?ART-TIME FARMING in CYPRUS a Pilot Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyprus Authentic Route 2

Cyprus Authentic Route 2 Safety Driving in Cyprus Comfort Rural Accommodation Tips Useful Information Only DIGITAL Version A Village Life Larnaka • Livadia • Kellia • Troulloi • Avdellero • Athienou • Petrofani • Lympia • Ancient Idalion • Alampra • Mosfiloti • Kornos • Pyrga • Stavrovouni • Kofinou • Psematismenos • Maroni • Agios Theodoros • Alaminos • Mazotos • Kiti • Hala Sultan Tekke • Larnaka Route 2 Larnaka – Livadia – Kellia – Troulloi – Avdellero – Athienou – Petrofani – Lympia - Ancient Idalion – Alampra – Mosfiloti – Kornos – Pyrga – Stavrovouni – Kofinou – Psematismenos – Maroni – Agios Theodoros – Alaminos – Mazotos – Kiti – Hala Sultan Tekke – Larnaka Margo Agios Arsos Pyrogi Spyridon Agios Tremetousia Tseri Golgoi Sozomenos Melouseia Athienou Potamia Pergamos Petrofani Troulloi Margi Nisou Dali Pera Louroukina Avdellero Pyla Chorio Idalion Kotsiatis Lympia Alampra Agia Voroklini Varvara Agios Kellia Antonios Kochi Mathiatis Sia Aradippou Mosfiloti Agia Livadia Psevdas Anna Ε4 Kalo Chorio Port Kition Kornos Chapelle Delikipos Pyrga Royal LARNAKA Marina Salt LARNAKA BAY Lake Hala Sultan Stavrovouni Klavdia Tekkesi Dromolaxia- Dipotamos Meneou Larnaka Dam Kiti Dam International Alethriko Airport Tersefanou Anglisides Panagia Kivisili Menogeia Kiti Aggeloktisti Perivolia Aplanta Softades Skarinou Kofinou Anafotida Choirokoitia Alaminos Mazotos Cape Kiti Choirokoitia Agios Theodoros Tochni Psematismenos Maroni scale 1:300,000 0 1 2 4 6 8 10 Kilometers Zygi AMMOCHOSTOS Prepared by Lands and Surveys Department, Ministry of Interior, -

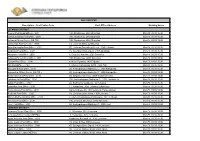

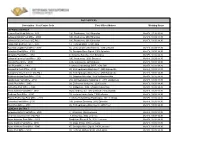

Cost Center Code Post Office Address Working Hours LEFKOSIA

POST OFFICES Description - Cost Center Code Post Office Address Working Hours LEFKOSIA DISTRICT Cyprus Post Head Offices - 1001 100, Prodromou, 2063 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Lefkosia District Post Office - 2000 100, Prodromou, 2063 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Lefkosia Citizen Center (KE.PO.) 100, Prodromou, 2063 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Latsia Mail Sorting Center - 8000 13, Leoforos Kilkis, 2234 Latsia Agioi Omologitai Post Office - 2030 55, Leoforos Dimostheni Severi, 1080 Lefkosia Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Aglantzia Post Office - 2120 16, Georgiou Griva Digeni, 2108 Aglantzia Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Akropolis Post Office - 2050 4, Grigoriou Karekla, 2023 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Lefkosia Parcels Post Office - 2001 100, Prodromou, 2063 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Egkomi Post Office - 2090 4, Neas Egkomis, 2409 Egkomi Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Dali Post Office - 2140 Leoforos Chalkanoros 56DE, 2540 Dali Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Kakopetria Post Office - 2130 20, Archiepiskopou Makariou C', 2800 Kakopetria Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Kakopetria Citizen Center (KE.PO.) 20, Archiepiskopou Makariou C', 2800 Kakopetria Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Kokkinotrimithia Post Office - 2190 59, Grigoriou Afxentiou, 2660 Kokkinotrimithia Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Lakatameia Post Office - 2150 256, Archiepiskopou Makariou C', 2311 Lakatameia Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Latsia Post Office - 2160 20, Eleftheriou Venizelou, 2235 Latsia Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Lykavittos Post Office - 2080 14, Kallipoleos, 1055 Lefkosia (Lykavittos) Mon-Fri, 08.00-15.00 Pallouriotissa Post Office -

