Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT TAYLOR, JAMI KATHLEEN. the Adoption of Gender Identity Inclusive Legislation in the American States. (Under the Direct

ABSTRACT TAYLOR, JAMI KATHLEEN. The Adoption of Gender Identity Inclusive Legislation in the American States. (Under the direction of Andrew J. Taylor.) This research addresses an issue little studied in the public administration and political science literature, public policy affecting the transgender community. Policy domains addressed in the first chapter include vital records laws, health care, marriage, education, hate crimes and employment discrimination. As of 2007, twelve states statutorily protect transgender people from employment discrimination while ten include transgender persons under hate crimes laws. An exploratory cross sectional approach using logistic regression found that public attitudes largely predict which states adopt hate crimes and/or employment discrimination laws. Also relevant are state court decisions and the percentage of Democrats within the legislature. Based on the logistic regression’s classification results, four states were selected for case study analysis: North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Massachusetts. The case studies found that legislators are often reluctant to support transgender issues due to the community’s small size and lack of resources. Additionally, transgender identity’s association with gay rights is both a blessing and curse. In conservative districts, particularly those with large Evangelical communities, there is strong resistance to LGBT rights. However, in more tolerant areas, the association with gay rights advocacy groups can foster transgender inclusion in statutes. Legislators perceive more leeway to support LGBT rights. However, gay activists sometimes remove transgender inclusion for political expediency. As such, the policy core of many LGBT interest groups appears to be gay rights while transgender concerns are secondary items. In the policy domains studied, transgender rights are an extension of gay rights. -

A Rhetorical Analysis of Same-Sex Marriage David Alexander Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2007 Redefining What It Means to Be a Republican: A Rhetorical Analysis of Same-Sex Marriage David Alexander Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Alexander, David, "Redefining What It Means to Be a Republican: A Rhetorical Analysis of Same-Sex Marriage" (2007). All Theses. 189. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/189 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REDEFINING WHAT IT MEANS TO BE A REPUBLICAN: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF SAME-SEX MARRIAGE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Professional Communication by David Brooks Alexander August 2007 Accepted by: Dr. Teresa Fishman, Committee Chair Dr. Susan Hilligoss Dr. Joseph Sample i ABSTRACT This thesis examines the same-sex marriage debate within the Republican Party and how the Family Research Council and the Log Cabin Republicans construct their rhetorical arguments using Aristotelian appeals. By defining the debate according to Lloyd Bitzer’s rhetorical situation, this thesis considers the rhetorical sustainability of these organizations’ claims about same-sex marriage and the implications for the future of the Republican Party. The United States is witnessing the increasing presence of gays and lesbians in the media and everyday life. The history of homosexuals living their lives behind closed doors is becoming a thing of the past. -

Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California The Freedom to Marry Oral History Project Bill Smith Bill Smith on Political Operations in the Fight to Win the Freedom to Marry Interviews conducted by Martin Meeker in 2015 Copyright © 2017 by The Regents of the University of California ii Since 1954 the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library, formerly the Regional Oral History Office, has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Bill Smith dated September 14, 2016. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

With Larry Sinclair (Gay O Homosexuality More Tryst with Obama)

Obama re-election and Larry Sinclair gay blackmail issue, Young, Bland and Spencer deaths#taitz0 NewsFollowup.com Obama Sitemap Obama Search Pictorial index home .... OBAMA TOP 10 FRAUD .... Power, Celebrity & Homosexuality more Richard Nixon was gay? Obama Gay / VP Joe Biden and Larry Sinclair Larry Sinclair - Obama book: Cocaine, Sex, Hank Blackmail Williams Jr. Lies & Murder Homophobe? Power, Celebrity & HillBuzz interview with Larry Sinclair (gay o Homosexuality more tryst with Obama) News for the 99% ...................................Refresh F5...archive home 50th Anniversary of JFK assassination "Event of a Lifetime" at the Fess Parker Double Tree Inn. JFKSantaBarbara. NFU MOST ACTIVE PA Go to Alphabetic list Academic Freedom Conference Bill Frist's gay 'hanky code' ... Southern Obama Death List Examiner Who is Barack Hussein Obama/Barry Rothschild Timeline Hospitality. Soetoro? It is alleged that Barack Obama has spent Deval Patrick officiated Barney Franks Bush / Clinton Body Count $950,000 to $1.7 million with 11 law firms in 12 marriage to Jim Ready ... more states to block disclosure of his personal records; Three rulings in Sinclairs favor below which includes birth information, K-12 education, =go to NFU pages Occidental College, Columbia University, and Patton Boggs Three Harvard Law School. Back to Obama Home Obama Linked to Gay Murders According to Norma http://www.newsfollowup.com/obama_gay_blackmail_blagojevich_fitzgerald.htm#taitz0[5/28/2014 6:21:52 PM] Obama re-election and Larry Sinclair gay blackmail issue, Young, Bland and Spencer deaths#taitz0 rulings in Sinclairs favor Jean, whose son, Donald, who was a Choir Director Far Right Obama Truthers Kal Penn, gay actor, ex- White House Office in Reverend Wright's infamous Trinity United of Public Engagement, associate director in Church of Christ, she has been warned that her own Spencer, Bland and Young Obama admin more life is in danger by the Chicago Police Department. -

