Nab Final Volume 2 P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EEO Public File Report for April 1, 2018-March 31, 2019

EEO Public File Report for April 1, 2018-March 31, 2019 The purpose of this EEO Public File Report (“Report”) is to comply with Section 73.2080(c)(6) of the FCC’s 2002 EEO Rule. This Report has been prepared on behalf of the Station Employment Unit that is comprised of the following stations: Call Sign Community FIN WTAW College Station, TX 87145 KZNE College Station, TX 07632 KNDE College Station, TX 07631 KWBC College Station, TX 40912 KAGC Bryan, TX 16983 KPWJ Kurten, TX 166036 KVMK Wheelock, TX 189519 WTAW-FM Buffalo, TX 190405 KKEE -FM Centerville, TX 191507 A: Full Time Vacancies filled during the past year Job Title Date filled Source of hire Persons interviewed Navasota TX 3/2018 Promotion 3 Announcer Navasota TX 6/2018 Promotion 3 Announcer Morning Host 9/2018 All Access 4 Afternoon Host 10/2018 All Access 8 B: Recruitment Referral Sources Used to Seek Candidates for Each Position Recruitment Source for Afternoon Host Position Interviewees Positions hired from this from this source source All Access 8 Afternoon Host All Access Music Group 28955 Pacific Coast Highway Malibu, CA 90265 The Eagle (newspaper) 0 Classified Advertising Department 1729 Briarcrest Drive P.O. Box 3000 Bryan, TX 77802 Total 8 Recruitment Source for Morning Host Position Interviewees Positions hired from this from this source source All Access 4 Morning Host All Access Music Group 28955 Pacific Coast Highway Malibu, CA 90265 The Eagle (newspaper) 0 Classified Advertising Department 1729 Briarcrest Drive P.O. Box 3000 Bryan, TX 77802 Total Recruitment Source for Navasota TX Announcer ( 1) Interviewees Positions hired from this Position from this source source The Eagle (newspaper) 1 Classified Advertising Department 1729 Briarcrest Drive P.O. -

Attachment B - Second Adjacent Waiver Requests FCC 14-211

Attachment B - Second Adjacent Waiver Requests FCC 14-211 # Group # File No. BNPL City State Applicant Name 2nd waiver station(s) 1 2 20131112ALD BIRMINGHAM AL CALVARY OF BIRMINGHAM WDJC-FM 2 2 20131113BUA BIRMINGHAM AL GREATER BIRMINGHAM MINISTRIES, INC. WDJC-FM 3 2 20131112BVI BIRMINGHAM AL LOVE COMMANDMENT MINISTRIES WDJC-FM 4 2 20131024ANR BIRMINGHAM AL THE CHURCH IN BIRMINGHAM CORPORATION WDJC-FM 5 6 10 20131112AIY FORT SMITH AR IGLESIA GOZO DE MI ALMA KTCS-FM, KLSZ-FM 7 10 20131114BDO FORT SMITH AR THE HOLY FAMILY EDUCATIONAL ASSOCIATION OFKTCS-FM, SEBASTIAN KLSZ-FM COUNTY 8 9 91 20131112AMG ORLANDO FL HAITIAN RELIEF RADIO AND COMMUNITY SERVICES,WRUM(FM) INC. 10 11 94 20131106ASJ OAKLAND PARK FL THE OMEGA CHURCH INTERNATIONAL MINISTRY WLYF(FM) 12 13 96 20131114BLS FORT LAUDERDALE FL GENESIS CENTER FOR GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT,WEDR(FM), INC. WKIS(FM) 14 96 20131113AEU HALLANDALE FL THE TRUTH WILL SET YOU FREE INC. WEDR(FM), WKIS(FM) 15 96 20131029AHM HIALEAH GARDENS FL IGLESIA MISIONERA PREGONEROS DE JUSTICIA DEWEDR(FM), FLORIDA, INC. WKIS(FM) 16 96 20131113BSY MIAMI SHORES FL BARRY UNIVERSITY WEDR(FM), WKIS(FM) 17 18 100 20131104AAW MIAMI FL SACRED FARM MINISTRIES WEDR(FM), WRTO-FM 19 20 102 20131105AJQ KISSIMMEE FL OSCEOLA CHRISTIAN PREPARATORY SCHOOL LLCWWKA(FM) 21 22 105 20131113BIO MIAMI FL 1MIAMI, INC. WFEZ(FM), WCMQ-FM 23 105 20131106ALS MIAMI FL TABERNACLE OF GLORY COMMUNITY CENTER INC.WFEZ(FM), WCMQ-FM 24 105 20131114BCD MIAMI BEACH FL CALVARY CHAPEL OF MIAMI BEACH, INC. WFEZ(FM), WCMQ-FM 25 105 20131113BUT NORTH MIAMI FL ACTION FOR BETTER FUTURE WFEZ(FM), WCMQ-FM 26 27 109 20131107ANM DANIA FL SOUTH FLORIDA FM INC. -

