Media Ownership Hearing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 12, 2002 Issue

April 12, 2002 Volume 16 Issue '89 $6.00 ASHANTI IF it COMES FROM the HEART, THENyouKNOW that IT'S TRUE... theCOLORofLOVE "The guys went back to the formula that works...with Babyface producing it and the greatest voices in music behind it ...it's a smash..." Cat Thomas KLUC/Las Vegas "Vintage Boyz II Men, you can't sleep on it...a no brainer sound that always works...Babyface and Boyz II Men a perfect combination..." Byron Kennedy KSFM/Sacramento "Boyz II Men is definitely bringin that `Boyz II Men' flava back...Gonna break through like a monster!" Eman KPWR/Los Angeles PRODUCED by BABYFACE XN SII - fur Sao 1 III\ \\Es.It iti viNA! ARM&SNykx,aristo.coni421111211.1.ta Itccoi ds. loc., a unit of RIG Foicrtainlocni. 1i -r by Q \Mil I April 12, 2002 Volume 16 Issue 789 DENNIS LAVINTHAL Publisher ISLAND HOPPING LENNY BEER Editor In Chief No man is an Island, but this woman is more than up to the task. TONI PROFERA Island President Julie Greenwald has been working with IDJ ruler Executive Editor Lyor Cohen so long, the two have become a tag team. This week, KAREN GLAUBER they've pinned the charts with the #1 debut of Ashanti's self -titled bow, President, HITS Magazine three other IDJ titles in the Top 10 (0 Brother, Ludcaris and Jay-Z/R. TODD HENSLEY President, HITS Online Ventures Kelly), and two more in the Top 20 (Nickelback and Ja Rule). Now all she has to do is live down this HITS Contents appearance. -

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, et al. For Consent to Assignment of Licenses of ) BALH-20070627ACN ) BALH-20070627ACO, et al. Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; ) BAL-20070906ADP CC Licenses, LLC; AMFM Radio ) BALH-20070906ADQ Licenses, LLC; Citicasters Licenses, LP; ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; and ) Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. ) Federal Communications Commission ERRATUM Released: January 30, 2008 By the Media Bureau: On January 24, 2008, the Commission released a Memorandum Opinion and Order(MO&O),FCC 08-3, in the above-captioned proceeding. -

2018 Town Report

2018 Annual Report Annual Town Meeting - March 5, 2019 Annual Representative Town Meeting - March 23, 2019 Brattleboro,Vermont Town and Town School District Fiscal Year Budgets (7/1/19 to 6/30/20) Fiscal Year Audits (7/1/17 to 6/30/18) 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS TOWN OF BRATTLEBORO BRATTLEBORO TOWN SCHOOL DISTRICT Page Page Table of Contents…………………… ............................................... 1 Town Departments, Schools & Other Services…………………… .. 2 WSESU Child Find Notice for All Parents…………… ................. 164 Town Personnel … .......................................................................... 3 Report of School Board and Administrators ................................ 164 Town Officers (prior to 3/5/19 elections) ………………… ............... 4 Faculty and Staff .......................................................................... 166 Town Meeting Members (prior to 3/5/19 elections)………. ............. 5 School Age Enrollment Chart……………………………………… 167 Warnings, Annual Town and Town School District Budget Summary of Revenues, Expenses & Reserve Funds, Meeting, March 5, 2019 ............................................................. 6 Recommendation to the WSEUUSD Transition Board ............. 168 Warnings from Selectboard, Annual Representative Town Three Prior Years Comparison…………………………. ............... 169 Meeting, March 23, 2019 ........................................................... 6 Budget Expenditure Detail…………………………. ...................... 170 Warnings from Town School District, Annual Representative Windham Southeast -

