The Dark Ride

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chessington World of Adventures Guide

Chessington World of Adventures Guide Overview One of three theme parks located in Greater London that are operated by Merlin Entertainments Group, Chessington World of Adventures combines a host of rides and shows with a world-class zoo. Whereas nearby LEGOLAND Windsor is aimed at families with kids aged 2-12, and Thorpe Park caters for teens and young adults, Chessington offers something for just about every age group. In addition to the theme park and zoo, the site is also home to the Holiday Inn Chessington, a safari-themed hotel that overlooks the Wanyama Village & Reserve area. History The origins of Chessington World of Adventures can be traced back to 1931, when a new zoo was established in the grounds of a fourteenth century country mansion by entrepreneur Reginald Goddard. The zoo was eventually acquired by the Pearsons Group in 1978, which subsequently merged with the Madame Tussauds chain to form The Tussauds Group. The newly-formed company embarked on an ambitious £12 million project to build a theme park on the site, and Chessington World of Adventures opened to the public in 1987. Attractions Africa Penguins of Madagascar Live: Operation Cheezy Dibbles User rating: (3 votes) Type: Live show Opening date: Mar 23, 2012 A new Madagascar-themed show set to open in 2015 to celebrate the "Year of the Penguins" Penguins of Madagascar Mission: Treetop Hoppers User rating: (2 votes) Type: Drop tower Height: 20 feet Manufacturer: Zamperla Model: Jumpin' Star Minimum rider height: 35 inches Opening date: 2001 Penguins of Madagascar Mission: Treetop Hoppers is a child-friendly take on the classic drop tower attraction. -

ACE's Scandinavian Sojourn

ACE’s Scandinavian Sojourn : A Southerner’s Perspective Story by: Richard Bostic, assisted by Ronny Cook When I went on the ACEspana trip back in 2009, it was by far one of the most amazing vacations I have ever experienced. In addition to getting to visit parks in a different culture than we see here, it is also a great opportunity to spend time with fellow enthusiasts and grow friendships while enjoying our common interests. When Scandinavia Sojourn was announced for the summer of 2011, I knew it was a trip I could not miss. Since the 2009 trip was my first trip to Europe I thought that there was no way the over- all experience could be better in Scandinavia. I was wrong. We landed in Helsinki, Finland around 1300 the day before we were required to be at the hotel to meet with the group. Helsinki is an interesting city and fairly new compared to many cities in Europe. Walking around the city you can see the Russian influence in the city’s architecture. In fact, many movies during the cold war would use Helsinki to shoot scenes that are supposed to be set in the Soviet Union. After making our way to the Crowne Plaza Hotel and getting a quick lunch at the hotel restaurant we decided to spend the remaining time that afternoon checking out some of the sites around our hotel. Some of these sites included the Temppeliaukio Church inside of a rock formation, the train station, Routatientori Square and National Theater, and a couple of the city’s art museums. -

Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk's Carousel Turns

TM Celebrating Our 15th Year Vol. 15 • Issue 8.2 NOVEMBER 2011 Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk’s carousel turns 100 STORY: Jeffrey L. Seifert gigantic natatorium that of- [email protected] fered one of the largest heated saltwater pools ever created. SANTA CRUZ, Calif. — Other attractions soon fol- The oldest ride at the Santa lowed including a miniature Cruz Beach Boardwalk passed steam train that same year, a the century mark earlier this Thompson Scenic Railway in summer. 1908 and the Looff Carousel in Charles I.D. Looff, one of 1911. the earliest and most success- ful builders of carousels deliv- Americans fall in love ered the “Merry Go Round” come a popular pastime. with the ‘Carousel’ to the Boardwalk in August of John Leibrandt opened Though dating back to 1911. the first public bathhouse on France in the mid 16th centu- Looff, who immigrated the beach in 1865. The Santa ry, it wasn’t until the late 1800s from Denmark as a young Cruz beach, with its south- and the adaptation of a steam man, began building carousels ern shore on the north side of engine that carousels became in 1875, installing his first at Monterey Bay was protected popular. Mrs. Lucy Vanderveer’s Bath- from the harsh waves typical Americans had become ing Pavilion at Coney Island, of the west coast and offered a enchanted with these new New York City, in 1876. Be- beautiful and serene area with rides in the late 1800s and ear- The historic Santa ing one of the first, many of safe, open-water swimming. -

Editorial Rmoon the Other Day I Went Down He Wovdd Talk to Me, ‘“Cause I Didn’T to the Plaza to Look for Someone In Seem Au Uptight and Stuff

