Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

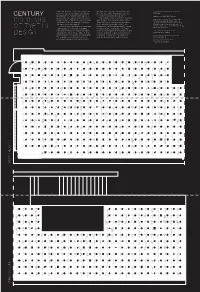

Century 100 Years of Type in Design

Bauhaus Linotype Charlotte News 702 Bookman Gilgamesh Revival 555 Latin Extra Bodoni Busorama Americana Heavy Zapfino Four Bold Italic Bold Book Italic Condensed Twelve Extra Bold Plain Plain News 701 News 706 Swiss 721 Newspaper Pi Bodoni Humana Revue Libra Century 751 Boberia Arriba Italic Bold Black No.2 Bold Italic Sans No. 2 Bold Semibold Geometric Charlotte Humanist Modern Century Golden Ribbon 131 Kallos Claude Sans Latin 725 Aurora 212 Sans Bold 531 Ultra No. 20 Expanded Cockerel Bold Italic Italic Black Italic Univers 45 Swiss 721 Tannarin Spirit Helvetica Futura Black Robotik Weidemann Tannarin Life Italic Bailey Sans Oblique Heavy Italic SC Bold Olbique Univers Black Swiss 721 Symbol Swiss 924 Charlotte DIN Next Pro Romana Tiffany Flemish Edwardian Balloon Extended Bold Monospaced Book Italic Condensed Script Script Light Plain Medium News 701 Swiss 721 Binary Symbol Charlotte Sans Green Plain Romic Isbell Figural Lapidary 333 Bank Gothic Bold Medium Proportional Book Plain Light Plain Book Bauhaus Freeform 721 Charlotte Sans Tropica Script Cheltenham Humana Sans Script 12 Pitch Century 731 Fenice Empire Baskerville Bold Bold Medium Plain Bold Bold Italic Bold No.2 Bauhaus Charlotte Sans Swiss 721 Typados Claude Sans Humanist 531 Seagull Courier 10 Lucia Humana Sans Bauer Bodoni Demi Bold Black Bold Italic Pitch Light Lydian Claude Sans Italian Universal Figural Bold Hadriano Shotgun Crillee Italic Pioneer Fry’s Bell Centennial Garamond Math 1 Baskerville Bauhaus Demian Zapf Modern 735 Humanist 970 Impuls Skylark Davida Mister -

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11. Typeface Broadside/Poster Broadsides have been an aspect of typography and printing since the earliest types. Printers and Typographers would print a catalogue of their available fonts on one large sheet of paper. The introduction of a new typeface would also warrant the issue of a broadside. Printers and Typographers continue to publish broadsides, posters and periodicals to advertise available faces. The Adobe website that you use for research is a good example of this purpose. Advertising often interprets the type creatively and uses the typeface in various contexts to demonstrate its usefulness. Type designs reflect their time period and the interests and experiences of the type designer. Type may be planned to have a specific “look” and “feel” by the designer or subjective meaning may be attributed to the typeface because of the manner in which it reflects its time, the way it is used, or the evolving fashion of design. For this third project, you will create two posters about a specific typeface. One poster will deal with the typeface alone, cataloguing the face and providing information about the type designer. The second poster will present a visual analogy of the typeface, that combines both type and image, to broaden the viewer’s knowledge of the type. Process 1. Research the history and visual characteristics of a chosen typeface. Choose a typeface from the list provided. -Write a minimum150 word description of the typeface that focuses on two themes: A. The historical background of the typeface and a very brief biography of the typeface designer. -

Titling Fonts

Titling Fonts by Ilene Strizver HISTORICALLY, A “titling font” WAS A FONT OF METAL TYPE designed specifically for use at larger point sizes and display settings, including headlines and titles. Titling fonts, a specialized subset of display typefaces, differ from their text counterparts in that their scale, proportion and design details have been modified to look their best at larger sizes. They often have a more pronounced weight contrast (resulting in thinner thins), tighter spacing, and more condensed proportions than their text- sized cousins. Titling fonts may also have distinctive refinements that enhance their elegance and impact. Titling fonts are most often all-cap, single-weight variants created to complement text families, such as the These titling faces are stand-alone designs, rather than part of a larger family. a lowercase; Perpetua Titling has three ITC Golden Cockerel Titling (upper) is more streamlined than its non-titling cousin (lower). weights; and Forum Titling, based on a It also has different finishing details, as shown Frederick Goudy design, has small caps on the serif ending stroke of the C. in three weights that were added later. The overall design of most (but not all) titling fonts designed as part of the titling fonts is traditional or even historic Dante, Plantin, Bembo, Adobe in nature. In the days of metal type, Garamond Pro, and ITC Golden Cockerel titling capital letters took up the full typeface families. point size body height. For example, 48 point Perpetua titling caps were They can also be standalone designs, basically 48 points tall, whereas regular 48 point Perpetua was sized such that Dante Titling (upper) has greater weight such as Felix Titling, Festival Titling, and the tallest ascender and longest contrast and is slightly more condensed than Victoria Titling Condensed. -

