Dynamic Program Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executable Code Is Not the Proper Subject of Copyright Law a Retrospective Criticism of Technical and Legal Naivete in the Apple V

Executable Code is Not the Proper Subject of Copyright Law A retrospective criticism of technical and legal naivete in the Apple V. Franklin case Matthew M. Swann, Clark S. Turner, Ph.D., Department of Computer Science Cal Poly State University November 18, 2004 Abstract: Copyright was created by government for a purpose. Its purpose was to be an incentive to produce and disseminate new and useful knowledge to society. Source code is written to express its underlying ideas and is clearly included as a copyrightable artifact. However, since Apple v. Franklin, copyright has been extended to protect an opaque software executable that does not express its underlying ideas. Common commercial practice involves keeping the source code secret, hiding any innovative ideas expressed there, while copyrighting the executable, where the underlying ideas are not exposed. By examining copyright’s historical heritage we can determine whether software copyright for an opaque artifact upholds the bargain between authors and society as intended by our Founding Fathers. This paper first describes the origins of copyright, the nature of software, and the unique problems involved. It then determines whether current copyright protection for the opaque executable realizes the economic model underpinning copyright law. Having found the current legal interpretation insufficient to protect software without compromising its principles, we suggest new legislation which would respect the philosophy on which copyright in this nation was founded. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION................................................................................................. 1 THE ORIGIN OF COPYRIGHT ........................................................................... 1 The Idea is Born 1 A New Beginning 2 The Social Bargain 3 Copyright and the Constitution 4 THE BASICS OF SOFTWARE .......................................................................... -

Studying the Real World Today's Topics

Studying the real world Today's topics Free and open source software (FOSS) What is it, who uses it, history Making the most of other people's software Learning from, using, and contributing Learning about your own system Using tools to understand software without source Free and open source software Access to source code Free = freedom to use, modify, copy Some potential benefits Can build for different platforms and needs Development driven by community Different perspectives and ideas More people looking at the code for bugs/security issues Structure Volunteers, sponsored by companies Generally anyone can propose ideas and submit code Different structures in charge of what features/code gets in Free and open source software Tons of FOSS out there Nearly everything on myth Desktop applications (Firefox, Chromium, LibreOffice) Programming tools (compilers, libraries, IDEs) Servers (Apache web server, MySQL) Many companies contribute to FOSS Android core Apple Darwin Microsoft .NET A brief history of FOSS 1960s: Software distributed with hardware Source included, users could fix bugs 1970s: Start of software licensing 1974: Software is copyrightable 1975: First license for UNIX sold 1980s: Popularity of closed-source software Software valued independent of hardware Richard Stallman Started the free software movement (1983) The GNU project GNU = GNU's Not Unix An operating system with unix-like interface GNU General Public License Free software: users have access to source, can modify and redistribute Must share modifications under same -

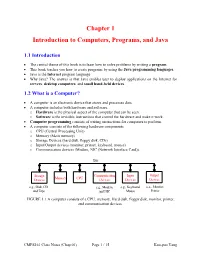

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java 1.1 Introduction • The central theme of this book is to learn how to solve problems by writing a program . • This book teaches you how to create programs by using the Java programming languages . • Java is the Internet program language • Why Java? The answer is that Java enables user to deploy applications on the Internet for servers , desktop computers , and small hand-held devices . 1.2 What is a Computer? • A computer is an electronic device that stores and processes data. • A computer includes both hardware and software. o Hardware is the physical aspect of the computer that can be seen. o Software is the invisible instructions that control the hardware and make it work. • Computer programming consists of writing instructions for computers to perform. • A computer consists of the following hardware components o CPU (Central Processing Unit) o Memory (Main memory) o Storage Devices (hard disk, floppy disk, CDs) o Input/Output devices (monitor, printer, keyboard, mouse) o Communication devices (Modem, NIC (Network Interface Card)). Bus Storage Communication Input Output Memory CPU Devices Devices Devices Devices e.g., Disk, CD, e.g., Modem, e.g., Keyboard, e.g., Monitor, and Tape and NIC Mouse Printer FIGURE 1.1 A computer consists of a CPU, memory, Hard disk, floppy disk, monitor, printer, and communication devices. CMPS161 Class Notes (Chap 01) Page 1 / 15 Kuo-pao Yang 1.2.1 Central Processing Unit (CPU) • The central processing unit (CPU) is the brain of a computer. • It retrieves instructions from memory and executes them. -

Some Preliminary Implications of WTO Source Code Proposala INTRODUCTION

Some preliminary implications of WTO source code proposala INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 1 HOW THIS IS TRIMS+ ....................................................................................................................................... 3 HOW THIS IS TRIPS+ ......................................................................................................................................... 3 WHY GOVERNMENTS MAY REQUIRE TRANSFER OF SOURCE CODE .................................................................. 4 TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER ........................................................................................................................................... 4 AS A REMEDY FOR ANTICOMPETITIVE CONDUCT ............................................................................................................. 4 TAX LAW ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 IN GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT ................................................................................................................................ 5 WHY GOVERNMENTS MAY REQUIRE ACCESS TO SOURCE CODE ...................................................................... 5 COMPETITION LAW ................................................................................................................................................. -

Three Architectural Models for Compiler-Controlled Speculative

Three Architectural Mo dels for Compiler-Controlled Sp eculative Execution Pohua P. Chang Nancy J. Warter Scott A. Mahlke Wil liam Y. Chen Wen-mei W. Hwu Abstract To e ectively exploit instruction level parallelism, the compiler must move instructions across branches. When an instruction is moved ab ove a branch that it is control dep endent on, it is considered to b e sp eculatively executed since it is executed b efore it is known whether or not its result is needed. There are p otential hazards when sp eculatively executing instructions. If these hazards can b e eliminated, the compiler can more aggressively schedule the co de. The hazards of sp eculative execution are outlined in this pap er. Three architectural mo dels: re- stricted, general and b o osting, whichhave increasing amounts of supp ort for removing these hazards are discussed. The p erformance gained by each level of additional hardware supp ort is analyzed using the IMPACT C compiler which p erforms sup erblo ckscheduling for sup erscalar and sup erpip elined pro cessors. Index terms - Conditional branches, exception handling, sp eculative execution, static co de scheduling, sup erblo ck, sup erpip elining, sup erscalar. The authors are with the Center for Reliable and High-Performance Computing, University of Illinois, Urbana- Champaign, Illinoi s, 61801. 1 1 Intro duction For non-numeric programs, there is insucient instruction level parallelism available within a basic blo ck to exploit sup erscalar and sup erpip eli ned pro cessors [1][2][3]. Toschedule instructions b eyond the basic blo ck b oundary, instructions havetobemoved across conditional branches. -

Advanced Systems Security: Symbolic Execution

Systems and Internet Infrastructure Security Network and Security Research Center Department of Computer Science and Engineering Pennsylvania State University, University Park PA Advanced Systems Security:! Symbolic Execution Trent Jaeger Systems and Internet Infrastructure Security (SIIS) Lab Computer Science and Engineering Department Pennsylvania State University Systems and Internet Infrastructure Security (SIIS) Laboratory Page 1 Problem • Programs have flaws ‣ Can we find (and fix) them before adversaries can reach and exploit them? • Then, they become “vulnerabilities” Systems and Internet Infrastructure Security (SIIS) Laboratory Page 2 Vulnerabilities • A program vulnerability consists of three elements: ‣ A flaw ‣ Accessible to an adversary ‣ Adversary has the capability to exploit the flaw • Which one should we focus on to find and fix vulnerabilities? ‣ Different methods are used for each Systems and Internet Infrastructure Security (SIIS) Laboratory Page 3 Is It a Flaw? • Problem: Are these flaws? ‣ Failing to check the bounds on a buffer write? ‣ printf(char *n); ‣ strcpy(char *ptr, char *user_data); ‣ gets(char *ptr) • From man page: “Never use gets().” ‣ sprintf(char *s, const char *template, ...) • From gnu.org: “Warning: The sprintf function can be dangerous because it can potentially output more characters than can fit in the allocation size of the string s.” • Should you fix all of these? Systems and Internet Infrastructure Security (SIIS) Laboratory Page 4 Is It a Flaw? • Problem: Are these flaws? ‣ open( filename, O_CREAT ); -

Opportunities and Open Problems for Static and Dynamic Program Analysis Mark Harman∗, Peter O’Hearn∗ ∗Facebook London and University College London, UK

1 From Start-ups to Scale-ups: Opportunities and Open Problems for Static and Dynamic Program Analysis Mark Harman∗, Peter O’Hearn∗ ∗Facebook London and University College London, UK Abstract—This paper1 describes some of the challenges and research questions that target the most productive intersection opportunities when deploying static and dynamic analysis at we have yet witnessed: that between exciting, intellectually scale, drawing on the authors’ experience with the Infer and challenging science, and real-world deployment impact. Sapienz Technologies at Facebook, each of which started life as a research-led start-up that was subsequently deployed at scale, Many industrialists have perhaps tended to regard it unlikely impacting billions of people worldwide. that much academic work will prove relevant to their most The paper identifies open problems that have yet to receive pressing industrial concerns. On the other hand, it is not significant attention from the scientific community, yet which uncommon for academic and scientific researchers to believe have potential for profound real world impact, formulating these that most of the problems faced by industrialists are either as research questions that, we believe, are ripe for exploration and that would make excellent topics for research projects. boring, tedious or scientifically uninteresting. This sociological phenomenon has led to a great deal of miscommunication between the academic and industrial sectors. I. INTRODUCTION We hope that we can make a small contribution by focusing on the intersection of challenging and interesting scientific How do we transition research on static and dynamic problems with pressing industrial deployment needs. Our aim analysis techniques from the testing and verification research is to move the debate beyond relatively unhelpful observations communities to industrial practice? Many have asked this we have typically encountered in, for example, conference question, and others related to it. -

A Parallel Program Execution Model Supporting Modular Software Construction

A Parallel Program Execution Model Supporting Modular Software Construction Jack B. Dennis Laboratory for Computer Science Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, MA 02139 U.S.A. [email protected] Abstract as a guide for computer system design—follows from basic requirements for supporting modular software construction. A watershed is near in the architecture of computer sys- The fundamental theme of this paper is: tems. There is overwhelming demand for systems that sup- port a universal format for computer programs and software The architecture of computer systems should components so users may benefit from their use on a wide reflect the requirements of the structure of pro- variety of computing platforms. At present this demand is grams. The programming interface provided being met by commodity microprocessors together with stan- should address software engineering issues, in dard operating system interfaces. However, current systems particular, the ability to practice the modular do not offer a standard API (application program interface) construction of software. for parallel programming, and the popular interfaces for parallel computing violate essential principles of modular The positions taken in this presentation are contrary to or component-based software construction. Moreover, mi- much conventional wisdom, so I have included a ques- croprocessor architecture is reaching the limit of what can tion/answer dialog at appropriate places to highlight points be done usefully within the framework of superscalar and of debate. We start with a discussion of the nature and VLIW processor models. The next step is to put several purpose of a program execution model. Our Parallelism processors (or the equivalent) on a single chip. -

The Art, Science, and Engineering of Fuzzing: a Survey

1 The Art, Science, and Engineering of Fuzzing: A Survey Valentin J.M. Manes,` HyungSeok Han, Choongwoo Han, Sang Kil Cha, Manuel Egele, Edward J. Schwartz, and Maverick Woo Abstract—Among the many software vulnerability discovery techniques available today, fuzzing has remained highly popular due to its conceptual simplicity, its low barrier to deployment, and its vast amount of empirical evidence in discovering real-world software vulnerabilities. At a high level, fuzzing refers to a process of repeatedly running a program with generated inputs that may be syntactically or semantically malformed. While researchers and practitioners alike have invested a large and diverse effort towards improving fuzzing in recent years, this surge of work has also made it difficult to gain a comprehensive and coherent view of fuzzing. To help preserve and bring coherence to the vast literature of fuzzing, this paper presents a unified, general-purpose model of fuzzing together with a taxonomy of the current fuzzing literature. We methodically explore the design decisions at every stage of our model fuzzer by surveying the related literature and innovations in the art, science, and engineering that make modern-day fuzzers effective. Index Terms—software security, automated software testing, fuzzing. ✦ 1 INTRODUCTION Figure 1 on p. 5) and an increasing number of fuzzing Ever since its introduction in the early 1990s [152], fuzzing studies appear at major security conferences (e.g. [225], has remained one of the most widely-deployed techniques [52], [37], [176], [83], [239]). In addition, the blogosphere is to discover software security vulnerabilities. At a high level, filled with many success stories of fuzzing, some of which fuzzing refers to a process of repeatedly running a program also contain what we consider to be gems that warrant a with generated inputs that may be syntactically or seman- permanent place in the literature. -

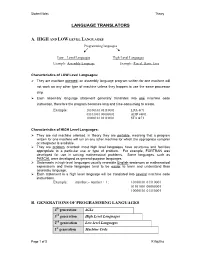

Language Translators

Student Notes Theory LANGUAGE TRANSLATORS A. HIGH AND LOW LEVEL LANGUAGES Programming languages Low – Level Languages High-Level Languages Example: Assembly Language Example: Pascal, Basic, Java Characteristics of LOW Level Languages: They are machine oriented : an assembly language program written for one machine will not work on any other type of machine unless they happen to use the same processor chip. Each assembly language statement generally translates into one machine code instruction, therefore the program becomes long and time-consuming to create. Example: 10100101 01110001 LDA &71 01101001 00000001 ADD #&01 10000101 01110001 STA &71 Characteristics of HIGH Level Languages: They are not machine oriented: in theory they are portable , meaning that a program written for one machine will run on any other machine for which the appropriate compiler or interpreter is available. They are problem oriented: most high level languages have structures and facilities appropriate to a particular use or type of problem. For example, FORTRAN was developed for use in solving mathematical problems. Some languages, such as PASCAL were developed as general-purpose languages. Statements in high-level languages usually resemble English sentences or mathematical expressions and these languages tend to be easier to learn and understand than assembly language. Each statement in a high level language will be translated into several machine code instructions. Example: number:= number + 1; 10100101 01110001 01101001 00000001 10000101 01110001 B. GENERATIONS OF PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES 4th generation 4GLs 3rd generation High Level Languages 2nd generation Low-level Languages 1st generation Machine Code Page 1 of 5 K Aquilina Student Notes Theory 1. MACHINE LANGUAGE – 1ST GENERATION In the early days of computer programming all programs had to be written in machine code. -

Visual Representations of Executing Programs

Visual Representations of Executing Programs Steven P. Reiss Department of Computer Science Brown University Providence, RI 02912-1910 401-863-7641, FAX: 401-863-7657 {spr}@cs.brown.edu Abstract Programmers have always been curious about what their programs are doing while it is exe- cuting, especially when the behavior is not what they are expecting. Since program execution is intricate and involved, visualization has long been used to provide the programmer with appro- priate insights into program execution. This paper looks at the evolution of on-line visual repre- sentations of executing programs, showing how they have moved from concrete representations of relatively small programs to abstract representations of larger systems. Based on this examina- tion, we describe the challenges implicit in future execution visualizations and methodologies that can meet these challenges. 1. Introduction An on-line visual representation of an executing program is a graphical display that provides information about what a program is doing as the program does it. Visualization is used to make the abstract notion of a computer executing a program concrete in the mind of the programmer. The concurrency of the visualization in con- junction with the execution lets the programmer correlate real time events (e.g., inputs, button presses, error messages, or unexpected delays) with the visualization, making the visualization more useful and meaningful. Visual representations of executing programs have several uses. First, they have traditionally been used for program understanding as can be seen from their use in most algorithm animation systems [37,52]. Second, in various forms they have been integrated into debuggers and used for debugging [2,31]. -

Identifying Executable Plans

Identifying executable plans Tania Bedrax-Weiss∗ Jeremy D. Frank Ari K. J´onssony Conor McGann∗ NASA Ames Research Center, MS 269-2 Moffett Field, CA 94035-1000, ftania,frank,jonsson,[email protected] Abstract AI solutions for planning and plan execution often use declarative models to describe the domain of interest. Generating plans for execution imposes a different set The planning system typically uses an abstract, long- of requirements on the planning process than those im- term model and the execution system typically uses a posed by planning alone. In highly unpredictable ex- ecution environments, a fully-grounded plan may be- concrete, short-term model. In most systems that deal come inconsistent frequently when the world fails to with planning and execution, the language used in the behave as expected. Intelligent execution permits mak- declarative model for planning is different than the lan- ing decisions when the most up-to-date information guage used in the execution model. This approach en- is available, ensuring fewer failures. Planning should forces a rigid separation between the planning model acknowledge the capabilities of the execution system, and the execution model. The execution system and the both to ensure robust execution in the face of uncer- planning system have to agree on the semantics of the tainty, which also relieves the planner of the burden plan, and having two separate models requires the sys- of making premature commitments. We present Plan tem designer to replicate the information contained in Identification Functions (PIFs), which formalize what the planning model in the execution model.