Consumer Behaviour in Relation to Traditional Food a Thesis Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bayou Boogaloo Authentic Cajun & Creole Cuisine

120 West Main Street, Norfolk, Virginia 23510 P: 757.441.2345 • W: festevents.org • E: [email protected] Media Release Media Contact: Erin Barclay For Immediate Release [email protected] P: 757.441.2345 x4478 Nationally Known New Orleans Chefs Serve Up Authentic Cajun & Creole Cuisine at 25th Annual Bayou Boogaloo and Cajun Food Festival presented by AT&T Friday, June 20 – Sunday, June 22, 2014 Town Point Park, Downtown Norfolk Waterfront, VA • • • NORFOLK, VA – (May 27, 2014) – Nothing says New Orleans like the uniquely delicious delicacies and distinctive flavor of Cajun & Creole cuisine! Norfolk Festevents is bringing nationally known chefs straight from New Orleans to Norfolk to serve up the heart and soul of Louisiana food dish by dish at the 25th Annual AT&T Bayou Boogaloo & Cajun Food Festival starting Friday, June 20- Sunday, June 22, 2014 in Town Point Park in Downtown Norfolk, VA. Norfolk’s annual “second line” with New Orleans’ unique culture spices it up this year with the addition of multiple New Orleans chefs that are sure to bring that special spirit to life in Town Point Park. Cooking up their famous cajun & creole cuisines are Ms. Linda The Ya-ka-Mein Lady, Chef Curtis Moore from the Praline Connection, Chef Woody Ruiz, New Orleans Crawfish King Chris “Shaggy” Davis, Jacques-Imo’s Restaurant, Edmond Nichols of Direct Select Seafood, Chef Troy Brucato, Cook Me Somethin’ Mister Jambalaya and more! They have been featured on such television shows as Anthony Bourdain’s “No Reservations”, Food Networks highly competitive cooking competition “Chopped”, “Food Paradise” and “The Best Thing I Ever Ate”. -

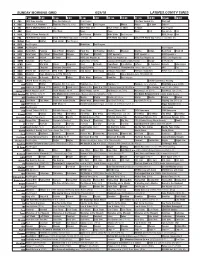

TV Listings Aug21-28

SATURDAY EVENING AUGUST 21, 2021 B’CAST SPECTRUM 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 1 AM 2 2Stand Up to Cancer (N) NCIS: New Orleans ’ 48 Hours ’ CBS 2 News at 10PM Retire NCIS ’ NCIS: New Orleans ’ 4 83 Stand Up to Cancer (N) America’s Got Talent “Quarterfinals 1” ’ News (:29) Saturday Night Live ’ Grace Paid Prog. ThisMinute 5 5Stand Up to Cancer (N) America’s Got Talent “Quarterfinals 1” ’ News (:29) Saturday Night Live ’ 1st Look In Touch Hollywood 6 6Stand Up to Cancer (N) Hell’s Kitchen ’ FOX 6 News at 9 (N) News (:35) Game of Talents (:35) TMZ ’ (:35) Extra (N) ’ 7 7Stand Up to Cancer (N) Shark Tank ’ The Good Doctor ’ News at 10pm Castle ’ Castle ’ Paid Prog. 9 9MLS Soccer Chicago Fire FC at Orlando City SC. Weekend News WGN News GN Sports Two Men Two Men Mom ’ Mom ’ Mom ’ 9.2 986 Hazel Hazel Jeannie Jeannie Bewitched Bewitched That Girl That Girl McHale McHale Burns Burns Benny 10 10 Lawrence Welk’s TV Great Performances ’ This Land Is Your Land (My Music) Bee Gees: One Night Only ’ Agatha and Murders 11 Father Brown ’ Shakespeare Death in Paradise ’ Professor T Unforgotten Rick Steves: The Alps ’ 12 12 Stand Up to Cancer (N) Shark Tank ’ The Good Doctor ’ News Big 12 Sp Entertainment Tonight (12:05) Nightwatch ’ Forensic 18 18 FamFeud FamFeud Goldbergs Goldbergs Polka! Polka! Polka! Last Man Last Man King King Funny You Funny You Skin Care 24 24 High School Football Ring of Honor Wrestling World Poker Tour Game Time World 414 Video Spotlight Music 26 WNBA Basketball: Lynx at Sky Family Guy Burgers Burgers Burgers Family Guy Family Guy Jokers Jokers ThisMinute 32 13 Stand Up to Cancer (N) Hell’s Kitchen ’ News Flannery Game of Talents ’ Bensinger TMZ (N) ’ PiYo Wor. -