İlahiyat Fakültesinin İlmi Dergisi- 18-19. Sayı 2013 44 EDMUND

İlahiyat Fakültesinin İlmi Dergisi- 18-19. Sayı 2013 Oş Devlet Ünıversitesi Ош мамлекеттик университети İlahiyat Fakültesi İlmi Dergisi Теология факультетинин илимий журналы 18-19. sayı 2013 18-19-саны 2013 EDMUND CASTELL’IN HEPTAGLOT SÖZLÜĞÜ ÖRNEĞİNDE ARAPÇA’NIN ÇOK DİLLİ SÖZLÜK GELENEĞİNDEKİ YERİ Yrd. Doç. Dr. Ömer ACAR* Arabic And It’s Place In The Tradition of Multilingual Lexicography In Case of Edmund Castell’s Lexicon Heptaglotton Abstract This study outlines the place of Arabic in the tradition of multilangual dictionary. Especially the levels of the Arabic language dictionary writing that an important part of Arabic studies which in center of European orientalist studies and E. Castell`s voluminous work is the basis of this study. Initially, most of the commercial and economic concerns, multilingual dictionaries prepared in the form of word lists developed important services, especially in the field of translation. The word lists of the Sumer-Babil-Asur languages are considered as ancestor of multilingual dictionaries. As a member of this family Arabic language has an important condition in this area. Keywords: Edmund Castell, Multilingual Dictionaries, Polyglot, Arabic, Word Lists. Önsöz Bu çalışma, Arapçanın çok dilli sözlük geleneği içindeki yerini ana hatlarıyla ele almaktadır. Özellikle Avrupa’da oryantalist çalışmaların merkezinde yer alan Arap dili araştırmalarında önemli bir yere sahip sözlük yazımının geçirdiği merhaleler ve bu alanda türünün ilk örneği kabul edilen E. Castell’a ait Lexicon Heptaglotton adlı hacimli -

THE KING JAMES VERSION of the BIBLE Preface the Bible Is God's Inspired and Infallible Word – It Is God's Book

THE KING JAMES VERSION OF THE BIBLE Preface The Bible is God's inspired and infallible Word – it is God's Book. God has given this Book to His people to teach them the Truth that they must believe and the godly life that they must live. Without the Holy Scriptures the believer has no standard of what is the Truth and what is the lie, what is righteous and what is wicked. It is, therefore, imperative that everyone takes great care that the Bible version that he uses, defends, and promotes in the world is a faithful translation of the Word of God. On this point, however, there is much confusion. There are many versions available today and they are all promoted as the best, the most accurate or the easiest to understand. All of them are justified by the supposed inferiority of the King James Version. The truth is quite different. The King James Version, although it is 400 years old, is still the best translation available today. It was translated by men who were both intellectually and spiritually qualified for the work The great version that they produced is faithful to the originals, accurate, incomparable in its style, and easily understood by all those who are serious about knowing God's Word. The King James Version of the Bible is the version to be used in our churches and in our homes. The Inception Of The New Version: A Puritan's Petition – Representatives of the Church of England were gathered together for a conference in January 1604. -

An Investigation Into the Version That Shaped European Scholarship on the Arabic Bible

Collectanea Christiana Orientalia 18 (2021): 237-259 Vevian Zaki Cataloger of Arabic Manuscripts Hill Museum and Manuscript Library Visiting Researcher Faculty of History University of Oxford The “Egyptian Vulgate” in Europe: An Investigation into the Version that Shaped European Scholarship on the Arabic Bible Introduction In the years from 1818 to 1821, August Scholz (1792–1852), a Catholic orientalist and biblical scholar, made many journeys to libraries across Europe seeking New Testament (NT) manuscripts. He wrote an account of his travels in his book Biblisch-kritische Reise, and in this book, Scholz wrote about all the NT manuscripts he encountered in each library he visited, whether they were in Greek, Latin, Syriac, or Arabic.1 What attracts the attention when it comes to the Arabic NT manuscripts is that he always compared their texts to the text of the printed edition of Erpenius.2 This edition of the Arabic NT was prepared in 1616 by Thomas Erpenius (1584-1624), the professor of Arabic studies at Leiden University—that is, two centuries before the time of Scholz. It was the first full Arabic NT to be printed in Europe, and its text was taken from Near Eastern manuscripts that will be discussed below. Those manuscripts which received particular attention from Scholz were those, such as MS Vatican, BAV, Ar. 13, whose text was rather different from that of Erpenius’s edition.3 1 Johann Martin Augustin Scholz, Biblisch-Kritische Reise in Frankreich, der Schweiz, Italien, Palästina und im Archipel in den Jahren 1818, 1819, 1820, 1821 (Leipzig: Fleischer, 1823). 2 Thomas Erpenius, ed. -

The Word of God

The Word of God REASONS THE KJV IS SUPERIOR Outstanding Credentials of the KJV's Translators Alexander McClure and Gustafus Paine have both written excellent biographies of the men who translated the King James Bible. These biographies document the fact that the KJV translators were scholarly and godly men. They lived separated lives and they were orthodox in doctrine. And all of them showed reverence for the divine authorship of God's Word and God's promise to preserve His Word. The King James Bible was translated by men like Lancelot Andrews who wrote Greek devotionals. Lancelot Andrews was an Oriental language expert. He was conversant in fifteen languages. Most new version translators have had only a couple years of Greek, a couple years of Hebrew and might have taken Spanish or French in high school. Lancelot Andrews was conversant in fifteen languages. Another great man who translated the King James Bible was William Bedwell. Bedwell was an Arabic scholar. He revived the Arabic language. It was about to die, and he literally revived it. William Bedwell wrote an Arabic to English Lexicon. A lexicon is a dictionary that will give the Arabic word and its definition in English. A Greek Lexicon gives the Greek word and its definition in English. William Bedwell wrote the Arabic Lexicon that is still in use today. Go to the library and if they happen to have an Arabic Lexicon it will probably be the one that William Bedwell wrote. Miles Smith also helped to translate the King James Bible. However, he is better known as the man who translated all the writings of the church fathers into English. -

Design One Project Three Introduced March 18. Due April 15. Typeface

Design One Project Three Introduced March 18. Due April 15. Typeface Broadside/Poster Broadsides have been an aspect of typography and printing since the earliest types. Printers and Typographers would print a catalogue of their available fonts on one large sheet of paper. The introduction of a new typeface would also warrant the issue of a broadside. Printers and Typographers continue to publish broadsides, posters and periodicals to advertise available faces. The Adobe website that you use for research is a good example of this purpose. Advertising often interprets the type creatively and uses the typeface in various contexts to demonstrate its usefulness. Type designs reflect their time period and the interests and experiences of the type designer. Type may be planned to have a specific “look” and “feel” by the designer or subjective meaning may be attributed to the typeface because of the manner in which it reflects its time, the way it is used, or the evolving fashion of design. For this third project, you will create two posters about a specific typeface. One poster will deal with the typeface alone, cataloguing the face and providing information about the type designer. The second poster will present a visual analogy of the typeface, that combines both type and image, to broaden the viewer’s knowledge of the type. Process 1. Research the history and visual characteristics of a chosen typeface. Choose a typeface from the list provided. -Write an approximately 150 word description of the typeface that focuses on two themes: A. The historical background of the typeface and a very brief biography of the typeface designer. -

THE WORD in PRINT: Does the King James Bible Have a Future?

The Twenty-sixth ERIC SYMES ABBOTT Memorial Lecture THE WORD IN PRINT: Does the King James Bible Have a Future? delivered by The Rt Revd & Rt Hon Dr Richard Chartres KCVO Bishop of London at Westminster Abbey on Thursday 26 May 2011 and at Keble College, Oxford on Friday 27 May 2011 The Twenty-sixth ERIC SYMES ABBOTT Memorial Lecture THE WORD IN PRINT: Does the King James Bible Have a Future? delivered by The Rt Revd & Rt Hon Dr Richard Chartres KCVO Bishop of London at Westminster Abbey on Thursday 26 May 2011 and at Keble College, Oxford on Friday 27 May 2011 The Eric Symes Abbott Memorial Fund was endowed by friends of Eric Abbott to provide for an annual lecture or course of lectures on spirituality. The lecture is usually given in May on consecutive evenings in London and Oxford. The members of the Committee are: the Dean of King’s College London (Chairman); the Dean of Westminster; the Warden of Keble College, Oxford; the Reverend John Robson; the Reverend Canon Eric James; and the Right Reverend the Lord Harries of Pentregarth. This Lecture is the twenty-sixth in the series, and details of previous lectures may be found overleaf. Booklets of most – although not all – of these lectures are available from the Dean’s Office at King’s College London (contact details as below), priced at 50p per booklet plus 50p postage and packing. Please specify the year, the lecture number, and the lecturer when requesting booklets. Lecture texts for about half the lectures are also available on the Westminster Abbey website (with the intention to have them all available in due course). -

Ag Brand Manual

Ag Brand Manual 1 Ag Visual Identity A guideline for creative talent. “Too much flexibility results in complete chaos, too much structure results in lifeless communications. Balance is the Design Continuity goal.” These guidelines are not intended to provide every All permissions are denied unless detail regarding graphics expressly granted. applications, production processes and standards, but to Guideline Purpose provide general direction for Promote the Ag visual identity in maintaining consistency with the most convenient, consistent the Ag identity. and efficient way and make sure no mistakes are made. ©2011 DECAGON PRINTED IN USA v1.0 2 Heirarchy & Emphasis Typography and colors are palettes. They have a limited number of choices in a given range. They have shades or weight. Type on a page appears as a gray block to the eye. Weight is a degree of boldness or shade. Weight helps the viewer determine what is most important. It creates interest and attractive design. Varying type weights give the illusion of depth to a page. Darker type moves forwards and lighter type receeds. This helps emphasize what elements should be viewed and in what order. These direct the eye of the observer or reader. This is presentation strategy. If everything is emphasied equally, it creates visual noise. “Emphasizing everything equals emphasizing nothing.” —marketing adage. 3 Logo Application The Decagon logo is described as No scanning logo artwork! a stack logo. Word parts of the logotype are not all on the same Logo Placement line. The logo should appear only once on each printed spread (not each The logo sides are sloped (italic). -

The Story of Perpetua

The Story of Perpetua 3 Tiffany Wardle March 10, 2000 2 4 Essay submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Theory and History of Typography and Graphic Communication, University of Reading, 2000. This essay relates the origins of the typeface Perpetua and Felicity italic which were designed by Eric Gill and produced byThe Monotype Corporation.Although the type and the collaborators are well known, the story has had to be pieced together from a variety of sources—Gill’s and Morison’s own writings and biographical accounts.There are accounts similar to this, but none could be found that either takes this point of view, or goes into as great detail. In 1924, an essay directed towards the printers and type founders was calling for a new type for their time. Entitled ‘Towards An Ideal Type,’ Stanley Morison wrote it for the second volume of The Fleuron. In the closing statement there is an appeal for “some modern designer who knows his way along the old paths to fashion a fount of maximum homogeneity, that is to say, a type in which the uppercase, in spite of its much greater angularity and rigidity, accords with the great fellowship of colour and form with the rounder and more vivacious lowercase.”1 Two years later, in 1926, again Morison is requesting a “typography based not upon the needs and conventions of renaissance society but upon those of modern England.”2 Only two years previous had the Monotype Corporation assigned Stanley Morison as their Typographical Advisor. Once assigned he pursued what he later came to call his “programme of typographical design”3 with renewed vigour. -

Westcott and Hort

The Bible’s First Question “YEA, HATH GOD SAID?” (Satan’s question) Genesis 3:1 1 The Bible’s 2nd Question “WHERE ART THOU?” (God’s question) Genesis 3:9 2 Psalm 11:3—Key Verse “If the foundations be destroyed, what can the righteous do?” (Psalm 11:3) The FOUNDATION of ALL DOCTRINE is the BIBLE. Having the RIGHT BIBLE is critically IMPORTANT!! 3 600 Years of English Bible Versions Years Bibles & N.T’s Years Between Undated 1+6 = 7 --------- 1300's 3+1 = 4 25 years 1400's 0+0 = 0 100 years 1500's 11+20 = 31 3.2 years 1600's 5+3 = 8 12.5 years 1700's 17+29 = 46 2.1 years 1800's 45+90 = 135 .74 years 1900's 53+144 = 197 .51 years __________________________________________________ 1300's--1900's 135+293 = 428 1.4 years 4 CHAPTER I God’s Words Kept Intact Is BIBLE PRESERVATION (The Bible’s Timelessness) 5 Verses on Bible Preservation 1. Psalm 12:6-7: “The WORDS of the LORD are pure WORDS: as silver tried in a furnace of earth, purified seven times. Thou shalt KEEP THEM, O LORD, Thou shalt PRESERVE them from this generation FOR EVER.” 2. Psalm 105:8: “He hath remembered His covenant FOR EVER, the WORD which He commanded TO A THOUSAND GENERA- TIONS.” 6 Verses on Bible Preservation 3. Proverbs 22:20-21. “(20) Have not I WRITTEN to thee excellent things in counsels and knowledge, (21) That I might make thee know the CERTAINTY of the WORDS OF TRUTH; that thou mightest answer the WORDS OF TRUTH to them that send unto thee?” 4.