The Puzzling Persistence of "Don't Ask, Don't Tell"

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences 5-13-2009 The Puzzling Persistence of "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" Elizabeth D. King University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Part of the American Politics Commons Recommended Citation King, Elizabeth D., "The Puzzling Persistence of "Don't Ask, Don't Tell"" 13 May 2009. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/99. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/99 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Puzzling Persistence of "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" Keywords gay rights, military, Social Sciences, Political Science, Rogers Smith, Smith Rogers Disciplines American Politics This article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/99 THE PUZZLING PERSISTENCE OF “DON’T ASK, DON’T TELL” Elizabeth King Advisor: Rogers Smith Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………………………3 CHAPTER ONE Politics and Partisanship in Washington: The Power of the Republican Party …………8 CHAPTER TWO Military Bureaucratic Inertia and the Corresponding Allegiance of the Pentagon ……..27 CHAPTER THREE The Military: An Active and “Passive” Source of Resistance …………………………44 CHAPTER FOUR The Ironic Implications of the War ……………………………………………………...63 Chapter FIVE The Obama Administration and Future of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” …………………..78 CONCLUSION …………………………………………………………………………..90 ADDENDUM …………………………………………………………………………..97 WORKS CITED ……………………………………………………………………….100 2 INTRODUCTION In 1993 President Clinton signed into Public Law 103-160 the statute enacting Sec.654. Policy concerning homosexuality in the armed forces .1 Known as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” it became the first federal law to prohibit gays and lesbians from serving in the United States military officially. -

Reconciling Race, Religion, Media and Democracy in the Quest for Marriage Equality Anthony E

University of Miami Law School University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository Articles Faculty and Deans 2010 Taking Initiatives: Reconciling Race, Religion, Media and Democracy in the Quest for Marriage Equality Anthony E. Varona University of Miami School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/fac_articles Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Anthony E. Varona, Taking Initiatives: Reconciling Race, Religion, Media and Democracy in the Quest for Marriage Equality, 19 Colum. J. Gender & L. 805 (2010). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Deans at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 19.3 Columbia Journal of Gender and Law TAKING INITIATIVES: RECONCILING RACE, RELIGION, MEDIA AND DEMOCRACY IN THE QUEST FOR MARRIAGE EQUALITY ANTHONY E. VARONA 1 Election Days 2008 and 2009 proved to be largely disappointing ones for gay 2 rights advocates, and specifically supporters of civil same-sex marriage rights in the United States. Although Election Day 2008 brought the historic civil rights milestone of the election of the first African American president, it also brought with it the passage of statewide ballot initiatives targeting the gay and lesbian minority in four states. -