Volume 12 • Issue 2 October 2, 2007 Editorial rMOON The other day I went down he wovdd talk to me, ‘“cause I didn’t to the plaza to look for someone in seem aU uptight and stuff... I Staff teresting. I had a vague idea of find seemed like, pretty cool, and just a ing someone to interview for the guy who was tryin’ to go to school, Levi Armlovich Moon, a sort of ‘Man on the Street’ and get by and everything.” So after thing. So I went downtown, parked, an hour and a half or so of hanging Editor and started ambling toward the plaza. out Hstening to these guys play— and I saw some homeless-looking guys they really were good— I got my in Micheal Grotz hanging out, but I just didn’t get the terview. It wasn’t long. I asked Intern right vibe from them. I kept on Jessie what his story was, where he walking. When I got to San Fran was from and why he was here and Esme Gaisford cisco Street I heard music. Now, I where he was going. He told me, have always had a special place in my “I’m not really an interesting person, Layout and Design heart for street performers, especially man. I’m just a kid from the Mid musicians. I saw these three accor west who Hked to play music, and Gatlin Cass dion players once in Cologne who who wanted to hke, go some places Layout and Design were playing Beethoven... but that’s and play.” I was astonished. -

Dark Rides and the Evolution of Immersive Media

Journal of Themed Experience and Attractions Studies Volume 1 Issue 1 Article 6 January 2018 Dark rides and the evolution of immersive media Joel Zika Deakin University, [email protected] Part of the Environmental Design Commons, Interactive Arts Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/jteas University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Themed Experience and Attractions Studies by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Zika, Joel (2018) "Dark rides and the evolution of immersive media," Journal of Themed Experience and Attractions Studies: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/jteas/vol1/iss1/6 Journal of Themed Experience and Attractions Studies 1.1 (2018) 54–60 Themed Experience and Attractions Academic Symposium 2018 Dark rides and the evolution of immersive media Joel Zika* Deakin University, 221 Burwood Hwy, Burwood VIC, Melbourne, 3125, Australia Abstract The dark ride is a format of immersive media that originated in the amusement parks of the USA in the early 20th century. Whilst their numbers have decreased, classic rides from the 1930s to the 70s, such as the Ghost Train and Haunted House experiences have been referenced is films, games and novels of the digital era. Although the format is well known, it is not well defined. There are no dedicated publications on the topic and its links to other media discourses are sparsely documented. -

Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory Goes Batty with Home Run

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory Goes Batty with Home Run Halloween Museum plans ghoulish grand slam weekend; Festivities begin Wednesday Louisville, Ky. – October 12th, 2016 - For Halloween, Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory is getting wicked. Wicked fun, that is. From October 19 – 23, Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory will celebrate its first ever Home Run Halloween. A hauntingly good time that includes Creepy Cocktails, two nights of Double Creature Features and a Family Fun Fest, plus The World’s Largest Vampire Stake and free admission to the spectacular Ripley’s Believe It or Not!® Oddball™ exhibition. Wednesday, October 19th World’s Largest Vampire Stake Unveiled Vampires beware. They don’t make your kind of bats at Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory. But they do have a big surprise for any bloodsuckers who swoop by. On Wednesday, October 19, at 10 a.m., Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory will unveil The World’s Largest Vampire Stake. The stake is a towering eight-feet, eight-inches long. It was hand-hewn in the bat factory owned by Hillerich & Bradsby Co. A chainsaw, an electric hand planer and a blow torch were used to craft the stake from a 12-inch diameter ash log that was selected and shipped in from H&B’s forest in Northwest Pennsylvania. “The same properties that make our ash trees great for baseball bats also make them the perfect choice for vampire stakes. Because of its grain structure, ash wood is flexible and less likely to break, just what you need when a baseball or a vampire is coming your way,” deadpanned Anne Jewell, VP and Executive Director of Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory. -

The Cairo Street at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893

Nabila Oulebsir et Mercedes Volait (dir.) L’Orientalisme architectural entre imaginaires et savoirs Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 István Ormos DOI: 10.4000/books.inha.4915 Publisher: Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art Place of publication: Paris Year of publication: 2009 Published on OpenEdition Books: 5 December 2017 Serie: InVisu Electronic ISBN: 9782917902820 http://books.openedition.org Electronic reference ORMOS, István. The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 In: L’Orientalisme architectural entre imaginaires et savoirs [online]. Paris: Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art, 2009 (generated 18 décembre 2020). Available on the Internet: <http://books.openedition.org/ inha/4915>. ISBN: 9782917902820. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.inha.4915. This text was automatically generated on 18 December 2020. The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 1 The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 István Ormos AUTHOR'S NOTE This paper is part of a bigger project supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA T048863). World’s fairs 1 World’s fairs made their appearance in the middle of the 19th century as the result of a development based on a tradition of medieval church fairs, displays of industrial and craft produce, and exhibitions of arts and peoples that had been popular in Britain and France. Some of these early fairs were aimed primarily at the promotion of crafts and industry. Others wanted to edify and entertain: replicas of city quarters or buildings characteristic of a city were erected thereby creating a new branch of the building industry which became known as coulisse-architecture. -

