Icon, Representation and Virtuality in Reading the Graphic Narrative David Steiling University of South Florida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Ahead of Their Time

NUMBER 2 2013 Ahead of Their Time About this Issue In the modern era, it seems preposterous that jazz music was once National Council on the Arts Joan Shigekawa, Acting Chair considered controversial, that stream-of-consciousness was a questionable Miguel Campaneria literary technique, or that photography was initially dismissed as an art Bruce Carter Aaron Dworkin form. As tastes have evolved and cultural norms have broadened, surely JoAnn Falletta Lee Greenwood we’ve learned to recognize art—no matter how novel—when we see it. Deepa Gupta Paul W. Hodes Or have we? When the NEA first awarded grants for the creation of video Joan Israelite Maria Rosario Jackson games about art or as works of art, critical reaction was strong—why was Emil Kang the NEA supporting something that was entertainment, not art? Yet in the Charlotte Kessler María López De León past 50 years, the public has debated the legitimacy of street art, graphic David “Mas” Masumoto Irvin Mayfield, Jr. novels, hip-hop, and punk rock, all of which are now firmly established in Barbara Ernst Prey the cultural canon. For other, older mediums, such as television, it has Frank Price taken us years to recognize their true artistic potential. Ex-officio Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) In this issue of NEA Arts, we’ll talk to some of the pioneers of art Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) Rep. Betty McCollum (D-MN) forms that have struggled to find acceptance by the mainstream. We’ll Rep. Patrick J. Tiberi (R-OH) hear from Ian MacKaye, the father of Washington, DC’s early punk scene; Appointment by Congressional leadership of the remaining ex-officio Lady Pink, one of the first female graffiti artists to rise to prominence in members to the council is pending. -

Art Spiegelman's Experiments in Pornography

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Art Spiegelman’s ‘Little Signs of Passion’ and the Emergence of Hard-Core Pornographic Feature Film AUTHORS Williams, PG JOURNAL Textual Practice DEPOSITED IN ORE 20 August 2018 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/33778 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Art Spiegelman’s ‘Little Signs of Passion’ and the emergence of hard-core pornographic feature film Paul Williams In 1973 Bob Schneider and the underground comix1 creator Art Spiegelman compiled Whole Grains: A Book of Quotations. One of the aphorisms included in their book came from D. H. Lawrence: ‘What is pornography to one man is the laughter of genius to another’.2 Taking a cue from this I will explore how Spiegelman’s comic ‘Little Signs of Passion’ (1974) turned sexually explicit subject matter into an exuberant narratological experiment. This three-page text begins by juxtaposing romance comics against hard-core pornography,3 the former appearing predictable and artificial, the latter raw and shocking, but this initial contrast breaks down; rebutting the defenders of pornography who argued that it represented a welcome liberation from repressive sexual morality, ‘Little Signs of Passion’ reveals how hard-core filmmakers turned fellatio and the so-called money shot (a close-up of visible penile ejaculation) into standardised narrative conventions yielding lucrative returns at the box office. -

Chris Ware's Jimmy Corrigan

Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan : Honing the Hybridity of the Graphic Novel By DJ Dycus Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan : Honing the Hybridity of the Graphic Novel, by DJ Dycus This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by DJ Dycus All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-3527-7, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-3527-5 For my girls: T, A, O, and M TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures............................................................................................. ix CHAPTER ONE .............................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION TO COMICS The Fundamental Nature of this Thing Called Comics What’s in a Name? Broad Overview of Comics’ Historical Development Brief Survey of Recent Criticism Conclusion CHAPTER TWO ........................................................................................... 33 COMICS ’ PLACE WITHIN THE ARTISTIC LANDSCAPE Introduction Comics’ Relationship to Literature The Relationship of Comics to Film Comics’ Relationship to the Visual Arts Conclusion CHAPTER THREE ........................................................................................ 73 CHRIS WARE AND JIMMY CORRIGAN : AN INTRODUCTION Introduction Chris Ware’s Background and Beginnings in Comics Cartooning versus Drawing The Tone of Chris Ware’s Work Symbolism in Jimmy Corrigan Ware’s Use of Color Chris Ware’s Visual Design Chris Ware’s Use of the Past The Pacing of Ware’s Comics Conclusion viii Table of Contents CHAPTER FOUR ....................................................................................... -

