Progress Liam Byrne Q7.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Progressive Now?

Who’s progressive now? Greg Clark MP Jeremy Hunt MP Who’s progressive now? Greg Clark MP Jeremy Hunt MP 1 Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank Peter Franklin, Joanna Garner, Adam Smith and David O’Leary for their help in preparing this booklet. 2 Chapter 1: Progressive politics Introduction – whatever happened to the ‘Progressive Consensus’? During the last five years, Gordon Brown and his retinue of younger advisers have been on a quest – to define a political project that will in turn define his premiership. It has proved to be an arid task. Smith Institute seminars in 11 Downing Street have cast around in vain for a purpose that could be described coherently, let alone one that could be said to define the Brown vision. In the end, the task has been abandoned. Three events in the space of three weeks signalled the emptiness of Labour’s intellectual larder. First - the new Prime Minister’s barren conference speech in Brighton in September revealed that the preceding groundwork of seminars, symposia and speeches had offered up nothing usable. Next, the cancellation of the expected election, which was explained as allowing the Prime Minister another two years to set out his vision, was in fact a recognition that there was no vision to set out that would survive the scrutiny of an election campaign. Then came the intellectual surrender of the following week, in which Conservative reforms to inheritance tax set the agenda for what was, in effect, the first Budget of the Brown premiership. With no new idea that did not come from the Opposition, Alistair Darling’s statement signalled the end of the new regime’s ambition to forge an agenda of its own. -

The Labour Party Is More Than the Shadow Cabinet, and Corbyn Must Learn to Engage with It

The Labour Party is more than the shadow cabinet, and Corbyn must learn to engage with it blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/the-labour-party-is-more-than-the-shadow-cabinet/ 1/11/2016 The three-day reshuffle of the shadow cabinet might have helped Jeremy Corbyn stamp his mark on the party but he needs to do more to ensure his leadership lasts, writes Eunice Goes. She explains the Labour leader must engage with all groups that have historically made up the party, while his rhetoric should focus more on policies that resonate with the public. Doing so will require a stronger vision of what he means by ‘new politics’ and, crucially, a better communications strategy. By Westminster standards Labour’s shadow cabinet reshuffle was ‘shambolic’ and had the key ingredients of a ‘pantomime’. At least, it was in those terms that it was described by a large number of Labour politicians and Westminster watchers. It certainly wasn’t slick, or edifying. Taking the best of a week to complete a modest shadow cabinet reshuffle was revealing of the limited authority the leader Jeremy Corbyn has over the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP). Against the wishes of the Labour leader, the Shadow Foreign Secretary Hilary Benn and the Shadow Chief Whip Rosie Winterton kept their posts. However, Corbyn was able to assert his authority in other ways. He moved the pro-Trident Maria Eagle from Defence and appointed the anti-Trident Emily Thornberry to the post. He also imposed some ground rules on Hillary Benn and got rid of Michael Dugher and Pat McFadden on the grounds of disloyalty. -

Beat the Credit Crunch with Alvin’S Stardust

learthe ni ng rep » Winter 2010 Viva the revolution! Festival promotes informal learning Welcome to No 10 … Apprentices meet their own minister Teaching the teachers Unions help combat bad behaviour Quick Reads exclusive Beat the credit crunch with Alvin’s stardust www.unionlearn.org.uk » Comment A celebration of 49 apprenticeships Last month unionlearn was at 10 Downing Street to celebrate apprenticeships. A packed event saw apprentices from a range of backgrounds and from a range of unions mixing with guests and ministers. The enjoyable and inspiring evening showed off the benefits of apprenticeships and brought together some exceptional young people. Three of the apprentices (Adam Matthews from the PFA and Cardiff City FC; Leanne Talent from UNISON and Merseytravel; Richard Sagar from Unite and Eden Electrics) addressed the audience and impressed everyone there. A big thank to them for their professionalism and eloquence when speaking on the day. 10 14 A thank you too to ministers Kevin Brennan, Pat McFadden and Iain Wright for joining us, as well as Children’s Secretary Ed Balls and 16 Business Secretary Lord Mandelson. A strong commitment to support and expand apprentices was given by Gordon Brown, which was warmly welcomed by all those there. In this issue of The Learning Rep , you will find a full report of the Downing Street event with some great photographs of the apprentices. 18 28 We’ve decided to make this issue an apprentices special and it includes interviews with Richard, Leanne and Adam who spoke at the Downing Contents: Street event as well as an interview with Kevin 3 24 Brennan, the apprentices minister. -

