Ariana Pughe 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Artists Professional

CREATIVE PALESTINIAN ART COMPETITION | PUBLICATION | EXHIBITION THE ART SAWA AWARDS “This initiative is a very important one. Palestinian artists in the diaspora have participated in the growth of the Middle East art scene, but that Under the patronage of H.E Sheikh Nahyan Bin Mubarak Al Nahya, Minister of Higher Education and Scientific Research, and in partnership with the opportunity has so far been denied those living in the West Bank and Gaza. By bringing together such a number of artists and by engaging them in the Welfare Association, Art Sawa presents a juried, non-for-profit competition. The exhibition showcases contemporary art from Palestine, where 45 regional scene this competition has provided them a platform. established artists and 11 emerging artists participate, in hope to win – where there will be three winners in total. The selection is diverse. You will find among the works pathos, anger, humour, hope and, most importantly, potential. I was delighted by the range and The members of the jury consist of; Zaki Nusseibeh, Advisor at the Presidential Court and interpreter for the President of the United Arab Emirates; creativity of these artists in what, for most of them, is their first international exhibition.” William Laurie, Head of Sale at Christie’s Dubai and charge of the department of Modern and Contemporary Arab & Iranian Art worldwide; Ali Khadra, founder and publisher of Canvas Omar Donia, co-founder and publisher of Contemporary Practices Journal; Massimiliano Lodi, Manager for TDIC Cultural MR WILLIAM LAURIE Department. During this past year, there has been a multitude of events for contemporary arts from Palestine and the Diaspora, proving to be one of the Head of Sale at Christie’s Dubai and Head of Modern and Contemporary Arab & Iranian Art worldwide. -

Full Bibliography (From Sheikhs to Sultanism)

FULL BIBLIOGRAPHY (FROM SHEIKHS TO SULTANISM) Academic sources (books, chapters, and journal articles) P. Aarts and C. Roelants, Saudi Arabia: A Kingdom in Peril (London: Hurst & Co., 2015) A. Abdulla, The Gulf Moment in Contemporary Arab History (Beirut: Dar Al-Farabi, 2018) [in Arabic] I. Abed and P. Hellyer (eds.), United Arab Emirates: A New Perspective (Dubai: Trident, 2001) P. Abel and S. Horák, ‘A tale of two presidents: personality cult and symbolic nation-building in Turkmenistan’ in Nationalities Papers, Vol. 43, No. 3, 2015 A. Abrahams and A. Leber, ‘Framing a murder: Twitter influencers and the Jamal Khashoggi incident' in Mediterranean Politics [April 2020 online first view] D. Acemoglu, T. Verdier, and J. Robinson, ‘Kleptocracy and Divide-and-Rule: A Model of Personal Rule’ in Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 2, Nos. 2-3, 2004 G. Achcar, The People Want: A Radical Exploration of the Arab Uprising (London: Saqi, 2013) A. Adib-Moghaddam (ed.), A Critical Introduction to Khomeini (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014) I. Ahyat, ‘Politics and Economy of Banjarmasin Sultanate in the Period of Expansion of the Netherlands East Indies Government in Indonesia, 1826-1860’ in Tawarikh: International Journal for Historical Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2, 2012 A. Al-Affendi, ‘A Trans-Islamic Revolution?’, Critical Muslim, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2012 M. Al-Atawneh, ‘Is Saudi Arabia a Theocracy? Religion and Governance in Contemporary Saudi Arabia’ in Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 45, No. 5, 2009 H. Albrecht and O. Schlumberger, ‘Waiting for Godot: Regime Change Without Democratization in the Middle East’ in International Political Science Review, Vol. -

Sir Bani Yas Desert Island – Al Ain – Fujairah - Dubai 4 – 14 December 2017

United Arab Emirates: Gardens, wetlands, and wildlife Abu Dhabi – Sir Bani Yas Desert Island – Al Ain – Fujairah - Dubai 4 – 14 December 2017 December 4 Abu Dhabi ( D ) Hotel: Royal Rose Hotel Upon your arrival at Abu Dhabi International Airport, you will be greeted and transferred to the Royal Rose Hotel. For individuals arriving early and wishing to explore, the hotel is conveniently located downtown and is within walking distance of the Corniche. Welcome dinner at a gourmet restaurant. December 5 Al Wathba Wetland Reserve / Mangrove National Park ( B, L, D ) Hotel: Royal Rose Hotel We will begin our morning with breakfast at the hotel and then head out for a hike at the Al Wathba Wetland Reserve. Known for its stunningly large flamingo population, the reserve is composed of both natural and man-made bodies of water. The reserve serves as home for several endangered species and is home for 37 plant species and over 250 different species of birds. After our hike we will enjoy a relaxing lunch and then give our legs a chance to rest a bit as we board boats for a several hour exploration of Mangrove National Park. Protected by government order, Mangrove National Park is a dense concentration of mangrove trees in Abu Dhabi and serves as home for several hundred marine animals and birds. Upon return to the hotel we will have time to rest a bit before dinner. December 6 Sheikh Zayed Mosque / Abu Dhabi Falcon Hospital / Emirates Palace ( B, T, D ) Hotel: Emirates Palace We will meet for breakfast at the hotel and then head to the beautiful Sheikh Zayed Mosque. -

