Study Group Report on Approaches to Land Use Administration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disaster Imagination Game at Izunokuni City for Preparedness For

DOI: 10.21276/sjams.2016.4.6.53 Scholars Journal of Applied Medical Sciences (SJAMS) ISSN 2320-6691 (Online) Sch. J. App. Med. Sci., 2016; 4(6D):2129-2132 ISSN 2347-954X (Print) ©Scholars Academic and Scientific Publisher (An International Publisher for Academic and Scientific Resources) www.saspublisher.com Short Communication Disaster Imagination Game at Izunokuni City for preparedness for a huge Nankai Trough earthquake Youichi Yanagawa M.D., Ph.D.1, Ikuto Takeuchi MD.1, Kei Jitsuiki M.D.1, Toshihiko Yoshizawa M.D.1, Kouhei Ishikawa M.D.1, Kazuhiko Omori M.D., Ph.D.1, Hiromichi Osaka M.D., Ph.D.1, Koichi Sato MD.PhD.1, Naoki Mitsuhashi MD.PhD.1, Jun Mihara MD.PhD.2, Ken Ono MD.PhD.3 1Shizuoka Medical Research Center for Disaster, Juntendo University, Japan 2Izunokuni branch, Tagata Medical Association, Japan 3Izu Health and Medical Center, Japan *Corresponding author Youichi Yanagawa, M.D., Ph.D Email: [email protected] Abstract: The Disaster Imagination Game (DIG) is a newly developed method for disaster drills based on the knowledge of the Commanding Post Exercises of the Japan Self Defense Force, which uses maps and transparent overlay. The Izunokuni City office held a local liaison meeting for disaster medical care. The related organizations shared all information and confirmed the cooperating system for the huge disaster. In addition to providing information of various hazards created by the huge Nankai trough earthquake, the DIG was performed by the participants. The worst case scenario for such a huge Nankai Trough earthquake would be for a magnitude 9-class earthquake to hit the central and western parts of Japan. -

LIST of the WOOD PACKAGING MATERIAL PRODUCER for EXPORT 2007/2/10 Registration Number Registered Facility Address Phone

LIST OF THE WOOD PACKAGING MATERIAL PRODUCER FOR EXPORT 2007/2/10 Registration number Registered Facility Address Phone 0001002 ITOS CORPORATION KAMOME-JIGYOSHO 62-1 KAMOME-CHO NAKA-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-622-1421 ASAGAMI CORPORATION YOKOHAMA BRANCH YAMASHITA 0001004 279-10 YAMASHITA-CHO NAKA-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-651-2196 OFFICE 0001007 SEITARO ARAI & CO., LTD. TORIHAMA WAREHOUSE 12-57 TORIHAMA-CHO KANAZAWA-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-774-6600 0001008 ISHIKAWA CO., LTD. YOKOHAMA FACTORY 18-24 DAIKOKU-CHO TSURUMI-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-521-6171 0001010 ISHIWATA SHOTEN CO., LTD. 4-13-2 MATSUKAGE-CHO NAKA-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-641-5626 THE IZUMI EXPRESS CO., LTD. TOKYO BRANCH, PACKING 0001011 8 DAIKOKU-FUTO TSURUMI-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-504-9431 CENTER C/O KOUEI-SAGYO HONMOKUEIGYOUSHO, 3-1 HONMOKU-FUTO NAKA-KU 0001012 INAGAKI CO., LTD. HONMOKU B-2 CFS 045-260-1160 YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 0001013 INOUE MOKUZAI CO., LTD. 895-3 SYAKE EBINA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 046-236-6512 0001015 UTOC CORPORATION T-1 OFFICE 15 DAIKOKU-FUTO TSURUMI-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-501-8379 0001016 UTOC CORPORATION HONMOKU B-1 OFFICE B-1, HONMOKU-FUTOU, NAKA-KU, YOKOHAMA-SHI, KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-621-5781 0001017 UTOC CORPORATION HONMOKU D-5 CFS 1-16, HONMOKU-FUTOU, NAKA-KU, YOKOHAMA-SHI, KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-623-1241 0001018 UTOC CORPORATION HONMOKU B-3 OFFICE B-3, HONMOKU-FUTOU, NAKA-KU, YOKOHAMA-SHI, KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-621-6226 0001020 A.B. SHOUKAI CO., LTD. -

