Building Socialism and Communism: Planning and the Process of Transcending Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libertarianism, Culture, and Personal Predispositions

Undergraduate Journal of Psychology 22 Libertarianism, Culture, and Personal Predispositions Ida Hepsø, Scarlet Hernandez, Shir Offsey, & Katherine White Kennesaw State University Abstract The United States has exhibited two potentially connected trends – increasing individualism and increasing interest in libertarian ideology. Previous research on libertarian ideology found higher levels of individualism among libertarians, and cross-cultural research has tied greater individualism to making dispositional attributions and lower altruistic tendencies. Given this, we expected to observe positive correlations between the following variables in the present research: individualism and endorsement of libertarianism, individualism and dispositional attributions, and endorsement of libertarianism and dispositional attributions. We also expected to observe negative correlations between libertarianism and altruism, dispositional attributions and altruism, and individualism and altruism. Survey results from 252 participants confirmed a positive correlation between individualism and libertarianism, a marginally significant positive correlation between libertarianism and dispositional attributions, and a negative correlation between individualism and altruism. These results confirm the connection between libertarianism and individualism observed in previous research and present several intriguing questions for future research on libertarian ideology. Key Words: Libertarianism, individualism, altruism, attributions individualistic, made apparent -

Marxist Economics: How Capitalism Works, and How It Doesn't

MARXIST ECONOMICS: HOW CAPITALISM WORKS, ANO HOW IT DOESN'T 49 Another reason, however, was that he wanted to show how the appear- ance of "equal exchange" of commodities in the market camouflaged ~ , inequality and exploitation. At its most superficial level, capitalism can ' V be described as a system in which production of commodities for the market becomes the dominant form. The problem for most economic analyses is that they don't get beyond th?s level. C~apter Four Commodities, Marx argued, have a dual character, having both "use value" and "exchange value." Like all products of human labor, they have Marxist Economics: use values, that is, they possess some useful quality for the individual or society in question. The commodity could be something that could be directly consumed, like food, or it could be a tool, like a spear or a ham How Capitalism Works, mer. A commodity must be useful to some potential buyer-it must have use value-or it cannot be sold. Yet it also has an exchange value, that is, and How It Doesn't it can exchange for other commodities in particular proportions. Com modities, however, are clearly not exchanged according to their degree of usefulness. On a scale of survival, food is more important than cars, but or most people, economics is a mystery better left unsolved. Econo that's not how their relative prices are set. Nor is weight a measure. I can't mists are viewed alternatively as geniuses or snake oil salesmen. exchange a pound of wheat for a pound of silver. -

Global Wealth Inequality

EC11CH05_Zucman ARjats.cls August 7, 2019 12:27 Annual Review of Economics Global Wealth Inequality Gabriel Zucman1,2 1Department of Economics, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720, USA; email: [email protected] 2National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA Annu. Rev. Econ. 2019. 11:109–38 Keywords First published as a Review in Advance on inequality, wealth, tax havens May 13, 2019 The Annual Review of Economics is online at Abstract economics.annualreviews.org This article reviews the recent literature on the dynamics of global wealth https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics- Annu. Rev. Econ. 2019.11:109-138. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org inequality. I first reconcile available estimates of wealth inequality inthe 080218-025852 United States. Both surveys and tax data show that wealth inequality has in- Access provided by University of California - Berkeley on 08/26/19. For personal use only. Copyright © 2019 by Annual Reviews. creased dramatically since the 1980s, with a top 1% wealth share of approx- All rights reserved imately 40% in 2016 versus 25–30% in the 1980s. Second, I discuss the fast- JEL codes: D31, E21, H26 growing literature on wealth inequality across the world. Evidence points toward a rise in global wealth concentration: For China, Europe, and the United States combined, the top 1% wealth share has increased from 28% in 1980 to 33% today, while the bottom 75% share hovered around 10%. Recent studies, however, may underestimate the level and rise of inequal- ity, as financial globalization makes it increasingly hard to measure wealth at the top. -

The Principles of Economics Textbook

The Principles of Economics Textbook: An Analysis of Its Past, Present & Future by Vitali Bourchtein An honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science Undergraduate College Leonard N. Stern School of Business New York University May 2011 Professor Marti G. Subrahmanyam Professor Simon Bowmaker Faculty Advisor Thesis Advisor Bourchtein 1 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................4 Thank You .......................................................................................................................................4 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................5 Summary ..........................................................................................................................................5 Part I: Literature Review ..................................................................................................................6 David Colander – What Economists Do and What Economists Teach .......................................6 David Colander – The Art of Teaching Economics .....................................................................8 David Colander – What We Taught and What We Did: The Evolution of US Economic Textbooks (1830-1930) ..............................................................................................................10 -