The Pulse of Trade HANDLING the WORLD BIGGEST SHIPS Section 2 CSP ABU DHABI TERMINAL 36 KAMSAR CONTAINER TERMINAL 56

The Pulse of Trade HANDLING THE WORLD BIGGEST SHIPS Section 2 CSP ABU DHABI TERMINAL 36 KAMSAR CONTAINER TERMINAL 56 TABLE OF THE ABU DHABI ADVANTAGE 14 ZAYED PORT AND THE FREE PORTS 36 KHALIFA PORT FTZ 58 SAFE, STABLE AND COSMOPOLITAN 16 MUSAFFAH PORT AND THE NEW MUSAFFAH 38 Section 4 CHANNEL CONTENTS GLOBAL MARKETS WITHIN REACH 18 SUSTAINABILITY 60 A REGION ON THE MOVE 20 SHAHAMA PORT 39 BENEFITING THE BUSINESS, ENVIRONMENT AND 62 COMMUNITY THE WESTERN REGION PORTS 41 CEO WELCOME 04 Section 3 COMMERCIAL 64 INFRASTRUCTURE THAT PERFORMS 22 FUJAIRAH TERMINALS 42 ENVIRONMENT 66 CUTTING-EDGE, EFFICIENT AND CUSTOMER-FOCUSSED 24 ABU DHABI PORTS MARINE SERVICES “SAFEEN” 44 Section 1 COMMUNITY 68 INTRODUCTION 06 KHALIFA PORT 26 ABU DHABI PORTS MARITIME TRAINING CENTRE 46 AWARDS AND RECOGNITIONS 70 ENABLING ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND TRADE 08 EXPANSION PLANS AT KHALIFA PORT 30 ABU DHABI CRUISE TERMINAL 48 DIVERSIFYING THE EMIRATE’S ECONOMY 10 KHALIFA INDUSTRIAL ZONE ABU DHABI (KIZAD) 32 SIR BANI YAS CRUISE BEACH 50 HELPING BUSINESSES THRIVE 12 KHALIFA PORT FREE TRADE ZONE 34 THE MAQTA GATEWAY 52 ABU DHABI TERMINALS (ADT) CEO WELCOME CEO WELCOME TO ABU DHABI PORTS HELPING CUSTOMERS AND COMMUNITIES THRIVE Abu Dhabi Ports operates in highly competitive, capital-intensive, and fishing and leisure ports play a central role in the daily lives of those globally connected industries. As a business enabler, we are focused people living in the surrounding villages and towns. on delivering value to our investors and customers. We work to help them thrive. We help people make goods, and move those goods In the Western Region, our ports are serving as transit points for around the world. -

List of Hospital Providers Within UAE for Daman's Health Insurance Plans

List of Hospital Providers within UAE for Daman ’s Health Insurance Plans (InsertDaman TitleProvider Here) Network - List of Hospitals within UAE for Daman’s Health Insurance Plans This document lists out the Hospitals available in the Network for Daman’s Health Insurance Plan (including Essential Benefits Plan, Classic, Care, Secure, Core, Select, Enhanced, Premier and CoGenio Plan) members. Daman also covers its members for other inpatient and outpatient services in its network of Health Service Providers (including pharmacies, polyclinics, diagnostic centers, etc.) For more details on the other health service providers, please refer to the Provider Network Directory of your plan on our website www.damanhealth.ae or call us on the toll free number mentioned on your Daman Card. Edition: October 01, 2015 Exclusive 1 covers CoGenio, Premier, Premier DNE, Enhanced Platinum Plus, Enhanced Platinum, Select Platinum Plus, Select Platinum, Care Platinum DNE, Enhanced Gold Plus, Enhanced Gold, Select Gold Plus, Select Gold, Care Gold DNE Plans Comprehensive 2 covers Enhanced Silver Plus, Select Silver Plus, Enhanced Silver, Select Silver Plans Comprehensive 3 covers Enhanced Bronze, Select Bronze Plans Standard 2 covers Care Silver DNE Plan Standard 3 covers Care Bronze DNE Plan Essential 5 covers Core Silver, Secure Silver, Core Silver R, Secure Silver R, Core Bronze, Secure Bronze, Care Chrome DNE, Classic Chrome, Classic Bronze Plans 06 covers Classic Bronze and Classic Chrome Plans, within Emirate of Dubai and Northern Emirates 08 -