Bethesda Park: "The Handsomest Park in the United States"

THE MONTGOMERY COUNTY STORY Published Quarterly by The Montgomery County Historical Society Philip L. Cantelon Eleanor M. V. Cook President Editor Vol. 34, No. 3 August 1991 BETHESDA PARK: "THE HANDSOMEST PARK IN THE UNITED STATES" by William G. Allman If asked what late-19th century amusement park might have claimed to be "the handsomest park in the United States," first to come to mind would probably be part of the Coney Island complex or, on a more local level, perhaps Glen Echo Park or Marshall Hall. This boast, however, appeared in an 1893 newspaper advertisement for Bethesda Park, a short-lived (1891- 1896?) and rather obscure amusement facility in Montgomery County.1 In this, the centennial year of its inception, an examination of its brief history provides an interesting study of the practices of recreation and amusement in the 1890's and the role they played in suburban development. The last decade of the 19th century was the first decade of the era of the electric street railway, a major improvement in public transportation that contributed greatly to suburban development around American cities. With a significant extension of the radius of practicable commuting from the city center, developers could select land that lay beyond jurisdictional boundaries, embodied desirable topographical features, or fulfilled the "rural ideal" which was becoming increasingly attractive to urban Americans.2 The rural Bethesda District fell within such an extended commuting radius from the city of Washington, and had been skirted by the the county's first major transportational improvement - the Metropolitan Branch of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad completed in 1873. -

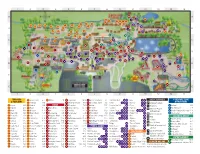

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 a B C D E F G a B C D E F G 1 2 3 4

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 A 44 A 23 37 G 28 35 36 32 31 30 29 14 16 34 33 12 22 24 1 3 4 10 11 2 5 6 13 15 43 21 9 B G B 20 7 8 17 18 3 19 4 24 27 5 6 19 25 20 21 7 C 25 C 22 23 6 12 3 4 2 45 1 2 18 28 3 6 13 16 19 30 1 G 7 17 23 2 15 31 D 2 20 25 27 D 10 29 32 3 G G G 21 G 26 5 1 8 4 12 1 33 G 34 G 1 5 G 24 G 14 1 6 G 9 22 G 13 G G 18 11 11 42 G 5 G G 8 E 4 10 35 E 9 15 G 7 40 41 16 36 14 2 G 4 F 37 F 3 39 17 38 G G 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 TERRACES 21 Group Foods 4-C 16 Willow 7-B 43 Log Flume 10-B 11 Space Scrambler 3-E Cinnamon Roll 9 21 Milk 2 9 GUEST SERVICES X-VENTURE ZONE & PAVILIONS ATTRACTIONS 34 Irontown 9-B 24 Merry-Go-Round 9-D 23 Speedway Junior 9-D Coffee 2 9 19 Nachos 10 25 Drinking Fountain 13 Aspen 6-B 12 Juniper 6-B RIDES 18 Moonraker 7-D 39 Spider 11-F Corn on the Cob 22 Pizza 4 10 Telephone 1 Catapult 2-D 9 Bighorn 4-B Maple 6-C 25 Baby Boats 9-D 36 Musik Express 14-E 22 Terroride 7-E Corndog 10 15 Popcorn 7 Strollers, Wagons 2 Top Eliminator 2-F 15 Birch 6-B 22 Meadow 3-C 12 Bat 4-C 13 OdySea 5-C 31 Tidal Wave 10-D Cotton Candy 7 9 13 Pretzel 4 10 13 21 & Wheelchairs 3 Double Thunder Raceway 3-F 7 Black Hills 3-B 31 Miners Basin 9-A 9 Boomerang 3-E 5 Paratrooper 2-E 10 Tilt-A-Whirl 3-E Dip N Dots5 7 12 18 24 Pulled Pork 22 Gifts & Souvenirs 4 Sky Coaster 4-E 17 Bonneville 5-B 24 Oak 5-C 15 Bulgy the Whale 7-D 28 Puff 9-C 32 Turn of the Century 11-D Floats 9 16 23 Ribs 22 ATM LAGOON A BEACH 10 Bridger 4-B 36 Park Valley 8-A 40 Cliffhanger 11-E 44 Rattlesnake Rapids 10-A 38 Wicked 12-G Frozen 1 11 17 -