Z675928x Margaret Hodge Mp 06/10/2011 Z9080283 Lorely

Z675928X MARGARET HODGE MP 06/10/2011 Z9080283 LORELY BURT MP 08/10/2011 Z5702798 PAUL FARRELLY MP 09/10/2011 Z5651644 NORMAN LAMB 09/10/2011 Z236177X ROBERT HALFON MP 11/10/2011 Z2326282 MARCUS JONES MP 11/10/2011 Z2409343 CHARLOTTE LESLIE 12/10/2011 Z2415104 CATHERINE MCKINNELL 14/10/2011 Z2416602 STEPHEN MOSLEY 18/10/2011 Z5957328 JOAN RUDDOCK MP 18/10/2011 Z2375838 ROBIN WALKER MP 19/10/2011 Z1907445 ANNE MCINTOSH MP 20/10/2011 Z2408027 IAN LAVERY MP 21/10/2011 Z1951398 ROGER WILLIAMS 21/10/2011 Z7209413 ALISTAIR CARMICHAEL 24/10/2011 Z2423448 NIGEL MILLS MP 24/10/2011 Z2423360 BEN GUMMER MP 25/10/2011 Z2423633 MIKE WEATHERLEY MP 25/10/2011 Z5092044 GERAINT DAVIES MP 26/10/2011 Z2425526 KARL TURNER MP 27/10/2011 Z242877X DAVID MORRIS MP 28/10/2011 Z2414680 JAMES MORRIS MP 28/10/2011 Z2428399 PHILLIP LEE MP 31/10/2011 Z2429528 IAN MEARNS MP 31/10/2011 Z2329673 DR EILIDH WHITEFORD MP 31/10/2011 Z9252691 MADELEINE MOON MP 01/11/2011 Z2431014 GAVIN WILLIAMSON MP 01/11/2011 Z2414601 DAVID MOWAT MP 02/11/2011 Z2384782 CHRISTOPHER LESLIE MP 04/11/2011 Z7322798 ANDREW SLAUGHTER 05/11/2011 Z9265248 IAN AUSTIN MP 08/11/2011 Z2424608 AMBER RUDD MP 09/11/2011 Z241465X SIMON KIRBY MP 10/11/2011 Z2422243 PAUL MAYNARD MP 10/11/2011 Z2261940 TESSA MUNT MP 10/11/2011 Z5928278 VERNON RODNEY COAKER MP 11/11/2011 Z5402015 STEPHEN TIMMS MP 11/11/2011 Z1889879 BRIAN BINLEY MP 12/11/2011 Z5564713 ANDY BURNHAM MP 12/11/2011 Z4665783 EDWARD GARNIER QC MP 12/11/2011 Z907501X DANIEL KAWCZYNSKI MP 12/11/2011 Z728149X JOHN ROBERTSON MP 12/11/2011 Z5611939 CHRIS -

