By Stephen Minch “No Passion in the World Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September/October 2020 Oakland Magic Circle Newsletter Official Website: Facebook:

September/October 2020 Oakland Magic Circle Newsletter Official Website:www.OaklandMagicCircle.com Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/42889493580/ Password: EWeiss This Month’s Contents -. Where Are We?- page 1 - Ran’D Shines at September Lecture- page 2 - October 6 Meeting-Halloween Special -page 4 - September Performances- page 5 - Ran’D Answers Five Questions- page 9 - Phil Ackerly’s New Book & Max Malini at OMC- page 10 - Magical Resource of the Month -Black Magician Matter II-page 12 -The Funnies- page 16 - Magic in the Bay Area- Virtual Shows & Lectures – page 17 - Beyond the Bay Shows, Seminars, Lectures & Events in July- page 25 - Northern California Magic Dealers - page 32 Everything that is highlighted in blue in this newsletter should be a link that takes you to that person, place or event. WHERE ARE WE? JOIN THE OAKLAND MAGIC CIRCLE---OR RENEW OMC has been around since 1925, the oldest continuously running independent magic club west of the Mississippi. Dozens of members have gone on to fame and fortune in the magic world. When we can return to in-person meetings it will be at Bjornson Hall with a stage, curtains, lighting and our excellent new sound system. The expanding library of books, lecture notes and DVDs will reopen. And we will have our monthly meetings, banquets, contests, lectures, teach-ins plus the annual Magic Flea Market & Auction. Good fellowship is something we all miss. Until then we are proud to be presenting a series of top quality virtual lectures. A benefit of doing virtual events is that we can have talent from all over the planet and the audiences are not limited to those who can drive to Oakland. -

Bibliography of Works by Roberto Giobbi Status: May 2019

Bibliography of Works by Roberto Giobbi Status: May 2019 Books • Fantasia in As-Dur, Magic Communication Roberto Giobbi, Basel 1987 • CardPerfect, Magic Communication Roberto Giobbi, Basel 1987 • roberto-light, Magic Communication Roberto Giobbi, Basel 1988 • Grosse Kartenschule Band 1, Magic Communication Roberto Giobbi, Basel 1992 • Grosse Kartenschule Band 2, Magic Communication Roberto Giobbi, Basel 1992 • roberto extra-light, Magic Communication Roberto Giobbi, Basel 1992 • Grosse Kartenschule Band 3, Magic Communication Roberto Giobbi, Basel 1994 • Grosse Kartenschule Band 4, Magic Communication Roberto Giobbi, Basel 1994 • Cours de cartomagie moderne Tome 1, Magix, Strasbourg 1994 • Gran Escuela Cartomagica, Volumenes 1 y 2, Paginas, Madrid 1994 • Card College Volume 1, Hermetic Press, Seattle 1995 • Gran Escuela Cartomagica, Volumenes 3 y 4, Paginas, Madrid 1995 • roberto super-light, Magic Communication Roberto Giobbi, Basel 1995 • Cours de Cartomagie Moderne Tome II, Magix, Strasbourg 1996 • Roberto Light, Paginas, Madrid 1996 • Roberto Super Light, Paginas, Madrid 1996 • Roberto Extra Light, Paginas, Madrid 1996 • Card College 1, Corso di Cartomagia Moderna, Florence Art Edizioni, Firenze 1998 • Card College 2, Corso di Cartomagia Moderna, Florence Art Edizioni, Firenze 1999 • Il sogno del baro, Florence Art Edizioni, Firenze 1999 • Card College 3, Corso di Cartomagia Moderna, Florence Art Edizioni, Firenze 2001 • Roberto Light, Florence Art Edizioni, Firenze 2001 • Roberto Extra-Light, Florence Art Edizioni, Firenze 2001 • Roberto Super-Light, Florence Art Edizioni, Firenze 2001 • Card College Volume 1 (Japanese version), Tokyo 2001 • Card College Volume 2 (Japanese version), Tokyo 2002 • Card College Volume 5, Hermetic Press, Seattle 2003 • Grosse Kartenschule Band 5, Magic Communication Roberto Giobbi, Basel 2003 • Cours de Cartomagie Moderne Tome 3, Magix, Strasbourg 2005 • Card College Light, Hermetic Press, Seattle 2006 • Roberto Light (version française), C.C. -