Manheim and Autotrader.Com Going Strong

for SpringSpring 20122012 2the road MANHEIMM AND AUTOTRADER.COM GOING STRONG PLUS:PLUS: PoliticalPolitical AdsAds inin anan ElectionElection YearYear Know Your Numbers New LightLight on EnergyEnergy CConservationonservation ForFor AllAll CoxCox Employees andand FamiliesFamilies Cox Enterprises, Inc.Inc. | Cox Communications, Inc. | ManheimManheim | CoxCox Media GroupGroup | AutoTrader.comAutoTrader.com InSide Cox — Spring 2012 4 Manheim and AutoTrader.com are driving growth through innovation and service. Editor Jay Croft Contributors Teresa Crowder Melanie Harris Loraine Fick Kimberly Hoch Andrew Flick Christina Setser Deborah Geering Carole Siracusa Photographers Bob Andres Jenni Girtman Design and Production Cristin Bowman laughingfig.com Contact InSide Cox Cox Enterprises, Inc. Corporate Communications P.O. Box 105357 Atlanta, GA 30348 Email: [email protected] Web: insite.coxenterprises.com Phone: 678-645-4744 InSide Cox is published by Cox Enterprises, Inc., for our employees, families and friends. Your feed- back is highly valued. Please send your questions, comments and suggestions to InSide Cox. Follow Cox Enterprises, Inc., on Facebook and Twitter. You are here. You make it work every day. 25 Cox Conserves Cox locations switch to energy- effi cient lighting, plus a map of sustainability efforts across the country. Contents On the Cover Our car companies are on the road to even better for ways to connect customers with cars. 2the Photo: John Kelly/Getty Images road MANHEIMMANHEIM ANDAND AUTOTRADER.COMAUTOTRADER COM GOING STRONG 2 Dialogue Letter from Jimmy Hayes and more. 17 In Business Cox Business helps the “American Idol” show go on; Cox Media Group invests in digital content production; Cox Digital Solutions and Yahoo! team up on political ads and more. -

Manheim's 20 Annual Used Car Market Report Sees Growth

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Lois Rossi Jan. 23, 2015 Sr. Director, Public Relations P: 678.645.2028 email: [email protected] MANHEIM’S 20TH ANNUAL USED CAR MARKET REPORT SEES GROWTH, STABILITY AS KEY DRIVERS OF ROBUST USED VEHICLE MARKET IN 2014 Special Anniversary Edition Marks Two Decades of Industry Thought-Leadership SAN FRANCISCO – Jan. 23, 2015 – Growth in wholesale volumes, new and used vehicle sales, and stability in wholesale pricing, were among the highlights of another strong year in the automotive markets, according to trends identified in Manheim’s annual Used Car Market Report. The Report was released today at the National Automobile Dealers Association convention. “While last year was a banner year for growth and stability in the used vehicle market, we anticipate that we’ll see the sixth consecutive year of increased new vehicle sales in 2015,” said Cox Automotive Chief Economist Tom Webb. “These sales increases will drive auction volumes higher for many years to come. This, plus the increased importance of the used vehicle market, will reinforce remarketing’s critical link in the automotive ecosystem.” This year’s Report marks a milestone in Manheim’s commitment to industry thought- leadership – the 20th edition of its annual review of data and trends shaping the used car business. “The Report provides us the opportunity to reflect on the developments that have positioned us where we are as an industry, and to look ahead at the forces that will shape the wholesale vehicle business of tomorrow,” said Manheim North America President Janet Barnard in the Report’s introductory letter. -