UKIP-Wales-Manifesto-2021.Pdf

UKIP Wales Senedd Manifesto 2021 2021 Senedd Election www.ukip.wales Page 1 CONTENTS Page Topic 1 Introduction 2 Devolution 6 Immigration 8 Health & Social Care 14 Education 18 Transport & Economic Development 20 Environment, Energy & Rural Affairs 23 Welsh Language 25 The Family 27 Veterans’ Issues 29 Culture & Communities 31 Contact Details www.ukip.wales INTRODUCTION Neil Hamilton MS Leader, UKIP Wales Today, devolution is a one-way revenue amounting to only 25% process. Despite Government with the funding gap being filled of Wales Acts in 1998, 2006, by the English taxpayer. 2014 and 2017, the train keeps on moving in only one direction The time has come to stop - towards independence. The this runaway train to the Welsh Government always disintegration of the UK and demands more power – just institutionalised poverty and like the Euro-federalists of decline for Wales. the European Commission. The Welsh Government now Only UKIP has a full manifesto wants the devolution of justice of policies to put Wales back on and to remove limits on Welsh the UK political map, reverse Government borrowing. institutional economic decline, transfer power in health and Fearful of failing to win an education from Cardiff Bay outright majority in these and directly to the people who elections, First Minister use these vital services, to Drakeford has been cosying up to support strict controls on mass “Only UKIP has Plaid Cymru to get their support immigration and end bogus for continuing the permanent asylum-seeking, and defend a full manifesto Labour Government either as full British history and culture from coalition partners or through a leftist, anti-British attacks. -

Sessional Diary 2015–16

HOUSE OF COMMONS SESSIONAL DIARY 2015–16 18 May 2015 to 12 May 2016 Prepared in the Journal Office of the House of Commons INTRODUCTION 1. This diary records the business on which the House spent its time in Session 2015–16, analysed into categories, and similar information for sittings in Westminster Hall. It is intended mainly to provide information in response to statistical inquiries, and in using it the following points should be borne in mind: (a) The diary does not include business which took little or no time, such as presentations of bills, unopposed private business, and motions agreed to without debate or division. (b) Divisions are normally included with the business to which they relate. (c) Timings are taken from the Official Report, using the printed times where available, and otherwise taking a column of debate to last three minutes. Daily prayers are assumed to last a standard five minutes, unless stated otherwise (and are not itemised in the analysis). (d) Periods of suspension are included in the total sitting time, and are listed in section 14j of the analysis (Miscellaneous). However, the 2½-hour suspension from 11.30 to 14.00 in Westminster Hall on most Tuesdays and Wednesdays (introduced on 1 January 2003) is shown in brackets in the “Duration” column and is left out of the totals. Other suspensions in Westminster Hall are included in the totals and in the analysis under section 7. (e) The times in the column headed “After appointed time” refer to business taken after the time appointed as the “moment of interruption”. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

One Nation: Power, Hope, Community

one nation power hope community power hope community Ed Miliband has set out his vision of One Nation: a country where everyone has a stake, prosperity is fairly shared, and we make a common life together. A group of Labour MPs, elected in 2010 and after, describe what this politics of national renewal means to them. It begins in the everyday life of work, family and local place. It is about the importance of having a sense of belonging and community, and sharing power and responsibility with people. It means reforming the state and the market in order to rebuild the economy, share power hope community prosperity, and end the living standards crisis. And it means doing politics in a different way: bottom up not top down, organising not managing. A new generation is changing Labour to change the country. Edited by Owen Smith and Rachael Reeves Contributors: Shabana Mahmood Rushanara Ali Catherine McKinnell Kate Green Gloria De Piero Lilian Greenwood Steve Reed Tristram Hunt Rachel Reeves Dan Jarvis Owen Smith Edited by Owen Smith and Rachel Reeves 9 781909 831001 1 ONE NATION power hope community Edited by Owen Smith & Rachel Reeves London 2013 3 First published 2013 Collection © the editors 2013 Individual articles © the author The authors have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1998 to be identified as authors of this work. All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, electrical, chemical, mechanical, optical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. -

