The Four Vertex Theorem and Its Converse Dennis Deturck, Herman Gluck, Daniel Pomerleano, and David Shea Vick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 1.7B the Four-Vertex Theorem

Section 1.7B The Four-Vertex Theorem Matthew Hendrix Matthew Hendrix Section 1.7B The Four-Vertex Theorem Definition The integer I is called the rotation index of the curve α where I is an integer multiple of 2π; that is, Z 1 k(s) dt = θ(`) − θ(0) = 2πI 0 Definition 2 Let α : [0; `] ! R be a plane closed curve given by α(s) = (x(s); y(s)). Since s is the arc length, the tangent vector t(s) = (x0(s); y 0(s)) has unit length. The tangent indicatrix is 2 0 0 t : [0; `] ! R , which is given by t(s) = (x (s); y (s)); this is a differentiable curve, the trace of which is contained in the circle of radius 1. Matthew Hendrix Section 1.7B The Four-Vertex Theorem Definition 2 Let α : [0; `] ! R be a plane closed curve given by α(s) = (x(s); y(s)). Since s is the arc length, the tangent vector t(s) = (x0(s); y 0(s)) has unit length. The tangent indicatrix is 2 0 0 t : [0; `] ! R , which is given by t(s) = (x (s); y (s)); this is a differentiable curve, the trace of which is contained in the circle of radius 1. Definition The integer I is called the rotation index of the curve α where I is an integer multiple of 2π; that is, Z 1 k(s) dt = θ(`) − θ(0) = 2πI 0 Matthew Hendrix Section 1.7B The Four-Vertex Theorem Definition 2 A vertex of a regular plane curve α :[a; b] ! R is a point t 2 [a; b] where k0(t) = 0. -

Evolutes of Curves in the Lorentz-Minkowski Plane

Evolutes of curves in the Lorentz-Minkowski plane 著者 Izumiya Shuichi, Fuster M. C. Romero, Takahashi Masatomo journal or Advanced Studies in Pure Mathematics publication title volume 78 page range 313-330 year 2018-10-04 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10258/00009702 doi: info:doi/10.2969/aspm/07810313 Evolutes of curves in the Lorentz-Minkowski plane S. Izumiya, M. C. Romero Fuster, M. Takahashi Abstract. We can use a moving frame, as in the case of regular plane curves in the Euclidean plane, in order to define the arc-length parameter and the Frenet formula for non-lightlike regular curves in the Lorentz- Minkowski plane. This leads naturally to a well defined evolute asso- ciated to non-lightlike regular curves without inflection points in the Lorentz-Minkowski plane. However, at a lightlike point the curve shifts between a spacelike and a timelike region and the evolute cannot be defined by using this moving frame. In this paper, we introduce an alternative frame, the lightcone frame, that will allow us to associate an evolute to regular curves without inflection points in the Lorentz- Minkowski plane. Moreover, under appropriate conditions, we shall also be able to obtain globally defined evolutes of regular curves with inflection points. We investigate here the geometric properties of the evolute at lightlike points and inflection points. x1. Introduction The evolute of a regular plane curve is a classical subject of differen- tial geometry on Euclidean plane which is defined to be the locus of the centres of the osculating circles of the curve (cf. [3, 7, 8]). -

Symmetrization of Convex Plane Curves

Symmetrization of convex plane curves P. Giblin and S. Janeczko Abstract Several point symmetrizations of a convex curve Γ are introduced and one, the affinely invariant ‘cen- tral symmetric transform’ (CST) with respect to a given basepoint inside Γ, is investigated in detail. Examples for Γ include triangles, rounded triangles, ellipses, curves defined by support functions and piecewise smooth curves. Of particular interest is the region of basepoints for which the CST is convex (this region can be empty but its complement in the interior of Γ is never empty). The (local) boundary of this region can have cusps and in principle it can be determined from a geometrical construction for the tangent direction to the CST. MR Classification 52A10, 53A04 1 Introduction There are several ways in which a convex plane curve Γ can be transformed into one which is, in some sense, symmetric. Here are three possible constructions. PT Assume that Γ is at least C1. For each pair of parallel tangents of Γ construct two parallel lines with the same separation and the origin (or any other fixed point) equidistant from them. The resulting envelope, the parallel tangent transform, will be symmetric about the chosen fixed point. All choices of fixed point give the same transform up to translation. This construction is affinely invariant. A curve of constant width, where the separation of parallel tangent pairs is constant, will always transform to a circle. Another example is given in Figure 1(a). This construction can also be interpreted in the following way: Reflect Γ in the chosen fixed point 1 to give Γ∗ say. -

