"Keeping Things Shipshape", Conservation Management on HMS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IWM Digital Resource for Volunteers

IWM Digital Resource for Volunteers An Interactive Qualifying Project Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by: Linda Baker Shintaro Clanton Andrew Gregory Rachel Plante Project advisors: VJ Manzo Jianyu Liang June 23, 2016 This report represents the work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of completion of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. ABSTRACT The Interaction Volunteers at Imperial War Museums London engage with visitors in the exhibits and discuss about certain artifacts. The communication of information among the Interaction Volunteer team, however, has been inefficient as the system relied on paper resources. Our IQP team surveyed volunteers and conducted a focus group to gather input about layout and features for a potential digital resource which the Interaction Volunteers could use in management of artifactual content and digital forms. This information was then used to design a website utilizing a content management system in order to make the communication of information more simple and efficient for the Interaction Volunteer team. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Our team would like to thank our advisors, Professors V.J. Manzo and Jianyu Liang, for their continued support and guidance in completing this project. We would especially like to thank Mr. Grant Rogers, Informal Learning and Engagement Manager at Imperial War Museums London, for sponsoring and providing insight for our project and for sharing his enthusiasm for the museum. In addition, we would like to extend our gratitude to the Learning and Engagement Department and Digital Design Department at Imperial War Museums London, for providing us the resources we needed to complete our project, and to the Volunteer Program at Imperial War Museums London for their advice and participation in our project. -

Event Planner Guide 2020 Contents

EVENT PLANNER GUIDE 2020 CONTENTS WELCOME TEAM BUILDING 17 TRANSPORT 46 TO LONDON 4 – Getting around London 48 – How we can help 5 SECTOR INSIGHTS 19 – Elizabeth Line 50 – London at a glance 6 – Tech London 20 – Tube map 54 – Financial London 21 – Creative London 22 DISCOVER – Medical London 23 YOUR LONDON 8 – Urban London 24 – New London 9 – Luxury London 10 – Royal London 11 PARTNER INDEX 26 – Sustainable London 12 – Cultural London 14 THE TOWER ROOM 44 – Leafy Greater London 15 – Value London 16 Opening its doors after an impressive renovation... This urban sanctuary, situated in the heart of Mayfair, offers 307 contemporary rooms and suites, luxurious amenities and exquisite drinking and dining options overseen by Michelin-starred chef, Jason Atherton. Four flexible meeting spaces, including a Ballroom with capacity up to 700, offer a stunning setting for any event, from intimate meetings to banquet-style 2 Event Planner Guide 2020 3 thebiltmoremayfair.com parties and weddings. WELCOME TO LONDON Thanks for taking the time to consider London for your next event. Whether you’re looking for a new high-tech So why not bring your delegates to the capital space or a historic building with more than and let them enjoy all that we have to offer. How we can help Stay connected Register for updates As London’s official convention conventionbureau.london conventionbureau.london/register: 2,000 years of history, we’re delighted to bureau, we’re here to help you conventionbureau@ find out what’s happening in introduce you to the best hotels and venues, Please use this Event Planner Guide as a create a world-class experience for londonandpartners.com London with our monthly event as well as the DMCs who can help you achieve practical index and inspiration – and contact your delegates. -

Imperial War Museum Annual Report and Accounts 2019-20

Imperial War Museum Annual Report and Accounts 2019-20 Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 9(8) Museums and Galleries Act 1992 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 7 October 2020 HC 782 © Crown copyright 2020 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at: www.gov.uk/official-documents. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] ISBN 978-1-5286-1861-8 CCS0320330174 10/20 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office 2 Contents Page Annual Report 1. Introduction 4 2. Strategic Objectives 5 3. Achievements and Performance 6 4. Plans for Future Periods 23 5. Financial Review 28 6. Staff Report 31 7. Environmental Sustainability Report 35 8. Reference and Administrative Details of the Charity, 42 the Trustees and Advisers 9. Remuneration Report 47 10. Statement of Trustees’ and Director-General’s Responsibilities 53 11. Governance Statement 54 The Certificate and Report of the Comptroller and Auditor 69 General to the Houses of Parliament Consolidated Statement of Financial Activities 73 The Statement of Financial Activities 74 Consolidated and Museum Balance Sheets 75 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 76 Notes to the financial statements 77 3 1. -