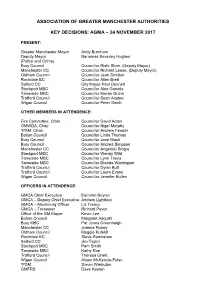

AGMA Decisions Agreed 24 November 2017 FINAL, Item 3F PDF

ASSOCIATION OF GREATER MANCHESTER AUTHORITIES KEY DECISIONS: AGMA – 24 NOVEMBER 2017 PRESENT: Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham Deputy Mayor Baroness Beverley Hughes (Police and Crime) Bury Council Councillor Rishi Shori, (Deputy Mayor) Manchester CC Councillor Richard Leese, (Deputy Mayor) Oldham Council Councillor Jean Stretton Rochdale BC Councillor Allen Brett Salford CC City Mayor Paul Dennett Stockport MBC Councillor Alex Ganotis Tameside MBC Councillor Kieran Quinn Trafford Council Councillor Sean Anstee Wigan Council Councillor Peter Smith OTHER MEMBERS IN ATTENDENCE: Fire Committee, Chair Councillor David Acton GMWDA, Chair Councillor Nigel Murphy TfGM, Chair, Councillor Andrew Fender Bolton Council Councillor Linda Thomas Bury Council Councillor Jane Black Bury Council Councillor Andrea Simpson Manchester CC Councillor Angelicki Stogia Stockport MBC Councillor Wendy Wild Tameside MBC Councillor Lynn Travis Tameside MBC Councillor Brenda Warrington Trafford Council Councillor Dylan Butt Trafford Council Councillor Laura Evans Wigan Council Councillor Jennifer Bullen OFFICERS IN ATTENDENCE: GMCA Chief Executive Eamonn Boylan GMCA – Deputy Chief Executive Andrew Lightfoot GMCA – Monitoring Officer Liz Treacy GMCA – Treasurer Richard Paver Office of the GM Mayor Kevin Lee Bolton Council Margaret Asquith Bury MBC Pat Jones Greenhalgh Manchester CC Joanne Roney Oldham Council Maggie Kufeldt Rochdale BC Steve Rumbelow Salford CC Jim Taylor Stockport MBC Pam Smith Tameside MBC Kathy Roe Trafford Council Theresa Grant Wigan Council Alison McKenzie-Folan TfGM Simon Warbuton GMFRS Dave Keelan Manchester Growth Co Mark Hughes GMCA Julie Connor GMCA Lindsay Dunn GMCA Simon Nokes GMCA Emma Stonier GMCA Sylvia Welsh APOLOGIES: Bolton Council Councillor Cliff Morris Oldham Council Carolyn Wilkins Rochdale BC Councillor Richard Farnell Tameside MBC Steven Pleasant Wigan Council Donna Hall GMP Ian Hopkins GMHSC Partnership Jon Rouse TfGM Jon Lamonte Agenda Item No. -