United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates Offices Above Dubai Hamriyah Free Zone Dubai Aldar HQ Building Abu Dhabi Abu Dhabi Investment Council Headquarters Abu Dhabi Aldar HQ Building Abu Dhabi Armada Tower, Jumeirah Lake Towers Dubai Civil Defence Building, Al Manara & Tecom Dubai D1 Tower Dubai Dubai Bank Jumeirah Branch Dubai Dubai Investment Park Dubai Etihad Towers Abu Dhabi Finance House Head Office Bldg. Abu Dhabi Kobian Gulf, Jafza Dubai Silver Tower, Business Bay Dubai Hospitals & Medical Centres Arzanah Medical Complex Abu Dhabi Emirates Franco Hospital Abu Dhabi Lifecare Hospital Abu Dhabi Mafraq Hospital Abu Dhabi Education Al Mutawa School Abu Dhabi P.I. School Accommodation Abu Dhabi Sas Al Nakhl High School Accommodation Abu Dhabi Zayed University Campus Abu Dhabi www.rapidrop.com United Arab Emirates Hotels Above Al Zorah Resort Ajman Hyatt Regency, Conrad Hotel Abu Dhabi Dubai Greek Heights, Dubai Emirates Pearl Hotel Abu Dhabi Hyatt Regency , Dubai Greek Heights Dubai Jumeirah Al Khor Hotel Apartments Dubai Lemeridien Airport Hotel Dubai Bloom Central - Marriot Abu Dhabi JW Mariott Marquis Dubai Entertainment Al Rayyana Golf Garden Dubai Dubai Safari Dubai Golf Garden Abu Dhabi Meydan Racing District Development Dubai Motion Gate Theme Park Dubai Wadi Adventure Al Ain Yas Island - Ferrari Experience Abu Dhabi Zayed Sports City Abu Dhabi www.rapidrop.com United Arab Emirates Retail & Shopping Malls Above Mirdif City Centre, Dubai Digital Systems, Jafza Dubai Adidas Factory Outlet Dubai Pizza Hut, Al Ghurair City Abu Dhabi Bath & Body Works, -

International Offering Memorandum

IMPORTANT: You must read the following disclaimer before continuing. The following disclaimer applies to the attached offering memorandum (the ‘‘document’’) and you are therefore advised to read this carefully before accessing, reading or making any other use of the attached document. In accessing the document, you agree to be bound by the following terms and conditions, including any modifications to them from time to time, each time you receive any information from us as a result of such access. You acknowledge that this electronic transmission and the delivery of the attached document is confidential and intended only for you and you agree you will not forward, reproduce, copy, download or publish this electronic transmission or the attached document (electronically or otherwise) to any other person. ANY FORWARDING, REDISTRIBUTION OR REPRODUCTION OF THE DOCUMENT IN WHOLE OR IN PART IS UNAUTHORISED. FAILURE TO COMPLY WITH THIS DIRECTIVE MAY RESULT IN A VIOLATION OF THE UNITED STATES SECURITIES ACT OF 1933, AS AMENDED (THE ‘‘SECURITIES ACT’’), OR THE APPLICABLE LAWS OF OTHER JURISDICTIONS. NOTHING IN THIS ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES AN OFFER OF SECURITIES FOR SALE IN THE UNITED STATES OR ANY OTHER JURISDICTION WHERE IT IS UNLAWFUL TO DO SO. THE SECURITIES HAVE NOT BEEN AND WILL NOT BE REGISTERED UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT OR WITH ANY SECURITIES REGULATORY AUTHORITY OF ANY STATE OR OTHER JURISDICTION OF THE UNITED STATES AND, SUBJECT TO CERTAIN EXCEPTIONS, MAY NOT BE OFFERED, SOLD, PLEDGED OR OTHERWISE TRANSFERRED IN THE UNITED STATES. Confirmation of your representation: By accepting electronic delivery of this document, you are deemed to have represented to Citigroup Global Markets Limited, First Abu Dhabi Bank PJSC, HSBC Bank Middle East Limited and Merrill Lynch International (collectively, the ‘‘Joint Global Coordinators’’), EFG Hermes UAE Limited, EFG Hermes Promoting & Underwriting (solely in its capacity as underwriter), Goldman Sachs International and Morgan Stanley & Co. -

