Woman's Image in Authoritative Mormon Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARY JANE WOODGER 275 E Joseph Smith Building Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 84602 (801) 422-9029 Work

MARY JANE WOODGER 275 E Joseph Smith Building Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 84602 (801) 422-9029 Work PROFESSIONAL TRACK 2009-present Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 2003-2009 Associate Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 1997-2003 Assistant Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 1994-99 Faculty, Department of Ancient Scripture, BYU Salt Lake Center 1980-97 Department Chair of Home Economics, Jordan School District, Midvale Middle School, Sandy, Utah EDUCATION 1997 Ed.D. Brigham Young University, Educational Leadership, Minor: Church History and Doctrine 1992 M.Ed. Utah State University, Secondary Education, Emphasis: American History 1980 B.S. Brigham Young University, Home Economics Education HONORS 2012 The Harvey B. Black and Susan Easton Black Outstanding Publication Award: Presented in recognition of an outstanding published scholarly article or academic book in Church history, doctrine or related areas for Against the Odds: The Life of George Albert Smith (Covenant Communications, Inc., 2011). 2012 Alice Louise Reynolds Women-in-Scholarship Lecture 2006 Brigham Young University Faculty Women’s Association Teaching Award 2005 Utah State Historical Society’s Best Article Award “Non Utah Historical Quarterly,” for “David O. McKay’s Progressive Educational Ideas and Practices, 1899-1922.” 1998 Kappa Omicron Nu, Alpha Tau Chapter Award of Excellence for research on David O. McKay 1997 The Crystal Communicator Award of Excellence (An International Competition honoring excellence in print media, 2,900 entries in 1997. Two hundred recipients awarded.) Research consultant for David O. McKay: Prophet and Educator Video 1994 Midvale Middle School Applied Science Teacher of the Year 1987 Jordan School District Vocational Teacher of the Year PUBLICATIONS Authored Books (18) Casey Griffiths and Mary Jane Woodger, 50 Relics of the Restoration (Springville, Utah: Cedar Fort Press, 2020). -

MINERVA TEICHERT's JESUS at the HOME of MARY and MARTHA: REIMAGINING an ORDINARY HEROINE by Tina M. Delis a Thesis Project

MINERVA TEICHERT’S JESUS AT THE HOME OF MARY AND MARTHA: REIMAGINING AN ORDINARY HEROINE by Tina M. Delis A Thesis Project Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Art History Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Department Chairperson ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Spring Semester 2015 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Minerva Teichert’s Jesus at the Home of Mary and Martha: Reimagining an Ordinary Heroine A Thesis Project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University by Tina M. Delis Bachelor of Arts George Mason University, 1987 Director: Ellen Wiley Todd, Professor Department of Art History Spring Semester 2015 George Mason University Fairfax, VA This work is licensed under a creative commons attribution-noderivs 3.0 unported license. ii DEDICATION For Jim, who teaches me every day that anything is possible if you have the courage to take the first step. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the many friends, relatives, and supporters who have made this happen. To begin with, Dr. Ellen Wiley Todd and Dr. Angela Ho who with great patience, spent many hours reading and editing several drafts to ensure I composed something I would personally be proud of. In addition, the faculty in the Art History program whose courses contributed to small building blocks for the overall project. Dr. Marian Wardle for sharing insights about her grandmother. Lastly, to my family who supported me in more ways than I could ever list. -

