Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rudyard Kipling's Techniques

Rudyard Kipling's Techniques The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Friedman, Robert Louis. 2016. Rudyard Kipling's Techniques. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33797390 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ! Rudyard Kipling’s Techniques: Their Influence on a Novel of Stories An Introductory Essay and an Original Novel, Answers Lead Us Nowhere Robert Louis Friedman A Thesis in the Field of Literature and Creative Writing for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2016 ! ! Copyright 2016 Robert Louis Friedman ! ! Abstract This thesis investigates the techniques of Rudyard Kipling and his influence on my “novel of short stories”. How did Kipling advance the short story form over a half-century of experimentation? How did his approaches enliven the reader’s experience to such a degree that his greatest works have remained in print? Beginning in 1888 with Plain Tales From the Hills, Kipling utilized three innovative techniques: the accretion of unrelated stories into the substance of a novel; the use of tales with their fantastical dreamlike appeal (as opposed to standard fictional styles of realism or naturalism) to both salute and satirize characters in adult fiction; and the swift deployment of back story to enhance both the interwoven nature and tale-like feel of the collection. -

On to the Rescue

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES ON TO THE RESCUE : Willie had raised himself, and was gazing wonderingly on the speaker." p. 43. On to the Rescue. A TALE OF THE INDIAN MUTINY, GORDON STABLES, M.D., C.M. (Surgeon Royal Navy), AtiTHOH OF "FACING FEARFUL ODDS;" " "FOB ENGLAND, HOME, AKD BEAUTT J "HEARTS OF OAK J" 1 Stars and moon and sun may wax and wane, subside and rise, Age on age as flake on flake of showering snows be shed : Not till earth be sunless, not till death strike blind the skies, May the deathless love that waits on deathless deeds be dead. NEW EDITION. LONDON: JOHN F. SHAW AND CO., 48, PATERNOSTER ROW, B.C. UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME. TWO SAILOR LADS .. .. By DR. GORDON STABLES. IN SEARCH OF FORTUNE .. DR. GORDON STABLES. FOR ENGLAND, HOME, AND BEAUTY DR. GORDON STABLES. HEARTS OF OAK DR. GORDON STABLES. OLD ENGLAND ON THE SEA DR. GORDON STABLES. UNCLE TOM'S CABIN H. B. STOWE. GRIMM'S FAIRY TALES BROS. GRIMM. EDGAR NELTHORPE ANDREW REED. WINNING AN EMPIRE G. STEBBING. DOROTHY'S STORY .. L. T. MKADE. A TRUE GENTLEWOMAN EMMA MARSHALL. BEL-MARJORY L. T. MEADE. LOVEDAY'S HISTORY L. E. GUERNSEY. FOR HONOUR NOT HONOURS DR. GORDON STABLES. IDA VANE .. ANDREW REED. GRAHAM'S VICTORY G. STEBBING. THE END CROWNS ALL EMMA MARSHALL. THE WIDE, WIDE WORLD .. E. WBTHEKBLL. HER HUSBAND'S HOME E. EVERETT-GREEN. NIGEL BROWNING .. AGNES GIBERNE. THE FOSTER-SISTERS L. E. GUERNSEY. THE CORAL ISLAND R. M. BALLANTYNE. WINNING THE GOLDEN SPURS H. -

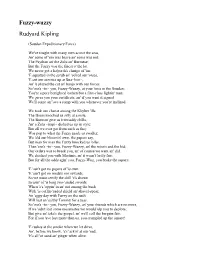

Fuzzy-Wuzzy Rudyard Kipling

Fuzzy-wuzzy Rudyard Kipling (Soudan Expeditionary Force) We've fought with many men acrost the seas, An' some of 'em was brave an' some was not: The Paythan an' the Zulu an' Burmese; But the Fuzzy was the finest o' the lot. We never got a ha'porth's change of 'im: 'E squatted in the scrub an' 'ocked our 'orses, 'E cut our sentries up at Sua~kim~, An' 'e played the cat an' banjo with our forces. So 'ere's ~to~ you, Fuzzy-Wuzzy, at your 'ome in the Soudan; You're a pore benighted 'eathen but a first-class fightin' man; We gives you your certificate, an' if you want it signed We'll come an' 'ave a romp with you whenever you're inclined. We took our chanst among the Khyber 'ills, The Boers knocked us silly at a mile, The Burman give us Irriwaddy chills, An' a Zulu ~impi~ dished us up in style: But all we ever got from such as they Was pop to what the Fuzzy made us swaller; We 'eld our bloomin' own, the papers say, But man for man the Fuzzy knocked us 'oller. Then 'ere's ~to~ you, Fuzzy-Wuzzy, an' the missis and the kid; Our orders was to break you, an' of course we went an' did. We sloshed you with Martinis, an' it wasn't 'ardly fair; But for all the odds agin' you, Fuzzy-Wuz, you broke the square. 'E 'asn't got no papers of 'is own, 'E 'asn't got no medals nor rewards, So we must certify the skill 'e's shown In usin' of 'is long two-'anded swords: When 'e's 'oppin' in an' out among the bush With 'is coffin-'eaded shield an' shovel-spear, An 'appy day with Fuzzy on the rush Will last an 'ealthy Tommy for a year. -