Izu Peninsula Geopark Promotion Council

Contents A. Identification of the Area ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 A.1 Name of the Proposed Geopark ........................................................................................................................................... 1 A.2 Location of the Proposed Geopark ....................................................................................................................................... 1 A.3 Surface Area, Physical and Human Geographical Characteristics ....................................................................................... 1 A.3.1 Physical Geographical Characteristics .......................................................................................................................... 1 A.3.2 Human Geographical Charactersitics ........................................................................................................................... 3 A.4 Organization in charge and Management Structure ............................................................................................................. 5 A.4.1 Izu Peninsula Geopark Promotion Council ................................................................................................................... 5 A.4.2 Structure of the Management Organization .................................................................................................................. 6 A.4.3 Supporting Units/ Members -

Cycle Train in Service! Rental Cycle Izu Vélo Shuzenji Station L G *The Required Time Shown Is the Estimated Time for an Electrical Assist Bicycle

Required time: about 4hours and 20minutes (not including sightseeing/rest time) Mishima Station Exploring in Mishima City - Hakone Pass - Numazu Station Atami Station Challenging Cyc Daiba Station course - Jukkoku Pass - Daiba Station Course START o lin Cycle Train in Service! Rental Cycle izu vélo Shuzenji Station l g *The required time shown is the estimated time for an electrical assist bicycle. é Izuhakone Railway 28 minutes Izuhakone Railway v M Izu-Nagaoka Station Cycle Train Service Zone JR Ito Line Izu City will host the cycling competition Mishima-Futsukamachi Station *Can be done in the opposite direction a Japan Cycle at the Olympic and Paralympic Games Tokyo 2020 ↑Ashinoko Lake u Sports Center About 1.3 km ( Track Race and Mountain Bicycle ) Hakone Pass z p Mishima Taisha Shrine i Hakone Ashinoko-guchi ◇Track Race Venue: Izu Velodrome ★ Minami Ito Line Izu City Susono About 2.2 km ★ ly the Heda Shuzenji Station Mountain Bicycle Venue: Izu Mountain Bicycle Course Grand Fields On ◇ p Country Club a i Nishikida Ichirizuka Historic Site z est u St b Nakaizu M u Toi Port Yugashima Gotemba Line nn Kannami Primeval Forest About 13.5 km v ing ♪ g s Izu Kogen Station é The train is National Historic Site: n V l i seat Joren Falls i ews! Hakone Pass o Enjoy the Izu l Mishima-Hagi Juka Mishima Skywalk Yamanaka Castle Ruins c n now departing! Lover’s Cape Ex ★ Izu Peninsula p About 8.7 km y Find the re C s bicycle that a s Children’s Forest Park Izukyu Express w Jukkoku Pass Rest House to the fullest! best for a Kannami Golf Club Tokai -

Housing Security Benefits Enquiries

Housing Security Benefits Enquiries Municipality Organisation Office Address Tel Fax Email Higashiizu Town Life Support and Consultation Higashiizu-cho Health and Welfare Centre Social Welfare 0557-22-1294 0557-23-0999 [email protected] Centre 306 Shirata, Higashiizu-cho, Kamo-gun Council Kawazucho Social Life Support and Consultation Kawazu-cho Health and Welfare Centre 0558-34-1286 0558-34-1312 [email protected] Welfare Council Centre 212-2 Tanaka, Kawazu-cho, Kamo-gun Minamiizu Town Life Support and Consultation Minamiizu-cho Martial Arts Hall Social Welfare 0558-62-3156 0558-62-3156 [email protected] Centre 590-1 Kano, Minamiizu-cho, Kamo-gun Council Matsuzaki Twon Life Support and Consultation Matsuzaki-cho General Welfare Centre Social Welfare 0558-42-2719 0558-42-2719 [email protected] Centre 272-2 Miyauchi, Matsuzaki-cho, Kamo-gun Council Nishiizu Town Life Support and Consultation Social Welfare 258-4 Ukusu, Nishiizu-cho, Kamo-gun 0558-55-1313 0558-55-1330 [email protected] Centre Council Kannami Town Life Support and Consultation Kannami-cho Health and Welfare Centre Social Welfare 055-978-9288 055-979-5212 [email protected] Centre 717-28 Hirai, Kannami-cho, Takata-gun Shizuoka Council Prefecture Shimizu Town Life Support and Consultation Shimizu-cho Welfare Centre Social Welfare 055-981-1665 055-981-0025 [email protected] Centre 221-1 Doiwa, Shimizu-cho, Sunto-gun Council Nagaizumi Town Nagaizumi Welfare Hall Support and Consultation Social Welfare 967-2 Shimochikari, -

