Globalization and the Construction of Local Particularities: a Case Study of the Winnipeg Jets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ed Meagher Arena Unveiling

ED MEAGHER ARENA UNVEILING NOVEMBER 2013 NEWS RELEASE RENOVATED ED MEAGHER ARENA UNVEILED CONCORDIA STINGERS HIT THE ICE NHL STYLE Montreal, November 20, 2013 — Not only are the Concordia Stingers back on home ice after the reopening of the Ed Meagher Arena, they’re now competing on a brand new rink surface that conforms to National Hockey League specifications. The modernized arena features the latest and most cutting-edge technology on the market today — an eco-friendly carbon dioxide (CO2) ice refrigeration system. The technology, developed in Quebec, means the arena can operate 11 months a year, compared to seven using the former ammonia system. In addition to a new ice surface and boards, fans will appreciate the new heating system; the burning of natural gas has been replaced by recycled heat generated by the new refrigeration system. The renovations – made possible by a joint investment of $7.75 million from the Government of Quebec and Concordia — involved an expansion of 2,500 sq. ft. The new space boasts larger changing rooms, an equipment storage room, and two new changing rooms for soccer and rugby players. Other renovations include window replacements and a new ventilation and dehumidification system. ABOUT THE ED MEAGHER ARENA AND ITS ATHLETES The Ed Meagher Arena plays host to approximately 40 Stingers men’s and women’s hockey games a year. The Concordia hockey players proudly represent the university at an elite level competing against some of the best teams in North America. Over the years, many talented athletes — including Olympians and NHLers — have developed their skills as members of the Stingers or its founding institutions’ teams. -

36 Conference Championships

36 Conference Championships - 21 Regular Season, 15 Tournament TERRIERS IN THE NHL DRAFT Name Team Year Round Pick Clayton Keller Arizona Coyotes 2016 1 7 Since 1969, 163 players who have donned the scarlet Charlie McAvoy Boston Bruins 2016 1 14 and white Boston University sweater have been drafted Dante Fabbro Nashville Predators 2016 1 17 by National Hockey League organizations. The Terriers Kieffer Bellows New York Islanders 2016 1 19 have had the third-largest number of draftees of any Chad Krys Chicago Blackhawks 2016 2 45 Patrick Harper Nashville Predators 2016 5 138 school, trailing only Minnesota and Michigan. The Jack Eichel Buffalo Sabres 2015 1 2 number drafted is the most of any Hockey East school. A.J. Greer Colorado Avalanche 2015 2 39 Jakob Forsbacka Karlsson Boston Bruins 2015 2 45 Fifteen Terriers have been drafted in the first round. Jordan Greenway Minnesota Wild 2015 2 50 Included in this list is Rick DiPietro, who played for John MacLeod Tampa Bay Lightning 2014 2 57 Brandon Hickey Calgary Flames 2014 3 64 the Terriers during the 1999-00 season. In the 2000 J.J. Piccinich Toronto Maple Leafs 2014 4 103 draft, DiPietro became the first goalie ever selected Sam Kurker St. Louis Blues 2012 2 56 as the number one overall pick when the New York Matt Grzelcyk Boston Bruins 2012 3 85 Islanders made him their top choice. Sean Maguire Pittsburgh Penguins 2012 4 113 Doyle Somerby New York Islanders 2012 5 125 Robbie Baillargeon Ottawa Senators 2012 5 136 In the 2015 Entry Draft, Jack Eichel was selected Danny O’Regan San Jose Sharks 2012 5 138 second overall by the Buffalo Sabres. -