Your Guide to the Classic Literature Collection

Your Guide to the Classic Literature Collection. Electronic texts for use with Kurzweil 1000 and Kurzweil 3000. Revised March 27, 2017. Your Guide to the Classic Literature Collection – March 22, 2017. © Kurzweil Education, a Cambium Learning Company. All rights reserved. Kurzweil 1000 and Kurzweil 3000 are trademarks of Kurzweil Education, a Cambium Learning Technologies Company. All other trademarks used herein are the properties of their respective owners and are used for identification purposes only. Part Number: 125516. UPC: 634171255169. 11 12 13 14 15 BNG 14 13 12 11 10. Printed in the United States of America. 1 Introduction Introduction Kurzweil Education is pleased to release the Classic Literature Collection. The Classic Literature Collection is a portable library of approximately 1,800 electronic texts, selected from public domain material available from Web sites such as www.gutenberg.net. You can easily access the contents from any of Kurzweil Education products: Kurzweil 1000™, Kurzweil 3000™ for the Apple® Macintosh® and Kurzweil 3000 for Microsoft® Windows®. The collection is also available from the Universal Library for Web License users on K3000+firefly. Some examples of the contents are: • Literary classics by Jane Austen, Geoffrey Chaucer, Joseph Conrad, Charles Dickens, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Hermann Hesse, Henry James, William Shakespeare, George Bernard Shaw, Leo Tolstoy and Oscar Wilde. • Children’s classics by L. Frank Baum, Brothers Grimm, Rudyard Kipling, Jack London, and Mark Twain. • Classic texts from Aristotle and Plato. • Scientific works such as Einstein’s “Relativity: The Special and General Theory.” • Reference materials, including world factbooks, famous speeches, history resources, and United States law. -

Handcrafted in Australia. Since 1969

2019-2020 Handcrafted in Australia. Since 1969. From golden coastlines and endless JACARU HATS sun-baked horizons, dense tropical rainforests and rugged bushland, 4 Kangaroo red deserts and vast sweeping New Premium Range plains, Australia is a country of 8 Western unparalleled uniqueness Our two most iconic hats are now also available in a new premium version - a country like no other. 10 Exotic in addition to our standard models. Available in brown and black. Since its beginning in 1969, the Jacaru brand has reflected this 14 Breeze Australian landscape, its unique lifestyle and the spirit that is 16 Traditional Australia - wild, untameable, strong and courageous. 18 Australian Wool 50 years on, Jacaru has established Ladies itself as one of Australia’s finest 20 accessories brands, selling in over contents 50 countries worldwide. Today, 24 Kid’s we are prouder than ever to be Australian. 26 Summer Lovin’ We believe in Australian made 34 Safety and Workwear products, handcrafted from the finest Australian materials. 37 Wallets & Purses We are proud that our products are 38 Leather Belts designed and made with dedication in the hands of our craftspeople located in Burleigh on the iconic 40 Fur Accessories Gold Coast of Queensland, Australia. 41 Keyrings We are proud of our heritage and 42 Oilskin Waxed Products will continue to work passionately to bring you quality products that 44 Hat Accessories are quintessentially Australian. 45 Scarves Established in 1969, the Jacaru brand reflects the spirit that is 46 Product Care Australia - wild, untameable, strong and courageous. 47 Size Chart Jacaru - Handcrafted in Australia. -