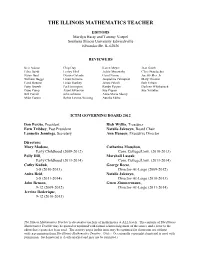

The Illinois Mathematics Teacher

THE ILLINOIS MATHEMATICS TEACHER EDITORS Marilyn Hasty and Tammy Voepel Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Edwardsville, IL 62026 REVIEWERS Kris Adams Chip Day Karen Meyer Jean Smith Edna Bazik Lesley Ebel Jackie Murawska Clare Staudacher Susan Beal Dianna Galante Carol Nenne Joe Stickles, Jr. William Beggs Linda Gilmore Jacqueline Palmquist Mary Thomas Carol Benson Linda Hankey James Pelech Bob Urbain Patty Bruzek Pat Herrington Randy Pippen Darlene Whitkanack Dane Camp Alan Holverson Sue Pippen Sue Younker Bill Carroll John Johnson Anne Marie Sherry Mike Carton Robin Levine-Wissing Aurelia Skiba ICTM GOVERNING BOARD 2012 Don Porzio, President Rich Wyllie, Treasurer Fern Tribbey, Past President Natalie Jakucyn, Board Chair Lannette Jennings, Secretary Ann Hanson, Executive Director Directors: Mary Modene, Catherine Moushon, Early Childhood (2009-2012) Com. College/Univ. (2010-2013) Polly Hill, Marshall Lassak, Early Childhood (2011-2014) Com. College/Univ. (2011-2014) Cathy Kaduk, George Reese, 5-8 (2010-2013) Director-At-Large (2009-2012) Anita Reid, Natalie Jakucyn, 5-8 (2011-2014) Director-At-Large (2010-2013) John Benson, Gwen Zimmermann, 9-12 (2009-2012) Director-At-Large (2011-2014) Jerrine Roderique, 9-12 (2010-2013) The Illinois Mathematics Teacher is devoted to teachers of mathematics at ALL levels. The contents of The Illinois Mathematics Teacher may be quoted or reprinted with formal acknowledgement of the source and a letter to the editor that a quote has been used. The activity pages in this issue may be reprinted for classroom use without written permission from The Illinois Mathematics Teacher. (Note: Occasionally copyrighted material is used with permission. Such material is clearly marked and may not be reprinted.) THE ILLINOIS MATHEMATICS TEACHER Volume 61, No. -

One-Dimensional Projective Structures, Convex Curves and the Ovals of Benguria & Loss

published version: Comm. Math. Phys. 336 (2015), 933-952 One-dimensional Projective Structures, Convex Curves and the Ovals of Benguria & Loss JACOB BERNSTEIN AND THOMAS METTLER ABSTRACT. Benguria and Loss have conjectured that, amongst all smooth closed curves in R2 of length 2, the lowest possible eigenvalue of the op- erator L 2 is 1. They observed that this value was achieved on a D C two-parameter family, O, of geometrically distinct ovals containing the round circle and collapsing to a multiplicity-two line segment. We characterize the curves in O as absolute minima of two related geometric functionals. We also discuss a connection with projective differential geometry and use it to explain the natural symmetries of all three problems. 1. Introduction In[ 1], Benguria and Loss conjectured that for any, , a smooth closed curve in R2 2 of length 2, the lowest eigenvalue, , of the operator L satisfied D C 1 1. That is, they conjectured that for all such and all functions f H ./, 2 Z Z 2 2 2 2 (1.1) f f ds f ds; jr j C where f is the intrinsic gradient of f , is the geodesic curvature and ds is the lengthr element. This conjecture was motivated by their observation that it was equivalent to a certain one-dimensional Lieb-Thirring inequality with conjectured sharp constant. They further observed that the above inequality is saturated on a two-parameter family of strictly convex curves which contains the round circle and degenerates into a multiplicity-two line segment. The curves in this family look like ovals and so we call them the ovals of Benguria and Loss and denote the family by 1 O. -