Guidebook for Entering Senior High School in Shizuoka Prefecture

英語 Guidebook for entering Senior High School in Shizuoka Prefecture Fiscal 2012 < INDEX > I. The Japanese Educational System _________________________________________ 1 1. The Japanese Educational System 2. Who can take the entrance examination? II. Varieties of Senior High School ___________________________________________ 2 1. Specialized courses and licenses 2. Differences between public schools and private schools III. Fees of Senior High School _______________________________________________ 3 1. Examination fee, Entrance Fee, and other expenses to pay at the time of school entrance 2. Tuition, and other expenses 3. Other Expenses IV. Scholarships and Educational Loans _______________________________________ 4 V. The System of Student Selection __________________________________________ 6 VI. CHOSA-SHO (Student Information Sheet) ________________________________ 8 VII. The Schedule until the Entrance Examination ____________________________ 10 1. The Annual Schedule for the 3rd Grade Students of Junior High School 2. The Schedule of the Entrance Examination to Public Senior High Schools 3. The Schedule of the Entrance Examination to Private Senior High Schools VIII. About Educational Counseling ________________________________________ 11 IX. Terms used in High School or for Entrance Examinations ___________________ 12 <Public High Schools in Shizuoka Prefecture> _______________________________ 13 <Private High Schools in Shizuoka Prefecture> _______________________________ 17 Hamamatsu NPO Network Center 0 The Japanese Educational System 1. The Japanese Educational System Education prior to elementary school is optional. Education is compulsory from elementary school to junior high school, which totals 9 years. In elementary school and junior high school, there is generally no grade failure, but in high school and university, the student will not be promoted or will not be able to graduate when grades are not satisfactory, or the number of absent days passes a certain number. -

The 51St Annual Meeting of Japanese Society of Child Neurology

The 51st Annual Meeting of Japanese Society of Child Neurology May 28-30, 2009 Yonago Convention Center, Japan Yonago City Culture Hall, Japan PROGRAM 第51回日本小児神経学会総会英文.indd 1 2009/06/08 9:18:38 Thursday, May 28, 2009 Yonago Convention Center Venue A Venue B Venue C Venue D 1F Multi-purpose Hall 2F Small Hall 3F Conference Room No.2 3F Conference Room No.3 8:00 Presidential Lecture Opening Ceremony 9:00-9:30 9:00 Therapeutic strategy for neurogenetic disorders in childhood Presidential Lecture KOUSAKU OHNO Chair:KAZUIE IINUMA Keynote Lecture 1 9:30-10:00 Perspective of the medical treatments for the handicapped children MASATAKA ARIMA Chair:YUKIO FUKUYAMA 10:00 Keynote Lecture 2 10:00-10:30 Expectation for the Child Neurology derived from the Non-Profit Organization activity KENZO TAKESHITA Chair:SHIGEHIKO KAMOSHITA Special Lecture 1 10:30-11:20 Experience-dependent plasticity of the developing visual system 11:00 YOSHIO HATA Chair:TOYOJIRO MATSUISHI International Invited Lecture 1 11:20-12:20 Childhood white matter disorders ― from MRI patterns to disease genes 12:00 MARJO S VAN DER KNAAP Chair:MASAYA SEGAWA Luncheon Seminar 1 Luncheon Seminar 2 13:00 12:30-13:30 12:30-13:30 Chair:TAKAO TAKAHASHI Chair:ATSUO NEZU 14:00 International Invited Lecture 2 14:00-15:00 Botulinum toxin in the treatment for children with cerebral palsy ― update 2009 FLORIAN HEINEN Symposium 2 Chair:MAKIKO KAGA 14:00-16:00 15:00 Chair:HIDEO SUGIE Chair:EIJI NANBA acute encephalopathy 1(biomarker) 15:00-16:10 imaging analysis (O-001-007) 15:00-16:20 Chair:HIDETO -

Appendix (PDF:4.3MB)

APPENDIX TABLE OF CONTENTS: APPENDIX 1. Overview of Japan’s National Land Fig. A-1 Worldwide Hypocenter Distribution (for Magnitude 6 and Higher Earthquakes) and Plate Boundaries ..................................................................................................... 1 Fig. A-2 Distribution of Volcanoes Worldwide ............................................................................ 1 Fig. A-3 Subduction Zone Earthquake Areas and Major Active Faults in Japan .......................... 2 Fig. A-4 Distribution of Active Volcanoes in Japan ...................................................................... 4 2. Disasters in Japan Fig. A-5 Major Earthquake Damage in Japan (Since the Meiji Period) ....................................... 5 Fig. A-6 Major Natural Disasters in Japan Since 1945 ................................................................. 6 Fig. A-7 Number of Fatalities and Missing Persons Due to Natural Disasters ............................. 8 Fig. A-8 Breakdown of the Number of Fatalities and Missing Persons Due to Natural Disasters ......................................................................................................................... 9 Fig. A-9 Recent Major Natural Disasters (Since the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake) ............ 10 Fig. A-10 Establishment of Extreme Disaster Management Headquarters and Major Disaster Management Headquarters ........................................................................... 21 Fig. A-11 Dispatchment of Government Investigation Teams (Since -