EMMA GOLDMAN, ANARCHISM, and the “AMERICAN DREAM” by Christina Samons

AN AMERICA THAT COULD BE: EMMA GOLDMAN, ANARCHISM, AND THE “AMERICAN DREAM” By Christina Samons The so-called “Gilded Age,” 1865-1901, was a period in American his tory characterized by great progress, but also of great turmoil. The evolving social, political, and economic climate challenged the way of life that had existed in pre-Civil War America as European immigration rose alongside the appearance of the United States’ first big businesses and factories.1 One figure emerges from this era in American history as a forerunner of progressive thought: Emma Goldman. Responding, in part, to the transformations that occurred during the Gilded Age, Goldman gained notoriety as an outspoken advocate of anarchism in speeches throughout the United States and through published essays and pamphlets in anarchist newspapers. Years later, she would synthe size her ideas in collections of essays such as Anarchism and Other Essays, first published in 1917. The purpose of this paper is to contextualize Emma Goldman’s anarchist theory by placing it firmly within the economic, social, and 1 Alan M. Kraut, The Huddled Masses: The Immigrant in American Society, 1880 1921 (Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 2001), 14. 82 Christina Samons political reality of turn-of-the-twentieth-century America while dem onstrating that her theory is based in a critique of the concept of the “American Dream.” To Goldman, American society had drifted away from the ideal of the “American Dream” due to the institutionalization of exploitation within all aspects of social and political life—namely, economics, religion, and law. The first section of this paper will give a brief account of Emma Goldman’s position within American history at the turn of the twentieth century. -

'New Era' Should Have Ended US Debate on Beijing's Ambitions

Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on “A ‘China Model?’ Beijing’s Promotion of Alternative Global Norms and Standards” March 13, 2020 “How Xi Jinping’s ‘New Era’ Should Have Ended U.S. Debate on Beijing’s Ambitions” Daniel Tobin Faculty Member, China Studies, National Intelligence University and Senior Associate (Non-resident), Freeman Chair in China Studies, Center for Strategic and International Studies Senator Talent, Senator Goodwin, Honorable Commissioners, thank you for inviting me to testify on China’s promotion of alternative global norms and standards. I am grateful for the opportunity to submit the following statement for the record. Since I teach at National Intelligence University (NIU) which is part of the Department of Defense (DoD), I need to begin by making clear that all statements of fact and opinion below are wholly my own and do not represent the views of NIU, DoD, any of its components, or of the U.S. government. You have asked me to discuss whether China seeks an alternative global order, what that order would look like and aim to achieve, how Beijing sees its future role as differing from the role the United States enjoys today, and also to address the parts played respectively by the Party’s ideology and by its invocation of “Chinese culture” when talking about its ambitions to lead the reform of global governance.1 I want to approach these questions by dissecting the meaning of the “new era for socialism with Chinese characteristics” Xi Jinping proclaimed at the Communist Party of China’s 19th National Congress (afterwards “19th Party Congress”) in October 2017. -

Computers and Economic Democracy

Rev.econ.inst. vol.1 no.se Bogotá 2008 COMPUTERS AND ECONOMIC DEMOCRACY Computadores y democracia económica Allin Cottrell; Paul Cockshott Ph.D. in Economics, professor of Wake Forest University, Winston Salem, USA, [[email protected]]. Ph.D. in Computer Science, researcher of the Glasgow University, Glasgow, United Kingdom, [[email protected]].. The collapse of previously existing socialism was due to causes embedded in its economic mechanism, which are not inherent in all possible socialisms. The article argues that Marxist economic theory, in conjunction with information technology, provides the basis on which a viable socialist economic program can be advanced, and that the development of computer technology and the Internet makes economic planning possible. In addition, it argues that the socialist movement has never developed a correct constitutional program, and that modern technology opens up opportunities for democracy. Finally, it reviews the Austrian arguments against the possibility of socialist calculation in the light of modern computational capacity and the constraints of the Kyoto Protocol. [Keywords: socialist planning, economic calculation, environmental constraints; JEL: P21, P27, P28] El colapso del socialismo anteriormente existente obedeció a causas integradas en su mecanismo económico, que no son inherentes a todos los socialismos posibles. El artículo muestra que la teoría económica marxista, junto con la informática, proporciona el fundamento para adelantar un programa económico socialista viable y que el desarrollo de la informática y de Internet hace posible la planificación económica. Además, argumenta que el movimiento socialista nunca desarrolló un programa constitucional correcto y que la tecnología moderna abre nuevas oportunidades para la democracia. -