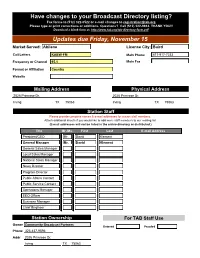

TAB Records-Stations (TABSERVER08)

Have changes to your Broadcast Directory listing? Fax forms to (512) 322-0522 or e-mail changes to [email protected] Please type or print corrections or additions. Questions? Call (512) 322-9944. THANK YOU!! Download a blank form at: http://www.tab.org/tab-directory-form.pdf Updates due Friday, November 15 Market Served: Abilene License City: Baird Call Letters KABW-FM Main Phone 817-917-7233 Frequency or Channel 95.1 Main Fax Format or Affiliation Country Website Mailing Address Physical Address 2026 Primrose Dr. 2026 Primrose Dr. Irving TX 75063 Irving TX 75063 Station Staff Please provide complete names & e-mail addresses for station staff members. Attach additional sheets if you would like to add more staff members to our mailing list. (E-mail addresses will not be listed in the online directory or distributed.) Title Mr./Ms. First Last E-mail Address President/CEO Mr. David Klement General Manager Mr. David Klement General Sales Manager Local Sales Manager National Sales Manager News Director Program Director Public Affairs Contact Public Service Contact Operations Manager EEO Officer Business Manager Chief Engineer Station Ownership For TAB Staff Use Owner Community Broadcast Partners Entered Proofed Phone 325-437-9596 Addr 2026 Primrose Dr. Irving TX 75063 Have changes to your Broadcast Directory listing? Fax forms to (512) 322-0522 or e-mail changes to [email protected] Please type or print corrections or additions. Questions? Call (512) 322-9944. THANK YOU!! Download a blank form at: http://www.tab.org/tab-directory-form.pdf Updates due Friday, November 15 Market Served: Abilene License City: Abilene Call Letters KACU-FM Main Phone 325-674-2441 Frequency or Channel 89.7 Main Fax 325-674-2417 Format or Affiliation Soft AC, News (NPR) Website www.kacu.org Mailing Address Physical Address ACU Station 1600 Campus Court Abilene TX 79699-7820 Abilene TX 79601 Station Staff Please provide complete names & e-mail addresses for station staff members. -

List of Radio Stations in Texas

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia List of radio stations in Texas From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page The following is a list of FCC-licensed AM and FM radio stations in the U.S. state of Texas, which Contents can be sorted by their call signs, broadcast frequencies, cities of license, licensees, or Featured content programming formats. Current events Random article Contents [hide] Donate to Wikipedia 1 List of radio stations Wikipedia store 2 Defunct 3 See also Interaction 4 References Help 5 Bibliography About Wikipedia Community portal 6 External links Recent changes 7 Images Contact page Tools List of radio stations [edit] What links here This list is complete and up to date as of March 18, 2019. Related changes Upload file Call Special pages Frequency City of License[1][2] Licensee Format[3] sign open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com sign Permanent link Page information DJRD Broadcasting, KAAM 770 AM Garland Christian Talk/Brokered Wikidata item LLC Cite this page Aleluya Print/export KABA 90.3 FM Louise Broadcasting Spanish Religious Create a book Network Download as PDF Community Printable version New Country/Texas Red KABW 95.1 FM Baird Broadcast Partners Dirt In other projects LLC Wikimedia Commons KACB- Saint Mary's 96.9 FM College Station Catholic LP Catholic Church Languages Add links Alvin Community KACC 89.7 FM Alvin Album-oriented rock College KACD- Midland Christian 94.1 FM Midland Spanish Religious LP Fellowship, Inc. -

Randy Rogers Band Is #1 This Week! "Drinking Money" Tommy Jackson / Thirty Tigers