John Halperin Bloomsbury and Virginia W

John Halperin ., I Bloomsbury and Virginia WooH: Another VIew . i· "It had seemed to me ever since I was very young," Adrian Stephen wrote in The Dreadnought Hoax in 1936, "that anyone who took up an attitude of authority over anyone else was necessarily also someone who offered a leg to pull." 1 In 1910 Adrian and his sister Virginia and Duncan Grant and some of their friends dressed up as the Emperor of Abyssinia and his suite and perpetrated a hoax upon the Royal Navy. They wished to inspect the Navy's most modern vessel, they said; and the Naval officers on hand, completely fooled, took them on an elaborate tour of some top secret facilities aboard the HMS Dreadnought. When the "Dread nought Hoax," as it came to be called, was discovered, there were furious denunciations of the group in the press and even within the family, since some Stephen relations were Naval officers. One of them wrote to Adrian: "His Majesty's ships are not suitable objects for practical jokes." Adrian replied: "If everyone shared my feelings toward the great armed forces of the world, the world [might] be a happier place to live in . .. armies and suchlike bodies [present] legs that [are] almost irresistible." Earlier a similarly sartorial practical joke had been perpetrated by the same group upon the mayor of Cam bridge, but since he was a grocer rather than a Naval officer the Stephen family seemed unperturbed by this-which was not really a thumbing·of-the-nose at the Establishment. The Dreadnought Hoax was harder to forget. -

A Comparative Critical Study of Kate Roberts and Virginia Woolf

CULTURAL TRANSLATIONS: A COMPARATIVE CRITICAL STUDY OF KATE ROBERTS AND VIRGINIA WOOLF FRANCESCA RHYDDERCH A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF PhD UNIVERSITY OF WALES, ABERYSTWYTH 2000 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. 4" Signed....... (candidate) ................................................. z3... Zz1j0 Date x1i. .......... ......................................................................... STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed (candidate) ......... ' .................................................... ..... 3.. MRS Date X11.. U............................................................................. ............... , STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. hL" Signed............ (candidate) .............................................. 3Ü......................................................................... Date.?. ' CULTURAL TRANSLATIONS: A COMPARATIVE CRITICAL STUDY OF KATE ROBERTS AND VIRGINIA WOOLF FRANCESCA RHYDDERCH Abstract This thesis offers a comparative critical study of Virginia Woolf and her lesser known contemporary, the Welsh author Kate Roberts. To the majority of -

ALLAN ADAIR Or HERE and THERE in MANY LANDS

https://doi.org/10.24355/dbbs.084-202003181102-0 https://doi.org/10.24355/dbbs.084-202003181102-0 https://doi.org/10.24355/dbbs.084-202003181102-0 THE SEAL TOSSED ROR\' C.\IL\' FR ~I SII) I\ ' J() SIIH.. https://doi.org/10.24355/dbbs.084-202003181102-0 ALLAN ADAIR or HERE AND THERE IN MANY LANDS By DR. GORDON STABLES, R.N. A11thoreof::.' Dur Home in the S-ilver West,' 'In the Land of the Lion a1id the Ostrich,' etc., etc. WITH COLOURED AND OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS FOURTH IMPRESSION LONDON THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY 4 Bouverie Street and 65 St. Paul's Churchyard https://doi.org/10.24355/dbbs.084-202003181102-0 https://doi.org/10.24355/dbbs.084-202003181102-0 CONTENTS PAGB CIIAPTER I. 'THE CHILD IS FATHER TO THE MAN'. 5 II. B'i THE BANKS OF THE QUEENLY TAY 16 " III. TIIE HO~IE-COMING OF UNCLE JACK " . 27 IV. 'THIS IS THE HousE THAT JACK BUILT' " . 39 V. LIFE AT CASTLE !NDOLENCE " . 51 VI. ÜNLY THE \YAIL OF THE WI'.\'D 62 " VII. HE OPENED HIS EYES IN A STRANGE RooM • 73 " VIII. THE STOWAWAY 86 " IX. LIFE ON THE Goon SHIP LIVINGSTONE , " . 96 X. ADVENTURES AT THE CAPE • 107 " XI. MIDNIGHT ADVENTURE IN THE FOREST u8 " XII. THE SWORD•FISH AND THE WHALE 128 " XIII. A NEW HERO 1 " 39 XIV. IN A DEN OF RATTLERS • 151 " A https://doi.org/10.24355/dbbs.084-202003181102-0 2 CONTENTS CHAPTER XV. A Ho~m IN TIII; WII.PS XVI. 'IIANDS ur, l\lEN ! ' " XVII. WHERE DAYUGIIT Nl'.\'E:R Sl!IITS 1115 En:. -

Three-Deckers and Installment Novels: the Effect of Publishing Format Upon the Nineteenth- Century Novel

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1965 Three-Deckers and Installment Novels: the Effect of Publishing Format Upon the Nineteenth- Century Novel. James M. Keech Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Keech, James M. Jr, "Three-Deckers and Installment Novels: the Effect of Publishing Format Upon the Nineteenth-Century Novel." (1965). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1081. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1081 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been - microfilmed exactly as received 66-737 K E E C H , Jr., James M., 1933- THREE-DECKERS AND INSTALLMENT NOVELS: THE EFFECT OF PUBLISHING FORMAT UPON THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY NOVEL. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1965 Language and Literature, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THREE-DECKERS AMD INSTALLMENT NOVELS: THE EFFECT OF PUBLISHING FORMAT UPON THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY NOVEL A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulflllnent of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English hr James M. Keech, Jr. B.A., University of North Carolina, 1955 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1961 August, 1965 ACKNOWLEDGMENT I wish to express my deepest appreciation to the director of this study, Doctor John Hazard Wildman. -

