CARLI Digital Collections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt487035r5 No online items Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 Phone: (213) 741-0094 Fax: (213) 741-0220 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.onearchives.org © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Coll2007-020 1 Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Collection number: Coll2007-020 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives Los Angeles, California Processed by: Michael P. Palmer, Jim Deeton, and David Hensley Date Completed: September 30, 2009 Encoded by: Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ralph W. Judd collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Dates: 1848-circa 2000 Collection number: Coll2007-020 Creator: Judd, Ralph W., 1930-2007 Collection Size: 11 archive cartons + 2 archive half-cartons + 1 records box + 8 oversize boxes + 19 clamshell albums + 14 albums.(20 linear feet). Repository: ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. Los Angeles, California 90007 Abstract: Materials collected by Ralph Judd relating to the history of cross-dressing in the performing arts. The collection is focused on popular music and vaudeville from the 1890s through the 1930s, and on film and television: it contains few materials on musical theater, non-musical theater, ballet, opera, or contemporary popular music. -

Reginald De Koven Collection11.Mwalb02120

Reginald De Koven collection11.MWalB02120 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 30, 2021. eng Describing Archives: A Content Standard Brandeis University 415 South St. Waltham, MA URL: https://findingaids.brandeis.edu/ Reginald De Koven collection11.MWalB02120 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 4 Other Descriptive Information ....................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 5 - Page 2 - Reginald De Koven collection11.MWalB02120 Summary Information Repository: Brandeis University Creator: De Koven, Reginald, 1859-1920 Title: Reginald De Koven collection ID: 11.MWalB02120 Date [inclusive]: 1861-1920 Date [bulk]: 1861-1920 Physical Description: 18.00 Linear Feet Physical Description: 35 manuscript boxes -

Ceriani the Reception of Alberto Franchetti’S Works in the United States 271 Marialuisa Pepi Franchetti Attraverso I Documenti Del Gabinetto G.P

Alberto Franchetti. l’uomo, il compositore, l’artista Atti del convegno internazionale Reggio Emilia, 18-19 settembre 2010 a cura di Paolo Giorgi e Richard Erkens Alberto Franchetti. L’uomo, il compositore, l’artista il compositore, L’uomo, Franchetti. Alberto associazione per il musicista ALBERTO FRANCHETTI Alberto Franchetti l’uomo, il compositore, l’artista associazione per il musicista FRANCHETTI ALBERTO a cura di Paolo Giorgi e Richard Erkens € 30,00 LIM Libreria Musicale Italiana Questa pubblicazione è stata realizzata dall’Associazione per il musicista Alberto Franchetti, in collaborazione con il Comune di Regio Emilia / Biblioteca Panizzi, e con il sostegno di Stefano e Ileana Franchetti. Soci benemeriti dell’Associazione per il musicista Alberto Franchetti Famiglia Ponsi Stefano e Ileana Franchetti Fondazione I Teatri – Reggio Emilia Fondazione Pietro Manodori – Reggio Emilia Hotel Posta – Reggio Emilia Redazione, grafica e layout: Ugo Giani © 2015 Libreria Musicale Italiana srl, via di Arsina 296/f, 55100 Lucca [email protected] www.lim.it Tutti i diritti sono riservati. Nessuna parte di questa pubblicazione potrà essere riprodot- ta, archiviata in sistemi di ricerca e trasmessa in qualunque forma elettronica, meccani- ca, fotocopiata, registrata o altro senza il permesso dell’editore, dell’autore e del curatore. ISBN 978-88-7096-817-0 associazione per il musicista ALBERTO FRANCHETTI Alberto Franchetti l’uomo, il compositore, l’artista Atti del convegno internazionale Reggio Emilia, 18-19 settembre 2010 a cura di Paolo Giorgi e Richard Erkens Libreria Musicale Italiana Alla memoria di Elena Franchetti (1922-2009) Sommario Presentazione, Luca Vecchi xi Premessa, Stefano Maccarini Foscolo xiii Paolo Giorgi – Richard Erkens Introduzione xv Alberto Franchetti (1860-1942) l’uomo, il compositore, l’artista Parte I Dal sinfonista all’operista internazionale Antonio Rostagno Alberto Franchetti nel contesto del sinfonismo italiano di fine Ottocento 5 Emanuele d’Angelo Alla scuola di Boito. -