The Walking Dead,” Which Starts Its Final We Are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant Season Sunday on AMC

Las Cruces Transportation August 20 - 26, 2021 YOUR RIDE. YOUR WAY. Las Cruces Shuttle – Taxi Charter – Courier Veteran Owned and Operated Since 1985. Jeffrey Dean Morgan Call us to make is among the stars of a reservation today! “The Walking Dead,” which starts its final We are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant season Sunday on AMC. Call us at 800-288-1784 or for more details 2 x 5.5” ad visit www.lascrucesshuttle.com PHARMACY Providing local, full-service pharmacy needs for all types of facilities. • Assisted Living • Hospice • Long-term care • DD Waiver • Skilled Nursing and more Life for ‘The Walking Dead’ is Call us today! 575-288-1412 Ask your provider if they utilize the many benefits of XR Innovations, such as: Blister or multi-dose packaging, OTC’s & FREE Delivery. almost up as Season 11 starts Learn more about what we do at www.rxinnovationslc.net2 x 4” ad 2 Your Bulletin TV & Entertainment pullout section August 20 - 26, 2021 What’s Available NOW On “Movie: We Broke Up” “Movie: The Virtuoso” “Movie: Vacation Friends” “Movie: Four Good Days” From director Jeff Rosenberg (“Hacks,” Anson Mount (“Hell on Wheels”) heads a From director Clay Tarver (“Silicon Glenn Close reunited with her “Albert “Relative Obscurity”) comes this 2021 talented cast in this 2021 actioner that casts Valley”) comes this comedy movie about Nobbs” director Rodrigo Garcia for this comedy about Lori and Doug (Aya Cash, him as a professional assassin who grapples a straight-laced couple who let loose on a 2020 drama that casts her as Deb, a mother “You’re the Worst,” and William Jackson with his conscience and an assortment of week of uninhibited fun and debauchery who must help her addict daughter Molly Harper, “The Good Place”), who break up enemies as he tries to complete his latest after befriending a thrill-seeking couple (Mila Kunis, “Black Swan”) through four days before her sister’s wedding but decide job. -

'Tremendously Misunderstood'

$1 Serving our communities since 1889 — www.chronline.com Mid-Week Edition Snow Blankets Thursday, County / Main 16 Jan. 12, 2017 Lighting Up the City Tribe Buoys Dock Plans Fort Borst Christmas Display Raises More Chehalis Tribe Makes Donation Toward New Than $20,000, Six Tons of Food / Main 4 Wheelchair Ramp at Fort Borst Pond / Main 7 Citizen Group, City Make Amends on Resources for Homeless Justyna Tomtas OPEN ARMS: Councilors gized to the Centralia City tion to that to come to some sort / [email protected] Council on behalf of the group of agreement or resolution,” he Chris Shilley, of Express Support for for the organization’s act of civil said regarding the ordinance Open Arms, Homeless Population disobedience after they decided that prohibited their actions. addresses the Cen- to attach items to trees at George He said he’d like to come tralia City Council After Removal of Items Washington Park following city up with an agreement on a on Tuesday night From Park staff’s removal of the clothing timeframe when the organiza- about the group’s based on a city ordinance. tion would be allowed to hang eforts to help the By Justyna Tomtas After apologizing to the up items, which include hats, homeless popula- [email protected] council, Shilley asked the city to scarves and mittens, at Wash- tion in the city. work with the group in their fu- ington Park to help the local On Tuesday night, Chris ture efforts. Shilley, of Open Arms, apolo- “I’m here to ask for an exemp- please see GROUP, page Main 13 Lewis Gather Church Feeds, County ‘Tremendously Clothes and Supports Centralia’s Growing Might Homeless Population Replace Misunderstood’ Manager Living in Arizona TRAVEL: Current Risk Manager Moved Last Year, Stayed With County at Request of Commissioners By Aaron Kunkler [email protected] Lewis County may begin searching for a replacement risk manager following Pau- lette Young’s move to Arizo- na in September. -