Worth Their Salt, Too

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@USU Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2000 Worth Their Salt, Too Colleen Whitley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Whitley, C. (2000). Worth their salt, too: More notable but often unnoted women of Utah. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Worth Their Salt, Too More Notable but Often Unnoted Women of Utah WORTH THEIR SALT, TOO More Notable but Often Unnoted Women of Utah Edited by Colleen Whitley UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Logan, Utah 2000 Copyright © 2000 Utah State University Press “Marion Davis Clegg: The Lady of the Lakes” copyright © 2000 Carol C. Johnson All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322-7800 All royalties from the sale of this book will be donated to support the Exhibits office of the Utah State Historical Society. Cover photos: Marion Davis Clegg, courtesy of Photosynthesis; Verla Gean FarmanFarmaian, courtesy of Gean FarmanFarmaian; Ora Bailey Harding, courtesy of Lurean S. Harding; Alberta Henry, courtesy of the Deseret News; Esther Peterson, courtesy of Paul A. Allred; Virginia Sorensen, courtesy of Mary Bradford Typography by WolfPack Printed in Canada Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Worth their salt, too : more notable but often unnoted women of Utah / edited by Colleen Whitley. -

RSC Style Guide

Religious Studies Center Style Guide, 1 October 2018 Authors who submit manuscripts for potential publication should generally follow the guidelines in The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2017) and Style Guide for Editors and Writers, 5th ed. (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2013). This style guide summarizes the main principles in the other style guides and lists a few exceptions to their guidelines. Formatting 1. Use double-spacing throughout the manuscript and the endnotes. Use one-inch margins, and insert page numbers at the bottom of the page. Use a Times New Roman 12-point font for both the body of the manuscript and the notes. Use only one space after periods. 2. If you have images, add captions and courtesy lines (such as courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City) to the Word file. However, do not insert images in the Word files; submit them separately. Images should be 300 dpi or better (TIFF or JPG files). File names and captions should match (Fig. 1.1 = chapter 1, figure 1). Headings 3. Update: Include headings to break up the text. First-Level Headings First-level headings should be flush left and bolded, as in the example above. Capitalize internal words except for articles (a, an, and the), conjunctions (and, but, or, for, so, and yet), prepositions, and the word to in infinitive phrases. Second-Level Headings Second-level headings should be flush left and italicized. Capitalize like first-level headings. Third-level headings. Third-level headings should be italicized, followed by a period, and run in to the text; capitalization should be handled sentence-style (capitalize the first word and proper nouns). -

Session Slides

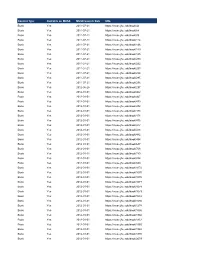

Content Type Available on MUSE MUSE Launch Date URL Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/42 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/68 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/89 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/114 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/146 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/149 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/185 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/280 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/292 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/293 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/294 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/295 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/296 Book Yes 2012-06-26 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/297 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/462 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/467 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/470 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/472 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/473 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/474 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/475 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/477 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/478 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/482 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/494 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/687 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/708 Book Yes 2012-01-11 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/780 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/834 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/840 Book Yes 2012-01-01 -

Relief Society's Golden Years: the Magazine

Relief Society's Golden Years: The Magazine Jean Anne Waterstradt UJ MOTHER WAS AN ENTHUSIASTIC, devoted member of the Relief So- ciety—the old Relief Society, the pre-block-meeting-schedule, pre-Correla- tion Relief Society. She belonged to a Relief Society that LDS women chose to join by paying a small annual membership fee; that had its own meeting day and its own budget; that organized bazaars; that sponsored Singing Mothers choruses; that published its own songbook; that held its own conference each autumn in the Salt Lake Tabernacle; that built its own headquarters in Salt Lake City on the southeast corner of Main and North Temple Streets; that published its own magazine. For my mother, who, I think, was a typical member, the Magazine was indispensable because it was a tangible reminder in her home of all that Re- lief Society offered and accomplished. And, this magazine had an influence beyond its Relief Society constituency. For example, my teacher, friend, and colleague Ralph Britsch has written that when he was a youngster, the women whose names appeared on the masthead of the Magazine and as au- thors of various features "ranked only a little lower in my mind than the General Authorities." The context for his remark was a memoir honoring Alice Louise Reynolds, a BYU professor, a member of the Relief Society General Board, and an associate editor and then editor of the Maga- JEAN ANNE WATERSTRADT is professor emerita of English, Brigham Young University. Currently residing in Ogden, Utah, she is happily associated with the Friends of the Stewart Library at Weber State University as well as with the Ogden School Foundation. -