Biblioteca Digital De Cartomagia, Ilusionismo Y Prestidigitación

Biblioteca-Videoteca digital, cartomagia, ilusionismo, prestidigitación, juego de azar, Antonio Valero Perea. BIBLIOTECA / VIDEOTECA INDICE DE OBRAS POR TEMAS Adivinanzas-puzzles -- Magia anatómica Arte referido a los naipes -- Magia callejera -- Música -- Magia científica -- Pintura -- Matemagia Biografías de magos, tahúres y jugadores -- Magia cómica Cartomagia -- Magia con animales -- Barajas ordenadas -- Magia de lo extraño -- Cartomagia clásica -- Magia general -- Cartomagia matemática -- Magia infantil -- Cartomagia moderna -- Magia con papel -- Efectos -- Magia de escenario -- Mezclas -- Magia con fuego -- Principios matemáticos de cartomagia -- Magia levitación -- Taller cartomagia -- Magia negra -- Varios cartomagia -- Magia en idioma ruso Casino -- Magia restaurante -- Mezclas casino -- Revistas de magia -- Revistas casinos -- Técnicas escénicas Cerillas -- Teoría mágica Charla y dibujo Malabarismo Criptografía Mentalismo Globoflexia -- Cold reading Juego de azar en general -- Hipnosis -- Catálogos juego de azar -- Mind reading -- Economía del juego de azar -- Pseudohipnosis -- Historia del juego y de los naipes Origami -- Legislación sobre juego de azar Patentes relativas al juego y a la magia -- Legislación Casinos Programación -- Leyes del estado sobre juego Prestidigitación -- Informes sobre juego CNJ -- Anillas -- Informes sobre juego de azar -- Billetes -- Policial -- Bolas -- Ludopatía -- Botellas -- Sistemas de juego -- Cigarrillos -- Sociología del juego de azar -- Cubiletes -- Teoria de juegos -- Cuerdas -- Probabilidad -

Roberto Giobbi's

A K R . bertoS Dear Roberto Giobbi can you help me develop a philosophy of magic... ?(...and 51 other vital questions for the performing magician.) Roberto Giobbi’s A K R . bertoS Can you help me develop a philosophy of magic... (...and 51 other vital questions for the performing magician.) Designed by Barbara Giobbi-Ebnöther Photographs by Barbara Giobbi-Ebnöther Completely Revised Edition June 2014 Lybrary.com ASK ROBERTO Contents Foreword 6 1. Injog Overhand Shuffle 10 2. Presentation Ideas 12 3. Three Card Monte 15 4. How to Study 16 5. Staystack 18 6. Fear of Starting to Perform 20 7. Memorized Version of Out of Sight Out of Mind 28 8. Think Of A Card Routines 30 9. Gilbreath Principle 33 10. Magician is Only an Actor Playing the Role of a Magician 36 11. Too Perfect Theory 45 12. How Many Effects? 51 13. Creative Process 54 14. Bottom Deal Applications 61 15. Philosophy of Magic 65 16. Origin of Display Pass 68 17. Trick That Can’t Be Explained 73 18. In Spectator’s Hands 77 19. Effect Categories for Cards 82 20. Vernon’s Travellers 97 21. Why do Magic? 101 22. Ten Best Card Effects 104 23. Practice 115 24. Best Self-Working Card Trick 118 25. Starting with Card Magic 121 26. Tabled Faro/Riffle Shuffle 125 27. Delayed Setup 129 28. Program Construction of an Act 133 29. How To Prepare For A Competition 143 30. Dirty Cards 149 31. Constructivism 155 32. Favorite Card Routine 162 33. Favorite ESP Card Trick 169 4 . -

