Rosie Campbell Not Getting Away with It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCRATCH COMPETITION Saturday 15 May 2021 the FORMBY HARE

SCRATCH COMPETITION Saturday 15 May 2021 FOR THE THE FORMBY HARE Holder: Greg Holmes Royal Birkdale Golf Club 36 HOLES STROKEPLAY The winner will receive a replica Formby Hare and a voucher. Other winners will be awarded vouchers as set out in the Conditions of Entry. The Lancashire Links Trophy For competitors entering both the Formby Hare and the Southport and Ainsdale Bowl, this will now be recognised as the ‘The Lancashire Links Trophy’ a World Amateur Golf Ranking Event. There will be prizes for the best three aggregate scores over the two competitions. Entrance Fee - £60.00 Cheques payable to Formby Golf Club ENTRIES CLOSE 4.30 pm THURSDAY 15 April 2021 FORMBY HARE CONDITIONS OF ENTRY, REGULATIONS AND PRIZES 1 Entries are invited from male Amateur members of recognised Golf Clubs with a handicap index of 3 or less. 2 Entries on the completed entry form together with the appropriate entrance fee must reach Elaine Black, Formby Golf Club, Golf Road, Formby, Merseyside L37 1LQ by 4.30pm, Thursday 15 April 2021. Enquiries: Monday to Friday 8.30am – 3.30pm, Telephone: 01704 872164 E-mail: [email protected] 3 The Organising Committee will make the draw and the order and times of starting will be posted / emailed to each competitor. All unsuccessful entrants will be advised. The draw will also be available on our website from Wednesday 21st April 2021. In the event of a competitor having to scratch, no entry fee will be returned. 4 The organising committee of the Formby Hare wish to ensure that slow play is avoided wherever possible. -

Zones-Map-June-18.Pdf

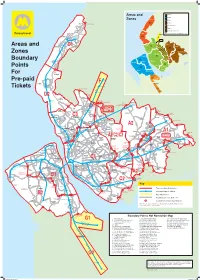

Areas and Zones SOUTHPORT 187 D1 CROSSENS Crossens/Plough Hotel Fylde Rd. Rd. New Preston La. Rd. idge Bankfield Cambr FORMBY CHURCHTOWN ORMSKIRK Rd. La. Roe SOUTHPORT Queens Park D2 MEOLS Lane St. SOUTHPORT COP Old F Sussex Lord Rd. F/C3 Duke St. BLOWICK Rd. MAGHULL Westbourne RAINFORD BIRKDALE La. CROSBY Areas and D1Town BILLINGE BIRKDALE C3 KEW KIRKBY A2 A3/C2/C3 HILLSIDE A1 Road BOOTLE Zones A1/A2 NEWTON-LE-WILLOWS WEST DERBY ST HELENS Liverpool PRESCOT WALLASEY C1 RAINHILL Shore HUYTON Boundary Rd. B1 LIVERPOOL AINSDALE BIRKENHEAD WEST KIRBY C2 GARSTON Points Pinfold HALEWOOD Lane B2 183 SPEKE HESWALL Liverpool Rd./ BROMBOROUGH Woodvale For Camp Gate WOODVALE HOOTON G1 ELLESMERE FRESHFIELD PORT ORMSKIRK Pre-paid Church Rd. Rd. gton F FORMBY CAPENHURST FORMBY Harin Duke St. AUGHTON PARK Tickets Rd. Alt Lydiate/Mairscough Brook G2 177 (RAILPASS ONLY) CHESTER Southport TOWN GREEN Rd. Lydiate/ D2 Robbins Island LYDIATE INCE 178 BLUNDELL Prescot Rd./ HIGHTOWN Park Cunscough La. Wall Rd. Northway Cunscough Lane East Park 170 171 Rainford, RAINFORD Long La./ Wheatsheaf Inn or RAINFORD Broad La. Lane 43 Ince MAGHULL CunscoughLane Ormskirk Road Terminus JUNCTION News La. 173 Lunt . Rd. Rd Ormskirk MAGHULL La. KINGS LUNT NORTH Live MOSS Rd. Poverty Rd Sth. Moss Vale/ LITTLE 176 rpool La. Bridges Prescot . Lane F/C3 La. Stork Inn CROSBY Long La./ Old THORNTON MAGHULL 10 Ince La. Lydiate Rd. Moor Bank RAINFORD La. Lane Cat North Ashton, Edge Hey Rock MELLING La. Newton HALL RD. Lane St. 11 Brocstedes Rd. Lane Red Rd. Moor La. La. 169 Shevingtons Higher C3 Main Garswoo TOWER HILL Church La. -