Jessie J.Pdf

Jessie J Jessica Ellen Cornish was born on 27th of March 1988 in Redbridge, London in UK. Her stage name is Jessie J. Jessie began singing with 11 years in showbusiness. She appeared in a West End production of Whistle Down the Wind by Andrew Lloyd Webber. She attended Colin’s Performing Arts School. At the age of 16 she began studying musical theater at the BRIT School, and joined a girl group called Soul Deep at the age of 17. She sang there for 2 years and then she left the group and became an independent singer. Young Jessie J When she was 17 she wrote her first song, Big white room, which has become a signature song for her. She wrote it after she was hospitalized while sharing a room with a younger boy who later sadly lost his life. Her life is very ordinary. She is the youngest of three children and she is a singer and songwriter. She sings R&B, soul, pop and hip – hop. Her father is a social worker and her mother is kindergarten teacher. Her sister Hanna is a fotographer and her second sister Rachel is a childminder. 2006–2009: Career beginnings She had signed on with now-defunct Gut Records, having fallen to bankruptcy. She now has a publishing arrangement with SONY ATV and shows great promise as a writer. Her song, Sexy Silk, was picked by Nivea for a campaign. She has also written for Chris Brown and Lisa Lois. Jessie J was responsible for making Miley Cyrus’ song’s, one of them is Party In The USA which is one of her greatests hits. -

What Will Be Country Music's Songs of Summer 2021?

2021 MAY 24 CountryInsider.com | Sign Up For Daily Email Here What Will Be Country Music’s Songs Of Summer 2021? If 2020 was the summer where everyone stayed home, 2021 will be the one where people can’t wait to get back out. With Memorial Day Weekend approaching, what are country radio’s programmers seeing as the singles for this season? “I think three are shaping up to be summer soundtracks with Luke Bryan’s ‘Waves’ front and center,” says Audacy Country Format Captain Tim Roberts. “It’s a super-chill track that captures summer and fun beautifully.” Also on Roberts’ summer fun list: Brian Kelley’s “Beach Cowboy,” “which I think is where a lot of brains drift toward daydreaming about summer beach fun,” and Old Dominion’s new “I Was on a Boat That Day.” (Continued on page 4) COUNTRY INSIDER TOP 5: WGAR’s “Wazz & Carletta” Look Back On Morning Show Pairing Ahead Of First Anniversary. Bobby Bones Show’s Eddie Garcia Blows Past $10K Goal To Walk From West Virginia To Tennessee. Morgan Wallen Debuts Miranda Lambert, Nicolle Galyon Co-Write On Instagram. Consultant Mike O’Malley: Don’t Be A Bystander In Your Own Show. Dustin Lynch Returns As Headliner for WEZL Charlotte’s Stars and Guitars Music Festival. 1 | MAY 24, 2021 CountryInsider.com Dani Lynn Howe Trey Poston Top 5 All-Time Middays/KYKR Top 5 All-Time Songs Leuck & Howe Morning Show, WLLR-FM Country Bands: Beaumont, TX by Female Artists: Quad Cities, IA/IL 1. Restless Heart 1. Safe in the Arms of Love - Martina McBride 2. -

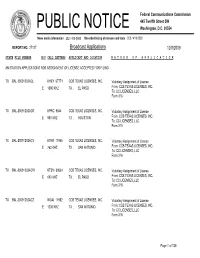

Broadcast Applications 12/8/2009

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 27127 Broadcast Applications 12/8/2009 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING TX BAL-20091202ACL KHEY 67771 CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License E 1380 KHZ TX , EL PASO From: CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. To: CC LICENSES, LLC Form 316 TX BAL-20091202ACR KPRC 9644 CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License E 950 KHZ TX , HOUSTON From: CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. To: CC LICENSES, LLC Form 316 TX BAL-20091202ACV KTKR 11945 CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License E 760 KHZ TX , SAN ANTONIO From: CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. To: CC LICENSES, LLC Form 316 TX BAL-20091202ACW KTSM 69561 CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License E 690 KHZ TX , EL PASO From: CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. To: CC LICENSES, LLC Form 316 TX BAL-20091202ACZ WOAI 11952 CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License E 1200 KHZ TX , SAN ANTONIO From: CCB TEXAS LICENSES, INC. To: CC LICENSES, LLC Form 316 Page 1 of 139 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 27127 Broadcast Applications 12/8/2009 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING WA BAL-20091202ADB KHHO 18523 ACKERLEY BROADCASTING Voluntary Assignment of License OPERATIONS, LLC E 850 KHZ From: ACKERLEY BROADCASTING OPERATIONS, LLC WA , TACOMA To: CITICASTERS LICENSES, INC. -

