Celebrating the Alcock and Brown Centenary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Library Additions BOOKS

Library Additions BOOKS AERODYNAMICS Distributed by Transatlantic classic first-hand account by South Australia 5031 (https:// UK. 2002. 244pp. Illustrated. Publishers Group, 97 Sir Ross Smith of the epic first www.wakefieldpress.com.au/). ISBN 1-904010-00-8. Flight: and Some of its Greenham Road, London N10 flight to Australia in pursuit of a 2019. 357pp. $29.95 (Aust). Incorporating a number Little Secrets. F M Burrows. 1LN, UK. £116 [20% discount prize of £10,000 – which had ISBN 978-1-74305-663-9. of first-hand recollections, Published by the author, available to RAeS members been announced on 19 March A fictional reconstruction a compilation of concise London. 2017. iv; 322pp. on request; E mark.chaloner@ 1919 by the Australian Prime of the epic first flight to biographies of Air Chief Illustrated. £30. ISBN 978-1- tpgltd.co.uk ] ISBN 978-1- Minister Billy Hughes – for the Australia – the 135 hours 55 Marshal Sir Harry Broadhurst, 79569-651-7. 62410-538-8. first successful Australian- minutes 11,340 mile flight Air Vice-Marshal William Illustrated throughout crewed flight to Australia from of a Vickers Vimy in carefully Crawford-Compton, Squadron with numerous clear colour Both books can also be Great Britain in an aircraft planned stages from England Leader Dave Glaser, Flight diagrams, a well-illustrated purchased as a two-volume made in the British Empire to Australia by Ross and Keith Lieutenant Eric Lock, Flight introduction to the science of set for £165 [20% discount which was to be completed Smith – accompanied by their Lieutenant William ‘Tex’ Ash, fluid dynamics, aerodynamics available to RAeS members within 30 days. -

(Mm&L to ALCOCK and BRO# Cm 15Th JUNE. 1959

.I^MABS^ FOR INDUSTRY AND COMMERCE, WHEN HE_UNVEIL2D A MEMORIAL AT CLIFDEN, CO. (mm&L TO ALCOCK AND BRO# cm 15th JUNE. 1959: - On the roll of pioneers in aviation, from Orville Wright who first took an aeroplane off the ground, to those who are now training to Journey into outer space, are the names of many very brave and enterprising men, and amongst them those of John Alcock and Arthur Whitten-Brown stand out in special prominence - the first men to fly an aeroplane non-stop across the Atlantic. It is fitting that their great enterprise should be marked by an enduring monument at this spot where, on this day forty years ago, they completed their epic journey. This monument with the completion of which Mr. Seamus Murphy, the Cork Sculptor, has been associated is not unworthy of the event. Now, when great aeroplanes fly on regular schedules, over all the wide oceans of the world, it may not be very easy to appreciate the magnitude of the adventure on which Alcock and Brown engaged or measure the great courage for which it called, or even to remember clearly ourselves the great upsurge of pride which was felt by all men everywhere, when the news of their accomplishment was transmitted around the earth. Before they started their flight from Newfoundland, two other daring groups had attempted the hazardous enterprise but had failed. Whatever .confidence Alcock and Brown may have expressed, they could not in their hearts have rated their chance of succeeding very highly, but they were not deterred. -