Heroin Technical Report

The heroin epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s and its effect on crime trends - then and now: Technical Report Nick Morgan July 2014 Contents Summary 3 Chapter 1: Introduction and methodology 6 Chapter 2: An overview of crime trends and explanations of the crime drop 11 Chapter 3: A historical overview of the spread of heroin in England and Wales 49 Chapter 4: The relationship between opiate/crack use and crime 71 Chapter 5: The relationship between opiate/crack use and crime locally, nationally and internationally 80 Chapter 6: Quantifying the impact of changing levels of opiate/crack use on acquisitive crime trends 119 Conclusion 156 References 160 Appendix 1: Table showing peaks in crime types, heroin use and unemployment, by police force area 180 Appendix 2: Trends in acquisitive crime through the crime turning point, by police force area 181 Appendix 3: Addicts Index trends, by police force area 191 Appendix 4: Studies with quantitive data on the criminality of opiate/crack users 196 Appendix 5: Results of the evidence review of OCU exit rates 199 Appendix 6: Detailed description of the short listed studies used in the model 203 Appendix 7: Assumption log for main model 215 Appendix 8: The break in the Addicts Index data 218 Appendix 9: Alternative OCU trend results using excel solver 219 2 Summary A variety of factors have been cited to explain the rise and fall in crime that has occurred in many nations since 1980. But as yet, no definitive explanation has been produced. In the UK context, a rise and fall in illicit drug use has not been especially prominent in this debate, perhaps due to a lack of robust data for the whole period. -

217, 217A (Bootle) Kirkby Bus Station - 227 Huyton Or Halewood These Services Are Provided by Stagecoach and Merseytravel

Valid from 30 August 2020 Bus timetable 217, 217A (Bootle) Kirkby Bus Station - 227 Huyton or Halewood These services are provided by Stagecoach and Merseytravel KIRKBY Bus Station KIRKBY ADMIN Bus Facility KNOWSLEY VILLAGE PAGE MOSS (daytime journeys) LONGVIEW Longview Drive (Eve/Sunday journeys) HUYTON Bus Station NAYLORSFIELD (Eve/Sunday journeys) BELLE VALE Shopping Centre (Eve/Sunday journeys) HUNTS CROSS Macketts Lane (Eve/Sunday journeys) HALEWOOD Shopping Centre (Eve/Sunday journeys) www.merseytravel.gov.uk 217 info page_info test 24/08/2020 14:52 Page 1 What’s changed? Service now runs as normal (as 19 January 2020 timetable). Any comments about this service? If you’ve got any comments or suggestions about the services shown in this timetable, please contact the bus company who runs the service: Stagecoach Merseyside East Lancashire Road, Gillmoss, Liverpool, L11 0BB 0151 330 6200 If it’s a Merseytravel Bus Service we’d like to know what you think of the service, or if you have left something in a bus station, please contact us at Merseytravel: By e-mail [email protected] By phone 0151 330 1000 In writing PO Box 1976, Liverpool, L69 3HN Need some help or more information? For help planning your journey, call 0151 330 1000, open 0800 - 2000, 7 days a week. You can visit one of our Travel Centres across the Merseytravel network to get information about all public transport services. To find out opening times, phone us on 0151 330 1000. Our website contains lots of information about public transport across Merseyside. You can visit our website at www.merseytravel.gov.uk Bus services may run to different timetables during bank and public holidays, so please check your travel plans in advance. -

