Historians Have Given Various Interpretations of Middle-Class

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lillian Wald (1867 - 1940)

Lillian Wald (1867 - 1940) Nursing is love in action, and there is no finer manifestation of it than the care of the poor and disabled in their own homes Lillian D. Wald was a nurse, social worker, public health official, teacher, author, editor, publisher, women's rights activist, and the founder of American community nursing. Her unselfish devotion to humanity is recognized around the world and her visionary programs have been widely copied everywhere. She was born on March 10, 1867, in Cincinnati, Ohio, the third of four children born to Max and Minnie Schwartz Wald. The family moved to Rochester, New York, and Wald received her education in private schools there. Her grandparents on both sides were Jewish scholars and rabbis; one of them, grandfather Schwartz, lived with the family for several years and had a great influence on young Lillian. She was a bright student, completing high school when she was only 15. Wald decided to travel, and for six years she toured the globe and during this time she worked briefly as a newspaper reporter. In 1889, she met a young nurse who impressed Wald so much that she decided to study nursing at New York City Hospital. She graduated and, at the age of 22, entered Women's Medical College studying to become a doctor. At the same time, she volunteered to provide nursing services to the immigrants and the poor living on New York's Lower East Side. Visiting pregnant women, the elderly, and the disabled in their homes, Wald came to the conclusion that there was a crisis in need of immediate redress. -

Selected Highlights of Women's History

Selected Highlights of Women’s History United States & Connecticut 1773 to 2015 The Permanent Commission on the Status of Women omen have made many contributions, large and Wsmall, to the history of our state and our nation. Although their accomplishments are too often left un- recorded, women deserve to take their rightful place in the annals of achievement in politics, science and inven- Our tion, medicine, the armed forces, the arts, athletics, and h philanthropy. 40t While this is by no means a complete history, this book attempts to remedy the obscurity to which too many Year women have been relegated. It presents highlights of Connecticut women’s achievements since 1773, and in- cludes entries from notable moments in women’s history nationally. With this edition, as the PCSW celebrates the 40th anniversary of its founding in 1973, we invite you to explore the many ways women have shaped, and continue to shape, our state. Edited and designed by Christine Palm, Communications Director This project was originally created under the direction of Barbara Potopowitz with assistance from Christa Allard. It was updated on the following dates by PCSW’s interns: January, 2003 by Melissa Griswold, Salem College February, 2004 by Nicole Graf, University of Connecticut February, 2005 by Sarah Hoyle, Trinity College November, 2005 by Elizabeth Silverio, St. Joseph’s College July, 2006 by Allison Bloom, Vassar College August, 2007 by Michelle Hodge, Smith College January, 2013 by Andrea Sanders, University of Connecticut Information contained in this book was culled from many sources, including (but not limited to): The Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, the U.S. -

Women's History Is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating in Communities

Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook Prepared by The President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History “Just think of the ideas, the inventions, the social movements that have so dramatically altered our society. Now, many of those movements and ideas we can trace to our own founding, our founding documents: the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. And we can then follow those ideas as they move toward Seneca Falls, where 150 years ago, women struggled to articulate what their rights should be. From women’s struggle to gain the right to vote to gaining the access that we needed in the halls of academia, to pursuing the jobs and business opportunities we were qualified for, to competing on the field of sports, we have seen many breathtaking changes. Whether we know the names of the women who have done these acts because they stand in history, or we see them in the television or the newspaper coverage, we know that for everyone whose name we know there are countless women who are engaged every day in the ordinary, but remarkable, acts of citizenship.” —- Hillary Rodham Clinton, March 15, 1999 Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook prepared by the President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History Commission Co-Chairs: Ann Lewis and Beth Newburger Commission Members: Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole, J. Michael Cook, Dr. Barbara Goldsmith, LaDonna Harris, Gloria Johnson, Dr. Elaine Kim, Dr. -

