A Walk from Clerkenwell to Islington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autumn 2014 Incorporating Islington History Journal

Journal of the Islington Archaeology & History Society Journal of the Islington Archaeology & History Society Vol 4 No 3 Autumn 2014 incorporating Islington History Journal War, peace and the London bus The B-type London bus that went to war joins the Routemaster diamond jubilee event Significants finds at Caledonian Parkl Green plaque winners l World War 1 commemorations l Beastly Islington: animal history l The emigrants’ friend and the nursing pioneer l The London bus that went to war l Researching Islington l King’s Cross aerodrome l Shoreditch’s camera obscura l Books and events l Your local history questions answered About the society Our committee What we do: talks, walks and more Contribute to this and contacts heIslington journal: stories and President Archaeology&History pictures sought RtHonLordSmithofFinsbury TSocietyishereto Vice president: investigate,learnandcelebrate Wewelcomearticlesonlocal MaryCosh theheritagethatislefttous. history,aswellasyour Chairman Weorganiselectures,tours research,memoriesandold AndrewGardner,andy@ andvisits,andpublishthis photographs. islingtonhistory.org.uk quarterlyjournal.Wehold Aone-pagearticleneeds Membership, publications 10meetingsayear,usually about500words,andthe and events atIslingtontownhall. maximumarticlelengthis CatherineBrighty,8 Wynyatt Thesocietywassetupin 1,000words.Welikereceiving Street,EC1V7HU,0207833 1975andisrunentirelyby picturestogowitharticles, 1541,catherine.brighteyes@ volunteers.Ifyou’dliketo butpleasecheckthatwecan hotmail.co.uk getinvolved,pleasecontact reproducethemwithout -

A Beautifully Presented One Bedroom Garden Flat

A beautifully presented one bedroom garden flat City Road, Clerkenwell, London, EC1V £625,000 Leasehold (87 years remaining) 1 Bedroom • 1 Bathroom • 1 Reception Room Solid wood floors • Private courtyard garden • Own entrance • Spacious reception • Separate kitchen • Close to Angel tube • Moments from Regent's Canal About this property City Road connects Angel and A beautiful, well-proportioned, Old Street offering excellent bright, garden flat within a period transport links and plenty of terrace. Located just South of restaurants, nightlife and Angel Underground station, the shopping facilities. property is extremely well positioned for access to Angel, Angel tube station is the City, Hoxton, Shoreditch, Old approximately 380 yards and Old Street and King's Cross. Street Tube Station is approximately 0.7 Miles (Source: The flat, which benefits from its Streetcheck.co.uk). own private entrance, has been overhauled by the current owner and is finished to a high standard Tenure throughout with solid wood floors, Leasehold (87 years remaining) bespoke fitted wardrobes, high ceilings, shutters and column Local Authority radiators. The kitchen and Islington = Band C bathroom are both recently appointed and incredibly well Energy Performance presented. EPC Rating = C To the rear is a private, south Viewing facing courtyard garden complete All viewings will be accompanied with built-in masonry barbecue, and are strictly by prior which is perfect for entertaining. arrangement through Savills Clerkenwell Office. Telephone: +44 (0) 20 7253 2533. Local Information Michael Smit Clerkenwell City Road, Clerkenwell, London, EC1V +44 (0) 20 7253 2533 Gross Internal Area 495 sq ft, 46 m² savills savills.co.uk [email protected] Important notice Savills, its clients and any joint agents give notice that 1: They are not authorised to make or give any representations or warranties in relation to the property either here or elsewhere, either on their own behalf or on behalf of their client or otherwise. -