Field Trip Engineering Features of the Limestone Bedrocks of Al-Ain, Uae

15–18 November ❙ Al Ain, UAE WWW.SEG.ORG/ICEG15 FIELD TRIP ENGINEERING FEATURES OF THE LIMESTONE BEDROCKS OF AL-AIN, UAE N Al-Ain 0 3 1 4 U A E OMAN 0 5 10 15 Kilometers Date of the field tour:Thursday 19th November, 2015 Time: 8:30 a.m. – 3 p.m Place of Departure:. El Maqam University Campus, Crescent Building Aspects of the tour: Karstic cavities are common structural features in the limestone basement rocks of Abu Dhabi Emirate, especially in the Dammam and the overlying Asmari Formations in Al-Ain city. These cavities constitute hazards for the stability of building foundations. This tour will visit areas affected by karstic cavitation and also other more recent features of bedrock weathering. Tour guides: Professor Hasan Arman, Dr. Abdel-Rahman Fowler and Dr. Osman Abdelghany Field tour: Al-Ain Area, Jabal Mundassa, Jabal Hafit Lunch arrangements: 1:30–2:30 p.m. at the Mercure Hotel, Summit of Jabal Hafit. SEG.ORG/ICEG15 TOUR ITINERARY Stop 1 At Jabal Mundassa we will examine the coarse-grained fossiliferous bioclastic limestones of the Upper Cretaceous Simsima Formation, which have intensely developed fracturing described as stylolitic (dissolution along cracks by stress-increased solubility), veining (calcite healed opened cracks) and faults. Diversity of fractures in the Simsima Formation at Jabal Mundassa SEG.ORG/ICEG15 Stop 2 Sinkholes and other karstic features of the Dammam and Asmari limestone formations will be viewed near Mazyad on the eastern side of Jabal Hafit. In addition, the limestones in this area show recent surface cavitation (honeycomb) weathering related to wind and salt effects in an arid climate. -

The Cultural Sites of Al Ain (United Arab Emirates) No 1343

Background This is a new nomination. The cultural sites of Al Ain (United Arab Emirates) Consultations ICOMOS consulted its International Scientific No 1343 Committees on Archaeological Heritage Management and on Cultural Landscapes, and several independent experts. Literature consulted (selection) Official name as proposed by the State Party The Cultural Sites of Al Ain (Hafit, Hili, Bidaa Bint Saud Al-Jabir Al-Sabah, S., Les Émirats du Golfe, histoire d'un and Oases Areas) peuple, Paris, 1980. Location Cleuziou, S., “French Archaeological Mission, 1st mission…”, Abu Dhabi Archaeology in the United Arab Émirates, vol I, 1977. Regions and districts of: Al Ain Central District, Al Jimi, Al Mutaredh, Al Mutawa’a, Al Muwaiji, Al Qattara, Bidaa Bint Cleuziou, S., et al., Essays on the late prehistory of the Arabian peninsula, Rome, 2002. Saud, Falaj Hazza, Hili, Jebel Hafit, Sanaiya and Shiab Al Ashkar Méry, S., Fine Wadi Suq Ware from Hili and Shimal Sites United Arab Emirates (United Arab Emirates): A Technological and Provenience Analysis, 1987. Brief description The various sites of Al Ain and its neighbouring region Said Al-Jahwari, N., “The agricultural basis of Umm an-Nar provide testimony to very ancient sedentary human society in the northern Oman peninsula (2500–2000 BC)”, occupation in a desert region. Occupied continuously Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy, 20-2, 2009. since the Neolithic, the region presents vestiges of Technical Evaluation Mission numerous protohistoric cultures, notably from the Bronze An ICOMOS technical evaluation mission visited the Age and the Iron Age. Very diverse in nature, these property from 11 to 16 October 2010. -