Shapers of Modern America the WW1 AMERICA MURAL

Shapers of Modern America THE WW1 AMERICA MURAL Inspired by the expansive Panthéon de la Guerre mural completed by French artists 100 years ago to memorialize World War I, the Minnesota Historical Society commissioned Minneapolis artist David Geister to paint a 30- foot mural depicting individ- ual Americans who helped shape, or were shaped by, the war and who had a hand in the making of modern America. The mural complements the WW1 America exhibit on view at the Minnesota History Center through November 11, 2017. THEN According to art historian Mark Levitch, the Panthéon de la Guerre was the most ambitious World War I memorial. The effort, led by Auguste FrançoisMarie Gorguet and Pierre Carrier Belleuse, began in September 1914 and was completed in October 1918. Stretching more than 400 feet in length and depicting nearly 6,000 allied troops, the completed work was viewed by millions of French citizens in a specially constructed building in Paris. In 1927 some US businessmen purchased the panorama and transported it to the United States to be displayed— more as spectacle than somber remembrance— on a 13 year tour to Chicago, Cleveland, New York, San Francisco, and Wash ington, DC. The Great Depression and a second world war overshadowed the work of Gorguet and Carrier Belleuse. The artwork was crated and abandoned on a Baltimore loading dock for more than a dozen years. It was not until 1956 that Daniel MacMorris, a Kansas City artist and World War I veteran, secured the deteriorating Panel 1, The War. (DOUG OHMAN) Panthéon for the Liberty Memorial in Kansas 260 MINNESOTA HISTORY FALL 2017 261 City, Missouri. -

About Henry Street Settlement

TO BENEFIT Henry Street Settlement ORGANIZED BY Art Dealers Association of America March 1– 5, Gala Preview February 28 FOUNDED 1962 Park Avenue Armory at 67th Street, New York City MEDIA MATERIALS Lead sponsoring partner of The Art Show The ADAA Announces Program Highlights at the 2017 Edition of The Art Show ART DEALERS ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA 205 Lexington Avenue, Suite #901 New York, NY 10016 [email protected] www.artdealers.org tel: 212.488.5550 fax: 646.688.6809 Images (left to right): Scott Olson, Untitled (2016), courtesy James Cohan; Larry Bell with Untitled (Wedge) at GE Headquarters, Fairfield, CT in 1984, courtesy Anthony Meier Fine Arts; George Inness, A June Day (1881), courtesy Thomas Colville Fine Art. #TheArtShowNYC Program Features Keynote Event with Museum and Cultural Leaders from across the U.S., a Silent Bidding Sale of an Alexander Calder Sculpture to Benefit the ADAA Foundation, and the Annual Art Show Gala Preview to Benefit Henry Street Settlement ADAA Member Galleries Will Present Ambitious Solo Exhibitions, Group Shows, and New Works at The Art Show, March 1–5, 2017 To download hi-res images of highlights of The Art Show, visit http://bit.ly/2kSTTPW New York, January 25, 2017—The Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA) today announced additional program highlights of the 2017 edition of The Art Show. The nation’s most respected and longest-running art fair will take place on March 1-5, 2017, at the Park Avenue Armory in New York, with a Gala Preview on February 28 to benefit Henry Street Settlement. -

NINR History Book

NINR NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF NURSING RESEARCH PHILIP L. CANTELON, PhD NINR: Bringing Science To Life National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) with Philip L. Cantelon National Institute of Nursing Research National Institutes of Health Publication date: September 2010 NIH Publication No. 10-7502 Library of Congress Control Number 2010929886 ISBN 978-0-9728874-8-9 Printed and bound in the United States of America TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface The National Institute of Nursing Research at NIH: Celebrating Twenty-five Years of Nursing Science .........................................v Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................ix Chapter One Origins of the National Institute of Nursing Research .................................1 Chapter Two Launching Nursing Science at NIH ..............................................................39 Chapter Three From Center to Institute: Nursing Research Comes of Age .....................65 Chapter Four From Nursing Research to Nursing Science ............................................. 113 Chapter Five Speaking the Language of Science ............................................................... 163 Epilogue The Transformation of Nursing Science ..................................................... 209 Appendices A. Oral History Interviews .......................................................................... 237 B. Photo Credits ........................................................................................... 239 -

![Biographies of Women Scientists for Young Readers. PUB DATE [94] NOTE 33P](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6994/biographies-of-women-scientists-for-young-readers-pub-date-94-note-33p-1256994.webp)