The Birth of Communism

Looking for a New Economic Order Tensions across Europe mounted in the 1830s and 1840s, as republican (anti-royalist) movements resisted the reigning monarchies. The monarchy in France had been restored after Napoleon Bonaparte’s final defeat at Waterloo in 1815, albeit with great divisions and debate throughout the country. Italy, Germany, and Austria were likewise ruled by monarchies, but faced growing protest. In addition to tensions about forms of government and freedoms, workers were becoming more vocal and unified in protesting conditions in factories, mines, and mills. The Birth of Communism Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels are regarded as the founders of Marxist ideology, more colloquially known as communism. Both were concerned about the ill effects of industrialism. Marx was an economist, historian, and philosopher. Engels was a German journalist and philosopher. After a two-year stay in Manchester, England, Engels wrote his first book, The Condition of the Working Class in England, which was published in 1845. It was in Manchester that Marx and Engels met for the first time. Although they did not like each other at first, they ended up forming a life- and world- changing partnership. Marx was the more public figure of the partnership, but Engels did much of the supporting work, including providing financial assistance to Marx and editing multiple volumes of their publications. In 1847, a group of Germans, working in England, formed a secret society and contacted Marx, asking him to join them as they developed a political platform. At Engels’s suggestion, the group was named the Communist League. Marx and Engels began writing the pamphlet The Communist Manifesto, composed between December 1847 and January 1848. -

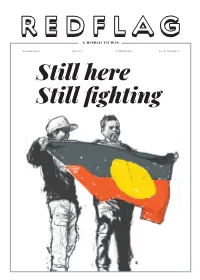

RF177.Pdf (Redflag.Org.Au)

A WORLD TO WIN REDFLAG.ORG.AU ISSUE #177 19 JANUARY 2021 $3 / $5 (SOLIDARITY) Still here Still fi ghting REDFLAG | 19 JANUARY 2021 PUBLICATION OF SOCIALIST ALTERNATIVE REDFLAG.ORG.AU 2 Red Flag Issue # 177 19 January 2021 ISSN: 2202-2228 Published by Red Flag Support the Press Inc. Trades Hall 54 Victoria St Carlton South Vic 3053 [email protected] Christmas Island (03) 9650 3541 Editorial committee Ben Hillier Louise O’Shea Daniel Taylor Corey Oakley rioters James Plested Simone White fail nonetheless. Some are forced to complete rehabil- Visual editor itation programs and told that when they do so their James Plested appeals will be strengthened. They do it. They fail. These are men with families in Australia. They Production are workers who were raising children. They are men Tess Lee Ack n the first week of 2021, detainees at the Christ- who were sending money to impoverished family Allen Myers mas Island Immigration Detention Centre be- members in other countries. Now, with their visas can- Oscar Sterner gan setting it alight. A peaceful protest, which celled, they have no incomes at all. This has rendered Subscriptions started on the afternoon of 5 January, had by partners and children homeless. and publicity evening escalated into a riot over the treatment Before their transportation from immigration fa- Jess Lenehan Iof hundreds of men there by Home Affairs Minister cilities and prisons on the Australian mainland, some Peter Dutton and his Australian Border Force. Four of these men could receive visits from loved ones. Now What is days later, facing down reinforced numbers of masked, they can barely, if at all, get internet access to speak to armed Serco security thugs and Australian Federal them. -

A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 6-11-2009 A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau Jack Turner University of Washington Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Turner, Jack, "A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau" (2009). Literature in English, North America. 70. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/70 A Political Companion to Henr y David Thoreau POLITIcaL COMpaNIONS TO GREat AMERIcaN AUthORS Series Editor: Patrick J. Deneen, Georgetown University The Political Companions to Great American Authors series illuminates the complex political thought of the nation’s most celebrated writers from the founding era to the present. The goals of the series are to demonstrate how American political thought is understood and represented by great Ameri- can writers and to describe how our polity’s understanding of fundamental principles such as democracy, equality, freedom, toleration, and fraternity has been influenced by these canonical authors. The series features a broad spectrum of political theorists, philoso- phers, and literary critics and scholars whose work examines classic authors and seeks to explain their continuing influence on American political, social, intellectual, and cultural life. This series reappraises esteemed American authors and evaluates their writings as lasting works of art that continue to inform and guide the American democratic experiment. -

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

What We Know and Do Not Know About the Natural Rate of Unemployment

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 11, Number 1—Winter 1997—Pages 51–72 What We Know and Do Not Know About the Natural Rate of Unemployment Olivier Blanchard and Lawrence F. Katz lmost 30 years ago, Friedman (1968) and Phelps (1968) developed the concept of the "natural rate of unemployment." In what must be one of Athe longest sentences he ever wrote, Milton Friedman explained: "The natural rate of unemployment is the level which would be ground out by the Wal- rasian system of general equilibrium equations, provided that there is imbedded in them the actual structural characteristics of the labor and commodity markets, in- cluding market imperfections, stochastic variability in demands and supplies, the cost of gathering information about job vacancies and labor availabilities, the costs of mobility, and so on." Over the past three decades a large amount of research has attempted to formalize Friedman's long sentence and to identify, both theo- retically and empirically, the determinants of the natural rate. It is this body of work we assess in this paper. We reach two main conclusions. The first is that there has been considerable theoretical progress over the past 30 years. A framework has emerged, organized around two central ideas. The first is that the labor market is a market with a high level of traffic, with large flows of workers who have either lost their jobs or are looking for better ones. This by itself implies that there must be some "frictional unemployment." The second is that the nature of relations between firms and workers leads to wage setting that often differs substantially from competitive wage setting.