RANDY ROGERS BAND Randy Rogers Band is #1 this week! "Drinking Money" Tommy Jackson / Thirty Tigers Dear Readers, RANDY ROGERS BAND is #1 this week with "Drinking Money." DARRIN MORRIS BAND's "I Will" is this week's Most Added! HOLLY Tucker's "Rhythm Of You" is the Greatest Spin Gainer! MASON LIVELY's "Something 'Bout A Southern Girl" is the top Surging & Emerging track to keep an eye on! Great work everyone! The following stations are frozen for this week. KSTV-FM (Dublin, TX) KTTU-FM HD4 (K226CH-FX) (Lubbock, TX) For those who don’t use CDX to distribute their new music but wish to be monitored by TRACtion TX, you can now go to our upload center, fill out the necessary information and send your MP3s for fingerprinting here:https://www.cdxcd.com/fingerprinting-upload-center/ . Lastly, this is our final weekly chart of the year! We will have the year end chart on December 18th and will be coming back next year with our first chart on January 6th! Have a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year! The TRACtion Texas weekly newsletter is published on Tues. evenings by CDX Nashville LLC — Connecting the music industry Stay tuned, with Texas Red Dirt radio. For more Joe Kelly information call 615-292-0123 or email President Joe Kelly- CDX President [email protected] [email protected] WWW.TRACTIONTX.COM Monitored Radio Airplay Vol 5. #49 Dec 16th, 2020 L T Wks On Spins + Stations Adds W W - Chart Artist / Song Title / Label 2 1 RANDY ROGERS BAND/Drinking Money/Tommy Jackson/Thirty Tigers 841 9 47 0 10 1 2 JON WOLFE/Heart to Steal Tonight/Fool -

Waco, TX (United States) FM Radio Travel DX

Waco, TX (United States) FM Radio Travel DX Log Updated 4/18/2015 Click here to view corresponding RDS/HD Radio screenshots from this log http://fmradiodx.wordpress.com/ Freq Calls City of License State Country Date Time Prop Miles ERP HD RDS Audio Information 88.1 KVLW Gatesville TX USA 4/12/2015 11:45 AM Tr 21 16,500 "K-Love" - ccm 88.5 KVLT Temple TX USA 4/12/2015 12:12 PM Tr 50 5,000 88.9 KSUR Mart TX USA 4/12/2015 12:12 PM Tr 16 100,000 "AFR" - ccm 89.9 KBDE Temple TX USA 4/12/2015 12:13 PM Tr 25 11,500 religious 90.1 KERA Dallas TX USA 4/12/2015 12:13 PM Tr 7 100,000 "KERA" - public radio 90.9 KCBI Dallas TX USA 4/12/2015 12:13 PM Tr 68 100,000 RDS "KCBI Radio Network" - ccm 91.3 KNCT Killeen TX USA 4/12/2015 12:14 PM Tr 50 50,000 HD RDS easy listening 91.7 KKXT Dallas TX USA 4/12/2015 12:14 PM Tr 70 100,000 RDS "KXT" - AAA 92.1 KTFW-FM Glen Rose TX USA 4/12/2015 12:14 PM Tr 70 25,000 RDS "92.1 Hank FM" - country 92.3 KIIZ-FM Killeen TX USA 4/12/2015 1:08 PM Tr 30 6,000 "Z92.3" - urban 92.5 KZPS Dallas TX USA 4/12/2015 12:15 PM Tr 35 100,000 HD "Lone Star 92.5" - classic rock 92.9 KRMX Marlin TX USA 4/12/2015 12:16 PM Tr 12 50,000 RDS "92.9 Shooter FM" - country 93.3 KGSR Cedar Park TX USA 4/12/2015 12:16 PM Tr 77 100,000 RDS "93.3 KGSR" - AAA 93.7 KNOR Krum TX USA 4/12/2015 12:16 PM Tr 132 55,000 RDS "La Raza 93.7" - spanish 94.1 KLNO Ft. -

