Assessing Western Australian Year 11 Students' Engagement with Theory in Visual Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Article} {Profile}

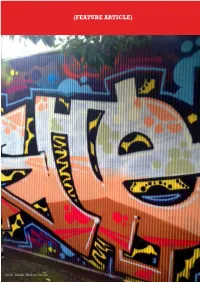

{PROFILE} {PROFILE} {FEATURE ARTICLE} {PROFILE} 28 {OUTLINE} ISSUE 4, 2013 Photo Credit: Sharon Givoni {FEATURE ARTICLE} Street Art: Another Brick in the Copyright Wall “A visual conversation between many voices”, street art is “colourful, raw, witty” 1 and thought-provoking... however perhaps most importantly, a potential new source of income for illustrators. Here, Melbourne-based copyright lawyer, Sharon Givoni, considers how the laws relating to street art may be relevant to illustrators. She tries to make you “street smart” in an environment where increasingly such creations are not only tolerated, but even celebrated. 1 Street Art Melbourne, Lou Chamberlin, Explore Australia Publishing Pty Ltd, 2013, Comments made on the back cover. It canvasses: 1. copyright issues; 2. moral rights laws; and 3. the conflict between intellectual property and real property. Why this topic? One only needs to drive down the streets of Melbourne to realise that urban art is so ubiquitous that the city has been unofficially dubbed the stencil graffiti capital. Street art has rapidly gained momentum as an art form in its own right. So much so that Melbourne-based street artist Luke Cornish (aka E.L.K.) was an Archibald finalist in 2012 with his street art inspired stencilled portrait.1 The work, according to Bonham’s Auction House, was recently sold at auction for AUD $34,160.00.2 Stencil seen in the London suburb of Shoreditch. Photo Credit: Chris Scott Artist: Unknown It is therefore becoming increasingly important that illustra- tors working within the street art scene understand how the law (particularly copyright law) may apply. -

Theoretical Issues and Conceptual Framework for Physical Facilities Design in Hospital Buildings

Journal of Architectural Environment & Structural Engineering Research | Volume 04 | Issue 01 | January 2021 Journal of Architectural Environment & Structural Engineering Research https://ojs.bilpublishing.com/index.php/jaeser ARTICLE Theoretical Issues and Conceptual Framework for Physical Facilities Design in Hospital Buildings Akinluyi Muyiwa L.1* Fadamiro Joseph A.2 Ayoola Hezekiah A.2 ALADE Morakinyo J.3 1. Department of Architecture, Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti (ABUAD), Nigeria 2. Department of Architecture, Federal University of Technology (FUTA) , Akure, Ondo- State, Nigeria 3. Directorate of Physical Planning and Development (DPPD) Living Faith Church Canaan land ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history This study reviewed the theoretical issues relating to morphological and Received: 29 July 2020 psychological design issues in hospital building design evaluation. The study of morphological configurations design issues, concentrates on the el- Accepted: 30 October 2020 ements of building, shape/form, the structure of the environment, the struc- Published Online: 31 January 2021 tural efficiency and the architectural appearance of the hospital building forms. The psychological design issues focused on the essential issues re- Keywords: lating to Proximity, Privacy and Wayfindings. Through the literature review Theories of previous models such as, Khan (2012) Operational Efficiency Model, Haron, Hamid and Talib Usability Framework, (2012), Zhao, Mourshed & Framework Wright (2009) Model, Alalouch, Aspinall & Smith Model (2016) and Hill Physical facilities & Kitchen (2009). A conceptual framework for physical facilities design Hospital building evaluation and satisfaction in hospital buildings was developed. The study, however, provides useful information for the development of a design framework that can inform policy on hospital buildings. 1. Introduction policy strategies for renovation and construction of new hospital buildings and environmental facilities to im- 1.1 Background to the Study prove the current healthcare situation. -

Conceptual Framework

Conceptual Framework for the Purpose of Measurement of Cooperatives and its Operationalization Conceptual Framework on Measurement of Cooperatives and its Operationalization Report discussed at the COPAC Technical Working Group on Cooperative Statistics Meeting Geneva, May 2017 International Labour Office • Geneva Copyright © International Labour Organization 2017 First published 2017 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Conceptual Framework for the Purpose of Measurement of Cooperatives and its Operationalization / International Labour Office – Geneva: ILO, 2017. ISBN: 978-92-2-129954-7 (web pdf) The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office. -

A Critical Theory and Postmodernist Approach to the Teaching of Accounting Theory