Press Release

Royal Aeronautical T: +44 (0)20 7670 4300 Society E: [email protected] No. 4 Hamilton Place www.aerosociety.com London W1J 7BQ United Kingdom PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Monday 12 August 2019 Isle of Man Post Office and the Royal Aeronautical Society commemorate a Century of Transatlantic Aviation. The history of transatlantic aviation portrayed in art deco style stamp collection. The Isle of Man Post Office is proud to commemorate a century of achievement in transatlantic aviation to be issued on August 20th 2019. The Art Deco Style stamp collection, created by Glazier Design, showcases the aircraft of the first crossings of the Atlantic in 1919 and a selection of the most significant crossings since. In April 1913 the London newspaper The Daily Mail offered a prize of £10,000 (the equivalent value of over £ 510,000 in 2019) to "the aviator who shall first cross the Atlantic in an aeroplane in flight from any point in United States of America, Canada or Newfoundland to any point in Great Britain or Ireland in 72 continuous hours". Due to the outbreak of World War I in 1914 the competition was suspended but after Armistice was declared in 1918 the race was back on. On 14th June 1919 pilot John Alcock and navigator Arthur Whitten-Brown flew their Vickers Vimy, featured on the Large Letter stamp, in less than 16 hours from St. Johns, Newfoundland to Clifden, County Galway in Ireland and were awarded the Daily Mail prize. Two weeks earlier the Curtis NC-4 (featured on 1st class stamp), a United States Navy flying boat flew from Trepassey Bay, Newfoundland to Lisbon, completing the first crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by air. -

Meet the Mascots

Meet the Mascots Lucky mascots are thought to bring good luck and, over the years, many people in the RAF have had their own special mascots. Find out about some of their fantastic stories and then join in the fun by making your own mascot or puppet. Scotch Jock I served in the First World War as a lucky mascot to my owner Lieutenant W MacLanachan. Some of the pilots even started to look a bit like us teddies. It could get really cold flying aeroplanes, so teddy bear makers used our special woolly material to make flying clothes for the pilots to wear in the air. Twinkletoes On 14 June 1919, I set off on a big adventure with my owner, the navigator Arthur Whitten Brown. My friend Lucky Jim, who is also a black cat, came too. His owner John Alcock, was the pilot of our Vickers Vimy. We went as their lucky mascots … and it must have worked, because after 17 hours they became the first people to cross the Atlantic in an aeroplane. These days, I am looked after by the RAF Museum and the staff at the Science Museum look after Jim. Find out more rafmuseum.org.uk/blog/a-transatlantic-tale collection.sciencemuseum group.org.uk/objects/ co8408130/lucky-jim-toy-cat-mascot-toy Supported by the Royal Air Force Museum American Foundation Gremlins During the Second World War when aircraft didn’t work properly, it was blamed on devilish spirits called gremlins. Of course, these spirit gremlins didn’t really exist but even so, some air crew carried a ‘lucky gremlin’ mascot like me just in case. -

Integrated Free Flight and 4-D Gate-To-Gate Air Traffic Management, Possibilities, Promises and Problems

Nationaal Lucht- en Ruimtevaartlaboratorium National Aerospace Laboratory NLR NLR TP 96239 U Integrated Free Flight and 4-D Gate-to-gate Air Traffic Management, Possibilities, Promises and Problems F.J. Abbink DOCUMENT CONTROL SHEET ORIGINATOR'S REF. SECURITY CLASS. TP 96239 U ORIGINATOR National Aerospace Laboratory NLR, Amsterdam, The Netherlands TITLE INTEGRATED FREE FLIGHT AND 4-D GATE-TO-GATE AIR TRAFFIC MANAGEMENT, POSSIBILITIES, PROMISES AND PROBLEMS PRESENTED AT The 9th European Aerospace Congress "Visions and Limits of Long-term Aerospace Developments", organised by CEAS, Berlin, 14-15 May, 1996. AUTHORS DATE pp ref F.J. Abbink 960404 64 57 DESCRIPTORS Air traffic control Flight safety Airline operations Man-computer interface Automated en route ATC Multisensor applications Automatic landing control Satellite navigation systems Avionics Technology assessment Collision avoidance Warning systems ABSTRACT In the 20th century air transport has developed into a safe, reliable and economic means of transportation for passengers, cargo and mail. In the next two decades, the air transport is forecasted to double. To enable this expansion to occur within the limited airspace, with the limited number of airports and runways and with the increasing requirements with respect to safety, noise and emissions, new technological developments are necessary. The use of satellite-based Communication, Navigation and Surveillance (CNS) systems. combined with further steps towards computer- assisted and automated Air Traffic Management (ATM) with digital datalink between ATM and aircraft computer systems, will be necessary. The introduction of new forward-looking warning systems, the increase of precision on approach and landing systems and the improvement of procedures and training levels will be required to improve the safety level. -