Best Defence Sectors

Fraud Advisory Panel Ninth Annual Review 2006-2007 Ethical is bestthe defencebehaviour againstfraud It’s all about choices LOW RES PROOF ONLY Ethical behaviour is rooted in individual choices but that’s not the whole story. Government, business and media supply inspirations and incentives that help set the tone of our society. Some of these are making an inadvertent but powerful contribution to the growth of fraud. LOW RES PROOF ONLY Contents The Fraud Advisory Panel is an independent body 2 Chairman’s Overview: with members from both the public and private The Best Defence sectors. Its role is to raise awareness of the immense human, social and economic damage caused by fraud 3 About The Panel and to develop effective remedies. 3 Programme 3 Joining The Panel works to: 3 Corporate Members 4 Trustees • originate proposals to reform the law and public policy, with a particular focus on fraud 6 Public Policy: investigations and prosecutions. “A Once in a Generation Chance” • Advise business and the public on prevention, 6 At least £20 Billion a Year 6 Aspirations and Realities detection and reporting. 7 Six Cheap and Simple Steps • Assist in improving education and training in business and the professions. 8 Ethics and Fraud • Establish a more accurate picture of the extent, 9 The Social Context causes and nature of fraud. 9 Inspirations and Incentives 9 A Zone of Tolerance The Panel has a truly multi-disciplinary perspective. 10 Marginalising Ethical Criteria No other organisation has such a range and depth 10 Getting Away With It of knowledge, both of the problem and of ways to 11 The Business Context combat it. -

Serious Violence in Merseyside

SERIOUS VIOLENCE IN MERSEYSIDE Response Strategy March 2020 Authored by Jill Summers and Mark Wiggins Contents 1. Forward - Police and Crime Commissioner Jane Kennedy and Chief Constable Andy Cooke .......................................... 3 2. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 3. Violence in Merseyside ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Violence in Merseyside ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 4. Mission and Values ............................................................................................................................................................. 7 5. Definitions and the Public Health Approach ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 8 6. Community and stakeholder involvement in our strategic approach ................................................................................. 9 6. Community and stakeholder involvement in our strategic approach ............................................................................... 10 7. Strategic framework .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Huyton Closure GENH2058IAFEB21H

Understanding your branch closure Santander, 57 Derby Road, Huyton L36 9YA This branch will be closing at 4pm on 8 July 2021. We’d like to explain why, and help you understand how you can continue banking with us. Background to our approach Our customers are continuing to change the way they manage their money. As well as using our branches, many more of our customers find it convenient to do their day-to-day banking using Online, Mobile or Telephone Banking. As a result, customers are visiting our branches much less. This change has been happening over a number of years now and has accelerated in recent times. Due to these changes, we have carefully and thoroughly reviewed the way we develop our services for customers and considered many factors, including where each of our branches are located and how they are used. We know our branch network remains very important to our customers. Whilst we have made the difficult decision to close some branches, we have only done so where we know there are other facilities our customers can use and where we have another Santander branch within a few miles. As part of this review, we have assessed each branch individually to consider the potential impact for our customers, colleagues and the alternative options available to bank locally. We hope this leaflet helps to provide more information about our decision to close Huyton branch, the alternative ways to continue to bank with Santander and other local banking services available. Adam Bishop, Head of Branch Interactions Branch assessment Before reaching the decision to close Huyton branch, a full review of the branch was undertaken, including: ¡ The way our Huyton branch customers are choosing ¡ The availability of alternative ways to bank with to bank with us. -

Register of Cooling Towers and Evaporative Condensers

Register of Cooling Towers and Evaporative Condensers Name of Site Address Number of Cooling Towers currently in operation. Aqua Cure Wilson Road, Huyton, Knowsley, One L36 6AN Baker Hughes Kirkby Bank Road, Knowsley Ind. One Park North, L33 7SY B.A.S.F Coatings & Inks Ellis Ashton Street, Huyton One Limited Industrial Estate, L36 6BN Bicc Pyrotenax Limited Hall Lane, Prescot, L34 5JG Three Bicc Rod Rollers Ltd P.O Box 21, Carr Lane, Prescot, Two L34 1PD Bicc Components P.O Box 4, Hall Lane, Prescot, One L34 5UR Bomac Electrical Ltd Randles Road, Knowsley One Business Park, Prescot, L34 9HX Cylinder Cables Limited Stretton Way, Wilson Road, One Huyton, L36 6JF Conix U.K Limited Boulevard Industrial Park, One Halewood, Knowsley, L24 9PL Colloids Kirkby Bank Road, Knowsley, Two Merseyside, L33 7SY Contract Chemicals Ltd Penrhyn Road, Knowsley Four Business Park, Prescot, L34 9HY Corning Cable School Lane, Knowsley, L34 9GS Two Croda Kerr Limited Ashcroft Road, Knowsley One Industrial Park, Kirkby, L33 7TS Crosby Reclaimed Plastic Unit 6, Manor Complex, Kirkby One Bank Road, Kirkby, L33 7SY Dairy Crest Moorgate Road, Kirkby Liverpool Five L33 7XY Decoma Merplas Boulevard Industrial Park, Unit 6, One Renaissance Way Liverpool L24 9PL Dolphin-Fairway (Fairway Randles Road, Knowsley One Packaging Ltd) Industrial Estate L34 9HX Eatwell UK Unit 7 Randles Road, Knowsley One Business Park, Knowsley L34 9HX EP Moulding Limited Yardley Road, Knowsley Industrial Two Park, Kirkby, L33 7SS Essex International Ellis Ashton Street, Huyton, Two Knowsley, -