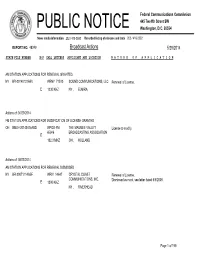

Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED NY BR-20140131ABV WENY 71510 SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Renewal of License. E 1230 KHZ NY ,ELMIRA Actions of: 04/29/2014 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MODIFICATION OF LICENSE GRANTED OH BMLH-20140415ABD WPOS-FM THE MAUMEE VALLEY License to modify. 65946 BROADCASTING ASSOCIATION E 102.3 MHZ OH , HOLLAND Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL DISMISSED NY BR-20071114ABF WRIV 14647 CRYSTAL COAST Renewal of License. COMMUNICATIONS, INC. Dismissed as moot, see letter dated 5/5/2008. E 1390 KHZ NY , RIVERHEAD Page 1 of 199 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED NY BAL-20140212AEC WGGO 9409 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: PEMBROOK PINES, INC. E 1590 KHZ NY , SALAMANCA To: SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Form 314 NY BAL-20140212AEE WOEN 19708 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. -

When Being No. 1 Is Not Enough

A Report Prepared by the Civil Rights Forum on Communications Policy When Being No. 1 Is Not Enough: The Impact of Advertising Practices On Minority- Owned & Minority-Formatted Broadcast Stations Kofi Asiedu Ofori Principal Investigator submitted to the Office of Communications Business Opportunities Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. All Rights Reserved to the Civil Rights Forum on Communications Policy a project of the Tides Center Synopsis As part of its mandate to identify and eliminate market entry barriers for small businesses under Section 257 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, the Federal Communications Commission chartered this study to investigate practices in the advertising industry that pose potential barriers to competition in the broadcast marketplace. The study focuses on practices called "no Urban/Spanish dictates" (i.e. the practice of not advertising on stations that target programming to ethnic/racial minorities) and "minority discounts" (i.e. the practice of paying minority- formatted radio stations less than what is paid to general market stations with comparable audience size). The study consists of a qualitative and a quantitative analysis of these practices. Based upon comparisons of nationwide data, the study indicates that stations that target programming to minority listeners are unable to earn as much revenue per listener as stations that air general market programming. The quantitative analysis also suggests that minority-owned radio stations earn less revenues per listener than majority broadcasters that own a comparable number of stations nationwide. These disparities in advertising performance may be attributed to a variety of factors including economic efficiencies derived from common ownership, assessments of listener income and spending patterns, or ethnic/racial stereotypes that influence the media buying process. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Pat Paxton in PHOENIX Airplay Leaders the Interview Page 3 Page 17 Page 33

POWER Entercom’s IS FORTY 31 PAT PAXTON IN PHOENIX Airplay Leaders The Interview PAGE 3 PAGE 17 PAGE 33 SEPTEMBER 2008 Guitar Heroes: Tim Hattrick (l) and Willy D. Loon (r) don the KNIX logo suits and bookend PD Alan Sledge. KNIX IS 4 In Phoenix hen Buck Owens bought KNIX-FM in Phoenix for $75,000, few could have imagined the extent to which his station’s commitment to country and to its listeners would succeed. At its peak, the station Wwas beyond dominant and, more important, perhaps the most influential and trendsetting Country station ever on the FM dial. As KNIX celebrates its 40th anniversary, Country Aircheck contacted several current and former executives for their favorite recollections of the station Buck built. and 30 Dolly Parton look-alike contestants paraded onstage Michael Owens, KNIX GM 1978-1999: before more than 1,000 listeners who had jammed into the Sometime in early 1979 – about a year after I became General club. Unfortunately, another 500 couldn’t get in because the Manager of KNIX-AM/FM – we were struggling with ratings place was filled! We had a couple people from RCA/Nashville and revenue. We were 10th or 12th at the time, trying hard to (Dolly’s label at the time) as judges, along with local newspaper break through to become a player in this big Phoenix market. We and TV celebrities. Local TV stations covered it live and the came up with an idea for a promotion and teamed with a local Phoenix Gazette newspaper ran a front-page photo plus a two- independent gasoline company to sell gas at 10 cents per gallon. -