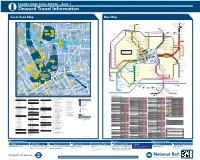

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 1 35 Wellington OUTRAM PLACE 259 T 2 HAVELOCK STREET Caledonian Road & Barnsbury CAMLEY STREET 25 Square Edmonton Green S Lewis D 16 L Bus Station Games 58 E 22 Cubitt I BEMERTON STREET Regent’ F Court S EDMONTON 103 Park N 214 B R Y D O N W O Upper Edmonton Canal C Highgate Village A s E Angel Corner Plimsoll Building B for Silver Street 102 8 1 A DELHI STREET HIGHGATE White Hart Lane - King’s Cross Academy & LK Northumberland OBLIQUE 11 Highgate West Hill 476 Frank Barnes School CLAY TON CRESCENT MATILDA STREET BRIDGE P R I C E S Park M E W S for Deaf Children 1 Lewis Carroll Crouch End 214 144 Children’s Library 91 Broadway Bruce Grove 30 Parliament Hill Fields LEWIS 170 16 130 HANDYSIDE 1 114 CUBITT 232 102 GRANARY STREET SQUARE STREET COPENHAGEN STREET Royal Free Hospital COPENHAGEN STREET BOADICEA STREE YOR West 181 212 for Hampstead Heath Tottenham Western YORK WAY 265 K W St. Pancras 142 191 Hornsey Rise Town Hall Transit Shed Handyside 1 Blessed Sacrament Kentish Town T Hospital Canopy AY RC Church C O U R T Kentish HOLLOWAY Seven Sisters Town West Kentish Town 390 17 Finsbury Park Manor House Blessed Sacrament16 St. Pancras T S Hampstead East I B E N Post Ofce Archway Hospital E R G A R D Catholic Primary Barnsbury Handyside TREATY STREET Upper Holloway School Kentish Town Road Western University of Canopy 126 Estate Holloway 1 St. -

No. 133 Upper Street . London . N1 1QP January 2013

28 Scrutton Street London EC2A 4RP UK www.kyson.co.uk No. 133 Upper Street . London . N1 1QP January 2013 . Design and Access Statement Contents 2 Introduction 03 Site Location 04 Map of London Location Map Site History and Context 06 Upper Street North Conservation Area - Historic Background Upper Street No. 133 Upper Street Access 09 Planning Context 10 Planning Appraisal 11 Sustainability 18 Sustainable Statement 20 Design 21 Existing Drawings 33 Overview Site Location Plan Floor Plans Elevations Site Sections Sections Proposed Drawings 47 Site Models Site Plan Demolition Proposal Floor Plans Elevations Site Sections Sections Contextual Drawings 68 Contextual Floor Plans Contextual Elevation No. 133 Upper Street . London . N1 1QP . January 2013 INTRODUCTION 3 Kyson, on behalf of our client, is seeking to gain Planning and Conservation Area consent for the demolition of 133B Upper Street, London, N1 1QP, and erection of a new 5 storeys building comprising the use of basement and ground floor as Restaurant (A3) and Residential (C3) uses at upper floors. The development proposals also incorporate alteration and a single storey extension at ground floor of the rear wing at 133 Upper Street. No. 133 Upper Street . London . N1 1QP . January 2013 Site Location 4 Location The application site is located on the western side of Upper Street within the London Borough of Islington. It is situated in the Upper Street North Conservation Area. Map of London Aerial View of London Aerial View of London Borough of Isllington No. 133 Upper Street . London . N1 1QP . January 2013 Site Location 5 Location Map View Southward Aerial View of No. -