Sunday Morning Grid 6/24/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/24/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Special (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Program House House 1st Look Extra Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX FIFA World Cup Today 2018 FIFA World Cup Japan vs Senegal. (N) FIFA World Cup Today 2018 FIFA World Cup Poland vs Colombia. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Belton Real Food Food 50 28 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Kid Stew Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La casa de mi padre (2008, Drama) Nosotr. Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Buen Provecho!

www.oeko-tex.com International OEKO-TEX® Cookbook | Recipes from all over the world | 2012 what´scooking? mazaidar khanay ka shauk Guten Appetit! Trevlig måltid Buen provecho! Smacznego 尽享美食 Καλή σας όρεξη! Enjoy your meal! Dear OEKO-TEX® friends The OEKO-TEX® Standard 100 is celebrating its 20th anniversary this year. We would like to mark this occasion by saying thank you to all companies participating in the OEKO-TEX® system, and to their employees involved in the OEKO-TEX® product certification in their daily work. Without their personal commitment and close co-operation with our teams around the globe, the great success of the OEKO-TEX® Standard 100 would not have been possible. As a small gift the OEKO-TEX® teams from our worldwide member institutes and representative offices have created a self-made cooking book with favourite recipes which in some way has the same properties as the OEKO-TEX® Standard 100 that you are so familiar with – it is international, it can be used as a modular system and it illustrates the great variety of delicious food and drinks (just like the successfully tested textiles of all kinds). We hope that you will enjoy preparing the individual dishes. Set your creativity and your taste buds free! Should you come across any unusual ingredients or instructions, please feel free to call the OEKO-TEX® employees who will be happy to provide an explanation – following the motto “OEKO-TEX® unites and speaks Imprint the same language” (albeit sometimes with a local accent). Publisher: Design & Layout: Bon appetit! -

International Association of Culinary Professionals 26Th Annual Conference April 21-24, 2004 Baltimore, Maryland

International Association of Culinary Professionals 26th Annual Conference April 21-24, 2004 Baltimore, Maryland General Session “Is Globalization Changing The Way The World Eats?” Speaker: Dr. Tyler Cowen Thank you all, and good morning. Let’s start with slide one. That’s me, the obsessive, and obsessive is the key word here. I’m food obsessive. I have several obsessions actually, but today we talk about food. When I get home, my wife will ask me, “how did it go?”, and my answer will be, “the breakfast was excellent!” So I travel a great deal, I cook a great deal, and I write an on-line dining guide. I’m one of those people who lives to eat. For a long time now, I have been writing about culture, and creativity, and diversity, and now I am writing about food. And my interest in food really stems from my life, and that is from my obsessive nature. I wanted to be going out there, eating in the best places possible. With this attitude every meal counts. But if every meal is going to count, you have to know how to eat. So let’s go to the next slide. I have a theory of food. It’s a fairly simple theory, it’s not perfect, and there are some exceptions. But what makes for great food? Three items: You need competition, experimentation, and pride. Competition – if you are in a strange city, or strange country, and you want to know where to eat, go to the cuisine that is represented by the greatest number of restaurants. -

We Need Our Own Andrew Carnegie Thought of a Permanent Local Concert Hall Remains Enticing