Travellers Handbook- Cyprus

www.visitcyprus.com C Y P R U S T R AV E L L E R S H A N D B O O K EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT YOUR STAY IN CYPRUS 1 CYPRUS TOURISM ORGANISATION C Y P R U S T R AV E L L E R S H A N D B O O K The Travellers Handbook is intended to offer the holidaymaker and visitor valuable information about the island, in order to get the most out of their stay in Cyprus. This Handbook is designed to assist to the planning of a trip to Cyprus and to offer information, that will make one’s stay a most pleasant and enjoyable one. MAY YOUR VISIT IN CYPRUS BE A MEMORABLE ONE Cyprus Online: www.visitcyprus.com The Official Website of the Cyprus Tourism Organisation provides comprehensive information on the major attractions of Cyprus, complete with maps, updated calendar of events, detailed hotel guide, downloadable photos and suggested itineraries. You will also find lists of tour operators selling Cyprus, information on conferences and incentives, and a wealth of other useful information. In this leaflet all place names have been converted into Latin characters according to the official System of Transliteration of the Greek alphabet, i.e. LEFKOSIA = NICOSIA LEMESOS = LIMASSOL AMMOCHOSTOS = FAMAGUSTA Notes on pronunciation: ‘ai’: as in English egg ‘oi’, ‘ei’, ‘y’: as in English India 2 ‘ou’: as in English tour TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE General Information on Cyprus . 7-12 Cyprus Tourism Organisation (CTO) . 12 Tourist Information Offices in Cyprus . -

Lefkosia Gastronomy Establishments

Catering and Entertainment Establishments for LEFKOSIA 01/02/2019 Category: RESTAURANT Name Address Telephone Category/ies 1900 OINOU MELATHRON 11-13, PASIKRATOUS STREET, 1011, LEFKOSIA 22667668 & 99622409 RESTAURANT, BAR 48 BISTRO 48Α, ARCH. MAKARIOU C AVENUE, 1065, LEFKOSIA 22664848 RESTAURANT A. PARADISE RESTAURANT ( ASTROMERITIS ) 16, KARYDION STREET, 2722, ASTROMERITIS 22821849, 99527808 RESTAURANT, CAFE ACQUARELLO BEACH RESTAURANT CAFE 38, NIKOLA PAPAGEORGIOU STREET, 2940 KATO PYRGOS 96530034, 99620174 RESTAURANT, CAFE ALFA PIZZA ( KLIROU ) 189, ARCH. MAKARIOU STREET, 2600, KLIROU 22634900 & 99641160 RESTAURANT APERITIVO JETSET LOUNGE 1, TZON KENNETY AVENUE, 1075, LEFKOSIA 22100990, 99537317 RESTAURANT ARGENTINA TZIELLARI - CYPRUS RESTAURANT 72, PALEAS KAKOPETRIAS STREET, 2800, KAKOPETRIA 99967051, 99886001 RESTAURANT ARTE CUCINARIA RESTAURANT 8E, VYZANTIOU STREET, 2064, STROVOLOS 22664799 RESTAURANT ARTISAN'S BURGERBAR 20, STASANDROU STREET, 1060, LEFKOSIA 22759300, 99487445 RESTAURANT ATELIER 3, ARCH. MICHAEL STREET, 1011, LEFKOSIA 22262369 RESTAURANT AVENUE 2, EREXTHIOU STREET, 2413, ENGOMI RESTAURANT B R HUB 22, ΑΤΗΙΝΟΝ AVENUE, 2040, STROVOLOS 70087018, 99288006 RESTAURANT Παρης BABYLON RESTAURANT 6, IASONOS STREET, 1082, LEFKOSIA 22665757, 96221281 RESTAURANT Παύλος BAMBOO CHINESE RESTAURANT 185, LEDRAS & ARSINOIS STREET, 1011, LEFKOSIA 22451111 RESTAURANT ( 1 ) Catering and Entertainment Establishments for LEFKOSIA 01/02/2019 Category: RESTAURANT Name Address Telephone Category/ies BANCO KITCHEN BAR RESTAURANT 15, POUMPOULINAS -