Guidelines for Arena Dasherboard & Shielding Systems

Guidelines For Arena Dasherboard & Shielding Systems May 2009 Notice This document is a preliminary draft. It has not been formally released by the ORFA and should not at this stage be construed to represent Association recommended best practice. It is being circulated for comment on its technical accuracy and policy implications. ORFA Guidelines for Arena Dasherboard and Shielding Systems v.09 Content Part-I – UNDERSTANDING ICE ARENA BOARDS & SHIELDING SYSTEMS 1.1 - Introduction 1.2 - Dasherboard History 1.3 - Current Trends 1.4 - CSA Guidelines for Spectator Safety in Indoor Arenas (CAN/CSA-Z262.7-04) 1.5 - CSA Definitions 1.6 - ORFA Definitions 1.7 - Protective Shielding Systems 1.8 - Dasherboard Anchoring Systems 1.9 - Dasherboard Cladding Systems 1.10 - Player, Penalty and Timekeeper Boxes 1.11 - Gates and Hardware Selection 1.12 - Minimum Protection Requirements 1.13 - CSA Protective Netting Testing Guidelines 1.14 - Suggested Guidelines for Selecting Protective Netting 1.15 - Signage and Warning 1.16 - Dasherboard Advertising 1.17 - Etching of Dasherboard Shielding 1.18 - Conversions 1.19 - Ice Floor Covers 1.20 - Conclusion Part-II SUGGESTED GUIDELINES FOR EVALUATING and MAINTAINING ARENA BOARDS & SHIELDING SYSTEMS Part-III SLEDGE HOCKEY ACCESSIBILITY: DESIGN GUIDELINES FOR ARENAS 1 ORFA - SUGGESTED GUIDELINES FOR ARENA DASHERBOARDS AND SHEILDING V.09 checklist of items that need to be PART I – UNDERSTANDING ICE considered as part of an ongoing systems ARENA BOARDS & SHIELDING review process. SYSTEMS The Ontario Recreation Facilities Association (ORFA) has attempted to collect information on the almost 60-year history and evolution of ice arena dasherboard and shielding systems. -

Télécharger La Page En Format

Portail de l'éducation de Historica Canada Canada's Game - The Modern Era Overview This lesson plan is based on viewing the Footprints videos for Gordie Howe, Bobby Orr, Father David Bauer, Bobby Hull,Wayne Gretzky, and The Forum. Throughout hockey's history, though they are not presented in the Footprints, francophone players like Guy Lafleur, Mario Lemieux, Raymond Bourque, Jacques Lemaire, and Patrick Roy also made a significant contribution to the sport. Parents still watch their children skate around cold arenas before the sun is up and backyard rinks remain national landmarks. But hockey is no longer just Canada's game. Now played in cities better known for their golf courses than their ice rinks, hockey is an international game. Hockey superstars and hallowed ice rinks became national icons as the game matured and Canadians negotiated their role in the modern era. Aims To increase student awareness of the development of the game of hockey in Canada; to increase student recognition of the contributions made by hockey players as innovators and their contributions to the game; to examine their accomplishments in their historical context; to explore how hockey has evolved into the modern game; to understand the role of memory and commemoration in our understanding of the past and present; and to critically investigate myth-making as a way of understanding the game’s relationship to national identity. Background Frozen fans huddled in the open air and helmet-less players battled for the puck in a -28 degree Celsius wind chill. The festive celebration was the second-ever outdoor National Hockey League game, held on 22 November 2003. -

“World Hockey Association Comin' on Strong” Rememb

™ FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Laurence Kaiser [email protected] Norb Ecksl [email protected] WORLD HOCKEY ASSOCIATION 50TH ANNIVERSARY REUNION LAS VEGAS – (January 22, 2021) To commemorate a very special day in sports history, many of the remaining members of the World Hockey Association, fans and celebrities will gather to celebrate the existence of the WHA that was born 50 years before. This reunion will take place in Las Vegas, Nevada from October 7, 2022 through October 11, 2022 where great and treasured moments will be fondly remembered. “WORLD HOCKEY ASSOCIATION COMIN’ ON STRONG” “The WHA means a lot to me and it was a very important part of my life. I look forward to being there and seeing everyone,” stated hockey legend Bobby Hull. “We are getting together for this great cause so that the WHA is remembered for the things it did for the game of hockey. I will enjoy reminiscing and hope that many of you will join me to celebrate.” Hull, the Golden Jet, is committed to the cause and will be in Las Vegas for the entire celebration. We are also honoring the godfather of the WHA and the original “disruptor” of professional sports, Dennis A. Murphy, along with other luminaries. REMEMBERING “A DAY THAT CHANGED THE GAME” The WHA had a great impact in changing the game of hockey in North America and abroad when the impossible happened. The fledgling league challenged the long- established National Hockey League (NHL), and for seven seasons presented an entertaining version of our great game. It all started as the puck dropped on October 11, 1 1972, when the Alberta Oilers defeated the Ottawa Nationals, 7-4, and the Cleveland Crusaders shutout the Quebec Nordiques, 2-0. -