List of Pharmaceutical Providers Within UAE for Daman's Health Insurance Plans

List of Pharmaceutical Providers within UAE for Daman ’s Health Insurance Plans (InsertDaman TitleProvider Here) Network - List of Pharmaceutical Providers within UAE for Daman’s Health Insurance Plans This document lists out the Pharmacies and Hospitals available in Daman’s Network, dispensing prescribed medicines, for Daman’s Health Insurance Plan (including Essential Benefits Plan, Classic, Care, Secure, Core, Select, Enhanced, Premier and CoGenio Plan) members. Daman also covers its members for other inpatient and outpatient services in its network of Health Service Providers (including hospitals, polyclinics, diagnostic centers, etc.). For more details on the other health service providers, please refer to the Provider Network Directory of your plan on our website www.damanhealth.ae or call us on the toll free number mentioned on your Daman Card. Edition: October 01, 2015 Exclusive 1 covers CoGenio, Premier, Premier DNE, Enhanced Platinum Plus, Select Platinum Plus, Enhanced Platinum, Select Platinum, Care Platinum DNE, Enhanced Gold Plus, Select Gold Plus, Enhanced Gold, Select Gold, Care Gold DNE Plans Comprehensive 2 covers Enhanced Silver Plus, Select Silver Plus, Enhanced Silver, Select Silver Plans Comprehensive 3 covers Enhanced Bronze, Select Bronze Plans Standard 2 covers Care Silver DNE Plan Standard 3 covers Care Bronze DNE Plan Essential 5 covers Core Silver, Secure Silver, Core Silver R, Secure Silver R, Core Bronze, Secure Bronze, Care Chrome DNE, Classic Chrome, Classic Bronze Plans 06 covers Classic Bronze -

Nationalism in the Gulf States

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Research Online Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States Nationalism in the Gulf States Neil Partrick October 2009 Number 5 The Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States is a ten year multidisciplinary global programme. It focuses on topics such as globalisation, economic development, diversification of and challenges facing resource rich economies, trade relations between the Gulf States and major trading partners, energy trading, security and migration. The Programme primarily studies the six states that comprise the Gulf Cooperation Council – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. However, it also adopts a more flexible and broader conception when the interests of research require that key regional and international actors, such as Yemen, Iraq, Iran, as well as its interconnections with Russia, China and India, be considered. The Programme is hosted in LSE’s interdisciplinary Centre for the Study of Global Governance, and led by Professor David Held, co- director of the Centre. It supports post-doctoral researchers and PhD students, develops academic networks between LSE and Gulf institutions, and hosts a regular Gulf seminar series at the LSE, as well as major biennial conferences in Kuwait and London. The Programme is funded by the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences. www.lse.ac.uk/LSEKP/ Nationalism in the Gulf States Research Paper, Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States Dr Neil Partrick American University of Sharjah United Arab Emirates [email protected] Copyright © Neil Partrick 2009 The right of Neil Partrick to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

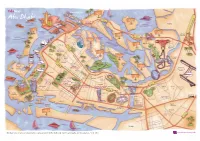

Schools Distributing Yalla This Map Is Not to Scale & Is

Guggenheim Abu Dhabi Saadiyat Zayed Island Port Louvre Abu Dhabi Al Zayed National Museum Mina Ramhan E12 Cranleigh Island Abu Dhabi Al Bahya Sheikh Khalifa Lulu Bridge Island Abu Dhabi - Dubai Road Dhow Yas Island Emirates Harbour Al Jubail Island Park Zoo Al E12 Corniche Repton School Zahiyah Abu Dhabi Al Maryah Island Yas Abu Dhabi Waterworld Mall Zeera Al Danah Island Ferrari World E10 Abu Dhabi Al Muna Primary School Al Reem Island Al Hosn Sheikh Zayed Bin Sultan St Umm Yifenah Madinat Island Yas Marina Zayed Circuit Mangrove Al Manhal Al National Park E22 Dhafrah Samaliyah Sheikh Rashid BinThe Saeed Pearl St (Airport Rd) Island Primary School Abu Dhabi Al Marina International Al Nahyan Airport Heritage Village Al Khalidiyah Sas Al Al Nakhl Al Musalla Al Etihad Zafranah Al Rayhan American Brighton Emirates Community 3. Al Mushrif School College Palace Khalifa School of Mushrif Central Park Al Bateen Park Al Yasmina Abu Dhabi Al Rehaan Secondary School British School Al Sheikh Zayed Bridge E10 School Al Rowdah American International Khalifa Al Khubeirah Al Khubairat Muntazah Masdar Al Khaleej Arabi St (30th) School of Abu Dhabi City City Khor Al E22 Royal Stables Zayed Maqta’a Al Ras Sports City Al Mushrif ADNEC Al Akhdar Al Ain Zoo Sheikh Zayed Al Maqta Bridge Cricket Stadium Umm Al Nar Al Bateen Al Maqta Coconut Al Bateen Zayed Island Boat Yard University Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque Al Musaffah Bridge Zayed City Al Hudayriat Island The British International School Abu Dhabi E11 Musaffah Schools Distributing Yalla This map is not to scale & is intended as a representation of Abu Dhabi only.