The Voice of the West Village WestView News VOLUME 14, NUMBER 1 JANUARY 2018 $1.00 We Need Our Own Andrew Carnegie thought of a permanent local concert hall remains enticing. Yes, our audience is very gray and, I think, that is not just because these concerts are free to seniors but because our audience mostly learns about the concerts from the pages of WestView. Doorman-guarded condo towers do not accept WestView; you either have to own a townhouse or live in a rent-regulated tenement to get WestView. Our younger staffers lecture me continu- ously on ‘social media’ and they are doing things to make us available online, which I don’t understand and am impatient to learn. But still, you must write words that have to be read whether it is on a computer CLOSED TO PRAYER, OPEN TO INSPIRATION: Again on Saturday, December 23rd, the shuttered St. Veronica Church was opened and screen or on paper. filled for a concert sponsored by WestView News in its efforts to create a permanent West Village concert hall free to seniors. Photo by © But back to the concerts! They cost Joel Gordon 2017 - All rights reserved. money—about $25,000 per concert—and By George Capsis Despite the rain, you came and again in There is no doubt now that superb clas- so far we have been asking friends to do- great numbers and filled all the seats in the sical music played by the very best musi- nate. However, we have pretty much run On December 23rd, WestView gave an- main sanctuary. -

¶O – Lelo's Video Competition Is a Celebration for Each Student's Hard

FOR THE WEEK OF MARCH 19 - 25, 2017 THE GREAT INDEX TO FUN DINING • ARTS • MUSIC • NIGHTLIFE Look for it every Friday in the HIGHLIGHTS THIS WEEK to Arby’s in a new episode of “Baskets,” airing Thurs- SUNDAY TUESDAY day on FX. Co-created by Galifianakis, Louis C.K. Elementary Bull and Jonathan Krisel, the comedy chronicles the life KGMB 9:00 p.m. KGMB 8:00 p.m. of a man who dreams of becoming a French clown. Sherlock (Jonny Lee Miller) and Dr. Watson (Lucy Michael Weatherly stars as Jason Bull, the brilliant FRIDAY Liu) take on another case in a new episode of “Elemen- doctor behind one of the most prolific trial consulting Grimm tary,” airing today on CBS. Inspired by the firms of all time in this rebroadcast of "Bull," airing iconic detective created by Sir Arthur Co- Tuesday on CBS. Bull uses psychology, intu- KHNL 7:00 p.m. nan Doyle, this new updated version of ition and high-tech data to learn what makes jurors, at- the mystery series takes place in mod- torneys and others tick. A dark force with its sights set on Diana (Hannah R. ern-day New York. Loyd) arrives in Portland, fulfiling the prophecy in this new episode of “Grimm,” airing Friday on WEDNESDAY NBC. Nick (David Giuntoli) and Capt. Renard (Sasha MONDAY Empire Roiz) must work together in order to protect her. Dancing With the Stars KHON 8:00 p.m. KITV 7:00 p.m. SATURDAY Lucious (Terrence Howard) launches an at- The Godfather Celebrities, athletes and other tack on Angelo (Taye Diggs), then announc- public figures team up with pro- es his new music project called Inferno in AMC 12:00 p.m. -

Good City Brewing Commits to Century City Business Park

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Good City Brewing Commits to Century City Business Park MILWAUKEE (July 25, 2018) – Good City Brewing announced it is moving its corporate offices and warehouse operations to the Century City Business Park located on Milwaukee’s northwest side. Good City is the first business to commit to the high profile city-led redevelopment project. Located near W. Capitol Drive and N. 31st on Milwaukee’s Northwest Side, Century City 1 is a 53,160 sf flex industrial building that was co-developed by General Capital Group and the City of Milwaukee. The facility represents the first phase of a planned business park initiated by the City of Milwaukee to spur economic development in the central city. The state of the art facility has not had a permanent occupant since its completion in 2016. Good City Co-Founder Dan Katt notes that breweries are often the first movers in spurring economic development. “From our Farwell location that had sat vacant for 5 years to our future downtown location that is literally being built from the ground up, we have been about breathing life into underutilized spaces. Our conviction is that the current downtown renaissance should create ripple effects benefitting the entire city. “ According to Katt, Century City provides an immediate business solution. “We’ve expanded our brewery 4 times in the 2 years since we opened our doors, and we are simply out of space on the east side. The demand for our beer, especially our flagship Motto Mosaic Pale Ale, and the growth that comes with it, is very exciting.” Pending approval from City leaders, Good City will purchase the building through an affiliate entity and begin to move operations into the building immediately. -