The Underground Sessions Page 36

MAY 2013 TONY CHANG DAN WHITE DAN HAUSS ERIC JONES BEN TRAIN THE UNDERGROUND SESSIONS PAGE 36 CHRIS MAYHEW MAY 2013 - M-U-M Magazine 3 MAGIC - UNITY - MIGHT Editor Michael Close Editor Emeritus David Goodsell Associate Editor W.S. Duncan Proofreader & Copy Editor Lindsay Smith Art Director Lisa Close Publisher Society of American Magicians, 6838 N. Alpine Dr. Parker, CO 80134 Copyright © 2012 Subscription is through membership in the Society and annual dues of $65, of which $40 is for 12 issues of M-U-M. All inquiries concerning membership, change of address, and missing or replacement issues should be addressed to: Manon Rodriguez, National Administrator P.O. Box 505, Parker, CO 80134 [email protected] Skype: manonadmin Phone: 303-362-0575 Fax: 303-362-0424 Send assembly reports to: [email protected] For advertising information, reservations, and placement contact: Mona S. Morrison, M-U-M Advertising Manager 645 Darien Court, Hoffman Estates, IL 60169 Email: [email protected] Telephone/fax: (847) 519-9201 Editorial contributions and correspondence concerning all content and advertising should be addressed to the editor: Michael Close - Email: [email protected] Phone: 317-456-7234 Submissions for the magazine will only be accepted by email or fax. VISIT THE S.A.M. WEB SITE www.magicsam.com To access “Members Only” pages: Enter your Name and Membership number exactly as it appears on your membership card. 4 M-U-M Magazine - MAY 2013 M-U-M MAY 2013 MAGAZINE Volume 102 • Number 12 26 28 36 PAGE STORY 27 COVER S.A.M. NEWS 6 From -

[email protected]

[email protected] Sherman, Texas ‐ Lawrence Hass is professor of humanities at Austin College. He also has an international reputation as a sleight of hand magician and holds the position of associate dean of Jeff McBride’s Magic & Mystery School in Las Vegas. Dr. Hass came to Austin College in July of 2009 when his wife Dr. Marjorie Hass became the College’s 15th president. Prior to this, he was professor of philosophy and theatre arts at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania, where he was an award‐winning teacher of philosophy and theatre, specializing in phenomenology, aesthetics, magic performance, and the history and philosophy of magic. During his 18‐year tenure at Muhlenberg College, Dr. Hass founded and directed the “Theory and Art of Magic” program—a college‐level co‐curricular program that was dedicated to the study and appreciation of the magical arts. From 1999 to 2009, the “Theory and Art of Magic” program featured performances, talks, and lectures by such world‐leading stars of magic as David Blaine, Eugene Burger, Roberto Giobbi, Max Howard, René Lavand, Max Maven, Jeff McBride, Robert E. Neale, Jim Steinmeyer, Juan Tamariz, and Teller (among many others). By the end of its 11‐year run, the “Theory and Art of Magic” program was drawing attendees—magicians, students, and scholars of magic—from all over the country and internationally. As an outgrowth of the program, Dr. Hass founded Theory and Art of Magic Press in 2007 to publish books, DVDs, and other materials that would connect with people wanting to perform and think about magic in a deeper way. -

Free Issue 68.Pdf

Welcome to your FREE evaluation copy of Magicseen Magicseen is published every 2 months and is available via a 1 or 2 year subscription, either in printed copy format delivered by mail, or as a download. You can also opt to take out an open ended printed copy Pay As You Go subscription, in which you provide payment card details and we charge you for a single issue each time a new one appears. If you sign up for one of our subscription options above here are the EXTRA benefits that you will enjoy. 1 or 2 year printed copy or PAYG subscribers receive 20% off all Magicseen books and E-Books plus they can opt to receive a free download copy of each issue in advance of the printed copy arriving. Download subscribers receive 20% off all Magicseen books and E-Books plus every time a new issue is released, they can select to receive any two further download back issues for FREE For more info and to subscribe go to www.magicseen.co.uk Magicseen, Anne's Park, Cowley, Exeter EX5 5EN, England Tel: +44 (0)1392 490565 Magicseen is sponsored by Card Shark (www.card-shark.de) PHONEBOX > MASTERCLASS > LETTERS > PRODUCT REVIEWS MAGAZINE IssueMAGICseen No. 68 RRP £5.50 Vol 12. No.2 May 2016 Paul Daniels A look AT his brilliant career Xavier Tapias Rubbish & Robots! Vox Magique Plus: It Takes TwO... > CLOWNING > DEALERS’ BOOTH > HOW TO BOOK MORE SHOWS > RAFAEL RULES THE WORLD JOSHUA JUST JAY MAGIC MAGICSEEN > YOU’LL LIKE IT... BUT NOT A LOT! NEVER TOUCH OR SEE THE CARD...YET KNOW EXACTLY WHAT WAS DRAWN! NO CARBON COPIES • NO PEEKING • EXAMINABLE • SELF CONTAINED AVAILABLE AT: EDITOR’S LETTER ummer is hopefully on the way and we have a bright and Ssunny issue to get you in the mood (was that cheesy enough for you?). -