Untitled, It Is Impossible to Know

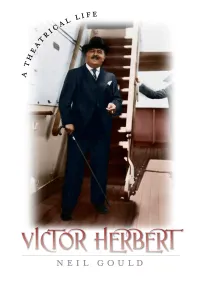

VICTOR HERBERT ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:09 PS PAGE i ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:09 PS PAGE ii VICTOR HERBERT A Theatrical Life C:>A<DJA9 C:>A<DJA9 ;DG9=6BJC>K:GH>INEG:HH New York ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE iii Copyright ᭧ 2008 Neil Gould All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gould, Neil, 1943– Victor Herbert : a theatrical life / Neil Gould.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8232-2871-3 (cloth) 1. Herbert, Victor, 1859–1924. 2. Composers—United States—Biography. I. Title. ML410.H52G68 2008 780.92—dc22 [B] 2008003059 Printed in the United States of America First edition Quotation from H. L. Mencken reprinted by permission of the Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore, Maryland, in accordance with the terms of Mr. Mencken’s bequest. Quotations from ‘‘Yesterthoughts,’’ the reminiscences of Frederick Stahlberg, by kind permission of the Trustees of Yale University. Quotations from Victor Herbert—Lee and J.J. Shubert correspondence, courtesy of Shubert Archive, N.Y. ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE iv ‘‘Crazy’’ John Baldwin, Teacher, Mentor, Friend Herbert P. Jacoby, Esq., Almus pater ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE v ................ -

China and the West: Music, Representation, and Reception

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Revised Pages China and the West Revised Pages Wanguo Quantu [A Map of the Myriad Countries of the World] was made in the 1620s by Guilio Aleni, whose Chinese name 艾儒略 appears in the last column of the text (first on the left) above the Jesuit symbol IHS. Aleni’s map was based on Matteo Ricci’s earlier map of 1602. Revised Pages China and the West Music, Representation, and Reception Edited by Hon- Lun Yang and Michael Saffle University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © 2017 by Hon- Lun Yang and Michael Saffle All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2020 2019 2018 2017 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Yang, Hon- Lun, editor. | Saffle, Michael, 1946– editor. Title: China and the West : music, representation, and reception / edited by Hon- Lun Yang and Michael Saffle. Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016045491| ISBN 9780472130313 (hardcover : alk. -

July 1910) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 7-1-1910 Volume 28, Number 07 (July 1910) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 28, Number 07 (July 1910)." , (1910). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/560 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VASSA* COLLEGE LIBRARY JULY 1910 SEETH0V1 AbbeGELlNEK MoIaHT BEETHOVEN AND MOZART Baroness DOROTHEA MOZART'S WIFE Princess ERDODY S'Year THEO. PRESSER CO THE ETUDE Intermediate Studies LEADING TO VELOCITY PLAY¬ ING AND MUSICIANSHIP New Publications MELODIC STUDIES -— FOR EQUALIZATION OF THE HANDS Premiums and Special Offers By ARNOLDO SARTORIO Easy Engelmann Album Op. 853 Price, SI.00 Nature Studies Musical Thoughts lor Third grade studies of unusual excel¬ of Interest to Our Readers A Song Cycle for the Ten lence, suitable for a variety of pur¬ A MONTHLY JOURNAL FOR THE MUSICIAN, THE little Tots FOR THE PIANO poses ; independence of hands, equal¬ MUSIC STUDENT, AND ALL MUSIC LOVERS. -

Marshall* Penitentiary Reformatory J All Jf/SHEST Type Ready-To We a Pl, Were Other and at One Time a Davis I This Vote for Champion