Through the Iris TH Wasteland SC Because the Night MM PS SC

10 Years 18 Days Through The Iris TH Saving Abel CB Wasteland SC 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10,000 Maniacs 1,2,3 Redlight SC Because The Night MM PS Simon Says DK SF SC 1975 Candy Everybody Wants DK Chocolate SF Like The Weather MM City MR More Than This MM PH Robbers SF SC 1975, The These Are The Days PI Chocolate MR Trouble Me SC 2 Chainz And Drake 100 Proof Aged In Soul No Lie (Clean) SB Somebody's Been Sleeping SC 2 Evisa 10CC Oh La La La SF Don't Turn Me Away G0 2 Live Crew Dreadlock Holiday KD SF ZM Do Wah Diddy SC Feel The Love G0 Me So Horny SC Food For Thought G0 We Want Some Pussy SC Good Morning Judge G0 2 Pac And Eminem I'm Mandy SF One Day At A Time PH I'm Not In Love DK EK 2 Pac And Eric Will MM SC Do For Love MM SF 2 Play, Thomas Jules And Jucxi D Life Is A Minestrone G0 Careless Whisper MR One Two Five G0 2 Unlimited People In Love G0 No Limits SF Rubber Bullets SF 20 Fingers Silly Love G0 Short Dick Man SC TU Things We Do For Love SC 21St Century Girls Things We Do For Love, The SF ZM 21St Century Girls SF Woman In Love G0 2Pac 112 California Love MM SF Come See Me SC California Love (Original Version) SC Cupid DI Changes SC Dance With Me CB SC Dear Mama DK SF It's Over Now DI SC How Do You Want It MM Only You SC I Get Around AX Peaches And Cream PH SC So Many Tears SB SG Thugz Mansion PH SC Right Here For You PH Until The End Of Time SC U Already Know SC Until The End Of Time (Radio Version) SC 112 And Ludacris 2PAC And Notorious B.I.G. -

MADONNA WORLD TOUR 2012 Final 2.7.2012 300Am ET LN Templatex

MADONNA WORLD TOUR 2012 th Tickets Go On Sale in Israel and the UK Feb 10 th North American Tickets Go On Sale Beginning Feb. 13 LOS ANGELES, CA (February 7, 2012) - Madonna is having a huge party and everyone’s invited. The Madonna 2012 World Tour begins May 29 th 2012 in Tel Aviv, Israel it was officially announced by Live Nation Entertainment, the tour’s international promoter. The shows will include arenas, stadiums and special outdoor sights including the Plains of Abraham in Quebec and a return visit to South America as well as Australia where she has not performed in 20 years. The tour will stop in 26 European cities including London, Paris, Milan and Berlin. The first of 26 North American shows is scheduled for August 28 th in Philadelphia and includes a September 6 th show in NY’s Yankee Stadium and an October l0th performance at LA’s Staples Center. Tickets are scheduled to go on sale beginning February 10 th in Tel Aviv and the United Kingdom, with North American tickets going on sale beginning February 13 th . Tickets for North America are available at Ticketmaster.com and LiveNation.com . A complete itinerary of Madonna 2012 follows this release. Madonna’s previous tour, the phenomenally successful “Sticky & Sweet” Tour reaffirmed her status as one of the most successful touring artists of all time. The historic tour included such incredible touring feats as a 70,000 seat sell-out in Werchter, Belgium, an 85,000 sell-out in Helsinki (the largest show ever in the Nordic countries by a solo artist), a 40,000 ticket sell-out in Oslo, Norway, and 72,000 tickets sold out in one day in Tallinn Estonia.