Implementation of Sewerage Systems in Cyprus

MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE , NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT Monitoring of the Implementation Plan in Cyprus Current Status Dr. Dinos A. Poullis Executive Engineer Water Development Department Ministry of Agriculture Natural Resources and Environment Contents Accession Treaty Commitments National Implementation Plan Stakeholders in the Implementation Plan Sewerage Boards Organizational Setup Information and Data Sources for the Preparation of the Implementaton Plan Implementation – current status Work to be Done Difficulties in Implementation Concluding Remarks Accession Treaty Commitments Transitional period negotiated in the accession treaty of Cyprus for the implementation of the UWWTD, Articles 3, 4 and 5(2) ◦ 31.12.2012 Three interim deadlines concerning four agglomerations>15.000pe ◦ 31.12.2008 – 2 agglomerations (Limassol and Paralimni) ◦ 31.12.2009 - 1 agglomeration (Nicosia) ◦ 31.12.2011 - 1 agglomeration (Paphos) National Implementation Plan National Implementation Plan2005 ◦ Submitted to the EC in March 2005 ◦ 6 Urban agglomerations – 545.000pe ◦ 36 Rural agglomerations – 130.000pe National Implementation Plan2008 ◦ Working Groups for Reporting and the EC Guidance Document ◦ Revised NIP-2008 (agglomeration methodology, new technical solutions, government policies and law amendments) ◦ 7 Urban agglomerations – 630.000pe ◦ 50 Rural agglomerations – 230.000pe Article 17 ◦ A revised Implementation Plan is under preparation. Stakeholders in the Implementation Plan Council of Ministers (overall responsibility for the Implementation Plan) Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment Ministry of Interior Ministry of Finance Planning Bureau Sewerage Boards (Established and operate under the “Sewerage Systems Laws 1971 to 2004”) ◦ Urban Sewerage Boards ◦ Rural Sewerage Boards Sewerage Boards Organizational Setup Urban Sewerage Boards ◦ Autonomous organizations (technically and administratively competent) ◦ Carry out their own design, tendering, construction and operation of their sewerage systems. -

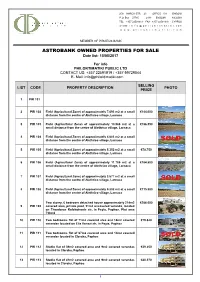

ASTROBANK OWNED PROPERTIES for SALE Date List: 15/05/2017

25th ΜΑRCH STR, 20 · OFFICE 101 · ΕNGOMI P.O. Box 27785 · 2433 ΕNGOMI · NICOSIA ΤEL· +357 22591919 · FAX· +357 22591818 · CYPRUS E- Mail : i n f o @ p h i l o k t i m a t i k i . c o m w w w . p h i l o k t i m a t i k i . c o m MEMBER OF PIRAEUS BANK ASTROBANK OWNED PROPERTIES FOR SALE Date list: 15/05/2017 For info PHILOKTIMATIKI PUBLIC LTD CONTACT US: +357 22591919 / +357 99729044 E- Mail: [email protected] SELLING LIST CODE PROPERTY DESCRIPTION PHOTO PRICE 1 PIR 101 2 PIR 102 Field (Agricultural Zone) of approximately 7.693 m2 at a small €144.000 distance from the centre of Alethrico village, Larnaca 3 PIR 103 Field (Agricultural Zone) of approximately 10.368 m2 at a €196.350 small distance from the centre of Alethrico village, Larnaca 4 PIR 104 Field (Agricultural Zone) of approximately 4.683 m2 at a small distance from the centre of Alethrico village, Larnaca 5 PIR 105 Field (Agricultural Zone) of approximately 5.352 m2 at a small €78.750 distance from the centre of Alethrico village, Larnaca 6 PIR 106 Field (Agricultural Zone) of approximately 11.706 m2 at a €184.800 small distance from the centre of Alethrico village, Larnaca 7 PIR 107 Field (Agricultural Zone) of approximately 3.577 m2 at a small distance from the centre of Alethrico village, Larnaca 8 PIR 108 Field (Agricultural Zone) of approximately 9.202 m2 at a small €115.500 distance from the centre of Alethrico village, Larnaca Two storey, 6 bedroom detached house approximately 214m2 €286.000 9 PIR 109 covered area, private pool, 31m2 uncovered veranda, located on Theodoros Kolokotronis str, in Peyia, Paphos. -