Name of Site Address Number of Cooling Towers Currently in Operation

Register of Cooling Towers and Evaporative Condensers Name of Site Address Number of Cooling Towers currently in operation. Aqua Cure Wilson Road, Huyton, Knowsley, One L36 6AN Baker Hughes Kirkby Bank Road, Knowsley Ind. Two Park North, L33 7SY Cylinder Cables Limited Stretton Way, Wilson Road, One Huyton, L36 6JF Conix U.K Limited Boulevard Industrial Park, One Halewood, Knowsley, L24 9PL Colloids Kirkby Bank Road, Knowsley, Two Merseyside, L33 7SY Contract Chemicals Ltd Penrhyn Road, Knowsley Six Business Park, Prescot, L34 9HY Croda Kerr Limited Ashcroft Road, Knowsley One Industrial Park, Kirkby, L33 7TS Dairy Crest Moorgate Road, Kirkby Liverpool Four L33 7XY Decoma Merplas Boulevard Industrial Park, Unit 6, One Renaissance Way Liverpool L24 9PL Dolphin-Fairway (Fairway Randles Road, Knowsley One Packaging Ltd) Industrial Estate L34 9HX Eatwell UK Unit 7 Randles Road, Knowsley One Business Park, Knowsley L34 9HX EP Moulding Limited Yardley Road, Knowsley Industrial Two Park, Kirkby, L33 7SS FACI UK Chemicals Ltd Ashcroft Road, Knowsley Two Industrial Park, Merseyside L33 7TW Giddings & Lewis A.G Randles Road, Knowsley Two Industrial Estate, L34 9HX Glen Dimplex Home Stoney Lane, Prescot L35 2XW One Appliances Ltd Goodrich Actuation Stretton Way, Huyton., L36 6JE Four Systems Halewood International The Sovereign Distillery, Wilson Two Limited Road, Huyton Ind Estate, L36 6JX Huyton Heat Treatments Unit 6, Brickfields, Huyton Ind One Estate, Huyton, L36 6HY I.G.M International Ltd Webber Road, Kirkby Sector, One Knowsley Ind Estate, L33 7SW Jaguar Land Rover Limited Halewood Operations, Halewood, Six Liverpool L24 9BJ Merseyside Waste Disposal Stretton Way, Huyton, Merseyside Two Authority L36 6JF New Horizons Global Ltd Penrhyn Road, Knowsley One Business Park, Knowsley L34 9HY Pentagon Fine Chemicals Lower road, Halebank, Widnes, Five Ltd Cheshire WA8 8NS TWR Stetton Way, Huyton, Knowsley, Four L36 6JE Yardley Plastics Ltd Yardley Road, Knowsley Ind Park, Three L33 7SY . -