Prices Correct Till May 19Th

Online Name $US category $Sing Greater Magic Volume 18 - Charlie Miller - DVD $ 30.00 Videos$ 48.00 Greater Magic Volume 42 - Dick Ryan - DVD $ 30.00 Videos$ 48.00 Greater Magic Volume 23 - Bobo - DVD $ 30.00 Videos$ 48.00 Greater Magic Volume 20 - Impromptu Magic Vol.1 - DVD $ 30.00 Videos$ 48.00 Torn And Restored Newspaper by Joel Bauer - DVD$ 30.00 Videos$ 48.00 City Of Angels by Peter Eggink - Trick $ 25.00 Tricks$ 40.00 Silk Poke Vanisher by Goshman - Trick $ 4.50 Tricks$ 7.20 Float FX by Trickmaster - Trick $ 30.00 Tricks$ 48.00 Stealth Assassin Wallet (with DVD) by Peter Nardi and Marc Spelmann - Trick$ 180.00 Tricks$ 288.00 Moveo by James T. Cheung - Trick $ 30.00 Tricks$ 48.00 Coin Asrah by Sorcery Manufacturing - Trick $ 30.00 Tricks$ 48.00 All Access by Michael Lair - DVD $ 20.00 Videos$ 32.00 Missing Link by Paul Curry and Mamma Mia Magic - Trick$ 15.00 Tricks$ 24.00 Sensational Silk Magic And Simply Beautiful Silk Magic by Duane Laflin - DVD$ 25.00 Videos$ 40.00 Magician by Sam Schwartz and Mamma Mia Magic - Trick$ 12.00 Tricks$ 19.20 Mind Candy (Quietus Of Creativity Volume 2) by Dean Montalbano - Book$ 55.00 Books$ 88.00 Ketchup Side Down by David Allen - Trick $ 45.00 Tricks$ 72.00 Brain Drain by RSVP Magic - Trick $ 45.00 Tricks$ 72.00 Illustrated History Of Magic by Milbourne and Maurine Christopher - Book$ 25.00 Books$ 40.00 Best Of RSVPMagic by RSVP Magic - DVD $ 45.00 Videos$ 72.00 Paper Balls And Rings by Tony Clark - DVD $ 35.00 Videos$ 56.00 Break The Habit by Rodger Lovins - Trick $ 25.00 Tricks$ 40.00 Can-Tastic by Sam Lane - Trick $ 55.00 Tricks$ 88.00 Calling Card by Rodger Lovins - Trick $ 25.00 Tricks$ 40.00 More Elegant Card Magic by Rafael Benatar - DVD$ 35.00 Videos$ 56.00 Elegant Card Magic by Rafael Benatar - DVD $ 35.00 Videos$ 56.00 Elegant Cups And Balls by Rafael Benatar - DVD$ 35.00 Videos$ 56.00 Legless by Derek Rutt - Trick $ 150.00 Tricks$ 240.00 Spectrum by R. -

Roberto Giobbi's Introduction to Card Magic 3 ♦♣ Thanks!

Roberto Giobbi‘s Introduction to Card Magic © Copyright Notice Copyright © 2012 Roberto Giobbi. All rights reserved. For personal use only. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or utilized by any information storage or retrieval system, nor shall this publication or any part of it be used commercially, or associated with any product or service, or distributed by itself or with other products or services without written permission from the copyright owner. For information about permissions contact: Roberto Giobbi Schlossbergstrasse 5 4132 Muttenz Switzerland Tf:++41-(0)61-463 08 44 e-mail: [email protected] Donation This book is being distributed at no charge to encourage the art of magic. If you enjoyed it and can afford it please make a small contribution. $5 is fine, that’s how much many an app costs, $10 is much appreciated, and if you are a millionaire you may put me in your will. Thank you for letting me know that you appreciated this work and that you would like me to do more. Please click the „Donate“ button below now. THANK YOU! ♦♣ Read Me This PDF is meant as an electronic publication, but you may also print and bind it and use it as a book (obviously without the benefit of film clips) – print-on-demand services such as lulu.com do this at a very reasonable price. Best Use The best way of making use of this PDF is to load it on an iPad or similar device. -