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Southern Queensland ePrints A Critical Theory and Postmodernist Approach to the teaching of Accounting Theory by Kieran James* Charles Sturt University Acknowledgements The author gratefully acknowledges the helpful comments of David Ardagh, Jenny Kent, Graeme Rose, seminar participants at Charles Sturt University, two anonymous reviewers, the editor (Tony Tinker), and especially the encouraging words of Mary Kaidonis, on earlier versions of this manuscript. Grateful thanks are also extended to Jenny Leung for typing up the interview transcripts, to Jenny Leung and Simon Yong for interpreting one of the interviews where the interviewee chose to receive and answer questions in Chinese Mandarin, and to Setsuo Otsuka for introducing me to the fascinating sociology of education literature. * Lecturer in Commerce, School of Commerce, Charles Sturt University, Locked Bag 588, Wagga Wagga NSW 2678, Australia. Tel: +61 2 69332518. E-mail address: [email protected] (K. James). 1 A Critical Theory and Postmodernist Approach to the teaching of Accounting Theory Abstract This paper outlines my teaching philosophy for the Accounting Theory subject. A Critical Theory and Postmodernist approach is recommended, which makes full use of non-accounting “tangential” material (Boyce, 2004) and material from popular culture (Kell, 2004; Nilan, 2004). The paper discusses some classroom interactive activities, as well as interview results from interviews conducted with eleven international students and one Australian student at Charles Sturt University. The teaching approach proposed in this paper is to conduct classroom interactive activities which study theories and research results from a range of disciplines in order to illustrate key points that apply equally as much to accounting theories and the accounting research process, e.g. -

Figure 1. Jianguo Village

Art Practice as Research: A Global Perspective Judith A. Briggs Illinois State University Nicole DeLosa Hornsby Girls’ High School ABSTRACT This case study explored how seven New South Wales (NSW) tenth grade students, following their art teacher’s prompts, engaged in art practice as research. They analyzed their creative process, researched artists’ forms and concepts, and conceptualized ideas to make critical interdisciplinary connections. They linked this research to their own knowledge and experiences to create and reflect upon artworks that had personal meaning and led to personal discoveries. Students used visual arts process diaries as research texts to record and communicate in both written and visual forms, revisit and plan ideas, reflect, and come to new conclusions. Students employed NSW Syllabi language as a metacognitive tool to recognize their approaches to research and art making. Students made metaphorical and symbolic connections, engaged in social critique, asked questions, and told their stories in this learning process. KEYWORDS: art practice as research; visual arts process diaries; metacognition AUTHOR NOTE: Nicole DeLosa is now in the Art Department of Pymble Ladies’ College. This research was supported in part by an Illinois State University Mills Grant. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Judith Briggs, School of Art, Illinois State University, Normal, IL 61790-5620 E-mail: [email protected] While there is no consensus theorizing art practice, art practice as research (APR) can be a site for knowledge construction and meaning making, situated in global systems, communities, and cultures. These global systems are not homogenous but represent diverse and sometimes conflicting viewpoints that reflect the experiences of people from various regions and backgrounds who have different degrees of access to opportunities and privileges (Manifold, Willis, & Zimmerman, 2016). -

Artworks from the Coventry Exhibition

Artworks from the Coventry Exhibition Primary + Secondary Education Resource Contents • Teacher Notes, page 3 + 4 • Introduction, page 5 • Resources, page 6 • Abstract Expressionism, page 7 + 8 • Hard Edge Abstraction, page 9 + 10 • Colour Field Painting, page 11 + 12 • Public Art + Kaldor Public Projects #1, page 13 + 14 • Performance Art + Kaldor Public Projects #5, page 15 + 16 • Figuration and Portraiture, page 17, 18 + 19 • Sculpture, page 20 • Collage, page 21 Front Page Features: Tim Lewis Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, 1974 Oil on Canvas 92 x 92.5cm Gift of Chandler Coventry 1979 2 Teachers Notes • The Coventry education resource invites students to This resource is designed for: This resource includes the following learning activities: engage with influential modern and contemporary art • Primary and Secondary students and can be movements through responding and making. adapted for Early Learning or Tertiary students. Discuss: Talking points and research questions are • By participating in artmaking and art theory students • It is aimed at Visual Arts students provided to stimulate contemplation, investigation and will learn how different visual representations of art with relevance to English, Philosophy, understanding. Offering opportunities for students to can communicate meaning. Science and Humanities, engage with art theory, such as the critical and and Social Sciences students. historical aspects in art through collaborative and • Both Primary and Secondary aged students are This resource may be used: independent inquiry. catered for in a range of sequenced activities: Teachers • To complement an experience of the Coventry Observe: Analysis of different aspects in creative Discussion, Observation and Make. exhibition through activities and ideas to assist artmaking, such as techniques, processes and visuals • This resource is directly linked to the NSW curriculum with preparation for the gallery visit. -