Biographies of Women Scientists for Young Readers. PUB DATE [94] NOTE 33P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 368 548 SE 054 054 AUTHOR Bettis, Catherine; Smith, Walter S. TITLE Biographies of Women Scientists for Young Readers. PUB DATE [94] NOTE 33p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Biographies; Elementary Secondary Education; Engineering Education; *Females; Role Models; Science Careers; Science Education; *Scientists ABSTRACT The participation of women in the physical sciences and engineering woefully lags behind that of men. One significant vehicle by which students learn to identify with various adult roles is through the literature they read. This annotated bibliography lists and describes biographies on women scientists primarily focusing on publications after 1980. The sections include: (1) anthropology, (2) astronomy,(3) aviation/aerospace engineering, (4) biology, (5) chemistry/physics, (6) computer science,(7) ecology, (8) ethology, (9) geology, and (10) medicine. (PR) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** 00 BIOGRAPHIES OF WOMEN SCIENTISTS FOR YOUNG READERS 00 "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY Once of Educational Research and Improvement Catherine Bettis 14 EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION Walter S. Smith CENTER (ERIC) Olathe, Kansas, USD 233 M The; document has been reproduced aS received from the person or organization originating it 0 Minor changes have been made to improve Walter S. Smith reproduction quality University of Kansas TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES Points of view or opinions stated in this docu. INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." ment do not necessarily rpresent official OE RI position or policy Since Title IX was legislated in 1972, enormous strides have been made in the participation of women in several science-related careers. -

Xomen's Rights, Historic Sites

Women’s Rights, Historic Sites: A Manhattan Map of Milestones African Burial Ground National Monument (corner of Elk and Duane Streets) was Perkins rededicate her life to improving working conditions for all people. Perkins 71 The first home game of the New York Liberty of the Women’s National Basketball 99 Barbara Walters joined ABC News in 1976 as the first woman to co-host the Researched and written by Pam Elam, Deputy Chief of Staff dedicated. It is estimated that 40% of the adults buried there were women. became the first woman cabinet member when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt Association (WNBA) was played at Madison Square Garden (7th Avenue between network news. ABC News is now located at 7 West 66th Street. Prior to joining Layout design by Ken Nemchin appointed her as Secretary of Labor in 1933. Perkins said: “The door might not be West 31st – 33rd Streets) on June 29, 1997. The Liberty defeated Phoenix 65-57 ABC, she appeared on NBC’s Today Show for 15 years. NBC only officially des- 23 Constance Baker Motley became the first woman Borough President of Manhattan opened to a woman again for a long, long time and I had a kind of duty to other before a crowd of 17,780 women’s basketball fans. ignated her as the program’s first woman co-host in 1974. In 1964, Marlene in 1965; her office was in the Municipal Building at 1 Centre Street. She was also the 1 Emily Warren Roebling, who led the completion of the work on the Brooklyn Bridge women to walk in and sit down on the chair that was offered, and so establish the Sanders -

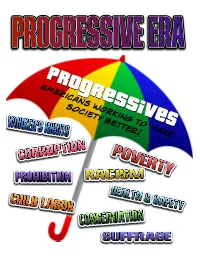

Americans Working to Make Society Better!

Americans working to make society better! New York City The rise of immigration brought millions Slums of people into overcrowded cities like New York City and Chicago. Many families could not afford to buy houses and usually lived in rented apartments or Crowded Tenements. These buildings were run down and overcrowded. These families had few places to turn to for help. Often times, tenements were poorly designed, unsafe, and lacked running water, electricity, and sanitation. Entire neighborhoods of tenement buildings became urban slums. Hull House, Chicago Jacob A Riis was a photographer whose photos of slums and tenements in New York City shocked society. His photography exposed the poor conditions of the lower class to the wealthier citizens and inspired many people to join in Jane Addams efforts to reform laws and improve living conditions in the slums. Jacob A. Riis Jane Addams helped people in a neighborhood of immigrants in Chicago, Illinois. She and her friend, Ellen Starr, bought a house and turned it into a Settlement House to provide services for poor people in the community. Addams' settlement house was called Hull House and it, along with other settlement houses established in other urban areas, offered opportunities such as english classes, child care, and work training to community residents. Large businesses were growing even larger. The rich and powerful wanted to continue their individual success and maintain their power. The federal and local governments became increasingly corrupt. Elected officials would often bribe people for support. Political Machines were organizations that influenced votes and controlled local governments. Politicians would break rules to win elections. -

The Voter February 2019

League of Women Voters of the Jackson Area THE VOTER P.O. Box 68214, Jackson, MS 39286-8214 http://www.lwv-ms.org/Jackson_League.html https://www.facebook.com/LWVJA/ FEBRUARY 2019 League of Women Voters is where hands-on work to safeguard democracy leads to civic improvement PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Carol Andersen February is the anniversary month of the founding of the League of Women Voters. Suffragist Carrie Chapman Catt established the League on February 14, 1920. Six months later, Catt and her fellow suffragists finally won their battle for the ballot box when Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, achieving the three-quarters majority necessary to pass an amendment. February is also Black History Month, and in honor of this annual tribute to African Americans who struggled to achieve full citizenship in American society, I want us to give LWV-JA Meeting Saturday, March 2, 2019 honor to important African American figures in the U.S. Women's Suffrage Movement. Tme: 10:30 – 11:30 AM Edith Mayo, a nationally renowned historian and curator emerita in political and women’s history at Willie Morris Library the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of 4912 Old Canton Road, Jackson, MS American History, has assembled a list of notable African American suffragists who also fought to achieve women’s voting rights. Their work was not Guest Speaker: Jill Mastrototaro always appreciated and in fact, according to Mayo, of Audubon MS black women were often outright excluded from white suffrage organizations and subjected to racist Topic: One Lake Project tactics from white suffragists. -

Sanders, Geterly Women Inamerican History:,A Series. Pook Four, Woien

DOCONIMM RIBOSE ED 186 Ilk 3 SO012596 AUTHOR Sanders, geTerly TITLE Women inAmerican History:,A Series. pook Four,Woien in the Progressive Era 1890-1920.. INSTITUTION American Federation of Teachers, *Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Office,of Education (DHEW), Wastington, D.C. Wolen's Educational Egutty Act Program. PUB DATE 79 NOTE 95p.: For related documents, see SO 012 593-595. AVAILABLE FROM Education Development Center, 55 Chapel Street, Newton, MA 02160 (S2.00 plus $1.30 shipping charge) EDRS gRICE MF01 Plus Postige. PC Not.Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Artists; Authors: *CiVil Rights: *Females; Feminksm; Industrialization: Learning Activities: Organizations (Groups): Secondary Education: Sex Discrioination; *Sex Role: *Social Action: Social Studies;Unions; *United States History: Voting Rights: *Womens Studies ABSTRACT 'The documente one in a series of four on.women in American history, discusses the rcle cf women in the Progressive Era (11390-1920)4 Designed to supplement high school U.S.*history. textbooks; the book is co/mprised of five chapter's. Chapter I. 'describes vtormers and radicals including Jane A3damsand Lillian Wald whs b4tan the settlement house movement:Florence Kelley, who fought for labor legislation:-and Emma Goldmanand Kate RAchards speaking against World War ft Of"Hare who,became pOlitical priscners for I. Chapter III focuses on women in factory workand the labor movement. Excerpts from- diaries reflectthe'work*ng contlitions in factor4es which led to women's ipvolvement in the,AFL andthe tormatton of the National.Wcmenls Trade Union League. Mother Jones, the-Industrial Workers of the World, and the "Bread and Roses"strike (1S12) of 25,000 textile workers in Massachusetts arealso described. -

IN ACTION Newsletter

EDUCATION IN ACTION Volume 1 | Fall 2008 “You have provided a solid basis for continuing conversations about th e brave Jewish wom en in US history. Ruth Bader Ginsburg Justice of the United States ”Supreme Court WE CAME. WE LEARNED. TOGETHER, WE CHANGED. They arrived as educators. Five days later, they departed as advocates. The 24 participants in the Jewish Women’s Archive summer Institute for Educators emerged eager to impart to their colleagues, students, and communities the stories they had heard and the methods they had learned during their four days in Brookline. “I now have a responsibility to share this information with people in my professional world and other worlds.” Debbie Kardon Schwartz, Director of Family Institute participants Emily Shapiro Katz of San Francisco (left) and Yeshi Education at Congregation B’nai Torah Sudbury, MA Gusfield of Oakland, CA, and Alan Rosenberg of Providence, RI (right) listen to a session on teaching with primary sources. “As a Jewish educator and as a Jewish woman,” Debbie Kardon both professional and personal insights and explored Schwartz, Director of Family Education at Congregation B’nai innovative ways to use the Archive’s resources in their Torah in Sudbury, MA, said, “I acquired a greater awareness teaching. “We learned techniques to tell stories that have of JWA resources and all the great women presented there. to be told,” explained Alan Rosenberg of Temple Beth-E in We’ve all become ambassadors for their stories. We now have Providence, RI. the responsibility to bring their voices back into the world. They had traveled from as far away as California, Nebraska, Even more important, I now have a responsibility to share this Kentucky, and Wisconsin.