May 2005 New

THE MAY 2005 SPECIAL ISSUE: THE TIMES AND SEASONS OF JOSEPH SMITH The New Era Magazine oseph Volume 35, Number 5 oseph May 2005 Smith . Official monthly publication J Jhas done for youth of The Church of Jesus Christ more, save of Latter-day Saints Jesus only, for The New Era can be found the salvation in the Gospel Library at www.lds.org. of men in this world, than Editorial Offices: any other man New Era any other man 50 E. North Temple St. that ever lived Rm. 2420 Salt Lake City, UT in it” (D&C 84150-3220, USA 135:3). E-mail address: cur-editorial-newera In this @ldschurch.org special issue, Please e-mail or send stories, articles, photos, poems, and visit the ideas to the address above. Unsolicited material is wel- places where come. For return, include a the Prophet self-addressed, stamped the Prophet envelope. Joseph Smith To Subscribe: lived, and feel By phone: Call 1-800-537- 5971 to order using Visa, the spirit of MasterCard, Discover Card, or American Express. Online: all he Go to www.ldscatalog.com. By mail: Send $8 U.S. accomplished check or money order to Distribution Services, as the first P.O. Box 26368, Salt Lake City, UT President of 84126-0368, USA. The Church of To change address: Jesus Christ of Send old and new address information to Distribution Latter-day Services at the address above. Please allow 60 days Saints. for changes to take effect. Cover: Young Joseph Smith begins the great work of the Restoration. -

September 2011 Liahona

UNTIL WE MEET AGAIN eight weeks he returned to Heavenly TEMPLE BLESSINGS Father. As I held him for the last time, NOW AND I recognized yet another wonderful blessing of the temple: our son had ETERNALLY been born in the covenant and could be ours forever. Eighteen months after the passing of our son, we received a phone call from By Stacy Vickery LDS Family Services saying that a young remember seeing pictures of the temple woman had chosen to place her baby from the time I was very small. Though too with us. Knowing that we could not I young to understand the blessings of the have more biological children, we could temple, I knew I wanted to go there someday. not have been more excited. In Young Women, I started to understand the When our little girl was six months blessings that would come from the temple. old, we finalized her adoption and At that time my family was less active, and I My under- took her to the temple to be sealed to us. Four prayed each day that we could be sealed as an standing years after our little girl became part of our eternal family. of temple family, another young woman chose us to be In the fall of 1993, two weeks before I turned blessings the parents of a sweet little boy. Again we had 18, my family did go to the temple. I remember has grown the blessing of taking a six-month-old to the the feeling I had in the Provo Utah Temple, temple. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 20, No. 1, 1994

Journal of Mormon History Volume 20 Issue 1 Article 1 1994 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 20, No. 1, 1994 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1994) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 20, No. 1, 1994," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 20 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol20/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 20, No. 1, 1994 Table of Contents LETTERS vi ARTICLES PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS • --Positivism or Subjectivism? Some Reflections on a Mormon Historical Dilemma Marvin S. Hill, 1 TANNER LECTURE • --Mormon and Methodist: Popular Religion in the Crucible of the Free Market Nathan O. Hatch, 24 • --The Windows of Heaven Revisited: The 1899 Tithing Reformation E. Jay Bell, 45 • --Plurality, Patriarchy, and the Priestess: Zina D. H. Young's Nauvoo Marriages Martha Sonntag Bradley and Mary Brown Firmage Woodward, 84 • --Lords of Creation: Polygamy, the Abrahamic Household, and Mormon Patriarchy B. Cannon Hardy, 119 REVIEWS 153 --The Story of the Latter-day Saints by James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard Richard E. Bennett --Hero or Traitor: A Biographical Story of Charles Wesley Wandell by Marjorie Newton Richard L. Saunders --Mormon Redress Petition: Documents of the 1833-1838 Missouri Conflict edited by Clark V. Johnson Stephen C. -