Irondale Newsletter

Irondale Newsletter Produced by the Bark Lake Cultural Developments February / March 2021 Bark Lake Cultural How ‘X’ Came to Mean ‘Kiss’ Developments The idea of using a kiss to sign off on valentines also has a long history. The use of “X” Charitable No. came to represent Christianity, or the cross, in the Middle Ages. 80487 0087 RR0001 The symbol was used to sign off on documents. If you could not sign your name, you Incorporation No. made an X where the signature should be. The writer 1871121 would often kiss the mark as a sign of their oath. Historical As popularity grew, kings and commoners would use it @IrondaleOntario.ca to certify books, letters and paperwork. These records were described as having been “sealed with a kiss.” Host your next function at Irondale’s heritage church Editor’s note—the picture used on the right was taken from the internet as an example. Rental Information & is celebrated in many parts of the world, especially by Irish communities and Newsletter Editor St Patrick’s Day organizations so I thought I would find a few facts to share with you. Carol 705-457-8438 March 17 is actually a religious holiday tho’ most celebrate the Irish culture, customs, food and drink. Irondale Community St. Patrick was one of Ireland’s patron saints, ministered Christianity in Ireland in the fifth Centre century Advisory Committee Luke Wadding (1558-1657) was an Irish Franciscan friar. His persistent efforts turned March of 17 into a ’feast day’. Minden Hills Council Wearing Green - makes you invisible to the Leprechauns - and it is well know than [email protected] Leprechauns like to pinch people. -

Official Journal of the British North America Philatelic Society Volume 26 / Number 9 I Whole Number 283 I October, 1969

D D A Official Journal of the British North America Philatelic Society Vol. 26, No. 9, Whole No. 283 October, 1969 Printed September 25, 1969 New Season ... If there was such a thing as a Philatelic Calendar, New Year's Day would probably fall on September the First. So, Happy New Stamp Year, Everybody I The past year has been a good one for the Stamp Fraternity, Collectors and Dealers alike. There have been many interesting properties • come on the market, and although the competition was strong, the share which we managed to capture contains much worthwhile material which broadens the choice which we can offer to our customers. We will welcome you at 37 Victoria Street if you can get in to look over our new stock, both B.N.A. and the rest of the world. Otherwise your written enquiries w ill get our best attention. ~eorge ~. Wegg JLtb. 37 VICTORIA STREET TORONTO 1 CANADA Telephones: 368-7528 489-1344 Area Code 416 IF YOU THINK SELLING YOUR COLLECTION IS LIKE DIVORCING YOUR WIFE ... you can have custody of the kids!. .. if you'll give us your stamps! Parting with a stamp or coin collection, whatever the reason, Is for most serious collectors, a near traumatic experience. When the time comes, how ever, your collection is in the best of hands at Harmer, Rooke. Whether for auction or for immediate cash from private sale, you can depend on the expertise and professional integrity for which Harmer, Rooke has been famous since 1903. With sophisticated clients throughout the philatelic and numismatic world, Harmer, Rooke Is your assurance of the expeditious liquidation of your col lection at extremely attractive prices. -

'Sadly Forgotten'?: Newspaper Coverage of the First Men to Fly the Atlantic Non-Stop, Alcock and Brown