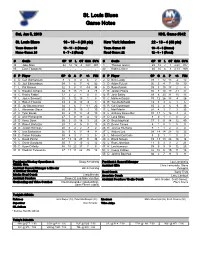

St. Louis Blues Game Notes

St. Louis Blues Game Notes Sat, Jan 5, 2019 NHL Game #642 St. Louis Blues 16 - 18 - 4 (36 pts) New York Islanders 22 - 13 - 4 (48 pts) Team Game: 39 10 - 11 - 2 (Home) Team Game: 40 10 - 5 - 3 (Home) Home Game: 24 6 - 7 - 2 (Road) Road Game: 22 12 - 8 - 1 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 34 Jake Allen 32 14 12 4 3.03 .901 1 Thomas Greiss 23 12 7 1 2.63 .917 85 Evan Fitzpatrick - - - - - - 40 Robin Lehner 20 10 6 3 2.13 .929 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 4 D Carl Gunnarsson 8 0 0 0 6 2 2 D Nick Leddy 39 1 12 13 -2 12 6 D Joel Edmundson 34 1 6 7 -6 52 3 D Adam Pelech 36 3 4 7 10 10 7 L Pat Maroon 32 3 8 11 -14 34 6 D Ryan Pulock 39 3 15 18 2 4 10 C Brayden Schenn 34 7 15 22 -9 28 7 R Jordan Eberle 35 7 10 17 -11 12 15 C Robby Fabbri 17 2 2 4 0 0 12 R Josh Bailey 39 8 23 31 13 13 17 L Jaden Schwartz 25 3 12 15 1 8 13 C Mathew Barzal 39 12 26 38 -4 26 18 C Robert Thomas 33 4 9 13 -5 8 14 R Tom Kuhnhackl 19 3 3 6 1 6 19 D Jay Bouwmeester 34 1 6 7 -11 20 15 R Cal Clutterbuck 35 2 4 6 -5 36 20 L Alexander Steen 30 6 9 15 -1 10 17 L Matt Martin 28 4 3 7 3 25 21 C Tyler Bozak 38 6 11 17 -4 10 18 L Anthony Beauvillier 38 11 5 16 -1 4 27 D Alex Pietrangelo 27 5 8 13 -6 12 21 D Luca Sbisa 8 0 1 1 0 2 29 D Vince Dunn 36 3 13 16 3 23 24 D Scott Mayfield 37 3 11 14 12 40 41 D Robert Bortuzzo 20 1 4 5 0 13 25 D Devon Toews 5 1 0 1 5 0 43 D Jordan Schmaltz 20 0 2 2 -7 2 26 R Joshua Ho-Sang 9 1 1 2 2 4 49 C Ivan Barbashev 36 5 6 11 -9 9 27 L Anders Lee 39 14 14 28 10 33 55 D Colton Parayko 38 8 3 11 3 6 28 L Michael Dal Colle 5 0 1 1 0 0 57 L David Perron 37 13 14 27 0 34 29 C Brock Nelson 39 13 13 26 14 14 70 C Oskar Sundqvist 30 7 3 10 -2 12 32 L Ross Johnston 11 0 3 3 2 21 90 C Ryan O'Reilly 38 15 22 37 7 6 47 R Leo Komarov 39 5 9 14 12 26 91 R Vladimir Tarasenko 37 11 11 22 -15 18 53 C Casey Cizikas 32 10 5 15 11 18 55 D Johnny Boychuk 38 2 7 9 5 9 President of Hockey Operations & Doug Armstrong President & General Manager Lou Lamoriello GM/Alt. -

2009-2010 Colorado Avalanche Media Guide

Qwest_AVS_MediaGuide.pdf 8/3/09 1:12:35 PM UCQRGQRFCDDGAG?J GEF³NCCB LRCPLCR PMTGBCPMDRFC Colorado MJMP?BMT?J?LAFCÍ Upgrade your speed. CUG@CP³NRGA?QR LRCPLCRDPMKUCQR®. Available only in select areas Choice of connection speeds up to: C M Y For always-on Internet households, wide-load CM Mbps data transfers and multi-HD video downloads. MY CY CMY For HD movies, video chat, content sharing K Mbps and frequent multi-tasking. For real-time movie streaming, Mbps gaming and fast music downloads. For basic Internet browsing, Mbps shopping and e-mail. ���.���.���� qwest.com/avs Qwest Connect: Service not available in all areas. Connection speeds are based on sync rates. Download speeds will be up to 15% lower due to network requirements and may vary for reasons such as customer location, websites accessed, Internet congestion and customer equipment. Fiber-optics exists from the neighborhood terminal to the Internet. Speed tiers of 7 Mbps and lower are provided over fiber optics in selected areas only. Requires compatible modem. Subject to additional restrictions and subscriber agreement. All trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Copyright © 2009 Qwest. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS Joe Sakic ...........................................................................2-3 FRANCHISE RECORD BOOK Avalanche Directory ............................................................... 4 All-Time Record ..........................................................134-135 GM’s, Coaches ................................................................. -