Hoock Empires Bibliography

Holger Hoock, Empires of the Imagination: Politics, War, and the Arts in the British World, 1750-1850 (London: Profile Books, 2010). ISBN 978 1 86197. Bibliography For reasons of space, a bibliography could not be included in the book. This bibliography is divided into two main parts: I. Archives consulted (1) for a range of chapters, and (2) for particular chapters. [pp. 2-8] II. Printed primary and secondary materials cited in the endnotes. This section is structured according to the chapter plan of Empires of the Imagination, the better to provide guidance to further reading in specific areas. To minimise repetition, I have integrated the bibliographies of chapters within each sections (see the breakdown below, p. 9) [pp. 9-55]. Holger Hoock, Empires of the Imagination (London, 2010). Bibliography © Copyright Holger Hoock 2009. I. ARCHIVES 1. Archives Consulted for a Range of Chapters a. State Papers The National Archives, Kew [TNA]. Series that have been consulted extensively appear in ( ). ADM Admiralty (1; 7; 51; 53; 352) CO Colonial Office (5; 318-19) FO Foreign Office (24; 78; 91; 366; 371; 566/449) HO Home Office (5; 44) LC Lord Chamberlain (1; 2; 5) PC Privy Council T Treasury (1; 27; 29) WORK Office of Works (3; 4; 6; 19; 21; 24; 36; 38; 40-41; 51) PRO 30/8 Pitt Correspondence PRO 61/54, 62, 83, 110, 151, 155 Royal Proclamations b. Art Institutions Royal Academy of Arts, London Council Minutes, vols. I-VIII (1768-1838) General Assembly Minutes, vols. I – IV (1768-1841) Royal Institute of British Architects, London COC Charles Robert Cockerell, correspondence, diaries and papers, 1806-62 MyFam Robert Mylne, correspondence, diaries, and papers, 1762-1810 Victoria & Albert Museum, National Art Library, London R.C. -

Whose River? London and the Thames Estuary, 1960-2014* Vanessa Taylor Univ

This is a post-print version of an article which will appear The London Journal, 40(3) (2015), Special Issue: 'London's River? The Thames as a Contested Environmental Space'. Accepted 15 July 2015. Whose River? London and the Thames Estuary, 1960-2014* Vanessa Taylor Univ. of Greenwich, [email protected] I Introduction For the novelist A.P. Herbert in 1967 the problem with the Thames was simple. 'London River has so many mothers it doesn’t know what to do. ... What is needed is one wise, far- seeing grandmother.’1 Herbert had been campaigning for a barrage across the river to keep the tide out of the city, with little success. There were other, powerful claims on the river and numerous responsible agencies. And the Thames was not just ‘London River’: it runs for over 300 miles from Gloucestershire to the North Sea. The capital’s interdependent relationship with the Thames estuary highlights an important problem of governance. Rivers are complex, multi-functional entities that cut across land-based boundaries and create interdependencies between distant places. How do you govern a city that is connected by its river to other communities up and downstream? Who should decide what the river is for and how it should be managed? The River Thames provides a case study for exploring the challenges of governing a river in a context of changing political cultures. Many different stories could be told about the river, as a water source, drain, port, inland waterway, recreational amenity, riverside space, fishery, wildlife habitat or eco-system. -

EC1 Local History Trail EC1 Local Library & Cultural Services 15786 Cover/Pages 1-4 12/8/03 12:18 Pm Page 2

15786 cover/pages 1-4 12/8/03 12:18 pm Page 1 Local History Centre Finsbury Library 245 St. John Street London EC1V 4NB Appointments & enquiries (020) 7527 7988 [email protected] www.islington.gov.uk Closest Tube: Angel EC1 Local History Trail Library & Cultural Services 15786 cover/pages 1-4 12/8/03 12:18 pm Page 2 On leaving Finsbury Library, turn right down St. John Street. This is an ancient highway, originally Walk up Turnmill Street, noting the open railway line on the left: imagine what an enormous leading from Smithfield to Barnet and the North. It was used by drovers to send their animals to the excavation this must have been! (Our print will give you some idea) Cross over Clerkenwell Rd into market. Cross Skinner Street. (William Godwin, the early 18th century radical philosopher and partner Farringdon Lane. Ahead, you’ll see ‘Well Court’. Look through the windows and there is the Clerk’s of Mary Wollestonecraft, lived in the street) Well and some information boards. Double back and turn into Clerkenwell Green. On your r. is the Sessions House (1779). The front is decorated with friezes by Nollekens, showing Justice & Mercy. Bear right off St John Street into Sekforde Street. Suddenly you enter a quieter atmosphere...On the It’s now a Masonic Hall. In the 17th century, the Green was affluent, but by the 19th, as Clerkenwell was right hand side (rhs) is the Finsbury Savings Bank, established at another site in 1816. Walk on past heavily industrialised and very densely populated with poor workers, it became a centre of social & the Sekforde Arms (or go in if you fancy!) and turn left into Woodbridge Street. -