LJMU Research Online Hodgson, GR 'Sadly forgotten'?: Newspaper coverage of the first men to fly the Atlantic non-stop, Alcock and Brown http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/id/eprint/11796/ Article Citation (please note it is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from this work) Hodgson, GR (2019) 'Sadly forgotten'?: Newspaper coverage of the first men to fly the Atlantic non-stop, Alcock and Brown. Media History, 4 (1). pp. 30-44. ISSN 1368-8804 LJMU has developed LJMU Research Online for users to access the research output of the University more effectively. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LJMU Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. The version presented here may differ from the published version or from the version of the record. Please see the repository URL above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information please contact [email protected] http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/ ‘Sadly Forgotten’? Newspaper coverage of the first men to fly the Atlantic non-stop, Alcock and Brown. On Saturday, June 14, 1919, a Vickers Vimy, a converted First World War bomber powered by two Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines, took off from St John’s, Newfoundland. -

The Coastwatcher Cadets Drilled at Groton New London Airport

ANNUAL CITRUS FRUIT FUND RAISER The selling portion of the fund raiser has ended. Preliminary estimates indicate that approximately Missions for 300 cases were sold. The precise amount will be America reported to the fruit purveyor and we can expect Semper vigilans! delivery in early December. At that time, we will Semper volans! need volunteers to unload the truck. CADET MEETING NOTES 11 November, 2014 The Coastwatcher Cadets drilled at Groton New London Airport. Publication of the Thames River Composite Squadron Cadets were given the opportunity to pass their Connecticut Wing drill tests, and the remainder of the flights Civil Air Patrol practiced marching. 300 Tower Rd., Groton, CT C/MSgt D. Hollingsworth taught a leadership http://ct075.org . lesson on chapter 2 of the Lead to Lead book focusing on “The Cadet and the Team.” LtCol Stephen Rocketto, Editor [email protected] C/2Lt Carter gave a safety briefing on the dangers of floods. C/MSgt Virginia Poe, Reporter C/SrA Michael Hollingsworth, Printer's Devil C/1Lt Tynan presented the cadets with a team Lt David Meers & Maj Roy Bourque, Papparazis building activity designed to teach communication.d. Vol. VIII, No. 41 04 November, 2014 THE MARINES HAVE LANDED SCHEDULE OF COMING EVENT Former Cadet Sean O'Toole visited wearing his new U.S. Marine Corps uniform. O'Toole spoke to cadets. He is awaiting assignment to a Military 08 NOV-CTWG Pilots' Meeting-MMK Occupation Specialty. 08-09 NOV-SLS Course-Meriden 11 NOV-TRCS Meeting 15 NOV-CTWG SAREX-Flight Session 18 NOV-TRCS Meeting 25 NOV-TRCS Meeting 02 DEC-TRCS Meeting-Change of Command 09 DEC-TRCS Meeting 16 DEC-TRCS Annual Holiday Party 27 DEC-03 JAN-Cadet Leadership/NCO School Sean O'Toole, USMC SENIOR MEETING NOTES meeting which was held after Commander's Call. -

The Story of Captain Jack Alcock - First to Fly the Atlantic Non-Stop in 1919, Joseph F Alcock, Aerospace Publishers, 2013, 0989011100, 9780989011105

Tomorrow Has Wings: The Story of Captain Jack Alcock - First to Fly the Atlantic Non-Stop in 1919, Joseph F Alcock, Aerospace Publishers, 2013, 0989011100, 9780989011105, . Other authors have written about the first non-stop flight across the Atlantic, flown by Alcock and Brown, but have not covered the men involved in great detail. "Tomorrow Has Wings" has encapsulated accurately the life, career and other achievements of Captain Jack Alcock, as well as the historic flight across the Atlantic. In so doing, the book brings to life the personalities involved in the development of aviation in Great Britain, such as Tommy Sopwith, Harry Hawker and Freddie Raynham.. DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1eNs8fr Frederick Douglass A Biography, C. James Trotman, 2011, Biography & Autobiography, 158 pages. Profiles the life and accomplishments of the African American who escaped from slavery to become a prominent abolitionist leader.. The great Atlantic air race , Percy Rowe, 1977, Technology & Engineering, 224 pages. Flying the Atlantic in Sixteen Hours, with a Discussion of Aircraft in Commerce and Transportation , Arthur Whitten Brown, 2008, History, 208 pages. Many of the earliest books, particularly those dating back to the 1900s and before, are now extremely scarce and increasingly expensive. We are republishing these classic works .... Yesterday We Were in America Alcock and Brown - First to Fly the Atlantic Non-Stop, Brendan Lynch, 2009, Transportation, 256 pages. On 14 June 1919 John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown took off from Newfoundland in their open-cockpit Vickers Vimy converted bomber to attempt a non-stop crossing of the .... The Story of Alcock and Brown , Carolyn Sloan, Simon Smith, 1998, Juvenile Nonfiction, 32 pages. -

Alcock & Brown

ALCOCK & BROWN ‘Knights of the Air’ ALCOCK & BROWN Centenary 2019 1 Knights of the Air ALCOCK & BROWN ALCOCK & BROWN Foreword Welcome Crayford has a long and interesting history. It is mentioned in the Domesday On starting these few words, I returned Now that we have arrived at 2019, Book of 1086, has experienced settlements since Roman times or before, and to my very first email on the subject, I hope we have done justice to this it has been important in our nation’s story. Modern Crayford really dates from addressed at that time to Bexley’s centenary celebration of a marvellous the 19th century, when the quiet village at the crossing of the River Cray with Cabinet Member for Arts and Leisure, achievement by two airmen, their its Norman church of St. Paulinus, was transformed into an industrial town. and I was amazed it was dated 2009, wonderful Vimy plane and of course some ten years ago. I asked for his the Vickers workforce of Crayford who The coming of the railway and the establishment of the Vickers factory backing and it was wonderful that made their flight possible. necessitated more homes, shops and facilities in the town. Vickers, mainly he agreed with me that this was too known for its armaments, was also important in the development of cars I must thank from the bottom of my special an event for Crayford not to and aircraft here in Crayford. It was a pioneering company with a large, heart all those involved with this project celebrate it. We even joked that at local workforce. -

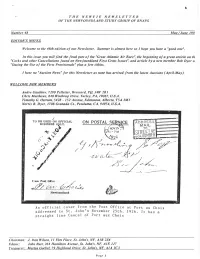

T. of 771E NEWFOUNDLAND STUDY GROUP of BNAPS EDITOR's

t. THE NEWFIE NEWSLETTER OF 771E NEWFOUNDLAND STUDY GROUP OF BNAPS Number 48 May/June 199 EDITOR'S NOTES Welcome to the 48th edition of our Newsletter . Summer is almost here so I hope you have a "good one. In this issue you will find the final part of the "Great Atlantic Air Race ", the beginning of a great article on th "Corks and other Cancellations found on Newfoundland First Cents Issues and article by a new member Bob Dyer o, "Dating the Use of the First Provisionals " plus a few titbits. I have no "Auction News" for this Newsletter as none has arrived from the latest Auctions (April-May). WELCOAIE NEW MEMBERS Andre Gauthier, 7290 Pelletier, Brossard, PQ, J41V 2R I Chris Matthews, 840 Winthrop Drive, Yarley, PA, 19067, U.S.A. Timothy G. Ostrum, 5428 - 152 Avenue, Edmonton, Alberta, T5A 2M1 Norris R. Dyer, 1708 Granada Cl., Petaluma , CA, 94954, U.S.A. An official cover from the Post Office at Port au Choix addressed to St. John's November 25th. 1926. It has a straight line Cancel of Port aux Choix Chairman: J. Don Wilson, I I Elm Place, St. John's, NF, A I B 2S4 Editor: John Bull, 264 Hamilton Avenue, St. John's, NF, AIE 1J7 Treasurer: Marlin Goebel, 79 Ilighland Drive, St. John's. NF. AIA 3C3 pant I Number 48 N E W S L E T T E R Afu Jiute 9. DATING THE USE OF THE FIRST PROVISIONALS In October of 1897, Newfoundland postal officials found themselves without 1(P stamps, due to speculation on the 1(V Cabot issue.