Asymptotic Approximation of Convex Curves

Asymptotic Approximation of Convex Curves Monika Ludwig Abstract. L. Fejes T´othgave asymptotic formulae as n → ∞ for the distance between a smooth convex disc and its best approximating inscribed or circumscribed polygons with at most n vertices, where the distance is in the sense of the symmetric difference metric. In this paper these formulae are extended by specifying the second terms of the asymptotic expansions. Tools are from affine differential geometry. 1 Introduction 2 i Let C be a closed convex curve in the Euclidean plane IE and let Pn(C) be the set of all convex polygons with at most n vertices that are inscribed in C. We i measure the distance of C and Pn ∈ Pn(C) by the symmetric difference metric δS and study the asymptotic behaviour of S i S i δ (C, Pn) = inf{δ (C, Pn): Pn ∈ Pn(C)} S c as n → ∞. In case of circumscribed polygons the analogous notion is δ (C, Pn). For a C ∈ C2 with positive curvature function κ(t), the following asymptotic formulae were given by L. Fejes T´oth [2], [3] Z l !3 S i 1 1/3 1 δ (C, Pn) ∼ κ (t)dt as n → ∞ (1) 12 0 n2 and Z l !3 S c 1 1/3 1 δ (C, Pn) ∼ κ (t)dt as n → ∞, (2) 24 0 n2 where t is the arc length and l the length of C. Complete proofs of these results are due to D. E. McClure and R. A. Vitale [9]. In this article we extend these asymptotic formulae by deriving the second terms in the asymptotic expansions. -

The Implementation of Ict on Various Curves Through

THE IMPLEMENTATION OF ICT ON VARIOUS CURVES THROUGH WINPLOT J.Sengamala Selvi,1,* Dr.T.Venugopal 2 1Asst.Professor, Dept.of Mathematics, SCSVMV University, Enathur, Tamilnadu, Kanchipuram, India. 2Professor of Mathematics, Director, Research and Publications, SCSVMV University, Enathur, Kanchipuram, Tamilnadu, India. E-mail: [email protected]. ABSTRACT: ml This paper aims to take a step further into the 2. Click on the link: Winplot for Windows development and innovation of teaching, 95/98/ME/2K/XP (558K) using contemporary instruments, which 3. When prompted, click save to save the develops the necessary skills of the student file to the desktop. community. To introduce the Win plot 4. Double click the icon wp32z.exe on the software in making teaching mathematical desktop. problems into an easier one so as to cheer up 5. WinZip will prompt to extract the files to the students to develop their application C:\peanut. Click “Unzip”. oriented skills. This paper deals with the hope 6. Win Plot is now installed in C:\peanut that the mathematics classroom will soon be directory. converted into modern classroom where software oriented learning will take place in the near future. KEYWORDS: Higher education Mathematics, ICT, Mathematics pedagogy.Win plot software 1. Introduction: ICT is one of the factors to shaping and changing the world rapidly.ICT has also brought a paradigm shift in education. It touches every aspect of Education.ICT has brought a new networks of teachers and learners connecting them throughout the globe.ICT is a means of accessing, processing, sharing, editing, selecting, B.BASICS OF WINPLOT presenting, communicating through the The first time Win Plot is used, the screen information in a variety of media. -

An Investigation of the Four Vertex Theorem and Its Converse Rebeka Kelmar Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2017 An Investigation of the Four Vertex Theorem and its Converse Rebeka Kelmar Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Geometry and Topology Commons Recommended Citation Kelmar, Rebeka, "An Investigation of the Four Vertex Theorem and its Converse" (2017). Honors Theses. 52. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/52 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Investigation of the Four Vertex Theorem and its Converse By Rebeka Kelmar *************** Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Mathematics UNION COLLEGE March, 2017 Abstract In the study of curves there are many interesting theorems. One such theorem is the four vertex theorem and its converse. The four vertex theorem says that any simple closed curve, other than a circle, must have four vertices. This means that the curvature of the curve must have at least four local maxima/minima. In my project I explore different proofs of the four vertex theorem and its history. I also look at a modified converse of the four vertex theorem which says that any continuous real- valued function on the circle that has at least two local maxima and two local minima is the curvature function of a simple closed curve in the plane. -

Classification of Convex Ancient Solutions to Curve Shortening Flow on the Sphere

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Classification of Convex Ancient Solutions to Curve Shortening Flow on the Sphere Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7gt6c9nw Author Louie, Janelle Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Classification of Convex Ancient Solutions to Curve Shortening Flow on the Sphere A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Mathematics by Janelle Louie Committee in charge: Professor Bennett Chow, Chair Professor Kenneth Intriligator Professor Elizabeth Jenkins Professor Lei Ni Professor Jeffrey Rabin 2014 Copyright Janelle Louie, 2014 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Janelle Louie is approved, and it is ac- ceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page.................................. iii Table of Contents................................. iv List of Figures..................................v Acknowledgements................................ vi Vita........................................ vii Abstract of the Dissertation........................... viii Chapter 1 Introduction............................1 1.1 Previous work and background...............2 1.2 Results and outline of the thesis..............4 Chapter 2 Preliminaries...........................6 2.1 -

Isoptics of a Closed Strictly Convex Curve. - II Rendiconti Del Seminario Matematico Della Università Di Padova, Tome 96 (1996), P