Financial Statements 2020

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST JULY 2020 Liverpool John Moores University CONTENTS Operating and Financial Review 4 Public Benefit Statement 20 Board of Governors 28 Officers and Advisors of the University 29 Responsibilities of the Board of Governors 29 Corporate Governance 30 Report of the Auditors 40 Statement of Principal Accounting Policies 41 Statement of Consolidated Income and Expenditure 46 Consolidated and University Statement of Changes in Reserves 47 Consolidated and University Balance Sheets 48 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 50 Notes to the Financial Statements 51 3 Liverpool John Moores University Liverpool John Moores University OPERATING AND Student numbers Student applications FINANCIAL REVIEW Scope of the Financial Statements civic and global engagement that builds and deepens our connections - within the city and across the globe - where These are the consolidated statutory accounts of Liverpool John these enrich the lives of our students, our city, and the broader Moores University and its subsidiaries for the year ended 31 July communities of which we are privileged to be part. 2020. We are seeking to realise this vision in a challenging external Our Strategic Plan for 2017-2022 climate. Patterns of demand are changing, competition is increasing, and the funding landscape is becoming more Our Vision constrained. Yet this is also a moment of opportunity, one which Our Vision is to be pioneering modern civic university, delivering will reward imagination, tenacity, relevance, conviction. We believe solutions -

Building Strong Communities

Building Strong Communities Dear Commissioners, Please find enclosed the evidence pack for ‘Building Strong Communities’, which is due to take place on 21 July, 6-9.30pm in Redbridge Central Library. This month’s evidence pack includes: • An overview of the work of the Community Safety Partnership • An overview of crime and ASB in Redbridge • Age Concern Door Step Crime Report • British Crime Survey 2015 • Unit costs of crime used in Integrated Offender Management VfM toolkit • Outreach Advocacy and Case Study • Homerton University Hospital Needs Assessment • Strategy Overview • Overview of Community Cohesion • RECC report for Building Strong Communities • Cumulative submissions received from the Call for Evidence • The results of consultation with relevant community groups and frontline staff. • Outcomes of the Open meetings • Outcomes of the Schools’ Fairness Conference Please do not hesitate to contact me if you have any queries or concerns, and I look forward to meeting with you next Tuesday. Best regards, Jon Owen Executive Policy Officer 1 Fairness Commission: Building Strong Communities Evidence Pack Fairness Commission Evidence Pack Executive Summary Community Safety Overview The evidence pack details the work of the Community Safety Partnership. It also highlights the challenges and the areas where service provision could be strengthened or delivered differently. The evidence pack is divided into a number of interrelated areas of activity or priority. Each area details the work that is undertaken, the challenges and the potential gaps in service provision. The sections are as follows: • Community Service Overview • Crime Overview; • Emerging issues; • Partnership working; • Health and Well Being; and • Areas of particular interest. Section 1: Community Safety Service Overview: 1.1 The Community Safety Service sits within the Environment and Community Services cluster along with other service areas that have interlinked priorities. -

“You'll Never Kill Our Will to Be Free”: Damien Dempsey's “Colony” As A

“You’ll Never Kill Our Will To Be Free”: Damien Dempsey’s “Colony” as a Critique of Historical and Contemporary Colonialism MARTIN J. POWER, AILEEN DILLANE, and EOIN DEVEREUX Abstract: This article, through a musical, lyrical, and contextual analysis of the Irish recording artist Damien Dempsey’s song “Colony,” probes contemporary discourses concerning colonialism and postcolonialism. In presenting Dempsey’s work through this lens, we seek to interrogate how one singer employs protest song as a vehicle for social critique in a nuanced fashion. Our reading reveals different levels of meaning, in part dependent on contextual knowledge. Furthermore, the simple structure belies the complexity of the issues involved in any discussion of postcoloniality in Ireland and beyond, and because of this the song is rendered all the more potent and persuasive. Résumé : Cet article, à travers une analyse de l’enregistrement de la musique, des paroles et du contexte de 44 (2): 29-52. 44 (2): la chanson « Colony » de l’artiste irlandais Damien Dempsey, sonde les discours contemporains au sujet du colonialisme et du postcolonialisme. En présentant les travaux de Dempsey sous ce prisme, nous cherchons à interroger la façon subtile par laquelle le chanteur utilise la chanson engagée comme un véhicule de critique MUSICultures sociale. Notre lecture révèle différents niveaux de sens, dépendant en partie d’une connaissance contextuelle. En outre, la structure simple dément la complexité des questions qui reviennent dans toutes les discussions au sujet du postcolonialisme en Irlande et au-delà, et cette chanson en est, pour cette raison, d’autant plus puissante et convaincante.