The Graphic Novel, a Special Type of Comics

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02523-3 - The Graphic Novel: An Introduction Jan Baetens and Hugo Frey Excerpt More information Introduction: The Graphic Novel, 1 a Special Type of Comics Is there really something like the graphic novel? For good or ill, there are famous quotations that are frequently repeated when discussing the graphic novel. They are valued because they come from two of the key protagonists whose works from the mid-1980s were so infl uential in the concept gaining in popularity: Art Spiegelman, the creator of Maus , and Alan Moore, the scriptwriter of Watchmen . Both are negative about the neologism that was being employed to describe the longer-length and adult-themed comics with which they were increas- ingly associated, although their roots were with underground comix in the United States and United Kingdom, respectively. Spiegelman’s remarks were fi rst published in Print magazine in 1988, and it was here that he suggested that “graphic novel” was an unhelpful term: The latest wrinkle in the comic book’s evolution has been the so-called “graphic novel.” In 1986, Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns , a full-length trade paperback detailing the adventures of the superhero as a violent, aging vigilante, and my own MAUS, A Survivor’s Tale both met with com- mercial success in bookstores. They were dubbed graphic novels in a bid for social acceptability (Personally, I always thought Nathaniel West’s The 1 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02523-3 - The Graphic Novel: An Introduction Jan Baetens and Hugo Frey Excerpt More information 2 The Graphic Novel: An Introduction Day of the Locust was an extraordinarily graphic novel, and that what I did was . -

Writing About Comics

NACAE National Association of Comics Art Educators English 100-v: Writing about Comics From the wild assertions of Unbreakable and the sudden popularity of films adapted from comics (not just Spider-Man or Daredevil, but Ghost World and From Hell), to the abrupt appearance of Dan Clowes and Art Spiegelman all over The New Yorker, interesting claims are now being made about the value of comics and comic books. Are they the visible articulation of some unconscious knowledge or desire -- No, probably not. Are they the new literature of the twenty-first century -- Possibly, possibly... This course offers a reading survey of the best comics of the past twenty years (sometimes called “graphic novels”), and supplies the skills for reading comics critically in terms not only of what they say (which is easy) but of how they say it (which takes some thinking). More importantly than the fact that comics will be touching off all of our conversations, however, this is a course in writing critically: in building an argument, in gathering and organizing literary evidence, and in capturing and retaining the reader's interest (and your own). Don't assume this will be easy, just because we're reading comics. We'll be working hard this semester, doing a lot of reading and plenty of writing. The good news is that it should all be interesting. The texts are all really good books, though you may find you don't like them all equally well. The essays, too, will be guided by your own interest in the texts, and by the end of the course you'll be exploring the unmapped territory of literary comics on your own, following your own nose. -