Katrina Reply Comments FINAL

BEFORE THE FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Recommendations of the Independent ) Panel Reviewing the Impact of ) EB Docket No. 06-119 Hurricane Katrina on ) Communications Networks ) TO: The Commission REPLY COMMENTS OF COX ENTERPRISES, INC. Alexandra M. Wilson Scott S. Patrick Vice President of Public Policy Jason E. Rademacher Cox Enterprises, Inc. 1225 19th Street, NW Its Attorneys Suite 450 Washington D.C. 20036-2458 DOW LOHNES PLLC 1200 New Hampshire Avenue, N.W. Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 (202) 776-2000 (phone) (202) 776-2222 (fax) August 21, 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY........................................................................................... 1 I. A STRONG PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP IS CRITICAL TO EFFECTIVE EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS AND DISASTER RECOVERY. ............................... 3 II. THE PRIVATE SECTOR MUST CONTINUE TO TAKE A LEADERSHIP ROLE IN PLANNING FOR AND RESPONDING TO EMERGENCIES. ....................................... 5 A. Cox’s Employees Are the Foundation of the Company’s Disaster Response. ............. 5 B. Cox Maintains a Company-Wide Commitment to Disaster Preparedness. .................. 6 C. Cox’s Business Continuity Plans Performed Exceptionally Well in the Aftermath of Last Year’s Hurricanes.................................................................................................. 7 -

EEO Public File Report for April 1, 2014-March 31, 2015

EEO Public File Report for April 1, 2014-March 31, 2015 The purpose of this EEO Public File Report (“Report”) is to comply with Section 73.2080(c)(6) of the FCC’s 2002 EEO Rule. This Report has been prepared on behalf of the Station Employment Unit that is comprised of the following stations: Call Sign Community FIN WTAW College Station, TX 87145 KZNE College Station, TX 07632 KNDE College Station, TX 07631 KWBC Navasota, TX 40912 KAGC Bryan, TX 16983 KPWJ Kurten, TX 166036 KVMK Wheelock, TX 189519 A: Full Time Vacancies filled during the past year Job Title Date filled Source of hire Persons interviewed Salesperson 3/2015 Walk-in 4 Midday Announcer 10/2014 All-Access 10 Morning Announcer 8/2014 The Eagle 3 B: Recruitment Referral Sources Used to Seek Candidates for Each Position Recruitment Source for Sales Position Interviewees Positions hired from this from this source source All Access 0 All Access Music Group 28955 Pacific Coast Highway Malibu, CA 90265 On Air/Station Website 0 Ben Downs Bryan Broadcasting Box 3248 Bryan, TX 77805 979 695 9595 Aggieland Help Wanted 2 One Civic Center Plaza, Suite 506 Poughkeepsie, NY 12601 The Eagle (newspaper) 1 Classified Advertising Department 1729 Briarcrest Drive P.O. Box 3000 Bryan, TX 77802 Texas Association of Broadcasters 0 502 East 11th Street, Suite 200 Austin, TX 78701 Walk In – Staff Recruitment 1 salesperson Total 4 Recruitment Source for Midday Announcer Position Interviewees Positions hired from this from this source source All Access 9 Midday Announcer All Access Music Group 28955 Pacific Coast Highway Malibu, CA 90265 On Air/Station Website 0 Ben Downs Bryan Broadcasting Box 3248 Bryan, TX 77805 979 695 9595 Aggieland Help Wanted 0 One Civic Center Plaza, Suite 506 Poughkeepsie, NY 12601 The Eagle (newspaper) 0 Classified Advertising Department 1729 Briarcrest Drive P.O. -