Clerkenwood’ the EC1 Area Has Long Been Attractive to Filmmakers Seeking a Historic Location

EC1 ECHO APR/MAY 2021 N 9 FREE NEWS FEATURES HISTORY EC1Echo.co.uk Migrateful’s new Lights, camera and A walk along EC1’s @EC1Echo cookery school action – Clerkenwell elusive aqueduct – opens shortly on film the New River EC1Echo@ /EC1Echo P 5 P 12–13 P 14–15 peelinstitute.org.uk Filming ‘The Last Letter’ in Wilmington Square © Filmfixer Welcome to ‘Clerkenwood’ The EC1 area has long been attractive to filmmakers seeking a historic location. Here, EC1 Echo finds out why the area is such a draw BY OLIVER BENNETT here thanks to company FilmFixer With its historic ambience, many How do they mask off modern life? which is, says senior film officer Tim films in Clerkenwell are period dra- “Obviously, visual effects take place With Georgian streets and squares, Reynard, “a third party contractor mas. “Obviously, the architecture and productions do use a ‘green normally busy cafes and streets, and that manages 14 London boroughs, lends itself very well to those kinds screen’,” says Tim. “But it’s abso- a number of period estates and tower including Islington.” of production,” says Tim. “Popular lutely remarkable what they can add blocks, Clerkenwell is one of those With staff that are all passionate locations include Exmouth Market, and remove, whether it’s a parking versatile areas that offer locations for about film, working for FilmFixer is Clerkenwell Green and Clerkenwell sign, yellow lines on a road – which many kinds of films. rewarding. “Everybody’s got a film Close, where the church and build- can be completely covered – or street Hence the high numbers of film and TV background,” says Tim. -

London National Park City Week 2018

London National Park City Week 2018 Saturday 21 July – Sunday 29 July www.london.gov.uk/national-park-city-week Share your experiences using #NationalParkCity SATURDAY JULY 21 All day events InspiralLondon DayNight Trail Relay, 12 am – 12am Theme: Arts in Parks Meet at Kings Cross Square - Spindle Sculpture by Henry Moore - Start of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail, N1C 4DE (at midnight or join us along the route) Come and experience London as a National Park City day and night at this relay walk of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail. Join a team of artists and inspirallers as they walk non-stop for 48 hours to cover the first six parts of this 36- section walk. There are designated points where you can pick up the trail, with walks from one mile to eight miles plus. Visit InspiralLondon to find out more. The Crofton Park Railway Garden Sensory-Learning Themed Garden, 10am- 5:30pm Theme: Look & learn Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, SE4 1AZ The railway garden opens its doors to showcase its plans for creating a 'sensory-learning' themed garden. Drop in at any time on the day to explore the garden, the landscaping plans, the various stalls or join one of the workshops. Free event, just turn up. Find out more on Crofton Park Railway Garden Brockley Tree Peaks Trail, 10am - 5:30pm Theme: Day walk & talk Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, London, SE4 1AZ Collect your map and discount voucher before heading off to explore the wider Brockley area along a five-mile circular walk. The route will take you through the valley of the River Ravensbourne at Ladywell Fields and to the peaks of Blythe Hill Fields, Hilly Fields, One Tree Hill for the best views across London! You’ll find loads of great places to enjoy food and drink along the way and independent shops to explore (with some offering ten per cent for visitors on the day with your voucher). -