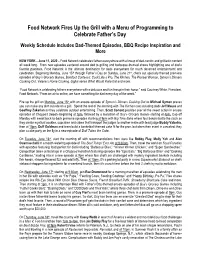

Food Network Fires up the Grill with a Menu of Programming to Celebrate Father’S Day

Food Network Fires Up the Grill with a Menu of Programming to Celebrate Father’s Day Weekly Schedule Includes Dad-Themed Episodes, BBQ Recipe Inspiration and More NEW YORK – June 11, 2020 – Food Network celebrates fathers everywhere with a lineup of dad-centric and grilltastic content all week long. From new episodes centered around dad to grilling and barbeque-themed shows highlighting one of dad’s favorite pastimes, Food Network is the ultimate destination for dads everywhere for much deserved entertainment and celebration. Beginning Monday, June 15th through Father’s Day on Sunday, June 21st, check out specially themed premiere episodes of Guy’s Grocery Games, Barefoot Contessa: Cook Like a Pro, The Kitchen, The Pioneer Woman, Symon’s Dinners Cooking Out, Valerie’s Home Cooking, digital series What Would Katie Eat and more. “Food Network is celebrating fathers everywhere with a delicious and fun lineup in their honor,” said Courtney White, President, Food Network. “From on-air to online, we have something for dad every day of the week.” Fire up the grill on Monday, June 15th with an encore episode of Symon’s Dinners Cooking Out as Michael Symon proves you can make any dish outside on a grill. Spend the rest of the morning with The Kitchen cast including dads Jeff Mauro and Geoffrey Zakarian as they celebrate outdoor entertaining. Then, Scott Conant presides over all the sweet action in encore episodes of Chopped Sweets beginning at 1pm, followed by a marathon of Guy’s Grocery Games starting at 4pm. Cap off Monday with sweet back-to-back premiere episodes starting at 9pm with Big Time Bake where four bakers battle the clock as they create mystical cookies, cupcakes and cakes that transport the judges to another realm with lead judge Buddy Valastro, then at 10pm, Duff Goldman and team build a basketball-themed cake fit for the pros, but when their event is canceled, they plan a cake party on the fly in a new episode of Duff Takes the Cake. -

Doña Ana County ARTS & Branch

Local news and entertainment since 1969 WomenW of DistinctionD available 2020 inside HEALTHY HORIZONS COMMUNITY NEWSLETTER FRIDAY, DECEMBER 27, 2019 I Volume 51, Number 52 I lascrucesbulletin.comco INSIDE NEWS Still Bloomin Brown to ride in Rose Bowl page 10 Las Crucen Clayton Flow- ers was feted Dec. 17 at a reception hosted by the NAACP Doña Ana County ARTS & Branch. Flowers, a former ENTERTAINMENT Tuskegee Airman, turned 104 on Christmas Day. The Tuskegee Airmen were the first black mili- tary aviators in the U.S. Army Air Corps, a precur- sor to the U.S. Air Force. Border Artists honor founding BULLETIN PHOTO BY member RICHARD COLTHARP page 26 This holiday season reminds us that we are fortunate to be a part of this great community. We wish you and your Happy Holidays loved ones a safe, healthy and happy holiday season. and A HEALTHY NEW YEAR MMCLC.org 2 | FRIDAY, DECEMBER 27, 2019 NEWS LAS CRUCES BULLETIN Content brought to you by: Doña Ana County ‘Your Partner in Progress’ Agreement showcases mul-stakeholder collaboraon It is just the type of project that the U.S. Army employees to find resources and money that would Xochitl Torres Small, New Mexico State Sen. Jeff Corps of Engineers’ staff enjoys working on, said Lt. bring that solution to life. Steinborn, State Reps. Rodolpho “Rudy” S. Martinez, Col., U.S. Army District Commander Larry D. “This was really made possible through a collabora- and Nathan P. Small. Caswell, Jr. A dam to help prevent flooding in the Vil- tive effort,” said Dist.