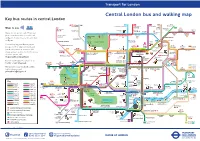

Key Bus Routes in Central London

Route 8 Route 9 Key bus routes in central London 24 88 390 43 to Stoke Newington Route 11 to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to to 73 Route 14 Hill Fields Archway Friern Camden Lock 38 Route 15 139 to Golders Green ZSL Market Barnet London Zoo Route 23 23 to Clapton Westbourne Park Abbey Road Camden York Way Caledonian Pond Route 24 ZSL Camden Town Agar Grove Lord’s Cricket London Road Road & Route 25 Ground Zoo Barnsbury Essex Road Route 38 Ladbroke Grove Lisson Grove Albany Street Sainsbury’s for ZSL London Zoo Islington Angel Route 43 Sherlock Mornington London Crescent Route 59 Holmes Regent’s Park Canal to Bow 8 Museum Museum 274 Route 73 Ladbroke Grove Madame Tussauds Route 74 King’s St. John Old Street Street Telecom Euston Cross Sadler’s Wells Route 88 205 Marylebone Tower Theatre Route 139 Charles Dickens Paddington Shoreditch Route 148 Great Warren Street St. Pancras Museum High Street 453 74 Baker Regent’s Portland and Euston Square 59 International Barbican Route 159 Street Park Centre Liverpool St Street (390 only) Route 188 Moorgate Appold Street Edgware Road 11 Route 205 Pollock’s 14 188 Theobald’s Toy Museum Russell Road Route 274 Square British Museum Route 390 Goodge Street of London 159 Museum Liverpool St Route 453 Marble Lancaster Arch Bloomsbury Way Bank Notting Hill 25 Gate Gate Bond Oxford Holborn Chancery 25 to Ilford Queensway Tottenham 8 148 274 Street Circus Court Road/ Lane Holborn St. 205 to Bow 73 Viaduct Paul’s to Shepherd’s Marble Cambridge Hyde Arch for City Bush/ Park Circus Thameslink White City Kensington Regent Street Aldgate (night Park Lane Eros journeys Gardens Covent Garden Market 15 only) Albert Shaftesbury to Blackwall Memorial Avenue Kingsway to Royal Tower Hammersmith Academy Nelson’s Leicester Cannon Hill 9 Royal Column Piccadilly Circus Square Street Monument 23 Albert Hall Knightsbridge London St. -

IWM-HMS-Belfast-Brochure.Pdf

WELCOME ABOARD There are certain occasions The Admiral’s Quarters which demand special Capacity: Minimum 18 / Maximum 20 (Subject to package) Comprising the original Dining Room and Lounge area of the Admiral’s own living quarters, treatment, where the the Admiral’s Quarters are the perfect space for both boardroom meetings and elegant dining. Restored to reflect how the space would have looked during the 1950’s, the choice of venue is crucial. Admiral’s Quarters provide a luxurious and intimate space for events. Seldom will you find one as unique as HMS Belfast. The Morgan Giles Room Capacity: Minimum 35 / Maximum 90 (Subject to package) Ideal for private dining, meetings, product launches, weddings, receptions and parties, HMS Belfast This room once served as an Officers’ mess and so includes a bar. Named after the UNIQUE Admiral who served in her and later was responsible for ensuring the ship was offers spectacular 360 degree views of London and authentically decorated rooms, each with their own saved from the scrap yard, the room has been restored to reflect the original individual characteristics. Guests can dine in the 1950’s décor and its wood panelled walls echo the camaraderie that was such a SPACES vital part of life on board this great ship. Officers’ Mess, climb a gun turret or watch the sun set on the Quarterdeck. CONFERENCES • MEETINGS DINING • PARTIES • SOCIAL OCCASIONS Permanently moored between London Bridge and The Ward & Ante Room Tower Bridge, HMS Belfast is the most significant Capacity: Minimum 30 / Maximum 100 (Subject to package) surviving Second World War Royal Navy warship. -

Buses from North Greenwich Bus Station

Buses from North Greenwich bus station Route finder Day buses including 24-hour services Stratford 108 188 Bus Station Bus route Towards Bus stops Russell Square 108 Lewisham B for British Museum Stratford High Street Stratford D Carpenters Road HOLBORN STRATFORD 129 Greenwich C Holborn Bow River Thames 132 Bexleyheath C Bromley High Street 161 Chislehurst A Aldwych 188 Russell Square C for Covent Garden Bromley-by-Bow and London Transport Museum 422 Bexleyheath B River Thames Coventry Cross Estate The O2 472 Thamesmead A Thames Path North CUTTER LANE Greenwich 486 Bexleyheath B Waterloo Bridge Blackwall Tunnel Pier Emirates East india Dock Road for IMAX Cinema, London Eye Penrose Way Royal Docks and Southbank Centre BLACKWALL TUNNEL Peninsula Waterloo Square Pier Walk E North Mitre Passage Greenwich St George’s Circus D B for Imperial War Museum U River Thames M S I S L T C L A E T B A N I Elephant & Castle F ON N Y 472 I U A W M Y E E Thamesmead LL A Bricklayers Arms W A S Emirates Air Line G H T Town Centre A D N B P Tunnel Y U A P E U R Emirates DM A A S E R W K Avenue K S S Greenwich Tower Bridge Road S T A ID Thamesmead I Y E D Peninsula Crossway Druid Street E THAMESMEAD Bermondsey Thamesmead Millennium Way Boiler House Canada Water Boord Street Thamesmead Millennium Greenwich Peninsula Bentham Road Surrey Quays Shopping Centre John Harris Way Village Odeon Cinema Millennium Primary School Sainsbury’s at Central Way Surrey Quays Blackwall Lane Greenwich Peninsula Greenwich Deptford Evelyn Street 129 Cutty Sark WOOLWICH Woolwich -

Annual Review 2016/17

Historic Royal Places – Spines Format A4 Portrait Spine Width 35mm Spine Height 297mm HRP Text 20pt (Tracked at +40) Palace Text 30pt (Tracked at -10) Icon 20mm Wide (0.5pt/0.25pt) Annual Review 2016/17 1 2 06 Welcome to another chapter in our story Contents 07 Our work is guided by four principles 08 Chairman’s Introduction 09 Chief Executive – a reflection 10 The Year of the Gardens 14 Guardianship 20 Showmanship 26 Discovery 32 Independence 38 Money matters 39 Visitor trends 40 Summarised financial statements 42 Trustees and Directors 44 Supporters 46 Acknowledgments Clockwise from top left: The White Tower, Tower of London; the West Front, Hampton Court Palace; the East Front, Kensington Palace; the South Front, Hillsborough Castle; Kew Palace; Banqueting House. 4 This year, the famous gardens of Hampton Court Palace took Guardianship: Welcome to centre stage. Already a huge attraction in their own right, this Our work is We exist for tomorrow, not just for yesterday. Our job is to give year the historic gardens burst into even more vibrant life. these palaces a future as valuable as their past. We know how another Prompted by the 300th anniversary of the birth of Lancelot guided by four precious they and their contents are, and we aim to conserve ‘Capability’ Brown, we created a spectacular programme of them to the standard they deserve: the best. chapter in exhibitions, events and activities. A highlight was the royal principles Discovery: opening of the Magic Garden; our playful and spectacular We explain the bigger picture, and then encourage people to our story 21st century contribution to 500 years of garden history. -

21, 2017 Hosted by Harney & Sons Tea + Onward

HARNEY & SONS TEA IN LONDON A Tea Lover’s Adventure in the United Kingdom September 15 — 21, 2017 Hosted by Harney & Sons Tea + Onward Travel harney & sons tea in london 2017 Join the Harney family for a one of a kind tea-centered tour of greater London. Harney & Sons Tea is served at some of the most important tea drinking destinations in the British capital, including the famous Dorchester Hotel and the Historic Royal Palaces. Speaking about Imagine yourself… Britain, George Orwell once said, “Tea is one of the mainstays of the civilization of this country!” Enjoying champagne high tea at the legendary And Orwell was right: nobody drinks tea like the Brits! They average at least Dorchester Hotel three cups per day, encouraged by a wonderful tea drinking culture that has flourished there since the national beverage was made fashionable by King Charles in the 17th century. Today tea is a part of local custom, vernacular, way of life and pop culture at every level of society. Touring a selection of In London, take a day-long Tea Infusiast Masterclass at the UK Tea Academy, Royal gardens enjoy a historic walking tour including visits to Royal residences, and enjoy the traditional British tea service everywhere from the posh Dorchester Hotel to below the copper hull of The Cutty Sark. We’ll trace the history of tea and the tea industry from China to India to the British table. It’s difficult to Learning from one of the seek out tea history in the UK without taking some time to explore another world’s most celebrated quintessentially British pursuit of pleasure: the garden. -

The Cutty Sark

P a g e | 1 THE CUTTY SARK The “Cutty Sark” was a British clipper ship, aptly named of course as a [clipper for its speed1], which was built in 1869 on the [river Clyde in Scotland2] by the Jock Willis Shipping Corporation.3 It was primarily used to transport tea from China to Great Britain, as well to a lesser extent later in its life, wool from Australia;4 however, with the advent of the steam engines and the creation also of the Suez Canal in 1869, its days of operation as a sailing vessel were numbered, as the steam ships were now prevailing as technologically advanced cargo carriers through the shorter route by the Suez Canal to China. In fact, within a few years of its operation, as its delegation in the tea industry was declining, it was assigned primarily the duty of transporting wool from Australia to England, but this activity was thwarted again by the steam ships, as they were enabled by their technologies to travel faster to Australia. Eventually, the “Cutty Sark” in 1895 was sold to a Portuguese company called “Ferreira and Co.”, where it continued to operate as a cargo ship until 1922, when it was purchased on that year by the retired sea captain Wilfred Dowman, who used it as a training ship in the town of Falmouth in Cornwall. After his death, the ship was conferred as a gesture of good will to the “Thames Nautical Training College” in Greenhithe in 1938, where it became an 1 “Clipper – Wikipedia, the free encyclopaedia” – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clipper, 2013: p.1. -

By Mike Klozar Have You Dreamed of Visiting London, but Felt It Would

By Mike Klozar Have you dreamed of visiting London, but felt it would take a week or longer to sample its historic sites? Think again. You can experience some of London's best in just a couple of days. Day One. • Thames River Walk. Take a famous London Black Cab to the Tower of London. The ride is an experience, not just a taxi. (15-30 min.) • Explore the Tower of London. Keep your tour short, but be sure to check out the Crown Jewels. (1-2 hrs.) • Walk across the Tower Bridge. It's the fancy blue one. (15 min.) From here you get the best view of the Tower of London for photos. • Cross over to Butler's Wharf and enjoy lunch at one of the riverfront restaurants near where Bridget lived in Bridget Jones's Diary. (1.5 hrs.) • Keeping the Thames on your right, you'll come to the warship HMS Belfast. Tours daily 10 a.m.-4 p.m. (30 min.-1 hr.) • Walk up London Bridge Street to find The Borough Market. Used in countless films, it is said to be the city's oldest fruit and vegetable market, dating from the mid-1200s. (1 hr.) • Back on the river, you'll discover a tiny ship tucked into the docks: a replica of Sir Francis Drake's Golden Hind, which braved pirates in the days of yore. (15 min.) • Notable London pubs are situated along the route and are good for a pint, a cup of tea and a deserved break. Kids are welcome. -

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

Never-Before-Seen Documents Reveal IWM's Plan for Evacuating Its Art

Never-before-seen documents reveal IWM’s plan for evacuating its art collection during the Second World War Never-before-seen documents from Imperial War Museums’ (IWM) collections will be displayed as part of a new exhibition at IWM London, uncovering how cultural treasures in British museums and galleries were evacuated and protected during the Second World War. The documents, which include a typed notice issued to IWM staff in 1939, titled ‘Procedure in the event of war,’ and part of a collection priority list dated 1938, are among 15 documents, paintings, objects, films and sculptures that will be displayed as part of Art in Exile (5 July 2019 – 5 January 2020). At the outbreak of the Second World War, a very small proportion of IWM’s collection was chosen for special evacuation, including just 281works of art and 305 albums of photographs. This accounted for less than 1% of IWM’s entire collection and 7% of IWM’s art collection at the time, which held works by prominent twentieth- century artists including William Orpen, John Singer Sargent, Paul Nash and John Lavery. Exploring which works of art were saved and which were not, Art in Exile will examine the challenges faced by cultural organisations during wartime. With the exodus of Britain’s cultural treasures from London to safety came added pressures on museums to strike a balance between protecting, conserving and displaying their collections. The works on IWM’s 1938 priority list, 60 of which will be reproduced on one wall in the exhibition, were destined for storage in the country homes of IWM’s Trustees, where it was believed German bombers were unlikely to venture.