General Election Results, 29 MARCH 2001 1 May 1997

RESEARCH PAPER 01/38 General Election results, 29 MARCH 2001 1 May 1997 This paper summarises the results of the 1997 General Election. It is a re-issue of Research Paper 97/49 but contains validated voting figures and also additional tables showing results by constituency. Full results of by-elections in this Parliament are available in Research Paper 01/36 By-elections since the 1997 General Election while more summarised results of General Elections since 1945 and other elections in the UK since 1997 are available in Research Paper 01/37 UK Election Statistics: 1945-2000. Bryn Morgan SOCIAL & GENERAL STATISTICS SECTION HOUSE OF COMMONS LIBRARY Recent Library Research Papers include: 01/23 The Transplant of Human Organs Bill [Bill 17 of 2000-2001] 14.03.01 01/24 Direct taxes: rates & allowances 2001-02 14.03.01 01/25 Unemployment by constituency, February 2001 14.03.01 01/26 The Regulatory Reform Bill: Background to Red tape issues 14.03.01 01/27 The Regulatory Reform Bill: order-making power & parliamentary aspects 14.03.01 01/28 Police Service Strength: England & Wales (31 March 1977 to 30 September 2000) 16.03.01 01/29 The Special Needs and Disability Bill [HL] [Bill 55 of 2000-2001] 16.03.01 01/30 Election of a Commons Speaker (2nd Edition) 19.03.01 01/31 The National Lottery (Amendment) Bill [Bill 15 of 2000-2001] 22.03.01 01/32 The Social Security Fraud Bill [Bill 60 of 2000-2001] 21.03.01 01/33 The Adoption and Children Bill [Bill 66 of 2000-2001] 23.03.01 01/34 The Private Security Industry Bill [Bill 67 of 2000-2001] 26.03.01 01/35 Foot and Mouth Disease 27.03.01 01/36 By-elections 1997-2000 28.03.01 01/37 UK election statistics 1945-2000 29.03.01 Research Papers are available as PDF files: • to members of the general public on the Parliamentary web site, URL: http://www.parliament.uk • within Parliament to users of the Parliamentary Intranet, URL: http://hcl1.hclibrary.parliament.uk Library Research Papers are compiled for the benefit of Members of Parliament and their personal staff. -

Let's Not Go Back to 70S Primary Education Wikio

This site uses cookies to help deliver services. By using this site, you agree to the use of cookies. Learn more Got it Conor's Commentary A blog about politics, education, Ireland, culture and travel. I am Conor Ryan, Dublin-born former adviser to Tony Blair and David Blunkett on education. Views expressed on this blog are written in a personal capacity. Friday, 20 February 2009 SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE UPDATES Let's not go back to 70s primary education Wikio Despite the Today programme's insistence on the term, "independent" is certainly not an apt Contact me description of today's report from the self-styled 'largest' review of primary education in 40 years. It You can email me here. is another deeply ideological strike against standards and effective teaching of the 3Rs in our primary schools. Many of its contributors oppose the very idea of school 'standards' and have an ideological opposition to external testing. They have been permanent critics of the changes of recent decades. And it is only in that light that the review's conclusions can be understood. Of course, there is no conflict between teaching literacy and numeracy, and the other subjects within the primary curriculum. And the best schools do indeed show how doing them all well provides a good and rounded education. Presenting this as the point of difference is a diversionary Aunt Sally. However, there is a very real conflict between recognising the need to single literacy and numeracy out for extra time over the other subjects as with the dedicated literacy and numeracy lessons, and making them just another aspect of primary schooling that pupils may or may not pick up along the way. -

Ministerial Reshuffle – 5 June 2009 8 June 2009

Ministerial Reshuffle – 5 June 2009 8 June 2009 This note provides details of the Cabinet and Ministerial reshuffle carried out by the Prime Minister on 5 June following the resignation of a number of Cabinet members and other Ministers over the previous few days. In the new Cabinet, John Denham succeeds Hazel Blears as Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government and John Healey becomes Housing Minister – attending Cabinet - following Margaret Beckett’s departure. Other key Cabinet positions with responsibility for issues affecting housing remain largely unchanged. Alistair Darling stays as Chancellor of the Exchequer and Lord Mandelson at Business with increased responsibilities, while Ed Miliband continues at the Department for Energy and Climate Change and Hilary Benn at Defra. Yvette Cooper has, however, moved to become the new Secretary of State for Work and Pensions with Liam Byrne becoming Chief Secretary to the Treasury. The Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills has been merged with BERR to create a new Department for Business, Innovation and Skills under Lord Mandelson. As an existing CLG Minister, John Healey will be familiar with a number of the issues affecting the industry. He has been involved with last year’s Planning Act, including discussions on the Community Infrastructure Levy, and changes to future arrangements for the adoption of Regional Spatial Strategies. HBF will be seeking an early meeting with the new Housing Minister. A full list of the new Cabinet and other changes is set out below. There may yet be further changes in junior ministerial positions and we will let you know of any that bear on matters of interest to the industry.