What Are the Best Magic Books for Beginners?

www.lybrary.com/ – the one with two Y’s You may freely distribute and print this article as long as the article including this header, is used in its entirety and is not changed in any way. For questions you can contact the author, Chris Wasshuber, at [email protected] __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ What are the best magic books for beginners? by Chris Wasshuber This is actually a very hard question to answer, because there are all kinds of beginners with all kinds of interests. I will limit myself to the performance of close-up where I gathered my own experience doing magic, and there I will focus on magic with cards, coins, and mentalism. If you want to take a short cut and not read through the rest of my opinion here are the three best classics which are wonderful and affordable: The Royal Road to Card Magic by Jean Hugard and Fred Braue The New Modern Coin Magic by J.B. Bobo Practical Mental Effects by Ted Annemann CARD MAGIC If I would have to suggest one book or one series of books I would pick Roberto Giobbi's Card College, which comes in five volumes. This is a modern classic which will guide you from the first time you hold a pack of cards in your hands to the heights of card magic. It teaches you much more than sleights and tricks. It covers a lot of theory, misdirection, audience management, routining - all the things which make a trick a miracle, or a guy doing magic a performer and entertainer. -

On the Theory of Magic

Roberto Giobbi www.robertogiobbi.com On the Theory of Magic This is the start of a series of essays that I would like to dedicate to the theory of magic, however, it will be practical theory. What at first reading might sound contradictory is really a thought that was already formulated by Aristotle: he maintained that thinking itself doesn’t move anything, but if thinking is targeted at a purpose it becomes practical. Many years as a writer of magic books, as well as a coach in lectures, workshops and private lessons, have strengthened in me the belief that although you certainly move forward in small steps by learning specific techniques and tricks, you onlygrow by knowing, understanding and applying theories, thoughts and concepts. As Ascanio once remarked to me, «You have to be wide and deep.» Information is important, but only understanding makes a practitioner of any discipline - be it gardening, surgery, music or magic - access the next level of competence in the pyramid of (artistic) excellence. Therefore, this series of columns is about the thought and practice that will allow us to do just that, regardless of what level we are currently in, because we are all eternal students. This is (Not) a Theory At a recent magic convention someone said to me, «You know, I hate theory, because I think it isn’t any good in magic – all I believe in is doing it in front of an audience and gaining experience.» I answered, «Do you realize that this is a theory?» I can’t remember what he then said, but I think it was another theory.. -

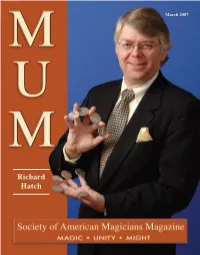

Richard Hatch Richard Hatch

March 2007 Richard Hatch Richard Hatch PHOTO: JEFF GRASS 50 MUM March 2007 “The more a magician reads about magic, the more he realizes how much more there is to learn and how many more magic books there are to read.” Robert Lund (1925-1995), Founder The American Museum of Magic The Accidental Magic Bookman By Bill Palmer Born in California, raised in Germany, and edu- Germany where his father worked for a clandes- cated at Yale University, how did Richard Hatch tine branch of the U.S. Government for two wind up in oxymoronic Humble, Texas? And how years before completing a year of post-doctoral did this same fellow go from having a Master of research at Heidelberg University. Attending Philosophy in Physics to being a respected magic German kindergarten, Richard began to learn the historian, German translator, and successful pub- language at this early age, but it would not pay lisher and book dealer in just a few years? “My off until years later. wife and parents would also like to know what When Hatch was six years old, the family happened,” Richard says with a smile. moved back to the United States and to Ames, Richard Clawson Hatch was born May 24, Iowa, when his father was offered a tenured posi- 1955 in Pasadena, California where his father, tion with the Physics Department of Iowa State Eastman Nibley Hatch, was completing his doc- University. In 1964, Richard received his intro- toral studies in nuclear physics at the renowned duction into magic when he was given a copy California Institute of Technology.