LIST of the WOOD PACKAGING MATERIAL PRODUCER for EXPORT 2005/08/01 Registration Number Registered Facility Address Phone

LIST OF THE WOOD PACKAGING MATERIAL PRODUCER FOR EXPORT 2005/08/01 Registration number Registered Facility Address Phone 0001002 ITOS CORPORATION KAMOME‐JIGYOSHO 62‐1 KAMOME‐CHO NAKA‐KU YOKOHAMA‐SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045‐622‐1421 0001008 ISHIKAWA CO., LTD. YOKOHAMA FACTORY 18‐24 DAIKOKU‐CHO TSURUMI‐KU YOKOHAMA‐SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045‐521‐6171 THE IZUMI EXPRESS CO., LTD. TOKYO BRANCH, PACKING 0001011 8 DAIKOKU‐FUTO TSURUMI‐KU YOKOHAMA‐SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045‐504‐9431 CENTER HONMOKU B‐2 WARE HOUSE, HONMOKU D‐CFS 1 GO WARE HOUSE 3‐1 0001012 INAGAKI CO., LTD. HONMOKU WORKS 045‐260‐1160 HONMOKU‐FUTO NAKA‐KU YOKOHAMA‐SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 0001013 INOUE MOKUZAI CO., LTD. 895‐3 SYAKE EBINA‐SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 046‐236‐6512 B‐1, HONMOKU‐FUTOU, NAKA‐KU, YOKOHAMA‐SHI, KANAGAWA, 0001016 UTOC CORPORATION HONMOKU B‐1 OFFICE 045‐621‐5781 JAPAN 1‐16, HONMOKU‐FUTOU, NAKA‐KU, YOKOHAMA‐SHI, KANAGAWA, 0001017 UTOC CORPORATION HONMOKU D‐5 CFS 045‐623‐1241 JAPAN B‐3, HONMOKU‐FUTOU, NAKA‐KU, YOKOHAMA‐SHI, KANAGAWA, 0001018 UTOC CORPORATION HONMOKU B‐3 OFFICE 045‐621‐6226 JAPAN 0001020 A.B. SHOHKAI CO., LTD. EBINA‐JIGYOSHO 642 NAKANO EBINA‐SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 046‐239‐0133 0001023 OSAKI CORP. TATEBAYASHI EIGYOUSHO 358 NOBE‐MACHI TATEBAYASHI‐SHI GUNMA, JAPAN 0276‐74‐6531 0001024 OSAKI CORP. OYAMA EIGYOUSHO 4‐18‐39 JYOUTOU OYAMA‐SHI TOCHIGI, JAPAN 0285‐22‐1211 0001025 OSAKI CORP. NISHINASUNO EIGYOUSHO 429‐9 NIKU‐MACHI NISHINASUNO‐CHO NASU‐GUN TOCHIGI, JAPAN 0287‐37‐7161 C/O JFE ENGINEERING, 2-1 SUEHIRO-CHO TSURUMI-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI 0001027 ONOMIYA KOMPO UNYU CO., LTD. -

TOKAI Holdings / 3167

TOKAI Holdings / 3167 COVERAGE INITIATED ON: 2013.05.31 LAST UPDATE: 2019.08.26 Shared Research Inc. has produced this report by request from the company discussed in the report. The aim is to provide an “owner’s manual” to investors. We at Shared Research Inc. make every effort to provide an accurate, objective, and neutral analysis. In order to highlight any biases, we clearly attribute our data and findings. We will always present opinions from company management as such. Our views are ours where stated. We do not try to convince or influence, only inform. We appreciate your suggestions and feedback. Write to us at [email protected] or find us on Bloomberg. Research Coverage Report by Shared Research Inc. TOKAI Holdings / 3167 RCoverage LAST UPDATE: 2019.08.26 Research Coverage Report by Shared Research Inc. | www.sharedresearch.jp INDEX How to read a Shared Research report: This report begins with the trends and outlook section, which discusses the company’s most recent earnings. First-time readers should start at the business section later in the report. Executive summary ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Key financial data ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 Recent updates ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Highlights -