Sep CUSTOMER ORDER FORM

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18 FeB 2013 Sep COMIC THE SHOP’S pISpISRReeVV eeWW CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Sep13 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/8/2013 9:49:07 AM Available only DOCTOR WHO: “THE NAME OF from your local THE DOCTOR” BLACK T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! GODZILLA: “KING OF THANOS: THE SIMPSONS: THE MONSTERS” “INFINITY INDEED” “COMIC BOOK GUY GREEN T-SHIRT BLACK T-SHIRT COVER” BLUE T-SHIRT Preorder now! Preorder now! Preorder now! 9 Sep 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 8/8/2013 9:54:50 AM Sledgehammer ’44: blaCk SCienCe #1 lightning War #1 image ComiCS dark horSe ComiCS harleY QUinn #0 dC ComiCS Star WarS: Umbral #1 daWn of the Jedi— image ComiCS forCe War #1 dark horSe ComiCS Wraith: WelCome to ChriStmaSland #1 idW PUbliShing BATMAN #25 CATAClYSm: the dC ComiCS ULTIMATES’ laSt STAND #1 marvel ComiCS Sept13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/8/2013 2:53:56 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Shifter Volume 1 HC l AnomAly Productions llc The Joyners In 3D HC l ArchAiA EntErtAinmEnt llc All-New Soulfire #1 l AsPEn mlt inc Caligula Volume 2 TP l AvAtAr PrEss inc Shahrazad #1 l Big dog ink Protocol #1 l Boom! studios Adventure Time Original Graphic Novel Volume 2: Pixel Princesses l Boom! studios 1 Ash & the Army of Darkness #1 l d. E./dynAmitE EntErtAinmEnt 1 Noir #1 l d. E./dynAmitE EntErtAinmEnt Legends of Red Sonja #1 l d. E./dynAmitE EntErtAinmEnt Maria M. -

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 NOV 2016 NOV COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Nov16 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/6/2016 8:29:09 AM Dark Horse C2.indd 1 9/29/2016 8:30:46 AM SLAYER: CURSE WORDS #1 RELENTLESS #1 IMAGE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS JUSTICE LEAGUE/ POWER RANGERS #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT ANGEL THE FEW #1 SEASON 11 #1 IMAGE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS MY LITTLE PONY: FRIENDSHIP IS MAGIC #50 IDW PUBLISHING THE KAMANDI THE MIGHTY CHALLENGE #1 CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS Nov16 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/6/2016 10:50:56 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Octavia Butler’s Kindred GN l ABRAMS COMICARTS Riverdale #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Uber: Invasion #2 l AVATAR PRESS INC WWE #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Ladycastle #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Unholy #1 l BOUNDLESS COMICS Kiss: The Demon #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Red Sonja #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT James Bond: Felix Leiter #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Psychodrama Illustrated #1 l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 Johnny Hazard Sundays Archive 1944-1946 Full Size Tabloid HC l HERMES PRESS Ghost In Shell Deluxe RTL Volume 1 HC l KODANSHA COMICS Ghost In Shell Deluxe RTL Volume 2 HC l KODANSHA COMICS Voltron: Legendary Defender Volume 1 TP l LION FORGE The Damned Volume 1 GN l ONI PRESS INC. The Rift #1 l RED 5 COMICS Reassignment #1 l TITAN COMICS Assassins Creed: Defiance #1 l TITAN COMICS Generation Zero Volume 1: We Are the Future TP l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC 2 BOOKS Spank: The Art of Fernando Caretta SC l ART BOOKS -

Images of Jewish Women in Comic Books and Graphic Novels. a Master’S Paper for the M.S

Alicia R. Korenman. Princesses, Mothers, Heroes, and Superheroes: Images of Jewish Women in Comic Books and Graphic Novels. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S degree. April 2006. 45 pages. Advisor: Barbara B. Moran This study examines the representations of Jewish women in comic books and graphic novels, starting with a discussion of common stereotypes about Jewish women in American popular culture. The primary sources under investigation include Gilbert Hernandez’s Love and Rockets X, Aline Kominsky-Crumb’s autobiographical works, the X-Men comic books, Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!, Joann Sfar’s The Rabbi’s Cat, and J.T. Waldman’s Megillat Esther. The representations of Jewish women in comic books and graphic novels vary widely. And although certain stereotypes about Jewish women—especially the Jewish Mother and the Jewish American Princess—pervade American popular culture, most of the comics featuring Jewish characters do not seem to have been greatly influenced by these images. Headings: Comic books, strips, etc. -- United States -- History and Criticism Popular Culture -- United States – History – 20th Century Jewish Women -- United States – Social Life and Customs Jews -- United States -- Identity PRINCESSES, MOTHERS, HEROES, AND SUPERHEROES: IMAGES OF JEWISH WOMEN IN COMIC BOOKS AND GRAPHIC NOVELS by Alicia R. Korenman A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina April 2006 Approved by _______________________________________ Barbara B. -