Roger Terry, “Authority and Priesthood in the LDS Church, Part 1: Definitions and Development,”

ARTICLES AND ESSAYS AUTHORITY AND PRIESTHOOD IN THE LDS CHURCH, PART 1: DEFINITIONS AND DEVELOPMENT Roger Terry The issue of authority in Mormonism became painfully public with the rise of the Ordain Women movement. The Church can attempt to blame (and discipline) certain individuals, but this development is a lot larger than any one person or group of people. The status of women in the Church was basically a time bomb ticking down to zero. With the strides toward equality American society has taken over the past sev- eral decades, it was really just a matter of time before the widening gap between social circumstances in general and conditions in Mormondom became too large to ignore. When the bomb finally exploded, the Church scrambled to give credible explanations, but most of these responses have felt inadequate at best. The result is a good deal of genuine pain and a host of very valid questions that have proven virtually impossible to answer satisfactorily. At least in my mind, this unfolding predicament has raised certain important questions about what priesthood really is and how it cor- responds to the larger idea of authority. What is this thing that women are denied? What is this thing that, for over a century, faithful black LDS men were denied? Would clarifying or fine-tuning our definition—or even better understanding the history of how our current definition developed—perhaps change the way we regard priesthood, the way we practice it, the way we bestow it, or refuse to bestow it? The odd sense I have about priesthood, after a good deal of study and pondering, is 1 2 Dialogue, Spring 2018 that most of us don’t really have a clear idea of what it is and how it has evolved over the years. -

A Study of the History of the Office of High Priest

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2006-07-18 A Study of the History of the Office of High Priest John D. Lawson Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History of Christianity Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Lawson, John D., "A Study of the History of the Office of High Priest" (2006). Theses and Dissertations. 749. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/749 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A STUDY OF THE HISTORY OF THE OFFICE OF HIGH PRIEST by John Lawson A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Religious Education Brigham Young University July 2006 Copyright © 2006 John D. Lawson All Rights Reserved ii BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL Of a thesis submitted by John D. Lawson This thesis has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and has been found to be satisfactory. ___________________________ ____________________________________ Date Craig J. Ostler, Chair ___________________________ ____________________________________ Date Joseph F. McConkie ___________________________ ____________________________________ Date Guy L. Dorius iii BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY As chair of the candidate’s graduate committee, I have read the thesis of John D. Lawson in its final form and have found that (1) its format, citations, and bibliographical style are consistent and acceptable and fulfill university and department style requirements; (2) its illustrative materials including figures, tables, and charts are in place; and (3) the final manuscript is satisfactory to the graduate committee and is ready for submission to the university library. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO the New and Everlasting

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The New and Everlasting Order of Marriage: The Introduction and Implementation of Mormon Polygamy: 1830-1856 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Merina Smith Committee in charge: Professor Rebecca Plant, Chair Professor Claudia Bushman Professor John Evans Professor Mark Hanna Professor Christine Hunefeldt Professor Rachel Klein 2011 The Dissertation of Merina Smith is approved, and is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ Chair University of San Diego 2011 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………………… iii Table of Contents………………………………………………………………….. iv Vita………………………………………………………………………………… v Abstract……………………………………………………………………………. vi Introduction ..……………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter One: ………………………………………………………………………. 28 Mormon Millenarian Expectations: 1830-1841 The Restoration of All Things and the Resacralization of Marriage Chapter Two: ………………………………………………………………………. 84 Nauvoo Secrets and the Rise of a Mormon Salvation Narrative, 1841-42 Chapter Three: ……………………………………………………………………... 148 Scandal and Resistance, 1842 Chapter Four: