[email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Noahidism Or B'nai Noah—Sons of Noah—Refers To, Arguably, a Family

Noahidism or B’nai Noah—sons of Noah—refers to, arguably, a family of watered–down versions of Orthodox Judaism. A majority of Orthodox Jews, and most members of the broad spectrum of Jewish movements overall, do not proselytize or, borrowing Christian terminology, “evangelize” or “witness.” In the U.S., an even larger number of Jews, as with this writer’s own family of orientation or origin, never affiliated with any Jewish movement. Noahidism may have given some groups of Orthodox Jews a method, arguably an excuse, to bypass the custom of nonconversion. Those Orthodox Jews are, in any event, simply breaking with convention, not with a scriptural ordinance. Although Noahidism is based ,MP3], Tạləmūḏ]תַּלְמּוד ,upon the Talmud (Hebrew “instruction”), not the Bible, the text itself does not explicitly call for a Noahidism per se. Numerous commandments supposedly mandated for the sons of Noah or heathen are considered within the context of a rabbinical conversation. Two only partially overlapping enumerations of seven “precepts” are provided. Furthermore, additional precepts, not incorporated into either list, are mentioned. The frequently referenced “seven laws of the sons of Noah” are, therefore, misleading and, indeed, arithmetically incorrect. By my count, precisely a dozen are specified. Although I, honestly, fail to understand why individuals would self–identify with a faith which labels them as “heathen,” that is their business, not mine. The translations will follow a series of quotations pertinent to this monotheistic and ,MP3], tạləmūḏiy]תַּלְמּודִ י ,talmudic (Hebrew “instructive”) new religious movement (NRM). Indeed, the first passage quoted below was excerpted from the translated source text for Noahidism: Our Rabbis taught: [Any man that curseth his God, shall bear his sin. -

Internalizing Borderlands: the Performance of Borderlands Identity

Internalizing Borderlands: the Performance of Borderlands Identity by Megan De Roover A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Megan De Roover, December, 2012 ABSTRACT Internalizing Borderlands: the Performance of Borderlands Identity Megan De Roover Advisor: University of Guelph, 2012 Professor Martha Nandorfy In order to establish a working understanding of borders, the critical conversation must be conscious of how the border is being used politically, theoretically, and socially. This thesis focuses on the border as forcibly ensuring the performance of identity as individuals, within the context of borderlands, become embodiments of the border, and their performance of identity is created by the influence of external borders that become internalized. The internalized border can be read both as infection, a problematic divide needing to be removed, as well as an opportunity for bridging, crossing that divide. I bring together Charles Bowden (Blue Desert), Monique Mojica (Princess Pocahontas and the Blue Spots), Leslie Marmon Silko (Ceremony, Almanac of the Dead), and Guillermo Verdecchia (Fronteras Americanas) in order to develop a comprehensive analysis of the border and border identity development. In these texts, individuals are forced to negotiate their sense of self according to pre-existing cultural and social expectations on either side of the border, performing identity according to how they want to be socially perceived. The result can often be read as a fragmentation of identity, a discrepancy between how the individual feels and how they are read. I examine how identity performance occurs within the context of the border, brought on by violence and exemplified through the division between the spirit world and the material world, the manipulation of costuming and uniforms, and the body. -

Female Cartographers: Historical Obstacles and Successes

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects Honors College at WKU 2020 Female Cartographers: Historical Obstacles and Successes Eva Llamas-Owens Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the History Commons, Other Geography Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Llamas-Owens, Eva, "Female Cartographers: Historical Obstacles and Successes" (2020). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 877. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/877 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FEMALE CARTOGRAPHERS: HISTORICAL OBSTACLES AND SUCCESSES A Capstone Experience/Thesis Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Science with Mahurin Honors College Graduate Distinction at Western Kentucky University By Eva Llamas-Owens May 2020 ***** CE/T Committee: Prof. Amy Nemon, Chair Dr. Leslie North Prof. Susann Davis Copyright by Eva R. Llamas-Owens 2020 ABSTRACT For much of history, women have lived in male-dominated societies, which has limited their participation in society. The field of cartography has been largely populated by men, but despite cultural obstacles, there are records of women significantly contributing over the past 1,000 years. Historically, women have faced coverture, stereotypes, lack of opportunities, and lack of recognition for their accomplishments. Their involvement in cartography is often a result of education or valuable experiences, availability of resources, a supportive community or mentor, hard work, and luck regardless of when and where they lived. -

Guillermo Verdecchia Theatre Artist / Teacher 46 Carus Ave

Guillermo Verdecchia Theatre Artist / Teacher 46 Carus Ave. Toronto, ON M6G 2A4 (416) 516 9574 [email protected] [email protected] Education M.A University of Guelph, School of English and Theatre Studies, August 2005 Thesis: Staging Memory, Constructing Canadian Latinidad (Supervisor: Ric Knowles) Recipient Governor-General's Gold Medal for Academic Achievement Ryerson Theatre School Acting Program 1980-82 Languages English, Spanish, French Theatre (selected) DIRECTING Two Birds, One Stone 2017 by Rimah Jabr and Natasha Greenblatt. Theatre Centre, Riser Project, Toronto The Thirst of Hearts 2015 by Thomas McKechnie Soulpepper, Theatre, Toronto The Art of Building a Bunker 2013 -15 by Adam Lazarus and Guillermo Verdecchia Summerworks Theatre Festival, Factory Theatre, Revolver Fest (Vancouver) Once Five Years Pass by Federico Garcia Lorca. National Theatre School. Montreal 2012 Ali and Ali: The Deportation Hearings 2010 by Marcus Youssef, Guillermo Verdecchia, and Camyar Chai Vancouver East Cultural Centre, Factory Theatre Toronto Guillermo Verdecchia 2 A Taste of Empire 2010 by Jovanni Sy, Cahoots Theatre Rice Boy 2009 by Sunil Kuruvilla, Stratford Festival, Stratford. The Five Vengeances 2006 by Jovanni Sy, Humber College, Toronto. The Caucasian Chalk Circle 2006 by Bertolt Brecht, Ryerson Theatre School, Toronto. Romeo and Juliet 2004 by William Shakespeare, Lorraine Kimsa Theatre for Young People, Toronto. The Adventures of Ali & Ali and the aXes of Evil 2003-07 by Youssef, Verdecchia, and Chai. Vancouver, Toronto, Montreal, Edmonton, Victoria, Seattle. Cahoots Theatre Projects 1999 – 2004 ARTISTIC DIRECTOR. Responsible for artistic planning and activities for company dedicated to development and production of new plays representative of Canada's cultural diversity. -

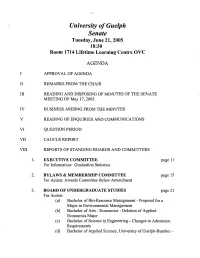

Senate Tuesday, June 21,2005 18:30 Room 1714 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC

University of Guelph Senate Tuesday, June 21,2005 18:30 Room 1714 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC AGENDA APPROVAL OF AGENDA REMARKS FROM THE CHAIR READING AND DISPOSING OF MINUTES OF THE SENATE MEETING OF May 17,2005. IV BUSINESS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES v READING OF ENQUIRIES AND COMMUNICATIONS VI QUESTION PERIOD VII CAUCUS REPORT VIII REPORTS OF STANDING BOARDS AND COMMITTEES 1. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE page 11 For Information: Graduation Statistics BYLAWS & MEMBERSHIP COMMITTEE page 15 For Action: Awards Committee Bylaw Amendment BOARD OF UNDERGRADUATE STUDIES page 21 For Action: (a) Bachelor of Bio-Resource Management - Proposal for a Major in Environmental Management (b) Bachelor of Arts - Economics - Deletion of Applied Economics Major (c) Bachelor of Science in Engineering - Changes to Admission Requirements (d) Bachelor of Applied Science, University of Guelph-Humber - Changes to Admission Requirements (e) Academic Schedule of Dates, 2006-2007 For Information: (0 Course, Additions, Deletions and Changes (g) Editorial Calendar Amendments (i) Grade Reassessment (ii) Readmission - Credit for Courses Taken During Rustication 4. BOARD OF GRADUATE STUDIES page 9 1 For Action: (a) Proposal for a Master of Fine Art in Creative Writing (b) Proposal for a Master of Arts in French Studies For Information: (c) Graduate Faculty Appointments (d) Course Additions, Deletions and Changes 5. COMMITTEE ON AWARDS page 177 For Information: (a) Awards Approved June 2004 - May 2005 (b) Winegard, Forster and Governor General Medal Winners 6. COMMITTEE ON UNIVERSITY PLANNING page 181 For Action: Change of Name for Department of Human Biology and Nutritional Science IX COU RE,PORT X OTHER BUSINESS XI ADJOURNMENT Please note: The Senate Executive will meet at 18:15 in Room 1713 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC just prior to Senate 1r;ne Birrell, Secretary of Senate University of Guelph Senate Tuesday, June 21": 2005 REPORT FROM THE SENATE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Chair: Al Sullivan <[email protected]~ For Information: Graduation Statistics - June 2005 Membership: A. -

The Black Drum Deaf Culture Centre Adam Pottle

THE BLACK DRUM DEAF CULTURE CENTRE ADAM POTTLE ApproximatE Running time: 1 HouR 30 minutEs INcLudes interviews before the performancE and During intermissIoN. A NOTE FROM JOANNE CRIPPS A NOTE FROM MIRA ZUCKERMANN With our focus on oppression, we forget First of all, I would like to thank the DEAF to celebrate Deaf Life. We celebrate Deaf CULTURE CENTRE for bringing me on as Life through sign language, culture and Director of The Black Drum, thereby giving arts. The Black Drum is a full exploration me the opportunity to work with a new and and celebration of our Deaf Canadian exciting international project. The project experience through our unique artistic is a completely new way of approaching practices finally brought together into one musical theatre, and it made me wonder exceptional large scale signed musical. - what do Deaf people define as music? All Almost never do we see Deaf productions Deaf people have music within them, but it that are Deaf led for a fully Deaf authentic is not based on sound. It is based on sight, innovative artistic experience in Canada. and more importantly, sign language. As We can celebrate sign language and Deaf we say - “my hands are my language, my generated arts by Deaf performers for all eyes are my ears”. I gladly accepted the audiences to enjoy together. We hope you invitation to come to Toronto, embarking have a fascinating adventure that you will on an exciting and challenging project that not easily forget and that sets the stage for I hope you all enjoy! more Deaf-led productions. -

FRIENDS and the MUNICIPAL ELECTION - YOUR Involvement Counts

September/October 2014 Volume 6, Issue 2 Mr. Dewey and Friends Newsletter of the Friends of the Guelph Public Library FRIENDS and the MUNICIPAL ELECTION - YOUR Involvement Counts The municipal election will take place on Monday, October 27, 2014. The deadline for declaring intent to stand for election has now passed, and the names of all candidates for Mayor and Council are a matter of public record. As a registered charity, the Friends of the Guelph Public Library cannot support any particular candidate for any office. The role of the group and its members and supporters is always to support and advocate for the Library in every possible way, not only concerning library buildings, but also concerning financial support to maintain our excellent information collection, excellent staff and excellent services. In the context of an election the role of the Friends is to work tirelessly to ensure that voters have full and accurate information about the Library when they examine candidates’ platforms and make their voting choices. It is important that voters select candidates with vision and a broad understanding of the ram- ifications of their platforms. Your role as a supporter of the Library is to inform yourself and be prepared to question candidates and supply accurate information when you encounter misin- formation or uninformed voters between now and election day. Go to all-candidates meetings and ask questions about the Library’s future. For more about library-related issues, there is a wealth of information at Kitty Pope’s blog on the Library website: http://kittysonapositivenote.wordpress.com/. -

Dominican Republic Country Reader Table of Contents

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS William Belton 1940-1942 3rd Secretary and Vice Consul, Ciudad Trujillo William Tapley Bennett 1941-1944 Ci il Attach#, Ciudad Trujillo $ames McCargar 1943-1944 Economic/Consular Officer, Ciudad Trujillo G. -ar ey Summ 194.-1949 Administrati e/Political Officer, Ciudad Trujillo William Belton 1949-1902 1eputy Chief of Mission, Ciudad Trujillo Wendell W. Wood2ury 1902-1904 Economic Officer, Ciudad Trujillo $oseph S. 3arland 1907-1950 Am2assador, 1ominican Repu2lic -enry 1ear2orn 1909-1951 1eputy Chief of Mission, Ciudad Trujillo Gerald $. Monroe 1951-1952 Visa Officer, Santo 1omingo -arry W. Shlaudeman 1952-1953 En oy, 1ominican Repu2lic 7e8is M. White 1952-1954 Economic Officer, Santo 1omingo Ser2an Vallimarescu 1952-1954 Pu2lic Affairs Officer, Santo 1omingo Ale9ander 3. Watson 1952-1950 Consular/Political Officer, Santo 1omingo $ohn -ugh Crimmins 1953-1955 1irector, 1ominican Repu2lic Affairs, Washington, 1C 1orothy $ester 1954-1950 Economic Officer, Santo 1omingo William Tapley Bennett 1954-1955 Am2assador, 1ominican Repu2lic $ohn A. Bushnell 1954-1957 Economic : AI1 Officer, Santo 1omingo Cyrus R. Vance 1950 En oy, 1ominican Repu2lic Edmund Murphy 1950 3oreign Information Officer, USIS, Washington, 1C Richard -. Melton 1950-1957 Consular Officer, Santo 1omingo Richard C. Barkley 1950-1957 Vice Consul, Santiago de los Ca2alleros Ro2ert E. White 1950-195. Chief Political Section, Santo 1omingo 7a8rence E. -arrison 1950-195. 1eputy 1irector, USAI1, San Santo 1omingo 1a id E. Simco9 1955-1957 Political Officer, Santo 1omingo $ohn -ugh Crimmins 1955-1959 Am2assador, 1ominican Repu2lic $ohn A. 3erch 1957-1959 Principal Officer, Santiago de los Ca2alleros 7o8ell 3leischer 195.-1971 Political Officer, Santo 1omingo 7a8rence P. -

Platform 008 ESSAYS the North of the South and the West of the East

Platform 008 ESSAYS The North of the South and the West of the East A Provocation to the Question Walter D. Mignolo I How to effectively map the historical and contemporary relationships that exist between North Africa, the Middle East and the 'Global South' is a question that cannot, in my view, be answered without references to the accumulation of cartographic meanings that have created the image of the planet since the sixteenth century. Cartography and international law were two powerful tools with which western civilization built its own image by creating, transforming and managing the image of the world. German legal philosopher, Carl Schmitt, labelled this 500-year history 'linear global thinking'.[1] Linear global thinking is the story of how Europe mapped the world for its own benefit and left a fiction that became an ontology: a division of the world into 'East' and 'West', 'South' and 'North', or 'First', 'Second', and 'Third'.[2] The overall assumption of my meditation is the following: the 'East/West' division was an invention of western Christianity in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth http://www.ibraaz.org/essays/108 October 2014 centuries – an invention that lasted until World War II. The division was used to legitimize the centrality of Europe and its civilizing mission. From World War II onwards, there was a shift to a 'North/South' division, but this time the division was needed to legitimize a mission of development and modernization. The first part of this history was led by Europe, the second by the United States. Now, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, the so-called rise – and return – of the 'East' is drastically altering 500 years' worth of global divisions produced by the western world to advance its imperial designs. -

Part 3 Assyria and Judah Through the Eyes of Isaiah

OLD TESTAMENT SURVEY Lesson 46 – Part 3 Assyria and Judah Through the Eyes of Isaiah When we were in Madaba Jordan, we had a chance to spend time in the Church of Saint George. This Greek Orthodox church has the remains of a mosaic map in the floor of the apse. The map was created in the mid-500’s. The map is huge, 52 feet by 16 feet. Originally it was almost 70 by 23 feet! Over two million tiles were used to make the mosaic map. (See the copy of the map on the following page). The map is not set in the floor with North at the top, like we would expect a map that we see. Instead the map is set so that east on the map is truly set to the east, west to the west, etc. If you were to stand on the map at Madaba, and then point at the map to Bethlehem, you would truly be pointing in the direction of Bethlehem. While the map is oriented around Madaba, Madaba is not in the center of the map. Jerusalem is the map’s center. Jerusalem is also the most detailed portion of the map. It is as if the entire world portrayed in the map revolves or centers on Jerusalem. There are a number of famous maps that set Jerusalem in the center of the world, especially from medieval times. The most famous of these maps are called “T and O” maps, because they divide the world into three continental masses (with a “T”) surrounded by the oceans, which appear as an “O.” This T and O map is from a 12th This famous woodcut map with Jerusalem in century book, Etymologies by Isidore, the center dates from 1581. -

UNIVERSIDAD TECNOLÓGICA NACIONAL Facultad Regional

UNIVERSIDAD TECNOLÓGICA NACIONAL Facultad Regional Concepción del Uruguay Licenciatura en Lengua Inglesa MULTIPLE BORDER IDENTITIES AND CODE-SWITCHING. THE CASE OF FRONTERAS AMERICANAS/ AMERICAN BORDERS BY GUILLERMO VERDECCHIA Tesis presentada por Marcela Paula GHIGLIONE como requisito parcial para la obtención del grado académico de Licenciada en Lengua Inglesa Directora de Tesis: Dra. María Laura SPOTURNO 2016 Concepción del Uruguay, Entre Ríos, Argentina For my parents, Adriana y Jorge, with all respect For my love, Miguel, con todo mi corazón. 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to express my profound gratitude to María Laura Spoturno, my supervisor, for her stimulating discussion and questioning of many of the issues presented in this thesis. Without those invaluable suggestions and continuous encouragement this study could not have been completed. I would also like to acknowledge the coordinator of the career “Licenciatura en Lengua Inglesa”, Paula Aguilar, for her enthusiasm and constant guiding. My third debt of gratitude is to the staff of teachers who shared with us their invaluable insights, enriching comments and materials. Undoubtedly, they have left their mark on both my professional and personal development. Many people have also provided helpful input on this paper, at various stages. For their thoughtful and detailed suggestions through emails, I would particularly like to thank: Carol Myers-Scotton, Guillermo Verdecchia and Pieter Muysken. I also extend my thanks to Rocio Naef who shared with me her valuable comments on numerous revised drafts of this paper. I would like to express my appreciation to Luz Aranda, Celeste Rojas, Yamil Barrios, Tamara Romero, Luciana Sanzberro, Hebe Bouvet and my cousin, Daniela Koczwara, who provided me with helpful academic and technical advice. -

MANUEL ROCHA Ex Director De Asuntos Interamericanos De La Casa Blanca

MANUEL ROCHA Ex director de Asuntos Interamericanos de la Casa Blanca. Uno de los mayores expertos en temas de Latinoamérica El Embajador Manuel Rocha es Diplomático de carrera con un importante recorrido de servicio en el Cuerpo Diplomático de los EEUU, con el que ha llevado a cabo numerosas misiones tanto en el extranjero como en el Departamento de Estado. Licenciado “Cum Laude” en Yale sobre estudios Latinoamericanos, el Embajador Rocha realizó también un Máster en Administraciones Públicas en Harvard y un Máster en Relaciones Internacionales por la Universidad de Georgetown. En sus inicios como joven diplomático ocupó cargos en las Embajadas de México, Honduras, Italia y República Dominicana. De 1994 a 1995 fue director para Asuntos Interamericanos de la Casa Blanca ante el Consejo de Seguridad Nacional. Fue máximo responsable de la oficina de representación de los intereses de EE.UU en la Habana, Cuba, tras lo que fue Encargado de Negocios de la Embajada en Buenos Aires. Posteriormente ocupó el cargo de Embajador en Bolivia hasta 2002. Recibió en 2000 de manos del Presidente argentino la Orden de San Martín, por su esfuerzo en la mejora de las relaciones entre ambos países, recibió también el Cóndor de los Andes de manos del Presidente de Bolivia en 2002. En 2001 destaca el máximo reconocimiento recibido de parte del Presidente de los EEUU por su labor llevada a cabo en la Política exterior de su país. Antes de crear la firma dedicada al desarrollo de negocios “The Globis Group LLC” junto a su socio Rodrigo Arboleda, Rocha formó parte del Consejo de Administración de la firma de Abogados Steel Hector and Davis durante dos años.