Many State's Prison and Penitentiary Sentences Given by Judge Osborne State's prison terms were meted out to half a dozen offenders by Judge Harry V. Osborne in the Court of Quarter Sessions and Special Ses- sions yesterday afternoon. Many (Continued from First Fane.) and sen- HoJfcombe Ward, former national Marshall* penitentiary reformatory j all Jf/SHEST Type Ready-To We a pl, were other and at one time a Davis i this vote for Champion. Frank Kra- tences also hande dout to champion 1912 mer, as I am a great cyclist fan and lawbreakers. cup player: Walter Merrill Hall, of love well illustrated eUS Has eapriclousness is In Reginald De Koven's a great reader of the Morning and Charles Gaines, a negro with a long middle States champion; Charles M. 807’813 Broad Street. beautiful musical comedy, "The Fancing Master," given by the Olympic Evening Star. I was raised in Har- record, was given a term of not less Bull, jr.. the Crescent A. C. star; N. and F soccer foot- than two nor more than three — rison, years THEPark J., played Harold Throckmorton. Princeton In- Opera Company at the Newark Theatre. Francesca, Hudson was masquerading ball for the West football m the Trenton prison. Gaines terscholastic titleholder: William H. as Francesco, a master, falls in love with teams. This last winter I came to tound of Emmett fencing Fortunio, an impoverished guilty assaulting and a McKim, of Yale University, Continuation nobleman who Is the duke of St. Louis to play for the Ben Miller's Daniels, of 14 Vesey street, with Sade rightful Milan. -

November 1946) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 11-1-1946 Volume 64, Number 11 (November 1946) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 64, Number 11 (November 1946)." , (1946). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/189 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - {TIM, ELIZABETH Al Her Royal Hi$\mess/ rrincesjr«tif to flic lln one of Grea Britain, after receiving fh« De^PI ni versify of London \&4 summer. The Degree was preSM C han cellor ol the University. P it childhood. S i n ce her •JfRVICH DR. HENRY S. FRY, dis- the THE OPENING PERFORMANCE of tinguished organist and fall season at the City Center Theatre, choral conductor, for the New York, in September, saw New thirty-four years organ- York City Opera Company give a truly Numbers ist and choirmaster at outstanding performance of “Madama Piano St. Clements' Church, Butterfly.” Camilla Williams, sensational Philadelphia, died in young Negro soprano, headed a cast of Priority-Deserving that city on September inspired singers, and with Laszlo Halasz 6, at the age of seventy- Prelude conducting, the presentation, according Dr. -

September 1929) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 9-1-1929 Volume 47, Number 09 (September 1929) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 47, Number 09 (September 1929)." , (1929). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/771 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 7he Journal of the cMusical Home Everywhere CESAR FRANCK, THE GREAT BELGIAN MASTER PRICE 25 CENTS September 1929 S2.00 A YEAR SEPT EM BEE 1929 Patje 629 “A HANDICAP TO THE PUPIL IS A HANDICAP TO THE TEACHER Folksongs and STUDY THESE PICTURES! Folk Songs cnc Famous Picture- Famous Pictures HS1C itidy Now is Obe ® '-Jvr Picnc Beginners I^qpT For Piano Beginners with Words, Color Charts, 1 "" and Cut-out Cards By When Teachers Use Books Like These With Young Beginners Mary Bacon Mason A Little Supplemen¬ Price, $1.00 This Very First Piano tary Book for Child Book Irresistibly Appeals Pianists of Which IT IS nothing unusual these days to hear MUSIC AT EYE LEVEL! Comfort¬ to the Child Thousands are Used MUSIC TOO FAR AWAY! Muscles able, relaxed, eyes used normally. -