PRESS RELEASE Rapid Antigen Testing for Employees and the General Population – Testing Units 4 April 2021 Aiming at the Contin

GOVERNMENT OF CYPRUS PRESS AND INFORMATION MINISTRY OF INTERIOR OFFICE (P.I.O.) PRESS RELEASE Rapid antigen testing for employees and the general population – Testing units 4 April 2021 Aiming at the continuous surveillance of the community and the workplaces, the free programmes of rapid antigen testing of the general population and employees are in progress. For the smooth and safe operation of businesses that have been activated according to the Decrees, employers in businesses, as well as the Heads of Departments/Services in the public and wider public sector, are obliged to coordinate the rapid testing of the employees, so that the mandatory weekly testing of the personnel, through the rapid antigen test, is ensured as follows: Businesses/services employing up to 3 people, all employees should be tested. Businesses/services employing between 4 to 10 people, at least 4 employees should be tested. Businesses/services employing more than 11 people, at least 5 people or 30% of employees should be tested, whichever is higher in number. Additionally, the self-employed and the domestic employees and/or people caring for elders or disabled persons or people providing assistance to individuals who are unable to take care of themselves are obligated to participate in the program. It is recalled that all teachers and school staff without exception are required to undergo a weekly check with a rapid antigen test. The negative result certificate should be presented during the checks. Thus, employees may proceed to the testing units operating in all Districts, according to the plan designed by the employer/head. -

Scratch Cards Locations for Expand

City NICOSIA NICOSIA NICOSIA ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ LEMESOS NICOSIA ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ΛΕΜΕΣΟΣ LEMESOS AVGOROU FAMAGUSTA LEMESOS ΛΕΜΕΣΟΣ ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ΛΑΡΝΑΚΑ ΠΑΦΟΣ SOTERA FAMAGUSTA ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ΛΑΡΝΑΚΑ NICOSIA NICOSIA LEMESOS ΛΕΜΕΣΟΣ - ΖΑΚΑΚΙ KAIMAKLI NICOSIA ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ - ΕΓΚΩΜΗ ΛΕΜΕΣΟΣ - Κ. ΠΟΛΕΜΙΔΙΑ ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ - Κ. ΔΕΥΤΕΡΑ ΛΑΡΝΑΚΑ FRENAROS FAMAGUSTA ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ - ΓΕΡΙ PAPHOS AG PAVLOS NICOSIA STROVOLOS NICOSIA AGIOI ANARGYROI LARNACA GEROSKIPOU NICOSIA PAPHOS CHLORAKA PAPHOS PAPHOS NICOSIA AVGOROU FAMAGUSTA ARADIPPOU LARNACA KOLOSSI LEMESOS ΑΚΑΚΙ - ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ PAPHOS ΣΤΡΟΒΟΛΟΣ - ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ΜΑΚΕΔΟΝΙΤΙΣΣΑ - ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ΧΟΡΟΚΟΙΤΙΑ -ΛΑΡΝΑΚΑ LARNACA PEGEIA PAPHOS ASTROMERITIS NICOSIA ARADIPPOU LCA STROVOLOS NICOSIA ΓΕΡΟΣΚΗΠΟΥ , ΠΑΦΟΣ KATO PAPHOS LITRODONTAS NICOSIA LARNACA NICOSIA TSERI NICOSIA ΕΓΚΩΜΗ ΣΤΡΟΒΟΛΟΣ ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ PAPHOS NICOSIA ASTROMERITIS NICOSIA ΛΕΜΕΣΟΣ PEGEIA PAPHOS ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ΑΝΘΟΥΠΟΛΗ - ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ORMIDEIA LARNACA ΑΓΛΑΝΤΖΙΑ - ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ERIMI LEMESOS LEMESOS PAPHOS ΑΓΙΟΣ ΔΟΜΕΤΙΟΣ - ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ GEROSKIPOU PAPHOS ΛΕΜΕΣΟΣ ΛΙΜΑΝΙ - ΛΑΡΝΑΚΑΣ AYIA NAPA FAMAGUSTA ΚΑΛΛΙΘΕΑ - ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ΑΓ. ΑΘΑΝΑΣΙΟΣ - ΛΕΜΕΣΟΣ MESOGI PAPHOS ΑΓΙΟΙ ΑΝΑΡΓΥΡΟΙ - ΛΑΡΝΑΚΑ LARNACA ΜΑΚΕΔΟΝΙΤΙΣΣΑ - ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ΤΣΕΡΙ - ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ΚΟΦΙΝΟΥ ΕΜΠΑ ΠΑΦΟΣ ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ΤΡΑΧΩΝΙ -ΛΕΜΕΣΟΣ ΛΑΚΑΤΑΜΕΙΑ - ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ CHLORAKA PAPHOS LATSIA NICOSIA ΤΡΑΧΩΝΙ - ΛΕΜΕΣΟΣ ΑΝΘΟΥΠΟΛΗ - ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ Κ. ΠΟΛΕΜΙΔΙΑ - ΛΕΜΕΣΟΣ ΚΟΚΚΙΝΟΤΡΙΜΙΘΙΑ - ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ARADIPPOU LARNACA NICOSIA PAPHOS AKAKI NICOSIA ΛΥΜΠΙΑ - ΛΕΥΚΩΣΙΑ ΚΡΕΜΜΑΣΤΗΣ ΡΟΔΟΥ 45 PANO DEFTERA NICOSIA PARALIMNI FAMAGUSTA LARNACA SOTERA FAMAGUSTA -

PRESS RELEASE Rapid Antigen Testing Units – 27 June 2021 Aiming

GOVERNMENT OF CYPRUS PRESS AND INFORMATION MINISTRY OF INTERIOR OFFICE (P.I.O.) PRESS RELEASE Rapid antigen testing units – 27 June 2021 Aiming at the continuous surveillance of the community and the workplaces, the free programmes of rapid antigen testing of the general population and employees are in progress. For the smooth and safe operation of businesses that have been activated according to the Decrees, employers in businesses, as well as the Heads of Departments/Services in the public and wider public sector, are obliged to coordinate the rapid testing of the employees, so that the mandatory weekly rapid antigen testing of at least 50% of the personnel working with physical presence, is ensured. Additionally, the self-employed and the domestic employees and/or people caring for elders or disabled persons or people providing assistance to individuals who are unable to take care of themselves are obligated to participate in the program. It is understood that exempt from the above regulation are the employees who have received the 1st dose of a licenced vaccine and three weeks have elapsed from their vaccination. For example, if a company/organization/department of the public/wider public sector employs 20 people with physical presence, of which 12 have received the 1st dose of the vaccine, the obligation for weekly testing concerns the other 8 individuals (4+4). On Sunday, 27 June the testing units will be operating in the following areas: Location of testing units Operating hours Lemesos “Grigoris Afxentiou” Square, Lemesos 8.30 a.m.- (22 units) 7.30 p.m. ‘Andreas Themistocleous’ TEPAK building, Agia Zoni (old 8.30 a.m.- land registry, Athinon street) 7.30 p.m. -

Description - Cost Center Code Post Office Address Working Hours

POST OFFICES Description - Cost Center Code Post Office Address Working Hours LEFKOSIA DISTRICT Cyprus Post Head Offices - 1001 100, Prodromou, 2063 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 07.30-15.00 Lefkosia District Post Office - 2000 100, Prodromou, 2063 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Lefkosia Citizen Center (KE.PO.) 100, Prodromou, 2063 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Latsia Mail Sorting Center - 8000 13, Leoforos Kilkis, 2234 Latsia Agioi Omologitai Post Office - 2030 55, Leoforos Dimostheni Severi, 1080 Lefkosia Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Aglantzia Post Office - 2120 16, Georgiou Griva Digeni, 2108 Aglantzia Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Akropolis Post Office - 2050 4, Grigoriou Karekla, 2023 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Lefkosia Parcels Post Office - 2001 100, Prodromou, 2063 Strovolos Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Egkomi Post Office - 2090 4, Neas Egkomis, 2409 Egkomi Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Dali Post Office - 2140 Leoforos Chalkanoros 56DE, 2540 Dali Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Kakopetria Post Office - 2130 20, Archiepiskopou Makariou C', 2800 Kakopetria Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Kakopetria Citizen Center (KE.PO.) 20, Archiepiskopou Makariou C', 2800 Kakopetria Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Kokkinotrimithia Post Office - 2190 59, Grigoriou Afxentiou, 2660 Kokkinotrimithia Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Lakatameia Post Office - 2150 256, Archiepiskopou Makariou C', 2311 Lakatameia Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Latsia Post Office - 2160 20, Eleftheriou Venizelou, 2235 Latsia Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Lykavittos Post Office - 2080 14, Kallipoleos, 1055 Lefkosia (Lykavittos) Mon-Fri, 08.00-14.30 Pallouriotissa Post Office -