—— 407 St John Street

ANGEL BUILDING —— 407 ST JOHN STREET, EC1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 6 THE LOCALITY 8 A SENSE OF ARRIVAL 16 THE ANGEL KITCHEN 18 ART AT ANGEL 20 OFFICE FLOORS 24 TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION 30 SUSTAINABILITY 32 LANDSCAPING 34 CANCER RESEARCH UK 36 AHMM COLLABORATION 40 SOURCES OF INSPIRATION 42 DERWENT LONDON 44 PROFESSIONAL TEAM 46 Angel Building 2 / 3 Angel Building 4 / 5 Located in EC1, the building commands the WELCOME TO heights midway between the financial hub of the City of London and the international rail THE ANGEL BUILDING interchange and development area of King’s Cross —— St. Pancras. With easy access to the West End, it’s at the heart of one of London’s liveliest historic The Angel Building is all about improving radically urban villages, with a complete range of shops, on the thinking of the past, to provide the best restaurants, markets and excellent transport possible office environment for today. A restrained links right outside. The Angel Building brings a piece of enlightened modern architecture by distinguished new dimension to the area. award-winning architects AHMM, it contains over 250,000 sq ft (NIA) of exceptional office space. With a remarkable atrium, fine café, and ‘IT’S A GOOD PLACE exclusively-commissioned works of contemporary TO BE’ art, it also enjoys exceptional views from its THE ANGEL enormous rooftop terraces. Above all, this is where This is a building carefully made to greatly reduce the City meets the West End. The Angel Building its carbon footprint – in construction and in is a new addition to this important intersection operation. -

Altea Gallery

Front cover: item 32 Back cover: item 16 Altea Gallery Limited Terms and Conditions: 35 Saint George Street London W1S 2FN Each item is in good condition unless otherwise noted in the description, allowing for the usual minor imperfections. Tel: + 44 (0)20 7491 0010 Measurements are expressed in millimeters and are taken to [email protected] the plate-mark unless stated, height by width. www.alteagallery.com (100 mm = approx. 4 inches) Company Registration No. 7952137 All items are offered subject to prior sale, orders are dealt Opening Times with in order of receipt. Monday - Friday: 10.00 - 18.00 All goods remain the property of Altea Gallery Limited Saturday: 10.00 - 16.00 until payment has been received in full. Catalogue Compiled by Massimo De Martini and Miles Baynton-Williams To read this catalogue we recommend setting Acrobat Reader to a Page Display of Two Page Scrolling Photography by Louie Fascioli Published by Altea Gallery Ltd Copyright © Altea Gallery Ltd We have compiled our e-catalogue for 2019's Antiquarian Booksellers' Association Fair in two sections to reflect this year's theme, which is Firsts The catalogue starts with some landmarks in printing history, followed by a selection of highlights of the maps and books we are bringing to the fair. This year the fair will be opened by Stephen Fry. Entry on that day is £20 but please let us know if you would like admission tickets More details https://www.firstslondon.com On the same weekend we are also exhibiting at the London Map Fair at The Royal Geographical Society Kensington Gore (opposite the Albert Memorial) Saturday 8th ‐ Sunday 9th June Free admission More details https://www.londonmapfairs.com/ If you are intending to visit us at either fair please let us know in advance so we can ensure we bring appropriate material. -

The New River Improvement Project 7Th September 2017 Claudia Innes

The New River Improvement Project 7th September 2017 Claudia Innes Community Projects Executive Corporate Responsibility Team ∗ Team of 18 - Education, community investment, volunteering and nature reserves ∗ Manage a £6.5 million community investment fund between 2014 and 2019 ∗ Aim to engage customers and communities through: ∗ environmental enhancement ∗ improving access and recreation ∗ educational outreach Governance • All funding applicants apply by form. • All spend is approved in advance by our Charities Committee • A Memorandum Of Understanding is generated to release the funds to the partner. 3 The New River – a brief history ∗ Aqueduct completed in 1613 by Goldsmith and Adventurer Hugh Myddelton and Mathematician Edward Wright. ∗ King James I agreed to provide half the costs on condition he received half of the profits ∗ Total cost of construction was £18,500. ∗ Essential part of London’s water supply. 48 million gallons a day are carried for treatment. The New River – a brief history ∗ Originally fed only by sources at Chadwell and Amwell Springs. ∗ The course of the New River now ends at Stoke Newington East Reservoir (Woodberry Wetlands). ∗ Water levels are regulated by sluices. Path development ∗ The New River Path was developed over 12 years at a cost of over £2 million ∗ 28 miles from Hertfordshire to North London. ∗ We have worked in partnership with, and with the support of, many organisations; including Groundwork, the New River Action Group, Friends of New River Walk, schools and communities, and all the local authorities