National Association of Broadcasters' Memorandum in Opposition To

PUBLIC VERSION Before the ~~Qggyy UNITED STATES COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Library of Congress c, Washington, D.C. ~P~& Ply~ ) In re ) ) DETERMINATION OF ROYALTY ) DOCKET NO. 14-CRB-0001-WR RATES AND TERMS FOR ) (2016-2020) EPHEMERAL RECORDING AND ) DIGITAL PERFORMANCE OF SOUND ) RECORDINGS (WEB Ig ) ) ) NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF IN OPPOSITION TOBROADCASTERS'EMORANDUM MOTION TO COMPEL Before the UNITED STATES COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Library of Congress Washington, D.C. ) In re ) ) DETERMINATION OF ROYALTY ) DOCKET NO. 14-CRB-0001-WR RATES AND TERMS FOR ) (2016-2020) EPHEMERAL RECORDING AND ) DIGITAL PERFORMANCE OF SOUND ) RECORDINGS (8'EB IV) ) ) ) NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF IN OPPOSITION TOBROADCASTERS'EMORANDUM MOTION TO COMPEL INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY The Motion to Compel filed by SoundExchange, Inc. against the National Association of Broadcasters ("NAB") on December 1, 2014 ("Motion") is improper and should be denied. SoundExchange's motion seeks detailed financial information for the period 2011-2014 from the companies of four of the six NAB radio broadcaster witnesses. In support of its motion, SoundExchange represents that "NAB has refused to produce documents relating to its Motion at 1, and "NAB expressly refused to produce any documents concerningmembers'inances," or relating to revenues earned by NAB members that are derived from streaming." Motion at 4 (emphasis in original). Those representations are false. Two NAB fact witnesses, John Dimick ofLincoln Financial Media Corp. ("LFMC") and Ben Downs of Bryan Broadcasting, discussed their respective companies'inances, including their streaming revenues and expenses. As SoundExchange is well aware, NAB produced substantial financial information for both ofthese companies, including statements showing revenues and expenses related to streamiing and radio 'broadcasting.'nd, as to these two companies, the additional information now demanded by~ SoundExchange is simply not directly related to the testimony., as SoundExchange's strained explanations (or lack of explanation) demonstrate. -

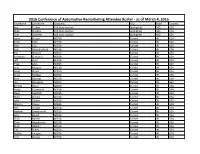

2016 Conference of Automotive Remarketing Attendee Roster

2016 Conference of Automotive Remarketing Attendee Roster - as of March 4, 2016 First Name Last Name Company City State Country Ace Tetlow 166 Auto Auction Springfield MO USA Mike Bradley 166 Auto Auction Springfield MO USA Tom Schaefer 166 Auto Auction Springfield MO USA Jason Ferreri ADESA Carmel IN USA Peter Kelly ADESA Carmel IN USA Paul Lips ADESA Carmel IN USA Bob Rauschenberg ADESA Carmel IN USA Pat Stevens ADESA Carmel IN USA Stephane St-Hilaire ADESA Carmel IN USA Jeff Hoyt ADESA Carmel IN USA Theo Jelks ADESA Carmel IN USA Jane Morgan ADESA Carmel IN USA Doug Shore ADESA Carmel IN USA Vince McNeal ADESA Carmel IN USA Kurt Madvig ADESA Carmel IN USA Jim Randazzo ADESA Carmel IN USA Brenda Moya ADESA Carmel IN USA Becky Doemland ADESA Carmel IN USA Dave Diedrich ADESA Carmel IN USA Mike Dennis ADESA Carmel IN USA John Combs ADESA Carmel IN USA Warren Clauss ADESA Carmel IN USA Rick Griskie ADESA Carmel IN USA Heather Greenawald ADESA Carmel IN USA Amy Bouck ADESA Carmel IN USA Chris Barrett ADESA Carmel IN USA Chris Angelicchio ADESA Carmel IN USA Matt Abshire ADESA Carmel IN USA Tim Finley ADESA Carmel IN USA Debbie Vaughn ADESA Carmel IN USA Tom Kontos ADESA Carmel IN USA Trevor Henderson ADESA Canada Carmel IN USA Kenny Osborn ADESA Dallas Hutchins TX USA Steve Brown AFC Carmel IN USA Joe Keadle AFC Carmel IN USA Chad Bailey Akron Auto Auction Akron OH USA Randy Linsted Akron Auto Auction Akron OH USA Mike Waseity Akron Auto Auction Akron OH USA Nancy Brooks Albany Auto Auction Albany GA USA Eric Lyman ALG Santa Monica CA USA