The Mid-Twentieth-Century American Poetic Speaker in the Works of Robert Lowell, Frank O’Hara, and George Oppen

“THE OCCASION OF THESE RUSES”: THE MID-TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICAN POETIC SPEAKER IN THE WORKS OF ROBERT LOWELL, FRANK O’HARA, AND GEORGE OPPEN A dissertation submitted by Matthew C. Nelson In partial fulfillment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In English TUFTS UNIVERSITY May 2016 ADVISER: VIRGINIA JACKSON Abstract This dissertation argues for a new history of mid-twentieth-century American poetry shaped by the emergence of the figure of the poetic speaker as a default mode of reading. Now a central fiction of lyric reading, the figure of the poetic speaker developed gradually and unevenly over the course of the twentieth century. While the field of historical poetics draws attention to alternative, non-lyric modes of address, this dissertation examines how three poets writing in this period adapted the normative fiction of the poetic speaker in order to explore new modes of address. By choosing three mid-century poets who are rarely studied beside one another, this dissertation resists the aesthetic factionalism that structures most historical models of this period. My first chapter, “Robert Lowell’s Crisis of Reading: The Confessional Subject as the Culmination of the Romantic Tradition of Poetry,” examines the origins of M.L. Rosenthal’s phrase “confessional poetry” and analyzes how that the autobiographical effect of Robert Lowell’s poetry emerges from a strange, collage-like construction of multiple texts and non- autobiographical subjects. My second chapter reads Frank O’Hara’s poetry as a form of intentionally averted communication that treats the act of writing as a surrogate for the poet’s true object of desire. -

Ernest Hemingway Global American Modernist

Ernest Hemingway Global American Modernist Lisa Tyler Sinclair Community College, USA Iconic American modernist Ernest Hemingway spent his entire adult life in an interna- tional (although primarily English-speaking) modernist milieu interested in breaking with the traditions of the past and creating new art forms. Throughout his lifetime he traveled extensively, especially in France, Spain, Italy, Cuba, and what was then British East Africa (now Kenya and Tanzania), and wrote about all of these places: “For we have been there in the books and out of the books – and where we go, if we are any good, there you can go as we have been” (Hemingway 1935, 109). At the time of his death, he was a global celebrity recognized around the world. His writings were widely translated during his lifetime and are still taught in secondary schools and universities all over the globe. Ernest Hemingway was born 21 July 1899, in Oak Park, Illinois, also the home of Frank Lloyd Wright, one of the most famous modernist architects in the world. Hemingway could look across the street from his childhood home and see one of Wright’s innovative designs (Hays 2014, 54). As he was growing up, Hemingway and his family often traveled to nearby Chicago to visit the Field Museum of Natural History and the Chicago Opera House. Because of the 1871 fire that destroyed structures over more than three square miles of the city, a substantial part of Chicago had become a clean slate on which late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century architects could design what a modern city should look like. -

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan A Comprehensive Listing of the Vessels Built from Schooners to Steamers from 1810 to the Present Written and Compiled by: Matthew J. Weisman and Paula Shorf National Museum of the Great Lakes 1701 Front Street, Toledo, Ohio 43605 Welcome, The Great Lakes are not only the most important natural resource in the world, they represent thousands of years of history. The lakes have dramatically impacted the social, economic and political history of the North American continent. The National Museum of the Great Lakes tells the incredible story of our Great Lakes through over 300 genuine artifacts, a number of powerful audiovisual displays and 40 hands-on interactive exhibits including the Col. James M. Schoonmaker Museum Ship. The tales told here span hundreds of years, from the fur traders in the 1600s to the Underground Railroad operators in the 1800s, the rum runners in the 1900s, to the sailors on the thousand-footers sailing today. The theme of the Great Lakes as a Powerful Force runs through all of these stories and will create a lifelong interest in all who visit from 5 – 95 years old. Toledo and the surrounding area are full of early American History and great places to visit. The Battle of Fallen Timbers, the War of 1812, Fort Meigs and the early shipbuilding cities of Perrysburg and Maumee promise to please those who have an interest in local history. A visit to the world-class Toledo Art Museum, the fine dining along the river, with brew pubs and the world famous Tony Packo’s restaurant, will make for a great visit.