Silver Number Integrated Database

ID Program name date Guests Tape # program contents Quotes 2 Hardball w/Chris Matthews June 26, 2002 2188 Y Pledge of Allegiance Vouchers, Judicial Nominations, Armageddon, Apocalypse, Christian 3 Harball w/Chris Matthews June 28, 2002 Orin Hatch, Bob Barr, Ralph Reed 2188 Y Fundamentalism, Israel 4 Hannity and Colmes June 26, 2002 Newt Gingrich 2187 Y Judicial Nominations, Pledge of Allegiance 5 Crossfire June 26, 2002 Rev. Barry Lynn, Lou Sheldon Pledge of Allegiance, September 11th, 2001 6 700 Club June 27, 2002 Pat Robertson, Pledge of Allegiance, Anti-Gay, Jay Sekulow of ACLJ, Gloria Feldt of 7 O'Reilly Factor June 28, 2002 Planned Parenthood 2189 Y Pledge of Allegiance, Reproductive Rights 8 Hannity and Colmes June 28, 2002 Pat Robertson 2187 Y Israel, Armageddon 9 O'Reilly Factor July 3, 2002 Charles Rangel, Joan Garry of GLAAD 2189 Y Anti-Gay, School Vouchers, PFAW mention (referencing her want to see original PFAW press 10 Hardball w/Chris Matthews July 3, 2002 Ann Coulter 2188 Y releases on Bork) Sandy Rios of CWA and Kim Gandy of 11 Crossfire July 3, 2002 NOW Marriage incentive for welfare benefits. 12 700 Club July 3, 2002 Anti-Islamic statements, ACLU and anti-American, September 11th, Richard Thompson of Thomas More Law Anti-Islamic sentiment, suit against Exelcior School (middle school) in 13 O'Reilly Factor July 9, 2002 Center 2189 Y CA Anti-Islamic sentiment: The culture is very clear from 9.11. This is not James Yacovelli of Family Policy about culture. The culture is to kill the infidels and drive planes into us 14 Hannity and Colmes July 9, 2002 Network 2187 Y and blow us up. -

Kenneth B. Mehlman Et Al

Nos. 17-1618, 17-1623, 18-107 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States _______________ GERALD LYNN BOSTOCK, Petitioner, v. CLAYTON COUNTY, GEORGIA, Respondent. _______________ ALTITUDE EXPRESS, INC., AND RAY MAYNARD, Petitioners, v. MELISSA ZARDA AND WILLIAM MOORE, JR., CO-INDEPENDENT EXECUTORS OF THE ESTATE OF DONALD ZARDA Respondents. _______________ R.G. & G.R. HARRIS FUNERAL HOMES, INC., Petitioner, v. EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION AND AIMEE STEPHENS, Respondents. _______________ On Writs of Certiorari to the United States Courts of Appeals for the Eleventh, Second, and Sixth Circuits _______________ BRIEF OF KENNETH B. MEHLMAN ET AL. AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF THE EMPLOYEES _______________ ROY T. ENGLERT, JR. Counsel of Record LAURIE R. RUBENSTEIN PETER A. GABRIELLI CAROLYN M. FORSTEIN ROBBINS, RUSSELL, ENGLERT, ORSECK, UNTEREINER & SAUBER LLP 2000 K STREET NW 4TH FLR WASHINGTON, DC 20006 (202) 775-4500 [email protected] i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ..................................... ii INTEREST OF THE AMICI CURIAE .................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................. 2 ARGUMENT ............................................................ 5 I. THE PLAIN TEXT OF TITLE VII PROHIBITS DISCRIMINATION BECAUSE OF AN INDIVIDUAL EMPLOYEE’S SEXUAL ORIENTATION OR TRANSGENDER STATUS .......................... 5 A. Discrimination Because of Sexual Orientation or Transgender Status Necessarily Constitutes Discrimination Because of Sex ................ 6 B. Congressional “Intent” Does Not Override Unambiguous Text ................. 10 C. Title VII Prohibits Discrimination Against Individuals, Rather than Against Protected Classes at Large....... 15 II. PAST PRACTICE DOES NOT REQUIRE A CONTRARY RESULT ...................................... 22 CONCLUSION ....................................................... 24 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases Barnes v. Train, No. 1828-73, 1974 WL 10628 (D.D.C. Aug. 9, 1974), rev’d sub nom. -