RENDICONTI del SEMINARIO MATEMATICO della UNIVERSITÀ DI PADOVA W. CIESLAK´ A. MIERNOWSKI W. MOZGAWA Isoptics of a closed strictly convex curve. - II Rendiconti del Seminario Matematico della Università di Padova, tome 96 (1996), p. 37-49 <http://www.numdam.org/item?id=RSMUP_1996__96__37_0> © Rendiconti del Seminario Matematico della Università di Padova, 1996, tous droits réservés. L’accès aux archives de la revue « Rendiconti del Seminario Matematico della Università di Padova » (http://rendiconti.math.unipd.it/) implique l’accord avec les conditions générales d’utilisation (http://www.numdam.org/conditions). Toute utilisation commerciale ou impression systématique est constitutive d’une infraction pénale. Toute copie ou impression de ce fichier doit conte- nir la présente mention de copyright. Article numérisé dans le cadre du programme Numérisation de documents anciens mathématiques http://www.numdam.org/ Isoptics of a Closed Strictly Convex Curve. - II. W. CIE015BLAK (*) - A. MIERNOWSKI (**) - W. MOZGAWA(**) 1. - Introduction. ’ This article is concerned with some geometric properties of isoptics which complete and deepen the results obtained in our earlier paper [3]. We therefore begin by recalling the basic notions and necessary results concerning isoptics. An a-isoptic Ca of a plane, closed, convex curve C consists of those points in the plane from which the curve is seen under the fixed angle .7r - a. We shall denote by C the set of all plane, closed, strictly convex curves. Choose an element C and a coordinate system with the ori- gin 0 in the interior of C. Let p(t), t E [ 0, 2~c], denote the support func- tion of the curve C. -

Moon in a Puddle and the Four-Vertex Theorem

Moon in a puddle and the four-vertex theorem Anton Petrunin and Sergio Zamora Barrera with artwork by Ana Cristina Chavez´ Caliz´ Abstract. We present a proof of the moon in a puddle theorem, and use its key lemma to prove a generalization of the four-vertex theorem. arXiv:2107.08455v1 [math.DG] 18 Jul 2021 INTRODUCTION. The theorem about the Moon in a puddle provides the simplest meaningful example of a local-to-global theorem which is mainly what differential geometry is about. Yet, the theorem is surprisingly not well-known. This paper aims to redress this omission by calling attention to the result and applying it to a well-known theorem MOON IN A PUDDLE. The following question was initially asked by Abram Fet and solved by Vladimir Ionin and German Pestov [10]. Theorem 1. Assume γ is a simple closed smooth regular plane curve with curvature bounded in absolute value by 1. Then the region surrounded by γ contains a unit disc. We present the proof from our textbook [12] which is a slight improvement of the original proof. Both proofs work under the weaker assumption that the signed curva- ture is at most one, assuming that the sign is chosen suitably. A more general statement for a barrier-type bound on the curvature was given by Anders Aamand, Mikkel Abra- hamsen, and Mikkel Thorup [1]. There are other proofs. One is based on the curve- shortening flow; it is given by Konstantin Pankrashkin [8]. Another one uses cut locus; it is sketched by Victor Toponogov [13, Problem 1.7.19]; see also [11]. -

Writhe - Four Vertex Theorem.14 June, 2006

Writhe - Four Vertex Theorem.14 June, 2006 THE FOUR VERTEX THEOREM AND ITS CONVERSE in honor of Björn Dahlberg The Four Vertex Theorem says that a simple closed curve in the plane, other than a circle, must have at least four "vertices", that is, at least four points where the curvature has a local maximum or local minimum. There must be at least two local maxima, separated by two local minima. 1 The Converse to the Four Vertex Theorem says that any continuous real-valued function on the circle which has at least two local maxima and two local minima is the curvature function of a simple closed curve in the plane. Preassign curvature ..... then find the curve That is, given such a function κ defined on the circle S1 , 1 2 there is an embedding α: S → R whose image has 1 curvature κ(t) at the point α(t) for all t ∊ S . 2 History. In 1909, the Indian mathematician S. Mukhopadhyaya proved the Four Vertex Theorem for strictly convex curves in the plane. Syamadas Mukhopadhyaya (1866 - 1937) 3 In 1912, the German mathematician Adolf Kneser proved it for all simple closed curves in the plane, not just the strictly convex ones. Adolf Kneser (1862 - 1930) In 1971, we proved the converse for strictly positive preassigned curvature, as a special case of a general result about the existence of embeddings of Sn into Rn+1 with strictly positive preassigned Gaussian curvature. 4 In 1997, the Swedish mathematician Björn Dahlberg proved the full converse to the Four Vertex Theorem without the restriction that the curvature be strictly positive.