THE ROLE of ARTS and CULTURE in MODERN CITIES: Making Art Work in Toronto and New York by Shoshanah Barbara Diane Goldberg Abstr

THE ROLE OF ARTS AND CULTURE IN MODERN CITIES: Making Art Work in Toronto and New York by Shoshanah Barbara Diane Goldberg Abstract Cities throughout the world currently are exploring ways that arts and culture can serve as an economic engine, build name recognition and become a source of civic pride through a mix of policy, branding, and economic development. I examine the relationship between cultural policy and the increased presence of arts and culture on the economic development agenda in Toronto and New York during the decade of the 2000s. I hypothesize that New York is more driven by economic motivations, and that Toronto’s interest lies in the brand building aspect of arts and culture in city building. This dissertation is a comparative case study that investigates the increased presence of arts and culture in the economic development toolkits of Toronto and New York over the decade. Archival and historical data, in addition to interviews with elite actors provide a rich cache with which to answer the thesis question. Through the use of agenda setting theory, I find ways that arts and culture have been integrated into policy- making and urban planning for economic development in each city. I observe that Toronto and New York are building and facilitating cultural districts, attracting and retaining creative workers, and articulating economic arguments for arts and culture in order to generate revenues and secure government and private support. Each city underwent a shock during the early part of the decade. For Toronto, it was the endogenous shock of amalgamation, and for New York the exogenous shock of 9/11. -

Street Art – Legally Speaking

Legally Speaking: Street Art Intellectual property lawyer, Sharon Givoni, spends a vast amount of time working with professional photographers. While most cases involve the photographer taking legal action, they can also easily find themselves as the defendant. One example is when photographing street art, and Sharon has kindly taken the time to discuss this area of law. Street art has gained credibility as a legitimate way for artists to communicate their works to the public outside of the confines of the mainstream art world. The art takes various forms, ranging from bright alleyways to large-scale murals, sanctioned and unsanctioned alike. ‘More than ever before, photographers are an essential part of this scene,’ Lou Chamberlin wrote in her book, Street Art This photograph taken by Melbourne. ‘Known as paint spotters, they spend their spare Chris Scott shows graffiti in time chasing and documenting new pieces as soon as they an incidental fashion go up.’ A consequence of this, however, is the raft of legal issues that could potentially arise for photographers of street art. Imagine the following scenarios: – You photograph street art and reproduce it on a canvas with other images that you superimposed to create ‘art’ which you sell at a gallery. You are then surprised to receive a letter of demand from the street artist’s lawyer claiming a share of the sale. – You conduct a shoot for a magazine in an alleyway in Melbourne. In the background of the shot is some street art. Will publishing the photographs be an infringement of copyright? What if it is impossible to determine who created the art? – You take photographs of street art, frame and sell them. -

Making Sense of the World Through Art Symposium

Making Sense of ArtMaking Through the World Image: Tyrown Waigana, 2021, A Nice Place to Hate Yourself, 61 x 51 x 4 cm This symposium runs alongside the Gallery25 & THERE IS exhibition, Dark Side curated by Ted SNELL and featuring artists: Tarryn GILL | Carla ADAMS | Nicola KAYE & Stephen TERRY + Lyndall ADAMS + Marcella POLAIN | Paul UHLMANN | Roderick SPRIGG | Mary MOORE | Sharyn EGAN | Anna NAZZARI | Stormie MILLS | D’Arcy COAD | Tyrown WAIGANA symposium When: 10.15am–5pm, Friday, 11 June, 2021 Location: Building 10.131 Lecture Theatre and Building 10 Foyer, ECU, Mt Lawley Campus— link to campus maps Key contact: ECU Galleries, [email protected] Tickets: this event is free—bookings essential via TryBooking TryBooking link (attend in person) TryBooking link (webinar) Additional links: ECU Galleries National Art School (NAS) microsite Making Sense of the World Through Art symposium The Making Sense of the World Through Art symposium is part of a national exploration of mental health and wellbeing. ECU Galleries have partnered with the National Art School in Sydney to present Frame of mind: Mental health and the Arts. Artists and experts from WA and NSW will participate in this innovative public program to explore the mental health challenges faced by artists, and how artists engage with mental health themes within their work. themes of the symposium include: Making Sense, Finding Solace, Taking Control and Confronting Fear. Program Overview: Time Place Activity Presenter 10:15am Building 10 Foyer registration and coffee Welcome -