The Ultimate Racing Experience

The Ultimate Racing Experience INTRODUCTION Daytona Raceway was founded in 2006 and has rapidly achieved Life in the recognition in Cyprus as the premier kart racing centre. The Daytona experience combines exciting entertainment and first class fast lane hospitality with cutting edge innovation to ensure guests the ultimate racing www.daytona.co experience. ABOUT US Daytona Raceway, Cyprus’ ultimate karting venue, apart from hospitality and conference facilities also boasts an internationally recognised circuit. The circuit is 1.2 km in length and can be arranged in 3 tracks: • T1- Rental including chicane (blue) Your safety is • T2- National inc. banked and chicane (blue+green) • T3- International inc. banked and chicane (blue+green+yellow) our priority Its more than just racing DAYTONA RACEWAY Tseri — New Nicosia/Limassol Rd P.O.Box 24746 1303 Nicosia Cyprus Phone: 99436683 Fax: 22590214 The karting center is located opposite the industrial area of Dali. This location is approximately 10 minutes from Nicosia visible from E-mail: [email protected] the motorway (EXIT 6 for Tseri) and in close reach from both Larnaca and Limassol. The Ultimate Racing Experience ARRIVE AND DRIVE Practice sessions are ideal for beginners to try kart racing. Subject to availability, Daytona Raceway offers practice sessions on the T1-rental including chicane circuit for drivers aged 7+. Any driver under 18 must be accompanied by a parent or Life in the guardian. fast lane Practice Duration Price € Single Engine Junior / Cadet Kart 15 minutes €12.00 Junior - Age7+ height > 1.35m Cadet - Age 10+ height >1.55m Twin Engine Kart Your safety is 15 minutes €16.00 Adults our priority Age 16+ height >1.55m EXCLUSIVE EVENTS Exclusive events are available, with a number of formats, on the following circuits: Event Race Format Min Max Event T1 T2 T3 It’s more than Drivers Drivers Duration € € € just racing SPRINT 6, 6, 15 Laps 8 12 45 min. -

MOBILITY in NICOSIA Michael Lambrinos & Konstantina Solomou Ministry of Transport, Communications and Works Cyprus EU Europe

MOBILITY IN NICOSIA Michael Lambrinos & Konstantina Solomou Ministry of Transport, Communications and Works Cyprus EU Europe Asia Africa NICOSIA (LEFKOSIA) NICOSIA (LEFKOSIA) A divided city NICOSIA (LEFKOSIA) Population 240.000 (310.000 if occupied part is included) NICOSIA (LEFKOSIA) Area 111 square kilometres NICOSIA (LEFKOSIA) Population density 2200/km2 NICOSIA (LEFKOSIA) Agios Dometios Lefkosia Engomi Aglanja Strovolos 10 municipalities Latsia Yeri Lakatamia Tseri Dali NICOSIA (LEFKOSIA) Radial Road System NICOSIA (LEFKOSIA) Intense development and commercial activity along main arterial roads Weather in Nicosia - Temperature Weather in Nicosia - Rainfall 1960-2006 • Planning exclusively for the car 2006 • Decision to set up a Programme for the Enhancement of Public Transport 2007 • Inclusion of projects of the Programme in the Envelope of EU co-funded projects 2009 – 2010 • Development of the Nicosia Integrated Mobility Master Plan The Nicosia Integrated Mobility Master Plan Achievement of a Development of a polycentric spatial proper network of development public transport Promotion of cycling as Improvement of the a significant mode of service of public transport for short and transport medium distances Creation of a A balanced role for the pedestrian friendly city car Starting Point (2010) 85% Car PT 12% Walk Cycle 1% 2% No. of cars (000) No. of PT Passengers (mln/yr) 600 15 500 12 400 9 300 200 6 100 3 0 0 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2004 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2004 Eurobarometer 2013: Attitudes Towards Urban Mobility Daily Trips