Hastings Public Library

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Libraries Nebraska Library Association 5-2014 Nebraska Libraries - Volume 2, Number 2 (May 2014) Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/neblib Part of the Library and Information Science Commons "Nebraska Libraries - Volume 2, Number 2 (May 2014)" (2014). Nebraska Libraries. 6. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/neblib/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraska Library Association at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Libraries by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. NebraskaLIBRARIES May 2014, Vol. 2, No. 2 The Journal of the Nebraska Library Association NebraskaLIBRARIES May 2014, Volume 2, Number 2 Published by the Nebraska Library Association CONTENTS Membership in NLA is open to any individual or Editor’s Message 3 institution interested in Nebraska libraries. Omaha Public Library’s Common Soil Seed Library 4 To find out more about NLA, write to: Emily Getzschman Nebraska Library Association c/o Executive Director, Michael Straatmann Google Glass in the Library 9 P.O. Box 21756 Jake Rundle Lincoln, NE 68542-1756; Banding Together [email protected] Kim Gangwish, Sara Churchill, Stephanie 11 Schrabel Opinions expressed in Nebraska Libraries are those of Connecting School & Public Libraries 13 the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by Melody Kenney NLA. Random Acts of Kindness 15 Articles in Nebraska Libraries are protected by Rebecca Brooks copyright law and may not be reprinted without prior The Sociology of Knowledge, Technology, and the written permission from the author. -

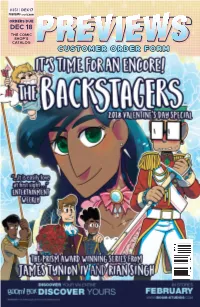

Customer Order Form

#351 | DEC17 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE DEC 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Dec17 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 11/9/2017 3:19:35 PM Dec17 Dark Horse.indd 1 11/9/2017 9:27:19 AM KICK-ASS #1 (2018) INCOGNEGRO: IMAGE COMICS RENAISSANCE #1 DARK HORSE COMICS GREEN LANTERN: EARTH ONE VOLUME 1 HC DC ENTERTAINMENT MATA HARI #1 DARK HORSE COMICS VS. #1 IMAGE COMICS PUNKS NOT DEAD #1 IDW ENTERTAINMENT THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD: BATMAN AND WONDER DOCTOR STRANGE: WOMAN #1 DAMNATION #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS Dec17 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 11/9/2017 3:15:13 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Jimmy’s Bastards Volume 1 TP l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Dreadful Beauty: The Art of Providence HC l AVATAR PRESS INC 1 Jim Henson’s Labyrinth #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS WWE #14 l BOOM! STUDIOS Dejah Thoris #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 Pumpkinhead #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Is This Guy For Real? GN l :01 FIRST SECOND Battle Angel Alita: Mars Chronicle Volume 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS Dead of Winter Volume 1: Good Good Dog GN l ONI PRESS INC. Devilman: The Classic Collection Volume1 GN l SEVEN SEAS ENTERTAINMENT LLC Your Black Friend and Other Strangers HC l SILVER SPROCKET Bloodborne #1 l TITAN COMICS Robotech Archive Omnibus Volume 1 GN l TITAN COMICS Disney·Pixar Wall-E GN l TOKYOPOP Bloodshot: Salvation #6 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC BOOKS Doorway to Joe: The Art of Joe Coleman HC l ART BOOKS Neon Visions: The Comics of Howard Chaykin SC l COMICS Drawing Cute With Katie Cook SC l HOW-TO 2 Action Presidents