REMI ROUGH Remi Rough (B

REMI ROUGH Remi Rough (b. London, 1971) SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Volume, MOCA London. London, UK Interlude (With Peter Lamb & Charley Peters, House of St Barnabas. London UK Morning Dynamics, External mural project with MTRHK and Swir Properties Arts. Hong Kong Syncopation (With LX One), Zimmerling & Jungfleisch. Saarbrucken, DE 2017 Sound pigments, Magda Danysz Gallery, Paris FR Symphony of systematic minimalism, Wunderkammen Gallery, Rome IT 2016 Post, Speertstra. Bursins CH 2015 Home, Scream Gallery. London UK 2014 Motivational Therapy, Whitewalls Gallery. San Francisco US Further Adventures In Abstraction, Soze Gallery. Los Angeles US Flow with John ‘Crash’ Matos, Dorian Grey Gallery. New York US 2013 Excuse my French with RCF1, Galerie Celal. Paris FR 2012 In the presence of Angels, Soze Gallery. Los Angeles US How to use colour & manipulate people, Unit 44 Gallery. Newcastle UK 2011 Selected Moments with Stormie Mills, Unit 44 Gallery. Newcastle UK A (with Steve More), Blackall Studios. London UK 2009 ProjectRoom (with Jaybo), ProjectRoom. Berlin DE Lost colours and alibis, Urban Angel Gallery. London UK 2008 Coded Language, Peacock Visual Arts. Aberdeen UK 2007 Repetition, Rhythm & Rough, Nancy Victor Gallery. London UK SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2019 Graffuturism Paris, L’Alternatif. Paris FR 2018 Art from the streets, Art Science Museum, Singapore. 2017 Compendium, Treason Gallery, Seattle US Re-Define, Dallas Contemporary, Dallas US 2016 Jidar, Museé Mohammed VI. Rabat, MA MB6 Marrakech Biennale, Marrakech, MA 2015 15 Classes, St Jean De Luz FR Street Art, Fine Art, Pace Gallery London UK Public Provocations, Colab Gallery. Weil am Rhein DE Masters of Street Art, Magda Danysz Gallery. -

Teresa Burga, Trailblazing Peruvian Conceptualist Artist, Has Died, Aged 86

Teresa Burga, trailblazing Peruvian conceptualist artist, has died, aged 86 Although overlooked by art institutions until only recently, she continued to create work about artificial systems and bureaucracies during a 30-year career in Lima's customs office WALLACE LUDEL 12th February 2021 22:32 GMT Teresa Burga in 2019 Photo: Ross Collab Teresa Burga, a trailblazer in Latin American Conceptualism, has died, aged 86. The Ministry of Culture of Peru, where she lived and worked for most of her life, announced her death on Twitter on Thursday, and it has been confirmed by her New York gallery Alexander Gray Associates as well as her Berlin gallery, Galerie Barbara Thumm. Burga was born in 1935 in the port city of Iquitos, but moved as a child to Lima with her parents. After initially training as an architect, in 1966 she became one of six Lima-based artists who formed Grupo Arte Nuevo, a collective that wanted to propel the contemporary movements of Pop, Minimalism, Op Art, and happenings in Peru. In 1968, she travelled to the US on a Fulbright scholarship where she studied at the Art Institute of Chicago for two years, receiving her MFA in 1970. Throughout this time, Burga further pushed the conceptual elements of her work and questioned conventional notions of artistic authorship by creating objects that could be replicated by anyone through detailed schematics that she made. In 1971, she returned to Peru, which was then under the authoritarian rule of Juan Velasco Alvarado. Living under a regime unfavorable to conceptual art, Burga procured a job designing solutions to enhance administrative efficiency in digital information systems for Peru’s General Customs Office, a position she held for 30 years, and during which her artistic career drifted into obscurity. -

Assessing Western Australian Year 11 Students' Engagement with Theory in Visual Arts

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2015 Assessing Western Australian Year 11 students’ engagement with responding in Visual Arts Julia Elizabeth Morris Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Art Education Commons Recommended Citation Morris, J. E. (2015). Assessing Western Australian Year 11 students’ engagement with responding in Visual Arts. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1627 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1627 Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2015 Assessing Western Australian Year 11 students’ engagement with responding in Visual Arts Julia Elizabeth Morris Edith Cowan University Recommended Citation Morris, J. E. (2015). Assessing Western Australian Year 11 students’ engagement with responding in Visual Arts. Retrieved from http://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1627 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. http://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1627 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth).