Media, Memory and Harvey Milk Aspires to Be a Contribution Toward a More Comprehensive History of the Memory of Milk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

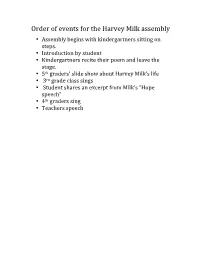

Order of Events for the Harvey Milk Assembly • Assembly Begins with Kindergartners Sitting on Steps

Order of events for the Harvey Milk assembly • Assembly begins with kindergartners sitting on steps. • Introduction by student • Kindergartners recite their poem and leave the stage. • 5th graders’ slide show about Harvey Milk’s life • 3rd grade class sings • Student shares an excerpt from Milk’s “Hope speech” • 4th graders sing • Teachers speech Student 1 Introduction Welcome students of (School Name). Today we will tell you about Harvey Milk, the first gay City Hall supervisor. He has changed many people’s lives that are gay or lesbian. People respect him because he stood up for gay and lesbian people. He is remembered for changing our country, and he is a hero to gay and lesbian people. Fifth Grade Class Slide Show When Harvey Milk was a little boy he loved to be the center of attention. Growing up, Harvey was a pretty normal boy, doing things that all boys do. Harvey was very popular in school and had many friends. However, he hid from everyone a very troubling secret. Harvey Milk was homosexual. Being gay wasn’t very easy back in those days. For an example, Harvey Milk and Joe Campbell had to keep a secret of their gay relationship for six years. Sadly, they broke up because of stress. But Harvey Milk was still looking for a spouse. Eventually, Harvey Milk met Scott Smith and fell in love. Harvey and Scott moved together to the Castro neighborhood of San Francisco, which was a haven for people who were gay, a place where they were respected more easily. Harvey and Scott opened a store called Castro Camera and lived on the top floor. -

LGBTQ America: a Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. THEMES The chapters in this section take themes as their starting points. They explore different aspects of LGBTQ history and heritage, tying them to specific places across the country. They include examinations of LGBTQ community, civil rights, the law, health, art and artists, commerce, the military, sports and leisure, and sex, love, and relationships. MAKING COMMUNITY: THE PLACES AND15 SPACES OF LGBTQ COLLECTIVE IDENTITY FORMATION Christina B. Hanhardt Introduction In the summer of 2012, posters reading "MORE GRINDR=FEWER GAY BARS” appeared taped to signposts in numerous gay neighborhoods in North America—from Greenwich Village in New York City to Davie Village in Vancouver, Canada.1 The signs expressed a brewing fear: that the popularity of online lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) social media—like Grindr, which connects gay men based on proximate location—would soon replace the bricks-and-mortar institutions that had long facilitated LGBTQ community building. -

Las Vegas Pride Names Cleve Jones Parade Grand Marshal

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Ernie Yuen Email: [email protected] Website: www.LasVegasPRIDE.org LAS VEGAS PRIDE NAMES CLEVE JONES PARADE GRAND MARSHAL August 12, 2012, Las Vegas, Nevada: Las Vegas PRIDE is proud to announce the 2012 Annual PRIDE Night Parade on September 7, 2012 will be marshaled by Cleve Jones a human rights activist and founder of the NAMES Project AIDS Quilt. "It is a great privilege and a honor to have Cleve Jones as our 2012 parade grand marshal, He is a great representative for our community and we are happy he is here to celebrate Las Vegas Pride with us." says Las Vegas PRIDE President, Ernie Yuen. Cleve’s career as an activist began in San Francisco during the turbulent 1970s when pioneer gay rights leader, Harvey Milk, befriended him. Following Milk’s election to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, Cleve worked as a student intern in Milk’s office while studying political science at San Francisco State University. Milk and San Francisco Mayor Geroge Moscone were assassinated on November 27, 1978. Following the horrible event, Cleve dropped out of school to work as a legislative consultant at the California Assembly. In 1982, Cleve returned to San Francisco to work in the district office of State Assemblyman Art Agnos. One of the first to recognize the threat of AIDS, Cleve co-founded the San Francisco AIDS Foundation in 1983. Cleve Jones conceived the idea of the AIDS Memorial Quilt at a candlelight memorial for Harvey Milk in 1985. Since then, the Quilt has grown to become the world’s largest community arts project, memorializing the lives of over 80,000 people killed by AIDS. -

Uses of the Judeo-Christian Bible in the Anti-Abolitionist

THIS FIERCE GEOMETRY: USES OF THE JUDEO-CHRISTIAN BIBLE IN THE ANTI-ABOLITIONIST AND ANTI-GAY RHETORIC OF THE UNITED STATES by Michael J. Mazza B. A., State University of New York at Buffalo, 1990 M. A., University of Pittsburgh, 1996 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2009 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Michael J. Mazza It was defended on April 15, 2009 and approved by Nancy Glazener, University of Pittsburgh Moni McIntyre, Duquesne University William Scott, University of Pittsburgh Committee Chair: Jean Ferguson Carr, University of Pittsburgh ii THIS FIERCE GEOMETRY: USES OF THE JUDEO-CHRISTIAN BIBLE IN THE ANTI-ABOLITIONIST AND ANTI-GAY RHETORIC OF THE UNITED STATES Michael J. Mazza, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Copyright © by Michael J. Mazza 2009 iii Jean Ferguson Carr_______ THIS FIERCE GEOMETRY: USES OF THE JUDEO-CHRISTIAN BIBLE IN THE ANTI-ABOLITIONIST AND ANTI-GAY RHETORIC OF THE UNITED STATES Michael J. Mazza, Ph.D. University of Pittsburgh, 2009 This dissertation examines the citational use of the Judeo-Christian Bible in two sociopolitical debates within the United States: first, the debate over the abolition of slavery in the nineteenth century, and second, the contemporary debate over gay rights. This study incorporates two core theses. First, I argue that the contemporary religious right, in its anti-gay use of the Bible, is replicating the hermeneutical practices used by opponents of the abolitionist movement. My second thesis parallels the first: I argue that the contemporary activists who reclaim the Bible as a pro-gay instrument are standing in the same hermeneutical tradition as nineteenth-century Christian abolitionists. -

“Destroy Every Closet Door” -Harvey Milk

“Destroy Every Closet Door” -Harvey Milk Riya Kalra Junior Division Individual Exhibit Student-composed words: 499 Process paper: 500 Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources: Black, Jason E., and Charles E. Morris, compilers. An Archive of Hope: Harvey Milk's Speeches and Writings. University of California Press, 2013. This book is a compilation of Harvey Milk's speeches and interviews throughout his time in California. These interviews describe his views on the community and provide an idea as to what type of person he was. This book helped me because it gave me direct quotes from him and allowed me to clearly understand exactly what his perspective was on major issues. Board of Supervisors in January 8, 1978. City and County of San Francisco, sfbos.org/inauguration. Accessed 2 Jan. 2019. This image is of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors from the time Harvey Milk was a supervisor. This image shows the people who were on the board with him. This helped my project because it gave a visual of many of the key people in the story of Harvey Milk. Braley, Colin E. Sharice Davids at a Victory Party. NBC, 6 Nov. 2018, www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/sharice-davids-lesbian-native-american-makes- political-history-kansas-n933211. Accessed 2 May 2019. This is an image of Sharcie Davids at a victory party after she was elected to congress in Kansas. This image helped me because ti provided a face to go with he quote that I used on my impact section of board. California State, Legislature, Senate. Proposition 6. -

Reach More of the Gay Market

Reach More of the Gay Market Mark Elderkin [email protected] (954) 485-9910 Evolution of the Gay Online Ad Market Concentration A couple of sites with reach Fragmentation Many sites with limited reach Gay Ad Network Aggregation 3,702,065 Monthly Gay Ad Network creates reach Unique Users (30-day Reach by Adify - 04/08) 1995 2000 2005 2010 2 About Gay Ad Network Gay Ad Network . The Largest Gay Audience Worldwide comScore Media Metrix shows that Gay Ad Network has amassed the largest gay reach in the USA and Health & Fitness abroad. (July 2008) Travel & Local . Extensive Network of over 200 LGBT Sites Entertainment Our publisher’s content is relevant and unique. We News & Politics do not allow chat rooms or adult content on our network. All publishers adhere to our strict editorial Women guidelines. Pop Culture . 100% Transparency for Impressions Delivered Parenting Performance reports show advertisers exactly where and when ads are delivered. Ad impressions are Business & Finance organic and never forced. Style . Refined Targeting or Run of Network Young Adult For media efficiency, campaigns can be site targeted, frequency-capped, and geo-targeted. For mass reach, we offer a run of network option. 3 Gay Ad Network: The #1 Gay Media Network Unique US Audience Reach comScore Media Metrix July 2008 . Ranked #1 by 750,000 comScore Media Metrix in Gay and Lesbian Category 500,000 . The fastest growing gay media property. 250,000 . The greatest 0 diversity and Gay Ad PlanetOut LOGOonline depth of content Network Network Network and audience The comScore July 2008 traffic report does not include site traffic segments. -

Harvey Milk Page 1 of 3 Opera Assn

San Francisco Orpheum 1996-1997 Harvey Milk Page 1 of 3 Opera Assn. Theatre Production made possible by a generous grant from Madeleine Haas Russell. Harvey Milk (in English) Opera in three acts by Stewart Wallace Libretto by Michael Korie Commissioned by S. F. Opera, Houston Grand Opera, and New York City Opera The commission for "Harvey Milk" has been funded in substantial part by a generous gift from Drs. Dennis and Susan Carlyle and has been supported by major grants from the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Opera for a New America, a project of OPERA America; the Caddell & Conwell Foundation for the Arts; as well as the National Endowment for the Arts. Conductor CAST Donald Runnicles Harvey Milk Robert Orth Production Messenger James Maddalena Christopher Alden Mama Elizabeth Bishop Set designer Young Harvey Adam Jacobs Paul Steinberg Dan White Raymond Very Costume Designer Man at the opera James Maddalena Gabriel Berry Gidon Saks Lighting Designer Bradley Williams Heather Carson Randall Wong Sound Designer William Pickersgill Roger Gans Richard Walker Chorus Director Man in a tranch coat/Cop Raymond Very Ian Robertson Central Park cop David Okerlund Choreographer Joe Randall Wong Ross Perry Jack Michael Chioldi Realized by Craig Bradley Williams Victoria Morgan Beard Juliana Gondek Musical Preparation Mintz James Maddalena Peter Grunberg Horst Brauer Gidon Saks Bryndon Hassman Adelle Eslinger Scott Smith Bradley Williams Kathleen Kelly Concentration camp inmate Randall Wong Ernest Fredric Knell James Maddalena Synthesizer Programmer -

Queer Periodicals Collection Timeline

Queer Periodicals Collection Timeline 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 Series I 10 Percent 13th Moon Aché Act Up San Francisco Newsltr. Action Magazine Adversary After Dark Magazine Alive! Magazine Alyson Gay Men’s Book Catalog American Gay Atheist Newsletter American Gay Life Amethyst Among Friends Amsterdam Gayzette Another Voice Antinous Review Apollo A.R. Info Argus Art & Understanding Au Contraire Magazine Axios Azalea B-Max Bablionia Backspace Bad Attitude Bar Hopper’s Review Bay Area Lawyers… Bear Fax B & G Black and White Men Together Black Leather...In Color Black Out Blau Blueboy Magazine Body Positive Bohemian Bugle Books To Watch Out For… Bon Vivant 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 Bottom Line Brat Attack Bravo Bridges The Bugle Bugle Magazine Bulk Male California Knight Life Capitol Hill Catalyst The Challenge Charis Chiron Rising Chrysalis Newsletter CLAGS Newsletter Color Life! Columns Northwest Coming Together CRIR Mandate CTC Quarterly Data Boy Dateline David Magazine De Janet Del Otro Lado Deneuve A Different Beat Different Light Review Directions for Gay Men Draghead Drummer Magazine Dungeon Master Ecce Queer Echo Eidophnsikon El Cuerpo Positivo Entre Nous Epicene ERA Magazine Ero Spirit Esto Etcetera 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 -

Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and McCarthy Center Student Scholarship the Common Good 2020 Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference David Donahue Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/mccarthy_stu Part of the History Commons CHANGEMAKERS AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE Biographies inspired by San Francisco’s Ella Hill Hutch Community Center murals researched, written, and edited by the University of San Francisco’s Martín-Baró Scholars and Esther Madríz Diversity Scholars CHANGEMAKERS: AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE © 2020 First edition, second printing University of San Francisco 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117 Published with the generous support of the Walter and Elise Haas Fund, Engage San Francisco, The Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, The University of San Francisco College of Arts and Sciences, University of San Francisco Student Housing and Residential Education The front cover features a 1992 portrait of Ella Hill Hutch, painted by Eugene E. White The Inspiration Murals were painted in 1999 by Josef Norris, curated by Leonard ‘Lefty’ Gordon and Wendy Nelder, and supported by the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Mayor’s Offi ce Neighborhood Beautifi cation Project Grateful acknowledgment is made to the many contributors who made this book possible. Please see the back pages for more acknowledgments. The opinions expressed herein represent the voices of students at the University of San Francisco and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the University or our sponsors. -

Maureen Erwin

Men’s Health, October 2009 Here's what the President told us: "I actually think (taxing soda) is an idea that we should be exploring. There's no doubt that our kids drink way too much soda. And every study that's been done about obesity shows that there is as high a correlation between increased soda consumption and obesity as just about anything else. Obviously it's not the only factor, but it is a major factor…” San Francisco League of Conservation Voters Rafael Mandelman, City College of San Francisco Trustee The Trust for Public Land Steve Ngo, City College of San Francisco Trustee YES on E! Athens Avalon Green Space Former Mayor Art Agnos American Heart Association Biosafety Alliance Former Assemblymember Fiona Ma Public Health Institute Climate Action Now! California Center for Public Health Advocacy Friends of Alta Plaza Park Labor California Medical Association Hidden Garden Steps SEIU 1021 California Dental Association Joe DiMaggio Playground American Federation of Teachers Local 2121 California Dental Hygienists Association Residents for Noe Valley Town Square California Nurses Association Latino Coalition for a Healthy California SEIU Local 87 Hospital Council of Northern California Food Access Community United Educators of San Francisco San Francisco Medical Society Project Open Hand United Food and Commercial Workers Local 648 San Francisco Dental Society San Francisco-Marin Food Bank SEIU-UHW United Healthcare Workers West SF Dental Hygiene Society San Francisco Urban Agriculture Alliance Center for Youth Wellness Tenderloin Healthy Corner Store Coalition Chinese Community Cardiac Council (4C) Tenderloin Hunger Task Force Organizations Mission Neighborhood Health Center (MNHC) San Francisco Democratic Party NICOS Chinese Health Coalition Press Alice B. -

UPPER MARKET AREAS November 27Th

ANNUAL EVENTS International AIDS Candlelight Memorial About Castro / Upper Market 3rd Sunday in May Harvey Milk Day May 22nd Frameline Film Festival / S.F. LGBT International Film Festival June, www.frameline.org S.F. LGBT Pride/Pink Saturday Last weekend in June www.sfpride.org / www.thesisters.org Leather Week/Folsom Street Fair End of September www.folsomstreetevents.org Castro Street Fair 1st Sunday in October HISTORIC+LGBT SIGHTS www.castrostreetfair.org IN THE CASTRO/ Harvey Milk & George Moscone Memorial March & Candlelight Vigil UPPER MARKET AREAS November 27th Film Festivals throughout the year at the iconic Castro Theatre www.castrotheatre.com Castro/Upper Market CBD 584 Castro St. #336 San Francisco, CA 94114 P 415.500.1181 F 415.522.0395 [email protected] castrocbd.org @visitthecastro facebook.com/castrocbd Eureka Valley/Harvey Milk Memorial Branch Library and Mission Dolores (AKA Mission San Francisco de Asis, The Best of Castro / Upper Market José Sarria Court (1 José Sarria Court at 16th and 320 Dolores St. @ 16th St.) Built between 1785 and Market Streets) Renamed in honor of Milk in 1981, the library 1791, this church with 4-foot thick adobe walls is the oldest houses a special collection of GLBT books and materials, and building in San Francisco. The construction work was done by Harvey Milk Plaza/Giant Rainbow Flag (Castro & Harvey Milk’s Former Camera Shop (575 Castro St.) Gay often has gay-themed history and photo displays in its lobby. Native Americans who made the adobe bricks and roof tiles Market Sts) This two-level plaza has on the lower level, a activist Harvey Milk (1930-1978) had his store here and The plaza in front of the library is named José Sarria Court in by hand and painted the ceiling and arches with Indian small display of photos and a plaque noting Harvey Milk’s lived over it. -

October 2014

Brent ACTCM Bushnell & Get a Job at San Quentin INSIDE Sofa Carmi p. 23 p. 7 p. 3 p. 15 p. 17 p. 20 p. 25 OCTOBER 2014 Serving the Potrero Hill, Dogpatch, Mission Bay and SOMA Neighborhoods Since 1970 FREE Jackson Playground to Receive $1.6 Million, Mostly to Plan Clubhouse Upgrades BY KEITH BURBANK The Eastern Neighborhood Citi- zen’s Advisory Committee (ENCAC) has proposed that San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department invest $1.6 million in developer fees over the next four years to improve Jackson Playground. One million dollars would be directed towards developing designs to renovate the playground’s clubhouse, which Rec and Park estimates will cost $13.5 million to fully execute, with a higher price tag if the building is expanded. The Scents of Potrero Hill ENCAC’s recommendations will be transmitted to the San Francisco BY RYAN BERGMANN Above, First Spice Company blends many spices Board of Supervisors, where they’re in its Potrero location, which add to the fragrance expected to be adopted. According Potrero Hill has a cacophony of in the air, including, red pepper, turmeric, bay to the Committee’s bylaws, ENCAC smells, emanating from backyard leaves, curry powder, coriander, paprika, sumac, collaborates “with the Planning De- gardens, street trees, passing cars, monterey chili, all spice, and rosemary. Below, partment and the Interagency Plan and neighborhood restaurants and Anchor Steam at 17th and Mariposa, emits Implementation Committee on pri- the aroma of barley malt cooking in hot water. bakeries. But two prominent scents oritizing…community improvement PHOTOGRAPHS BY GABRIELLE LURIE tend to linger year-round, no mat- projects and identifying implemen- ter which way the wind is blowing, tation details as part of an annual evolving throughout the day.