Briefing Book and Background Data for Regional Attractions and Children's Parks

University of Central Florida STARS Harrison "Buzz" Price Papers Digital Collections 7-3-1991 Briefing Book and Background Data for Regional Attractions and Children's Parks Harrison Price Company Part of the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/buzzprice University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collections at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Harrison "Buzz" Price Papers by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Harrison Price Company, "Briefing Book and Background Data for Regional Attractions and Children's Parks" (1991). Harrison "Buzz" Price Papers. 142. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/buzzprice/142 . .. -.· ...- - ~ ·"" . ...- "" ... :-·. ... ~ ' . ..... .... - . ·. ' .. : ~ ... .. ·. ··. • ;- . ..: . ·. - . .~ .-. ... : . --~ : .. -. .- . • .... :_. ·... : ~ - ·. .. · . - . - .- .. · .· ..-. .· .. - . -- .· . .. ·• . .... ,' . ... .. · . - .. ;.· . : ... : . · -_- . ·... · .. · ··.. ' r . ........... , . - . ... ·- ·..... • ... ··· : . ' HARRISON PRICE COMPANY BRIEFING BOOK AND BACKGROUND DATA FOR REGIONAL ATTRACTIONS AND CHILDREN'S PARKS Prepared for: MCA Recreation Services Group July 3, 1991 Prepared by: Harrison Price Company 970 West 190th Street, Ste. 580 Torrance, California 90502 (213) 715-6654. FAX (213) 715-6957 REGIONAL ATTRACTIONS ESTIMATED MARKET SIZE OF CITIES WITH AND WITHOUT MAJOR PARKS (Millions) Resident -

United States District Court Northern District of Alabama Northeastern Division

Case 5:03-cv-01829-CLS Document 62 Filed 06/07/06 Page 1 of 54 FILED 2006 Jun-07 AM 09:51 U.S. DISTRICT COURT N.D. OF ALABAMA UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA NORTHEASTERN DIVISION JOHN ROMANO, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) vs. ) Civil Action No. CV-03-S-1829-NE ) CHARLES P. SWANSON, et al., ) ) Defendants. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION This diversity action, stating claims for negligence and violation of a bailment agreement allegedly resulting in severe damage to plaintiff’s rare Porsche race car, is before the court following a bench trial. PART ONE Findings of Fact1 Plaintiff, Dr. John Romano, is a resident of the State of Massachusetts and the owner of the 1970 Porsche race car, model 908/3, that is the subject of this litigation. The machine is extraordinarily rare, one of only thirteen constructed, and each hand- made. It was designed to be run in the Targa Floria race held annually on the island of Sicily. Dr. Romano purchased the Porsche (or at least its constituent parts, as the 1The following factual findings are derived from the parties’ statement of agreed facts, as well as from the evidence presented at trial. Case 5:03-cv-01829-CLS Document 62 Filed 06/07/06 Page 2 of 54 automobile was in a very incomplete state) in 1999 for $440,000. He associated Dale Miller, a North Carolina resident and consultant specializing in the restoration of historic automobiles, to coordinate the restoration work.2 By April of 2002, following two-and-a-half years of careful work by restoration specialists, the value of plaintiff’s Porsche had increased to $750,000.3 On the dates of the events leading to this suit, Mr. -

They Wish They Were Us / Jessica Goodman

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, New York First published in the United States of America by Razorbill, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2020 Copyright © 2020 by Jessica Goodman Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. RAZORBILL & colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC. Visit us online at penguinrandomhouse.com LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Names: Goodman, Jessica, 1990– author. Title: They wish they were us / Jessica Goodman. Description: New York : Razorbill, 2020. | Audience: Ages 14+. Summary: At an exclusive prep school on Long Island, Jill Newman looks forward to her senior year as a member of the school’s most elite clique, the Players, until new evidence surfaces about the murder of her close friend Shaila. Identifiers: LCCN 2019051804 | ISBN 9780593114292 (hardcover) ISBN 9780593114308 (ebook) Subjects: CYAC: Preparatory schools—Fiction. | Schools—Fiction. Cliques (Sociology)—Fiction. | Murder—Fiction. | Mystery and detective stories. Jews—United States—Fiction. | Long Island (N.Y.)—Fiction. Classification: LCC PZ7.1.G6542 Th 2020 | DDC [Fic]—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019051804 This book is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real places are used fictitiously. Other names, characters, places, and events are products of the author’s imagination, and any resemblance to actual events or places or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.