Bold Proclamation

William Butte Page A Gay Voice in the Mainstream Press 12 December 2, 2002 www.ExpressGayNews.com Volume 3, Number 41 BOLD PROCLAMATION President Speaks Out on AIDS as Protestors March at White House By Norm Kent Protestors in Washington, with cardboard skulls, and others Publisher D.C., however, were not buying reading, “Stops AIDS Deaths President George W. Bush, amid into the president’s concern. On Now.” Paul Davis, 33, said, “Bush criticism from the creator of the National Nov. 27, several hundred AIDS is without a plan. He has not kept AIDS Quilt and activists that he is not doing activists marched in the nation’s his promises.” He asked that the enough, has issued a national proclamation capital to ask that the president go administration commit five times commemorating World AIDS Day, Dec. 1, further in funding. It was a spirited as much money to the global fight 2002. protest that ended with planned against the pandemic. Declaring that HIV/AIDS is a arrests in front of the White House. The president did not address “pandemic” that has taken the lives of more In a scenario agreed on with the protestors. His AIDS Day than 20 million people and “is projected to police ahead of time, 31 protestors, proclamation stated however, “By take millions more,” President Bush stated, some linked by thin chains around raising awareness and promoting “We must call upon the compassion, energy their waists, lay on their backs on acceptance of people living with and generosity of all people” to rid the world the sidewalk outside the White HIV/AIDS, we help improve the of the disease. -

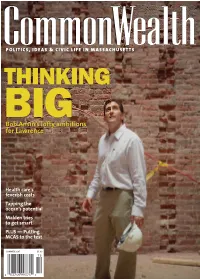

THINKING BIG Bob Ansin’S Lofty Ambitions for Lawrence

POLITICS, IDEAS & CIVIC LIFE IN MASSACHUSETTS THINKING BIG Bob Ansin’s lofty ambitions for Lawrence Health care’s feverish costs Tapping the ocean’s potential Malden tries to get smart PLUS — Putting MCAS to the test SUMMER 2007 $5.00 The Schott Foundation for Public Education is pleased to welcome Dr. John H. Jackson as its New President and CEO On July 2, 2007, Dr. John H. Jackson will officially begin leading The Schott Foundation for Public Education. He is uniquely well suited to take the Foundation’s mission to the next level. He joins The Schott Foundation after serving in leadership positions at the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) since 2000. He served as the NAACP Chief Policy Officer and prior to that as the NAACP’s National Director of Education. Before joining the NAACP, Dr. Jackson served as Senior Policy Advisor in the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) at the U.S. Department of Education during the Clinton Administration. He is also founder and chairman of the National Equity Center Inc., a national non-profit established to promote diversity and democratic val- ues by providing youth with leadership, academic, research and advocacy skills to eliminate existing local and national civil rights and social justice disparities. To learn more about Schott’s new President, please visit our website: www.schottfoundation.org. FAIRNESS, OPPORTUNITY, ACCESS About The Schott Foundation for Public Education Winner of the Council on Foundations’ 2007 Critical Impact Award, The Schott Foundation for Public Education provides and promotes grant- making, strategic convenings and planning, and donor collaborations to develop and strengthen a broad-based and representative movement to achieve high quality, fully funded pre-K through grade 12 public educa- tion in Massachusetts and New York. -

Exploring Queer Conservatism Austin P

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2018 Blurring the Spectrum: Exploring Queer Conservatism Austin P. Mejdrich Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Political Science at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Mejdrich, Austin P., "Blurring the Spectrum: Exploring Queer Conservatism" (2018). Masters Theses. 3736. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3736 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TheGraduate School� E:AsmN�U.MRSJTY- Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution ofThesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. •The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 108 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 108 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 150 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 2004 No. 121 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was last day’s proceedings and announces S. 2639. An act to reauthorize the Congres- called to order by the Speaker pro tem- to the House his approval thereof. sional Award Act. pore (Mr. MILLER of Florida). Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- S. Con. Res. 110. Concurrent resolution ex- nal stands approved. pressing the sense of Congress in support of f the ongoing work of the Organization for Se- DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER f curity and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) in PRO TEMPORE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE combating anti-Semitism, racism, xeno- phobia, discrimination, intolerance, and re- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the lated violence. gentleman from Wisconsin (Mr. KIND) fore the House the following commu- f nication from the Speaker: come forward and lead the House in the WELCOMING THE REVEREND WASHINGTON, DC, Pledge of Allegiance. September 30, 2004. Mr. KIND led the Pledge of Alle- WILLIAM ALVEY I hereby appoint the Honorable JEFF MIL- giance as follows: (Mr. LATOURETTE asked and was LER to act as Speaker pro tempore on this I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the given permission to address the House day. United States of America, and to the Repub- for 1 minute and to revise and extend J. DENNIS HASTERT, lic for which it stands, one nation under God, his remarks.) Speaker of the House of Representatives.