Medical Institutions Address Tel WEB Site 1

a list of medical institutions Hokkaido Medical Institutions Address Tel WEB Site Hakodate Shintoshi Hospital 331-1, Ishikawacho, Hakodate-shi, Hokkaido, 0138-46-1321 http://yushinkai.jp/hakodate/ (Japanese) 041-0802 Http://yushinkai.jp/hakodate/russia/ (Russian) Hakodate Municipal Hospital 1-10-1, Minatocho, Hakodate-shi, Hokkaido, 0138-43-2000 http://www.hospital.hakodate.hokkaido.jp/ 041-0821 (Japanese) Sapporo Higashi Tokushukai Hospital 14-3-1 Kita 33 Johigashi, Higashi-ku, Sapporo-shi, 011-722-1110 http://www.higashi-tokushukai.or.jp/ (Japanese) Hokkaido, 065-0033 Hokkaido Ohno Memorial Hospital 1-16-1 Miyanosawa 2 Jo, Nishi-ku, Sapporo-shi, 011-665-0020 https://ohno-kinen.jp/ (Japanese) Hokkaido, 063-0052 Kutchan-Kosei General Hospital 1-2 Kita 4 Johigashi, Kutchan, Abuta-gun, Hokkaido, 0136-22-1141 http://www.dou- 044-0004 kouseiren.com/byouin/kutchan/index.html (Japanese) Japanese Red Cross Asahikawa Hospital 1-1-1 Akebono 1 Jo, Asahikawa-shi, Hokkaido, 0166-22-8111 http://www.asahikawa.jrc.or.jp/ (Japanese) 070-8530 Shindo Hospital 19-Migi-6, 4 Jodori, Asahikawa-shi, Hokkaido, 0166-31-1221 https://shindo-hospital.or.jp (Japanese) 078-8214 Hokuto Hospital Kisen 7-5, Inadacho, Obihiro-shi, Hokkaido, 0155-48-8000 https://www.hokuto7.or.jp/patient/ (Japanese) 080-0833 Https://www.hokuto7.or.jp/mc/zh/ (Chinese) Kushiro City General Hospital 1-12, Shunkodai, Kushiro-shi, Hokkaido, 085-0822 0154-41-6121 http://www.kushiro-cghp.jp (Japanese) Hakodate Goryoukaku Hospital 38-3, Goryokakucho, Hakodate-shi, Hokkaido, 0138-51-2295 https://www.gobyou.com/ -

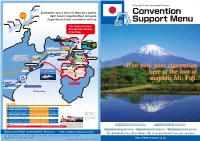

Convention Support Menu

Sapporo Shizuoka East Convention Bureau Excitement and a world of discovery awaits, Shizuoka Convention Sendai Prefecture right here in beautiful East Shizuoka. Kyoto Organize your next convention with us! Hiroshima Tok yo Support Menu Fukuoka The Shizuoka East Nagoya Convention Bureau Osaka Area Map Mt. Fuji Oyama Town Hakone Gotemba City Gotemba I.C. Susono City Shin-Tomei Expressway Nagaizumi Town Mishima Station Nagaizumi-Numazu I.C. Tomei Expressway Mishima City Numazu I.C. Shizuoka Shin-Shimizu JCT Kannami Shimizu Town Atami Atami Station Numazu Station Town City Prefecture Izunokuni Shimizu JCT City Shimizu Izu Hakone Railway Shizuoka Station Port Numazu City Shuzenji Station Izu-Jukan Expressway PlanPlan youryour nextnext conventionconvention Shizuoka I.C. Shuzenji I.C. Toi Izu City Port herehere atat thethe footfoot ofof Tsukigase I.C. To Hamamatsu, Nagoya Mt. Fuji Suruga-Bay Ferry majesticmajestic Mt.Mt. Fuji.Fuji. ← Sagara-Makinohara I.C. Shizuoka EAST Mt. Fuji Shizuoka Airport Tokaido Shinkansen Suruga Bay ACCESS ● From Tokyo (West Bound) Tokaido Shinkansen“Hikari” Tokyo Atami 37 mins Tokaido Shinkansen“Hikari” Tokyo Mishima 42 mins Spectacular views of Special Express“Odoriko” Tokyo Shuzenji 126 mins Mt. Fuji and the Southern Japanese Odakyu Romancecar“Fujisan” Shinjuku Gotemba 99 mins Alps at take-off and landing. 90-minute ● From Nagoya (East Bound) flight from Hokkaido Tokaido Shinkansen“Hikari” Nagoya Mishima 78 mins and Kyushu. Tokaido Shinkansen“Hikari” Nagoya Atami 85 mins ● By Air Convenient access & excellent facilities