeks in BBC Maida Vale Studios, London

The newspaper for retired BBC Pension Scheme members • June 2019 • Issue 3 PROSPERO PHOTOGRAPHING A PENSION REVOLUTION SCHEME PAGE 6 | PENSIONS Prospero – your feedback is wanted As part of its periodic review of services and providers, the BBC Pension Trustee will be turning its attention to Grace Wyndham Prospero – not to restrict its availability, but to see how it can continue to evolve to meet the needs of all those receiving a pension from the Scheme. Goldie (BBC) Trust We would appreciate any comments or feedback you can provide about Prospero. Do you enjoy the mix of Fund – application articles or are we missing something? Do you ever enter the competitions and if not, why not? Please send any comments, suggestions or feedback to us at: [email protected], before the next window now open issue’s mailing date of 5 August. Applications are invited for educational and hardship purposes from the Grace Wyndham Goldie (BBC) Trust Fund. The Trust Fund exists to help those engaged in broadcasting or an associated activity, now or in Crospero devised and compiled by Jim Palm the past, as well as their children and dependants. The Trustees of the Grace Wyndham Goldie 1. 2. Complete the square by using the clues; these apply only to words running across. (BBC) Trust Fund, in their discretion, will consider 3. 4. Then take these words in numerical; order giving assistance towards educational costs in and extract the letters indicated by a dot. small ways, such as travelling expenses, school 5. 6. If your answers are correct, these letters will outfits, books and additions to education awards. -

Final Impact Assessment

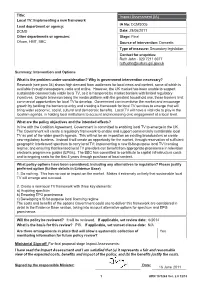

Title: Impact Assessment (IA) Local TV: Implementing a new framework IA No: DCMS005 Lead department or agency: DCMS Date: 28/06/2011 Other departments or agencies: Stage: Final Ofcom, HMT, BBC Source of intervention: Domestic Type of measure: Secondary legislation Contact for enquiries: Ruth John - 020 7211 6977 [email protected] Summary: Intervention and Options What is the problem under consideration? Why is government intervention necessary? Research (see para 34) shows high demand from audiences for local news and content, some of which is available through newspapers, radio and online. However, the UK market has been unable to support sustainable commercially viable local TV, as it is hampered by market barriers with limited regulatory incentives. Despite television being the media platform with the greatest household use, these barriers limit commercial opportunities for local TV to develop. Government can incentivise the market and encourage growth by tackling the barriers to entry and creating a framework for local TV services to emerge that will bring wider economic, social, cultural and democratic benefits. Local TV will have a vital role to play in the localism agenda, in holding local institutions to account and increasing civic engagement at a local level. What are the policy objectives and the intended effects? In line with the Coalition Agreement, Government is committed to enabling local TV to emerge in the UK. The Government will create a regulatory framework to enable and support commercially sustainable local TV as part of the wider growth agenda. This will not be an imposition on existing broadcasters or create new regulatory burdens. -

Market Impact Assessment of the BBC's Local Video Service

Market Impact Assessment of the BBC’s Local Video Service This is a non-confidential version of the statement. Redactions are indicated by “[ ]”. Statement Publication date: 21 November 2008 Market Impact Assessment of the BBC’s Local Video Service Contents Section Page 1 Executive Summary 1 2 Overview of analysis and conclusions 3 3 Introduction 34 4 Market research, modelling and take-up 39 5 Local and regional newspapers and associated web services 50 6 Local radio stations and associated web services 83 7 Regional TV and associated web services 106 8 Local TV and associated web services 120 9 Mobile TV services 126 10 Other relevant services 138 11 Possible modifications to the BBC proposed service 148 Annex Page 1 Joint BBC Trust / Ofcom description of service 159 2 Terms of Reference 175 3 Market research – regression analysis 178 4 Modelling approach and assumptions 184 5 Broader static impact on consumer and producer surplus 198 6 Framework for assessing dynamic impacts 208 7 Summary of stakeholder submissions 210 Market Impact Assessment of the BBC’s Local Video Service Section 1 1 Executive Summary 1.1 Ofcom (the Office of Communications) undertakes a market impact assessment (“MIA”) as part of the BBC Trust’s Public Value Test (“PVT”) regime to assess whether the BBC’s proposals to launch new services, or to amend existing services, would be in the wider public interest. The MIA, which is carried out independently by Ofcom, assesses the likely impact of proposed BBC services on commercial providers. The MIA does not consider whether the proposal meets the BBC’s public purposes in terms of likely value to licence fee payers. -