1988-1989 Panini Hockey Stickers Page 1 of 3 1 Road to the Cup

1988-1989 Panini Hockey Stickers Page 1 of 3 1 Road to the Cup Calgary Flames Edmonton Oilers St. Louis Blues 2 Flames logo 50 Oilers logo 98 Blues logo 3 Flames uniform 51 Oilers uniform 99 Blues uniform 4 Mike Vernon 52 Grant Fuhr 100 Greg Millen 5 Al MacInnis 53 Charlie Huddy 101 Brian Benning 6 Brad McCrimmon 54 Kevin Lowe 102 Gordie Roberts 7 Gary Suter 55 Steve Smith 103 Gino Cavallini 8 Mike Bullard 56 Jeff Beukeboom 104 Bernie Federko 9 Hakan Loob 57 Glenn Anderson 105 Doug Gilmour 10 Lanny McDonald 58 Wayne Gretzky 106 Tony Hrkac 11 Joe Mullen 59 Jari Kurri 107 Brett Hull 12 Joe Nieuwendyk 60 Craig MacTavish 108 Mark Hunter 13 Joel Otto 61 Mark Messier 109 Tony McKegney 14 Jim Peplinski 62 Craig Simpson 110 Rick Meagher 15 Gary Roberts 63 Esa Tikkanen 111 Brian Sutter 16 Flames team photo (left) 64 Oilers team photo (left) 112 Blues team photo (left) 17 Flames team photo (right) 65 Oilers team photo (right) 113 Blues team photo (right) Chicago Blackhawks Los Angeles Kings Toronto Maple Leafs 18 Blackhawks logo 66 Kings logo 114 Maple Leafs logo 19 Blackhawks uniform 67 Kings uniform 115 Maple Leafs uniform 20 Bob Mason 68 Glenn Healy 116 Alan Bester 21 Darren Pang 69 Rolie Melanson 117 Ken Wregget 22 Bob Murray 70 Steve Duchense 118 Al Iafrate 23 Gary Nylund 71 Tom Laidlaw 119 Luke Richardson 24 Doug Wilson 72 Jay Wells 120 Borje Salming 25 Dirk Graham 73 Mike Allison 121 Wendel Clark 26 Steve Larmer 74 Bobby Carpenter 122 Russ Courtnall 27 Troy Murray -

Jets Forced to Return Home After Real Whiteout Closes Minneapolis Airport

Winnipeg Free Press https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/sports/hockey/jets/snowstorm-closes-minneapolis-airport- forces-jets-plane-to-land-in-duluth-479777143.html Jets forced to return home after real whiteout closes Minneapolis airport By: Mike McIntyre It was a white out on the highway near Monticello, Minnesota this morning. Free Press photographer Trevor Hagan was on his way to Minneapolis to cover the Jets/Wild playoff series. They've handled the Minnesota Wild in the first two games off their playoff series, but the Winnipeg Jets have proven to be no match for Mother Nature. A record-setting spring snowstorm meant the Jets were unable to land in Minneapolis Saturday afternoon and forced the charter flight to be diverted to Duluth, 250 kilometres northeast. After sitting on the tarmac for a couple hours waiting to see if an opportunity to get into the Twin Cities might open up, a decision was made to turn the plane around and head back to Winnipeg by late afternoon. All planes were grounded at the Minneapolis-St. Paul airport for much of the day as the area was under a blizzard warning, with some estimates of more than 30 centimetres of snow. The Jets will now fly out of Winnipeg Sunday morning, which is a major change to normal game- day routine. The puck is set to drop for Game 3 at 6 p.m. in St Paul, with the Jets up 2-0 in the best-of-seven series. Winnipeg held a brief practice and media availability Saturday morning at the Bell MTS Iceplex, moving up the time because of the storm system. -