American Opera, Operetta & Musical

J & J LUBRANO MUSIC ANTIQUARIANS AMERICAN OPERA, OPERETTA & MUSICAL THEATRE 6 Waterford Way, Syosset, NY 11791 USA Telephone 516-922-2192 E-mail [email protected] www.lubranomusic.com ORDERING INFORMATION You may place orders from this list: - By e-mail to [email protected] - By telephone to 516-922-2192 - Through our secure website at www.lubranomusic.com v ILLUSTRATIONS of all items are available on our website at www.lubranomusic.com v 1. ARGENTO, Dominick 1927- The Aspern Papers Opera in two acts Libretto by the composer based on the Henry James novella. n.p.: Boosey & Hawkes [PN VSB-157], [1991]. Folio. Original publisher's wrappers illustrated with a photograph by Phil Schexnyder. [i] (title), [i] (copyright), [i] (commission, notes on first performance, named cast list), [i] (synopsis of scenes), [i] (characters and setting), [i] (synopsis), [i] (instrumentation), [i] (blank), 236 pp. First Edition. "In writing the libretto for his opera The Aspern Papers (1988), Argento moved Henry James’s setting from Venice to the shores of Lake Como in order to recreate the ambience of 19th-century operatic life as experienced by the artists who resided there… [Argento's] harmony teacher, Nicolas Nabokov, urged him to focus on composition, and through this influence as well as contact with the Baltimore composer Hugo Weisgall, Argento’s pronounced gift for vocal writing was furthered... While [his] vocal music is often described as eclectic, several characteristics recur as unifying hallmarks. The theme of self-discovery permeates his entire output. Further, Argento claims his compositional technique exists only in so far as it allows him to effectively communicate text and subtext, resulting in a uniquely intimate relationship between the text and his music." Virginia Saya and R. -

VICTRC Dancing and Music EE Publications

THE MORNING OREGONIAN, SATURDAY, JANUARY IT, 1920 son will be postmaster of Bend, after in-la- w, a fine young officer, very a long, bitter contest In which It was worthy, but one who lost his ship DESPERADO CAUGH T necessary' to invoke a curious ruling SIMS-I- HEATED IN without injuring the enemy, was rec- MX CTIS of the department to prevent another ommended for the navy cross and re- man from getting the job. The other ceived the D. S. M.," Admiral Sims . I candidate was J. W. Moore, of Bend, said. "That is what all naval officers BY PRESlDErJ T at Redmond, who would TILT OVER MEDALS complain of, what has reduced naval RELATE BRUTALITIES have made away with the job easily morale to zero." in the civil service examinations had The admiral said he had recom not the department ruled that he was mended Lieutenant A. L. Gates and ineligible because he was not a resi- Ensign H. G. Hammann for medals ol dent of Bend at the time that the va- honor because of exceptional heroism En- cancy occurred in the Bend office. and Gates had finally received a D. Price the Fusillade on Broadway "Service Morale Knocked to S. M. got a navy Senate Committee Hears of Hudson's appointment was demand- while Hammann ed by the organization democrats ot cross. Lieutenant Frank Bruce, de- Good Villa. dangers New Yorkers. Oregon. His nomination was sent Pieces," Admiral Says. ceased, also recommended for the First Word for to the senate today. medal of honor, was reduced to a navy William I. -

A Survey of Professional Operatic Entertainment in Little Rock, Arkansas: 1870-1900 Jenna M

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 A survey of professional operatic entertainment in Little Rock, Arkansas: 1870-1900 Jenna M. Tucker Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Tucker, Jenna M., "A survey of professional operatic entertainment in Little Rock, Arkansas: 1870-1900" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3766. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3766 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A SURVEY OF PROFESSIONAL OPERATIC ENTERTAINMENT IN LITTLE ROCK, ARKANSAS: 1870-1900 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts In The School of Music by Jenna Tucker B.M., Ouachita Baptist University, 2002 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2004 May 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I praise God for the grace and mercy that He has shown me throughout this project. Also, I am forever grateful to my major professor, Patricia O‟Neill, for her wisdom and encouragement. I am thankful to the other members of my committee: Dr. Loraine Sims, Dr. Lori Bade, Professor Robert Grayson, and Dr. Edward Song, for their willingness to serve on my committee as well as for their support.