COMMERCIALLY VIABLE LOCAL TELEVISION in the UK a Review by Nicholas Shott for the Secretary of State for Culture, Olympics, Media and Sport

DECEMBER 2010 COMMERCIALLY VIABLE LOCAL TELEVISION IN THE UK A Review by Nicholas Shott for The Secretary of State for Culture, Olympics, Media and Sport LOCAL TV REVIEW IMPORTANT NOTICE This Final Report has been prepared by Nicholas Shott for The Secretary of State for Culture, Olympics, Media and Sport pursuant to the letter from the Secretary of State to Mr Shott dated 22nd June 2010. The Final Report is provided to the Secretary of State and no other recipient of the Final Report will be entitled to rely on it for any purpose whatsoever. Neither Mr Shott nor any member of the Steering Group who have assisted him (a) provides any representations or warranties (express or implied) in relation to the matters contained herein or as to the accuracy or completeness of the Final Report or (b) will owe any duty of care to, or have any responsibility, duty, obligation or liability to any third party in relation to the Final Report as a result of any disclosure of the Final Report to them and any reliance that they might seek to place on the Final Report. DECEMBER 2010 LOCAL TV REVIEW Contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 2 INTRODUCTION 7 2.1 Scope of this Study 7 2.2 Process and Structure 8 2.3 Market Context 9 3 KEY THEMES 15 3.1 Content and Programming 15 3.2 DTT Transmission 19 3.3 Delivery on Additional Platforms 22 3.4 Audience Promotion 23 3.5 Costs for Local TV 25 3.6 Revenue: Advertising and Sponsorship 27 3.7 Competition and Market Impact 32 3.8 Licensing and Development of Local Services and a National Backbone 33 3.9 Role of Public Service -

Local Video Public Value Test Final Conclusions

Local Video Public Value Test final conclusions 1 Contents 1. Introduction and Key Findings 5 2. The PVT Process to Date 7 3. Summary of the Provisional Conclusions 10 4. Consideration of Consultation Responses 12 5. The Trust’s Final Conclusions 25 Annex I Background to the Public Value Test 26 2 Glossary of Terms Charter The current Royal Charter governing the BBC DAB Digital Audio Broadcasting Dynamic impacts The effect of the BBC service on other services, once they have adjusted their behaviour in response to the BBC service Framework Agreement Framework Agreement dated July 2006 between the BBC and the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport MIA Market impact assessment, undertaken by Ofcom to assess the market impact of new BBC proposals. This forms part of the public value test, below On-demand Allows users to select, stream or download, store and view film and television programmes, usually within a certain timeframe, using a digital cable box or online service PVA Public value assessment, undertaken by the Trust to assess the value of BBC proposals, including value to licence fee payers, value for money and wider societal value. This forms part of the public value test, below PVT Public value test; significant changes to the BBC's UK Public Services must be subject to full and public scrutiny. The means by which this scrutiny takes place is the public value test. A PVT is a thorough evidence-based process which considers both the public value and market impact of proposals. During PVTs, the Trust will consult the public to ensure its decisions are properly informed by those who pay for the BBC Reach Measures reach of BBC’s service to its audience 3 Service licence The Trust aims to ensure that the BBC offers high quality and original services for all licence fee payers.