Season IV: 1975-1976

Season IV: Jets Capture First Crown Tardif & Cloutier Scoring Stars 1975-1976 Fighting Mars League Image The World Hockey Association opened its fourth season with high hopes after Award Winners three previous seasons of steadily increasing attendance figures. Two teams would not be back for the 1975-76 campaign: the Chicago Cougars folded immediately after the previous season’s end, and the Baltimore Blades ceased operations not long after. In their places were two expansion franchises: the Cincinnati Stingers and the Denver Spurs. There was just one franchise shift: the Vancouver Blazers moved across the Rockies to Calgary, becoming the Cowboys. The fourteen teams were divided into three divisions. Calgary, Edmonton, Québec, Toronto and Winnipeg made up the Canadian Division; Cincinnati, Cleveland, Indianapolis and New England comprised the Eastern Division, Most Valuable Player Rookie of the Year Gordie Howe Trophy Lou Kaplan Trophy while the Western Division included Denver, Houston, Minnesota, Phoenix and Marc Tardif Mark Napier San Diego. Québec Toronto Denver’s Spurs could not make it to the new year; they vacated Denver at the end of December, played two home games in Ottawa in early January 1976, and disbanded altogether two weeks later. Six weeks after Ottawa’s departure, the Minnesota Fighting Saints folded, paring the league to twelve teams. The patchwork schedule used for the remainder of the season saw some teams play 81 games so that other teams could reach 80. Disparities abounded: Québec and Toronto tangled 16 times, while Winnipeg and San Diego squared off on only three occasions. Best Goaltender Best Defenseman Winnipeg and Québec fought hard for the top spot in the Canadian Division, Ben Hatskin Trophy Dennis Murphy Trophy Winnipeg squeaking ahead with 106 points, two ahead of Québec. -

Pregame Notes

PREGAME NOTES 2019 TIM HORTONS NHL HERITAGE CLASSIC WINNIPEG JETS vs. CALGARY FLAMES MOSAIC STADIUM, REGINA, SASK. – OCT. 26, 2019 JETS, FLAMES FACE OFF OUTDOORS The Winnipeg Jets and Calgary Flames face off tonight in the 2019 Tim Hortons NHL Heritage Classic (10 p.m. ET / 8 p.m. CST, CBC, SN1, CITY, TVAS2, NBCSN) – the League’s 28th regular-season outdoor game and fifth in the Heritage Classic series. The Jets and Flames each have participated in one prior outdoor game, both under the Heritage Classic umbrella. Winnipeg played host to the 2016 Tim Hortons NHL Heritage Classic at Investors Group Field, falling 3-0 to the Edmonton Oilers. Nine Jets players who appeared in that game remain with the team: Kyle Connor, Nikolaj Ehlers, Connor Hellebuyck, Patrik Laine, Adam Lowry, Josh Morrissey, Mathieu Perreault, Mark Scheifele and Blake Wheeler. Current Calgary goaltender Cam Talbot started for Edmonton in that contest, stopping all 31 shots he faced for the third shutout in outdoor NHL game history. Current Jets forward Mark Letestu scored the winning goal (while shorthanded), as a member of the Oilers. And current Flames forward Milan Lucic recorded two penalty minutes for Edmonton. Calgary served as hosts for the 2011 Tim Hortons NHL Heritage Classic at McMahon Stadium, defeating the Montreal Canadiens 4-0. Two players who appeared in that game remain with the Flames: Mikael Backlund and Mark Giordano. Overall, the Jets feature 11 players who have participated in a prior outdoor NHL game (minimum: 1 GP in 2019-20), while the Flames have four. Talbot leads that group with four such appearances, though he served as a backup goaltender for three of them (2014 SS w/ NYR [2 GP], 2019 SS w/ PHI). -

Citizenship Study Materials for Newcomers to Manitoba: Based on the 2011 Discover Canada Study Guide

Citizenship Study Materials for Newcomers to Manitoba: Based on the 2011 Discover Canada Study Guide Table of Contents ____________________________________________________________________________ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I TIPS FOR THE VOLUNTEER FACILITATOR II READINGS: 1. THE OATH OF CITIZENSHIP .........................................................................................1 2. WHO WE ARE ...............................................................................................................7 3. CANADA'S HISTORY (PART 1) ...................................................................................13 4. CANADA'S HISTORY (PART 2) ...................................................................................20 5. CANADA'S HISTORY (PART 3) ...................................................................................26 6. MODERN CANADA ....................................................................................................32 7. HOW CANADIANS GOVERN THEMSELVES (PART 1) .............................................. 40 8. HOW CANADIANS GOVERN THEMSELVES (PART 2) .............................................. 45 9. ELECTIONS (PART 1) ................................................................................................. 50 10. ELECTIONS (PART 2) ...............................................................................................55 11. OTHER LEVELS OF GOVERNMENT IN CANADA ................................................... 60 12. HOW MUCH DO YOU KNOW ABOUT YOUR GOVERNMENT? ..............................